History of the Philippines

|

|

| Contents |

Prehistoric Times

Main Article: Pre-colonial Philippines

Various Austronesian groups settled in what is now the Philippine islands by traversing land bridges coming from Taiwan and Borneo by 200,000 BCE (late Pleistocene). The Cagayan valley of northern Luzon contains large stone tools as evidence for the hominid hunters of the big game of the time: the elephant-like stegodon, rhinoceros, crocodile, tortoise, pig and deer. The Tabon caves of Palawan indicate settlement for at least 30,500 years; these hunter-gatherers used stone flake tools. (In Mindanao, the existence and importance of these prehistoric tools was noted by famed José Rizal himself, because of his acquaintance with Spanish and German scientific archaeologists in the 1880s, while in Europe.)

After the last ice age, the sea level rose an estimated 35m (110 feet), which cut the land bridges, filling the shallow seas north of Borneo. Thus the only method of migration left was the dugout prao, built by felling trees and hollowing them out with adzes. To this day, the Filipino word for village, barangay, is kin to the word for boat. Around 3000 BCE, Malays, from what is now Indonesia and Malaysia, also entered the area. Forty-five centuries later, one of these seafaring peoples would even play a part in the first circumnavigation of the globe in 1521.

The Sea-farers

The South China Sea has currents which run counterclockwise. Thus, during a southwest monsoon, from June through September, it is easy to sail from the western Philippines, north to South China. During a northeast monsoon, in December through February, sailing would be easy from South China to the coast of Vietnam. From Vietnam, Nusantao (Nusantara being the Malay and Indonesian term for the Malay archipelago) sailor-traders could travel east along latitudes 11 to 14 degrees to Palawan and Mindoro, in boats of shallow draft. 1

The areas of settlement were controlled by the supplies of fresh water; but since the land was bountiful, trade with other sea peoples provided for some interchange of beliefs and culture. (See: map of Southeast Asia)

Jar Burial

For example, the custom of Jar Burial, which ranges from Sri Lanka, to the Plain of Jars, in Laos, to Japan, also was practiced in the Tabon caves of Palawan. A spectacular example of a secondary burial jar is owned by the National Museum of the Philippines, a National Treasure, with a jar lid topped with two figures, one the deceased, arms crossed, hands touching the shoulders, the other a steersman, both seated in a prao, with only the mast missing from the piece. Secondary burial was practiced across all the islands of the Philippines during this period, with the bones reburied, some in the burial jars. Seventy-eight earthenware vessels were recovered from the Manunggul cave, Palawan, specifically for burial.

Trade items

One museum artifact, a ceremonial jade adze, almost 7 cm. long, of extremely fine workmanship, for such a fundamental tool, may indicate source for some of the wealth from the Philippines, since, in general, it is not known just what was traded by the sea-faring traders, except perhaps, jade and gold.

Thalassocracies

Since at least the 3rd century, the indigenous peoples were in contact with other East Asian nations. They were, to varying extents, under the Hindu-Malayan empires of Sumatra, Indochina, and Borneo and then, beginning with the Ming Dynasty, under the Chinese sphere of influence. A thalassocracy, or rule from the beaches prevailed.

In the earliest times, the items which were prized by the peoples included jars, which were a symbol of wealth throughout South Asia, and later metal, salt and tobacco. In exchange, the peoples would trade feathers, rhino horn, hornbill beaks, beeswax, birds nests, resin, rattan.2

Historic Times: Monday April 21 900

In 1989, the National Museum acquired the Laguna Copperplate Inscription, found in the Laguna de Bay of Manila, dated Monday April 21 900 (equivalent to the date Saka Era 822). The script is Javanese Kavi, which is derived from Brahmi. The Siyaka or Saka Era began on the vernal equinox of the year 78 CE, based on Indic jyotisa, or astronomy. The document is not Javanese, but the influence is, because Balitung, the king of Java at that time, is not mentioned, although the date is based on that civilization. The inscription forgives the descendants of Namwaran from a debt of 926.4 grams of gold, and is granted by the chief of Tondo (an area in Manila) and the authorities of Paila, Binwangan and Pulilan, which are all locations in Luzon. The words are a mixture of Sanskrit, Old Malay, Old Javanese and Old Tagalog.

