Norse mythology

|

|

Norse mythology, Viking mythology or Scandinavian mythology refer to the pre-Christian religion, beliefs and legends of the Scandinavian people, including those who settled on Iceland, where the written sources for Norse mythology were assembled. It is the best-known version of the older common Germanic mythology, which also includes the closely related Anglo-Saxon mythology. Germanic mythology, in its turn, had evolved from an earlier Indo-European mythology.

Norse mythology was a collection of beliefs and stories shared by North Germanic tribes, not a revealed religion, in the sense that there was no claim to a divinely inspired scripture. The mythology was transmitted orally during most of the Viking Age, and our knowledge about it is mainly based on the Eddas and other medieval texts written down after Christianisation.

In Scandinavian folklore, these beliefs held on the longest, and in rural areas some traditions have been maintained until today, recently being revived or reinvented as Ásatrú or Odinism. The mythology also remains as an inspiration in literature (see Norse mythological influences on later literature) as well as on stage productions and movies.

| Contents |

Sources

Most of this mythology was passed down orally, and much of it has been lost. However, some of it was captured and recorded by Christian scholars, particularly in the Eddas and the Heimskringla by Snorri Sturluson, who rejected the idea that pre-Christian deities were devils. There is also the Danish Gesta Danorum by Saxo Grammaticus, where, however, the Norse gods are strongly euhemerized.

The Prose or Younger Edda was written in the early 13th century. It may be thought of primarily as a handbook for aspiring poets, which lists and describes traditional tales which formed the basis of standardised poetic expressions, such as "kennings". We know the author of the Prose Edda to be Snorri Sturluson, the renowned Icelandic chieftain, poet and diplomat.

The Elder Edda (also known as the Poetic Edda) was written about 50 years later. It contains 29 long poems, of which 11 deal with the Germanic deities, the rest with legendary heroes like Sigurd the Volsung (the Siegfried of the German version Nibelungenlied). Although scholars think it was written down later than the other Edda, we know it as the Elder Edda because of the antiquity of the contents.

Besides these sources, there are surviving legends in Scandinavian folklore, and there are hundreds of place names in Scandinavia named after the gods. A few runic inscriptions, such as the Rök Runestone and the Kvinneby amulette, make references to the mythology. There are also several image stones that depict scenes from Norse mythology, such as Thor's fishing trip, scenes from the Völsunga saga, Odin and Sleipnir, Odin being devoured by Fenrir, and Hyrrokkin riding to Baldr's funeral. In Denmark, a stone has been found which depicts Loki with curled dandy-like mustaches and lips that are sewn together. There are also smaller images, such as figurines depicting the gods Odin (with one eye), Thor (with his hammer) and Freyr.

Cosmology

In Norse mythology, the earth was believed to be a flat disc. Asgard, where the gods lived, was located at the centre of the disc, and could only be reached by walking across the rainbow (the Bifrost bridge). The Giants lived in an equivalent abode called Jotunheim (giant-home). A cold, dark underground abode called Niflheim was ruled by the goddess Hel. This was the eventual dwelling-place of most of the dead. Located somewhere in the south was the fiery realm of Muspell, home of the fire giants. Further otherworldly realms include Álfheim, home of the light-elves (ljósalfar), Svartalfheim, home of the dark-elves, and Nidavellir, the mines of the dwarves. In between Asgard and Niflheim was Midgard, the world of men (see also Middle Earth).

Supernatural beings

There are three "clans" of deities, the Aesir, the Vanir, and the Iotnar (referred to as giants in this article). The distinction between Aesir and Vanir is relative, for the two are said to have made peace, exchanged hostages, intermarried and reigned together after a prolonged war, which the Aesir had finally won. Some gods belong in both camps. Some scholars have speculated that this tale symbolized the way the gods of invading Indo-European tribes supplanted older nature-deities of the aboriginal peoples, although it should be firmly noted that this is conjecture. Other authorities (compare Mircea Eliade and J.P. Mallory) consider the Aesir/Vanir division to be simply the Norse expression of a general Indo-European division of divinities, parallel to that of Olympians and Titans in Greek mythology, and in parts of the Mahabharata.