One example of pre-Spanish Philippine script on a burial jar, derived from Brahmi survives, as most of the writing was done on perishable bamboo or leaves; an earthenware burial jar dated 1200s or 1300s with script was found in Batangas. This script is called in Tagalog Baybayin or Alibata.

Around 1405, the year that the war over succession ended in the Majapahit Empire, Sufi traders introduced Islam into the Hindu-Malayan empires and for about the next century the southern half of Luzon and the islands south of it were subject to the various Muslim sultanates of Borneo. During this period, the Japanese established a trading post at Aparri and maintained a loose sway over northern Luzon.

As later competing immigrant groups colonized the islands, settlers from earlier waves (Negritos and Igorots) were pushed back into the mountainous areas and proto-Malays became the dominant ethnic group. The modern Filipino lives in a culture that is a fascinating blend of Asian (Vedic,Theravada Buddhist, Hindu, Islamic), Spanish, Catholic, and American cultures that continues to both intrigue and baffle scholars today.

The New Spanish Colonial Period (1521–1821)

The Philippine Islands first came to the attention of Europeans when Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan landed there in 1521, claiming the lands for Spain. He was defeated by Lapu-Lapu, a native chieftain, at the Battle of Mactan, where he died. However, his ships reached the Spice Islands. The navigational charts of one of the ships, the Victoria, which circumnavigated the globe, were delivered to Seville 1522. In 1529, by the treaty of Zaragosa, Spain relinquished all claims to the Spice Islands (and westward) to Portugal. This treaty did not stop subsequent colonization. Until 1781, the Philippines were administered as a colony of New Spain (Mexico).

See also Limasawa Island

Subsequent expeditions expanded Mexican and Spanish influence in the islands. In 1543, Ruy López de Villalobos named the territory Las Islas Filipinas after Philip II of Spain. On April 27, 1565, the first permanent Spanish settlement was founded by Miguel López de Legaspi, with five Augustinian friars, and 400 armed men, on Cebu, which became the town of San Miguel. In 1570 the native city of Manila was conquered and declared a Spanish city the following year. When Legazpi decided to transfer his capital to Manila, Cebu receded into the backwaters as influence and power shifted north to Luzon and its wide expanse of fertile lands. The Spanish gradually took control of the islands, which became their outpost in Asia.

Spanish colonial rule brought Catholicism. One friar, Fr. Juan de Placencia wrote a Spanish-to-Tagalog Christian Doctrine 1593 which transliterated from Roman characters to Tagalog Baybayin characters; since most of the population of Manila could read and write Baybayin at one time, this effort probably helped the conversion to Christianity 3. Most of the islands, with the exception of Mindanao, which remained primarily Muslim, were converted. Muslims resisted the attempts of the Spanish to conquer the archipelago and this resulted in a lot of tension and violence which persists to the modern era.

The Universidad de Santo Tomas, the oldest educational institution, was opened in 1611.

The colonial period also saw the Spanish dominate the economy, focusing on the tobacco, as well as the Galleon Trade between Manila and Acapulco, Mexico. To avoid hostile powers, most trade between Spain and the Philippines was via the Pacific Ocean to Mexico (Manila to Acapulco), and then across the Caribbean Sea and Atlantic Ocean to Spain (Veracruz to Cádiz).

During Spain’s 333 years rule of the Philippines, there were more priests and missionaries rather than soldiers or civil servants in the country. The Spanish military had to fight off Chinese pirates (who sometimes came to lay siege to Manila), Dutch forces, Portuguese forces, and insurgent natives. In the late 16th century, the Japanese, under Hideyoshi, claimed control of the islands and for a time the Spanish paid tribute to secure their trading routes and protect Jesuit missionaries in Japan. In 1762, the British East India Company seized Manila with a force of 13 ships and 6830 men, easily taking the Spanish garrison of 600, but made little effort to extend their control beyond the port city. By 1764 the Treaty of Paris (1763) had returned Manila to Spain.

A Spanish province (1821–1898)

The Spanish Government took full control of the archipelago in 1821 when Mexico declared their independence.