The Aesir and the Vanir are generally enemies with the Iotnar (singular Iotunn or Jotuns; Old English Eotenas or Entas). They are comparable to the Titans and Gigantes of Greek mythology and generally translated as "giants", although "trolls" and "demons" have been suggested as suitable alternatives. However, the Aesir are descendants of Iotnar and both Aesir and Vanir intermarry with them. Some of the giants are mentioned by name in the Eddas, and they seem to be representations of natural forces. There are two general types of giant: frost-giants and fire-giants. There were also elves and dwarfs, whose role is shadowy but who are generally thought to side with the gods.

In addition, there are many other supernatural beings: Fenris (or Fenrir) the gigantic wolf, and Jormungand the sea-serpent (or "worm") that is coiled around the world. These two monsters are described as the progeny of Loki, the trickster-god, and a giant. More benevolent creatures are Hugin and Munin (thought and memory), the two ravens who keep Odin, the chief god, apprised of what is happening on earth, and Ratatosk, the squirrel which scampers in the branches of the world ash, Yggdrasil, which is central to the conception of this world.

Along with many other polytheistic religions, this mythology lacks the good-evil dualism of the Middle Eastern tradition. Thus, Loki is not primarily an adversary of the gods, though he is often portrayed in the stories as the nemesis to the protagonist Thor, and the giants are not so much fundamentally evil, as rude, boisterous, and uncivilized. The dualism that exists is not evil vs good, but order vs chaos. The gods represent order and structure whereas the giants and the monsters represent chaos and disorder.

Völuspá: the origin and end of the world

The origin and eventual fate of the world are described in Völuspá ("The völva's prophecy" or "The sybil's prophecy"), one of the most striking poems in the Poetic Edda. These haunting verses contain one of the most vivid creation accounts in all of religious history and a representation of the eventual destruction of the world that is unique in its attention to detail.

In the Völuspá, Odin, the chief god of the Norse pantheon, has conjured up the spirit of a dead Völva (Shaman or sybil) and commanded this spirit to reveal the past and the future. She is reluctant: "What do you ask of me? Why tempt me?"; but since she is already dead, she shows no fear of Odin, and continually taunts him: "Well, would you know more?" But Odin insists: if he is to fulfil his function as king of the gods, he must possess all knowledge. Once the sybil has revealed the secrets of past and future, she falls back into oblivion: "I sink now".

The past

In the beginning there was the world of ice Niflheim and the world of fire Muspelheim, and between them was the Ginnungagap, a "grinning (or yawning) gap" in which nothing lived. In Ginnungagap, the fire and the ice met and the fire of Muspelheim licked the ice shaping a primordial giant Ymir and a giant cow, Audhumbla whose milk fed Ymir. The cow licked the ice created the first god Buri, who was the father of Bor, the father of the first Aesir Odin and his brothers Vili and Ve. Ymir was a hermaphrodite and procreated alone the race of giants. Then, Bor's sons Odin, Vili and Ve slaughtered Ymir and from his body they created the world.

The gods regulated the passage of the days and nights, as well as the seasons. The first human beings were Ask (ash) and Embla (elm), who were carved from wood and brought to life by the gods Odin, Honir/Vili and Lodur/Ve. Sol is the goddess of the sun, a daughter of Mundilfari, and wife of Glen. Every day, she rides through the sky on her chariot, pulled by two horses named Alsvid and Arvak. This passage is known as Alfrodull, meaning "glory of elves", which in turn was a common kenning for the sun. Sol is chased during the day by Skoll, a wolf that wants to devour her. Solar eclipses signify that Skoll has almost caught up to her. It is fated that Skoll will eventually catch Sol and eat her; however, she will be replaced by her daughter. Sol's brother, the moon, Mani, is chased by Hati, another wolf. The earth is protected from the full heat of the sun by Svalin, who stands between the earth and Sol. In Norse belief, the sun did not give light, which instead emanated from the manes of Alsvid and Arvak.

The sybil describes the great ash tree Yggdrasil and the three norns (female symbols of inexorable fate; their names, Urðr (Urd), Verðandi (Verdandi) and Skuld, indicate the past, present and future) who spin the threads of fate beneath it. She describes the primeval war between Aesir and Vanir and the murder of Baldr. Then she turns her attention to the future.

The future

Main article: Ragnarök.