Commerce was tightly controlled by Spanish authorities until 1837 when Manila was made an open port. In 1863, Queen Isabel II of Spain decreed the establishment of the public school system. Developments in and out of the country and the opening up of the Suez Canal in 1869, which helped cut travel time to Spain, brought new ideas to the Philippines. This prompted the rise of the illustrados, or the Filipino upper middle class. Many young Filipinos were thus able to study in Europe.

Gomburza and the Colonial Church

See also Separation of church and state in the Philippines

Although many Spanish friars protested abuses by the Spanish government and military they themselves have committed many abuses and had utilized the government for their own means. Many Filipinos were enraged when Friars blocked the ascent of highly trained Filipino clergy in the Catholic Church hierarchy. Vast lands were claimed as friar estates from landless farmers. There were also sexual abuses. 'Anak ni Padre Damaso'(Child of Father Damaso) has become a cliche to refer to an illegitimate child, especially that of a priest. The matyrdom of Fr. Jose Burgos, Fr. Zammora, and Fr. Gomez further aggravated mass discontent and is said to indirectly have ignited the Philippine revolution and had a profound effect on Dr. Jose Rizal. It was in the light of these abuses also that the Philippine Independent Church was born.

The Philippine Revolution (1896–1898)

Main article: Philippine Revolution

In the late 19th century there was increasing insurgency against Spain, as natives demanded independence. From the illustrados came a group of students who formed the Propaganda Movement. They did not wish separation from Spain, but did demand equality and political rights. They spoke out against the injustices of the colonial government and especially the Catholic friars. Among the propagandists were José Rizal, Marcelo H. del Pilar, and Graciano López Jaena. Rizal, the most famous of the propagandists, used the words of Christ to further the movement: touch me not (John 20: 13-17); he was executed on December 30, 1896. The propaganda movement created a unified Filipino identity overcoming lingustic and cultural differences across the diversified regions.

The injustices of the Spanish led to uprisings from the 1600s. The 1872 uprising, in Cavite, was notable since it had a large effect on the country. The Spanish put this down by executing three Filipino priests: Burgos, Gomez, and Zamora (see Gomburza). Historians generally agree that this execution marks the start of the Philippine Revolutionary Period.

In 1892 Andres Bonifacio founded a revolutionary society called the Katipunan. By 1896, Filipinos were openly rebelling against the Spanish and the revolution was spreading throughout the islands. The Filipinos succeeded in taking almost all Philippine territory, except for Manila.

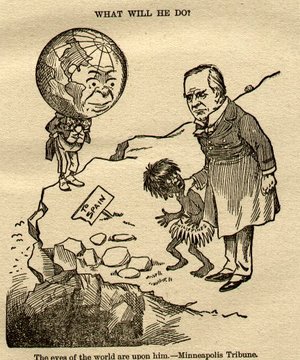

The U.S. Intervention

Little was known by the United States of the existence of the Philippine archipelago and it was not until Cuba appeared along the scene in 1895 which started the problems for the country. The Philippines , Puerto Rico and Guam were drag along with the conflicts of Independence, since these colonies also began to rebel at the same time. The U.S. at that time were an emerging nation and looking for way to compete as one of the world powers. Cuba's War of Independence with Spain was the perfect solution for the Americans. While the Americans wanted to help this people fight for independence, they also took a serious interest in occupying and controlling these colonies and making them their own.

On November 1897, William McKinley demanded that Cuba be granted independence and virtually "pressured" and abused Spain for the wrong doings. In January 25 1898, U.S. forces began arriving in Cuba and on February 15 the American battleship USS Maine exploded, killing 269. The Americans blamed the Spanish for the incident, when in fact it was later discovered to have been an accidental malfunction of the gas generators inside the battleship which caused the explosion. The Americans retaliated and went to war with the Spanish in Cuba and then on to the Philippines on May 1 in the same year where they fought both the Spaniards and Filipinos.

On May 1, 1898 the United States of America went to the Pacific and fought the Spaniards in the Spanish colony of the Philippines. (see: Spanish-American War). The U.S. Navy under Admiral George Dewey attacked the Spanish Navy by sea in Manila Bay while the Filipino forces led by General Emilio Aguinaldo allied with the U.S. who convinced the Filipinos, they were there to help them fight for independence, also attacked by land which resulted in a Spanish surrender.