The Old Norse vision of the future is remarkably bleak. In the end, it was believed, the forces of evil and chaos will outnumber and overcome the divine and human guardians of good and order. Loki and his monstrous children will burst their bonds; the dead will sail from Niflheim to attack the living. Heimdall, the watchman of the gods, will summon the heavenly host with a blast on his horn. Then will ensue a final battle between good and evil (Ragnarök), which the gods will lose, as is their fate. The gods, aware of this, will gather the finest warriors, the Einherjar, to fight on their side when the day comes, but in the end they will be powerless to prevent the world from descending into the chaos out of which it has once emerged; the gods and their world will be destroyed. Odin himself will be swallowed by Fenrir the wolf. Still, there will be a few survivors, both human and divine, who will populate a new world, to start the cycle anew. Or so the sybil tells us; scholars are divided on the question whether this is a later addition to the myth that betrays Christian influence.

Kings and Heroes

Sigurd.jpg

Sometimes the same hero resurfaces in several forms depending on which part of the Germanic world the epics survived such as Völund/Weyland and Siegfried/Sigurd, and probably Beowulf/Bödvar Bjarki. Other notable heroes are Hagbard, Starkad, Ragnar Lodbrok, Sigurd Ring, Ivar Vidfamne and Harald Hildetand. Notable are also the shieldmaidens who were "ordinary" women who had chosen the path of the warrior.

Germanic worship

Main article: Blót

Centres of faith

The Germanic tribes rarely or never had temples in a modern sense. The Blót, the form of worship practiced by the ancient Germanic and Scandinavian people resembled that of the Celts and Balts : it could occur in Sacred groves. It could also take place at home and/or at a simple altar of piled stones known as a "horgr". However, there seems to have been a few more important centres, such as Skiringsal, Lejre and Uppsala. Adam of Bremen claims that there was a temple in Uppsala (see Temple at Uppsala) with three wooden statues of Thor, Odin and Freyr.

Priests

While a kind of priesthood seems to have existed, it never took on the professional and semi-hereditary character of the Celtic druidical class. This was because the shamanistic tradition was maintained by women, the Völvas. It is often said that the Germanic kingship evolved out of a priestly office. This priestly role of the king was in line with the general role of godi, who was the head of a kindred group of families (for this social structure, see norse clans), and who administered the sacrifices.

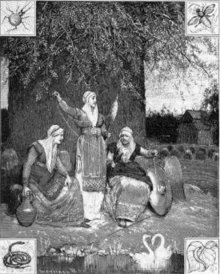

Midvinterblot.jpg

Human sacrifice

A unique eye-witness account of Germanic human sacrifice survives in Ibn Fadlan's account of a Rus ship burial, where a slave-girl had volunteered to accompany her lord to the next world. More indirect accounts are given by Tacitus, Saxo Grammaticus and Adam von Bremen. The Heimskringla tells of Swedish King Aun who sacrificed nine of his sons in an effort to prolong his life until his subjects stopped him from killing his last son Egil. According to Adam of Bremen the Swedish kings sacrificed male slaves every ninth year during the Yule sacrifices at the Temple at Uppsala. The Swedes had the right not only to elect kings but also to depose them, and both king Domalde and king Olof Trätälja are said to have been sacrificed after years of famine. Odin was associated with death by hanging, and a possible practice of Odinic sacrifice by strangling has some archeological support in the existence of bodies perfectly preserved by the acid of the Jutland (later taken over by Danish people) peatbogs, into which they were cast after having been strangled. An example is Tollund Man. However, we possess no written accounts that explicitly interpret the cause of these stranglings, which could obviously have other explanations.

Interactions with Christianity

Ansgar.jpg

An important problem in interpreting this mythology is that often the closest accounts that we have to "pre-contact" times were written by Christians. As a case in point, the Younger Edda and the Heimskringla were written by Snorri Sturluson in the 13th century, over two hundred years after Iceland became Christianized around 1000 AD, at a time of a rather intense anti-pagan political climate in Scandinavia.

Virtually all of the saga literature came out of Iceland, a relatively small and remote island, and even in the climate of religious tolerance there, Sturluson was guided by an essentially Christian viewpoint. The Heimskringla, copies of which are as widespread in today's Norway as the Bible, provides some interesting insights into this issue. Snorri Sturluson introduces Odin as a mortal warlord in Asia who acquires magical powers, settles in Sweden, and becomes a demi-god following his death. Having undercut Odin's divinity, Sturluson then provides the story of a pact of Swedish King Aun with Odin to prolong his life by sacrificing his sons. Later in the Heimskringla, Sturluson records in detail how converts to Christianity such as Saint Olaf Haroldsson brutally convert Scandinavians to Christianity.

Sejdmen.jpg

In Iceland, trying to avert civil war, the Icelandic parliament voted in Christianity, but tolerated heathenry in the privacy of one's home. Hence the more tolerant atmosphere that allowed the development of saga literature, which has been a vital window to help us better understand the heathen era. See also Germanic Christianity.

Sweden, on the other hand, had a series of civil wars in the 11th century, which ended with the burning of the Temple at Uppsala.

The conversion did not happen overnight as the new faith was imposed more or less by force. The clergy did their utmost to teach the populace that the Norse gods were demons, but their success was limited and the gods never became evil in the popular mind.

Two centrally located and far from isolated settlements can illustrate how long the christianization took. Archaeological studies of graves at the Swedish island of Lovön have shown that the Christianisation took 150-200 years, and this was a location close to the kings and bishops.

Likewise in the bustling trading town of Bergen, two runic inscriptions have been found from the 13th century, where one says may Thor receive you, may Odin own you. A second one is a galdra which says I carve curing runes, I carve salvaging runes, once against the elves, twice against the trolls, thrice against the thurs. The second one also mentions the dangerous Valkyrie Skögul.

Otherwise there are few accounts from the 14th to the 18th century, but the clergy, such as Olaus Magnus (1555) wrote about the difficulties of extinguishing the old beliefs. Þrymskviða appears to have been an unusually resilient song, like the romantic Hagbard and Signy, and versions of both were recorded in the 17th century and as late as the 19th century. In the 19th and early 20th century Swedish folklorists documented what commoners believed, and what surfaced were many surviving traditions of the gods of Norse mythology. However, the traditions were by then far from the cohesive system of Snorri's accounts. Most gods had been forgotten and only the hunting Odin and the giant-slaying Thor figure in numerous legends. Freya is mentioned a few times and Baldr only survives in legends about place names.

Other elements of Norse mythology survived without being perceived as such, especially concerning supernatural beings in Scandinavian folklore. Moreover, the Norse belief in destiny has been very firm until modern times. Since the Christian hell resembled the abode of the dead in Norse mythology one of the names was borrowed from the old faith, Helvite i.e. Hel's punishement. Some elements of the Yule traditions were preserved, such as the Swedish tradition of slaughtering the pig at Christmas (see Christmas ham), which originally was part of the sacrifice to Frey.

Modern influences

| Day | Origin |

|---|---|

| Monday | Moon's day |

| Tuesday | Tyr's (Tiw's) day |

| Wednesday | Odin's (Woden's) day |

| Thursday | Thor's day |

| Friday | Frigg's or Freya's day |

| Sunday | Sun's day |

The Germanic gods have left traces in modern vocabulary. An example of this is some of the names of the days of the week: modelled after the names of the days of the week in Latin (named after Sun, Moon, Mars, Mercury, Jupiter, Venus, Saturn), the names for Tuesday through to Friday were replaced with Germanic equivalents of the Roman gods. In English, Saturn was not replaced, while Saturday is named after the sabbath in German, and is called "washing day" in Scandinavia.

Norse mythology also influenced Richard Wagner's use of literary themes from it to compose the four operas that comprise Der Ring des Nibelungen (The Ring of the Nibelung).

In the Marvel Universe, the Norse Pantheon and related elements play a prominent part, especially Thor who has been one of the longest running superheroes for the company. The Norse Pantheon heroes are also the main characters of Japanese anime Matantei Loki Ragnarok.

More recent have been attempts in both Europe and the United States to revive the old pagan religion under the name Ásatrú or Heathenry. In Iceland Ásatrú was recognized by the state as an official religion in 1973, which legalized its marriage, child-naming and other ceremonies. It is also an official and legal religion in Denmark and Norway, though it is still fairly new.

The Creatures series of computer games also borrows several names from Norse mythology. The most prominent are the three kinds of creatures you can raise, the Norns, Grendels and Ettins.

Fantasy Fiction Influence

Tales of great warriors and deadly mages gave rise to the fantasy genre in the 20th century.