Faced with inevitable defeat, Spain sued for peace—but instead of surrendering the Philippines to the Filipinos, the Spaniards was forced to sell the country to the United States at the Treaty of Paris in 1898 through "offers of money" by U.S. officials. Spain thus accepted the offer because they were in need of wealth due to the "problems" of Wars in Europe with Napoleon and the devastating loses of their colonies in Central America and South America who gained independence.

The Filipinos, under General Emilio Aguinaldo, declared victory and proclaimed their independence on June 12, 1898 in Cavite. Aguinaldo was voted by the Filipino people and became the first President of the Philippines. This act was opposed by the United States who had plans to take over the country.

The U.S. Period (1898–1935)

A civil government was established by the Americans in 1901 with William H. Taft as the first civil governor of the Philippines.

Filipinos were given greater participation in local governance and were appointed to several positions in government.

An elected Filipino legislature was inaugurated in 1907 and a bicameral congress, with a Senate and House of Representatives in 1916. Members to the elected legislature lost no time to lobby for immediate and complete independence from the United States. Several independence missions were sent.

At the end of the Spanish-American War, under the terms of the Treaty of Paris (1898), Spain ceded the Philippines to the United States in exchange for 20 million United States dollars. When it became clear to the Filipinos that American forces intended to occupy and control the country resulted in violent protests and revolts broke out.

Philippine - U.S. War (1899–1913)

Heated tensions between Filipinos and Americans began to mount rapidly when locals found that the U.S. were there to control and occupy the archipelago. On the night of February 4, 1899 a Filipino soldier was shot dead at gun point by a U.S. sniper at a U.S. military checkpoint, who was trying to cross the San Juan Bridge at San Juan del Monte in Manila.

Though Aguinaldo communicated for a ceasefire with the Americans, this was the incident that they were waiting for to take over the Philippines by force.

At a constitutional convention held against the wishes of American authorities, Aguinaldo was declared President of the Philippines Republic—and declared to be an "outlaw bandit" by the McKinley Administration.

The U.S. refused to recognize any Philippine right to self-government, and on February 4, 1899, Aguinaldo declared war against the United States for denying them independence. Some Americans accused the Filipino nationalists of Jacobinist tendencies, and US government officials repeatedly stated that few Filipinos were in favor of independence, although this conclusion was questioned by some. In the US, there was a movement to stop the war; some said that the US had no right to a land whose people wanted self-government; Andrew Carnegie, an industrialist and steel magnate, offered to buy the Philippines for 20 million United States dollars and give it to the Filipinos so that they could be free.

Although Americans have historically used the term the Philippine Insurrection, Filipinos and an increasing number of American historians refer to these hostilities as the Philippine-American War (1899–1913), and in 1999 the U.S. Library of Congress reclassified its references to use this term. In 1901, Aguinaldo was captured and swore allegiance to the United States. A large American military force was needed to occupy the country, and would be regularly engaged in war, against Filipino rebels, for another decade. An estimated 250,000 Filipinos were killed by the U.S. Forces in the attempt to put down the forces favoring independence.

Some measures of Filipino self-rule were allowed, however. The first legislative assembly was elected in 1907. A bicameral legislature, largely under Philippine control, was established. A civil service was formed and was gradually taken over by the Filipinos, who had effectively gained control by the end of World War I. The Catholic Church was disestablished, and a considerable amount of church land was purchased and redistributed.

The Commonwealth Era (1935–1946)

Main article: Commonwealth of the Philippines

When Woodrow Wilson became the American President, in 1913, there was a major change in official American policy concerning the Philippines. While the previous Republican administrations had envisioned the Philippines as a perpetual American colony, the Wilson administration decided to start a process that would gradually lead to Philippine independence. U.S. administration of the Philippines was declared to be temporary and aimed to develop institutions that would permit and encourage the eventual establishment of a free and democratic government. Therefore, U.S. officials concentrated on the creation of such practical supports for democratic government as public education and a sound legal system. The Philippines were granted free trade status, with the U.S. In 1916, the Philippine Autonomy Act, popularly known as the Jones Law, was passed by the U.S. Congress. The law which served as the new organic act (or constitution) for the Philippines, stated in its preamble that the eventual independence of the Philippines would be American policy, subject to the establishment of a stable government. The law maintained the Governor General of the Philippines, appointed by the President of the United States, but established a bicameral Philippine Legislature to replace the elected Philippine Assembly (lower house) and appointive Philippine Commission (upper house) previously in place. The Filipino House of Representatives would be purely elected while the new Philippine Senate would have the majority of its members elected by senatorial district with senators representing non-Christian areas appointed by the Governor-General. The 1920s saw alternating periods of cooperation and confrontation with American governors-general, depending on how intent the incumbent was on exercising his powers vis a vis the Philippine legislature.