Robert E. Howard borrowed extensively from Norse mythology in his many outstanding fantasy works, his best known creation being Conan the Barbarian, a fictional Cimmerian mercenary and the hero of numerous short stories and a novel. Later on others followed in his footsteps like J. R. R. Tolkien in his outstanding fantasy works The Lord of the Rings, The Silmarillion. After the Howard and Tolkien work was published, other authors were bound to follow. Many of the most famous authors like Robert Jordan, Terry Brooks, Raymond Feist, David Eddings, Tad Williams and others fantasy authors borrow heavily from the Norse mythology.

This helped the fantasy develop as a separate genre. And on the other hand, the birth of fantasy gave breath to role playing and computer games. Some RPGs like Dungeons and Dragons or Dragonlance are based on authors work (including Howard and Tolkien) and many mythologies (including the Norse mythology).

See also

Spelling of names in Norse mythology often varies depending on the nationality of the source material. In the articles presented here, several common forms of the names will be presented. For more information see Old Norse orthography.

External links

- Norse-Myths.com - Norse Mythology (http://www.norse-myths.com)

Dedicated to Norse mythology. Detailed re-tellings of the old Norse sagas.

- A collection of most of the standard texts (http://www.northvegr.org/lore/main.php) in (generally) comprehensible English translation

- Norse dieties and more (http://www.goetter-portal.de) (germ.)

- More source materials (http://www.sacred-texts.com/neu/index.htm)

- Timeless Myths - Norse Mythology (http://www.timelessmyths.com/norse) Information and tales from Norse and Germanic literatures

- Jörmungrund: Skálda- & vísnatal Norrœns Miðaldkveðskapar [Index of Old Norse/Icelandic Skaldic Poetry] (http://www.hi.is/~eybjorn/ugm/skindex/skindex.html) (In Icelandic.)

- Project Runeberg, a Nordic equivalent to Project Gutenberg

- CyberSamurai Encyclopedia - an encyclopedia about norse gods, goddesses, heroes and mythological creatures (http://www.cybersamurai.net/Mythology/NorseMyth.htm)

Bibliography (including some external links)

- Primary Sources

- Edda, Snorri Sturluson

- Elder Edda, Saemund (also known as the Codex Regius)

- Modern retellings (often inventive)

- Armstrong, Fredrick and Puls, Dave (2004). It Came From Animatus (http://www.animatusstudio.com/dvd/icmain.html). Rochester, N.Y.: Animatus Studio. DVD UPC: 825346-49479-1. Includes The Derf The Viking Trilogy (http://www.animatusstudio.com/derf/index.html), a cartoon series featuring the Norse gods.

- Colum, Padraic (1920). The Children of Odin: A Book of Northern Myths, illustrated by Willy Pogány. New York, Macmillan. Reprinted 2004 by Aladdin, ISBN 0689868855.

- Sacred Texts: The Children of Odin (http://www.sacred-texts.com/neu/ice/coo/index.htm). (Illustrated.)

- Baldwin Project: The Children of Odin (http://www.mainlesson.com/display.php?author=colum&book=odin&story=_contents). (Partial.)

- Crossley-Holland, Kevin (1981). The Norse Myths. New York: Pantheon Books. ISBN 0394748468. Also released as The Penguin Book of Norse Myths: Gods of the Vikings. Harmondsworth: Penguin. ISBN 0140258698.

- Guerber, H. A. (1909). Myths of the Norsemen: From the Eddas and Sagas. London: George G. Harrap. Reprinted 1992, Mineola, N.Y.: Dover. ISBN 0486273482. (The scholarly veneer is deceptive. Material from primary sources, scholarly speculation, and secondary invention is indistinguishably mixed.)

- Keary, A & E (1909), The Heroes of Asgard. New York: Macmillan Company. Reprinted 1982 by Smithmark Pub. ISBN 0831744758. Reprinted 1979 by Pan Macmillan ISBN 0333078020.

- Baldwin Project: The Heroes of Asgard (http://www.mainlesson.com/display.php?author=keary&book=asgard&story=_contents)

- Mable, Hanilton Wright (1901). Norse Stories Retold from the Eddas. Mead and Company. Reprinted 1999, New York: Hippocrene Books. ISBN 0781807700.

- Baldwin Project: Norse Stories Retold from the Eddas (http://www.mainlesson.com/display.php?author=mabie&book=norse&story=_contents)

- Mackenzie, Donald A. (1912). Teutonic Myth and Legend. New York: W. H. Wise & Co. 1934. Reprinted 2003 by University Press of the Pacific. ISBN 1410207404.

- Sacred Texts: Teutonic Myth and Legend (http://www.sacred-texts.com/neu/tml/index.htm).

- Munch, Peter Andreas (1927). Norse Mythology: Legends of Gods and Heroes, Scandinavian Classics. Trans. Sigurd Bernhard Hustvedt (1963). New York: American-Scandinavian Foundation. ISBN 0404045383.

- General secondary works

- Branston, Brian (1980). Gods of the North. London: Thames and Hudson. (Revised from an earlier hardback edition of 1955). ISBN 0500271771.

- Davidson, H. R. Ellis (1964). Gods and Myths of Northern Europe. Baltimore: Penguin. New edition 1990 by Penguin Books. ISBN 0140136274. (Several rune stones)

- —————— (1969). Scandinavian Mythology. London and New York: Hamlyn. ISBN 0872260410. Reissued 1996 as Viking and Norse Mythology. New York: Barnes and Noble.

- Dumézil, Georges (1973). Gods of the Ancient Northmen. Ed. & trans. Einar Haugen. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0520035070.

- Grimm, Jacob (1888). Teutonic Mythology, 4 vols. Trans. S. Stallybras. London. Reprinted 2003 by Kessinger. ISBN 0766177424, ISBN 0766177432, ISBN 0766177440, ISBN 0766177459. Reprinted 2004 Dover Publications. ISBN 0486436152 (4 vols.), ISBN 0486435466, ISBN 0486435474, ISBN 0486435482, ISBN 0486435490.

- Northvegr: Grimm's Teutonic Mythology (http://www.northvegr.org/lore/grimmst/index.php)

- Lindow, John (1988). Scandinavian Mythology: An Annotated Bibliography, Garland Folklore Bibliographies, 13. New York: Garland. ISBN 0824091736.

- —————— (2001). Norse Mythology: A Guide to the Gods, Heroes, Rituals, and Beliefs. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195153820. (A dictionary of Norse mythology.)

- Orchard, Andy (1997). Cassell's Dictionary of Norse Myth and Legend. London: Cassell. ISBN 0304363855.

- Page, R. I. (1990). Norse Myths (The Legendary Past). London: British Museum; and Austin: University of Texas Press. ISBN 0292755465.

- Rydberg, Viktor (1889). Teutonic Mythology, trans. Rasmus B. Anderson. London: Swan Sonnenschein & Co. Reprinted 2001, Elibron Classics. ISBN 1402193912. Reprinted 2004, Kessinger Publishing Company. ISBN 0766188914. (Rydberg's theories are generally not accepted.)

- Northvegr: Rydberg's Teutonic Mythology (http://www.northvegr.org/lore/rydberg/index.php) (Displayed by pages.)

- Boudicca's Bard: Teutonic Mythology (http://www.boudicca.de/teut.htm) (Entire work on a single page.)

- Simek, Rudolf (1993). Dictionary of Northern Mythology. Trans. Angela Hall. Cambridge: D. S. Brewer. ISBN 0859913694. New edition 2000, ISBN 0859915131.

- Simrock, Karl Joseph (1853–1855) Handbuch der deutschen Mythologie.

- Turville-Petre, E. O. Gabriel. (1964). Myth and Religion of the North: The Religion of Ancient Scandinavia. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. Reprinted 1975, Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0837174201.

- Vries, Jan de. Altgermanische Religionsgeschichte, 2 vols., 2nd. ed., Grundriss der germanischen Philogie, 12–13. Berlin: W. de Gruyter. (Generally considered the most authoritative current standard reference.)

da:Nordisk mytologi de:Germanische Mythologie el:Σκανδιναβική μυθολογία es:Mitología escandinava eo:Nord-ĝermana mitologio fr:Mythologie nordique fo:Ásatrúgv he:מיתולוגיה נורדית it:Mitologia nordica ko:북유럽 신화 la:Religio Germanica lv:Skandināvu mitoloģija ms:Mitos Norse nl:Noorse mythologie is:Norræn goðafræði ja:北欧神話 no:Norrøn mytologi pl:Mitologia nordycka pt:Mitologia nórdica ro:Mitologie nordică sl:Nordijska mitologija sv:Nordisk mytologi zh:北欧神话