In 1934, the United States Congress, having originally passed the Hare-Hawes-Cutting Act as a Philippine Independence Act over President Hoover's veto, only to have the law rejected by the Philippine legislature, finally passed a new Philippine Independence Act popularly known as the Tydings-McDuffie Act. The law provided for the granting of Philippine independence by 1946. The period 1935–1946 would ideally be devoted to the final adjustments required for a peaceful transition to full independence, a great latitude in autonomy being granted in the meantime. On May 14, 1935, an election to fill the newly created office of President of the Commonwealth of the Philippines was won by Manuel L. Quezon (Nacionalista Party) and a Filipino government was formed on the basis of principles superficially similar to the US Constitution. (See: Philippine National Assembly; see Signing_of_the_Philippine_Constitution for a picture of the signing.). The Commonwealth as established in 1935 featured a very strong executive, a unicameral National Assembly, and a Supreme Court composed entirely of Filipinos for the first time since 1901. The new government embarked on an ambitious agenda of establishing the basis for national defense, greater control over the economy, reforms in education, improvement of transport, the colonization of the island of Mindanao, and the promotion of local capital and industrialization. The Commonwealth however, was also faced with agrarian unrest, an uncertain diplomatic and military situation in South East Asia, and uncertainty about the level of United States commitment to the future Republic of the Philippines. In 1939-40, the Philippine Constitution was amended to restore a bicameral Congress, and permit the reelection of President Quezon, previously restricted to a single, six-year term.

The Japanese Occupation

A few hours after the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, the Japanese launched air raids in several cities and US military installations in the Philippines on December 8, and on December 10, the first Japanese troops landed in Northern Luzon.

General Douglas MacArthur, commander of the United States Armed Forces in the Far East (USAFFE), was forced to retreat to Bataan. Manila was occupied by the Japanese on January 2, 1942. The fall of Bataan was on April 9, 1942 with Corregidor Island, at the mouth of Manila Bay, surrendering on May 6 (an act which completely delayed the Japanese war timetable).

The Commonwealth government by then had exiled in Washington, DC upon the invitation of President Roosevelt. The Philippine Army continued to fight the Japanese in a guerilla war and were considered auxiliary units of the United States Army. Several Philippine military awards, such as the Philippine Defense Medal, Independence Medal, and Liberation Medal, were awarded to both the United States and Philippine Armed Forces.

The invasion by Japan began in December of 1941. As the Japanese forces advanced, Manila was declared an open city to prevent it from destruction, meanwhile, the government was moved to Corregidor. In March of 1942 U.S. General Douglas MacArthur and President Quezon fled the country. The cruelty of the Japanese military occupation of the Philippines is legendary. Guerilla units harassed the Japanese when they could, and on Luzon native resistance was strong enough that the Japanese never did get control of a large part of the island. Finally in October of 1944 McArthur had gathered enough additional troops and supplies to begin the retaking of the Philippines, landing with Sergio Osmena who had assumed the Presidency after Quezon's death. The battles entailed long fierce fighting; some of the Japanese continued to fight until the official surrender of the Empire of Japan on September 2, After their landing American forces undertook measures to suppress the Huk movement, which was originally founded to fight the Japanese Occupation. The American forces removed local Huk governments and imprisoned many high-ranking members of the Philippine Communist Party. While these incidents happened there was still fighting against the Japanese forces and despite the American measures against the Huk they still supported American soldiers in the fight against the Japanese.

Over a million Filipinos had been killed in the war, and many towns and cities, including Manila, were left in ruins. The final Japanese soldier to surrender was Hiroo Onoda, in 1974.

Independent Philippines and the Third Republic (1946–1972)

In April 1946 elections were held but despite the fact that the Democratic Alliance won the election they were not allowed to take their seats under the pretext that force had been used to manipulate the elections. The United States withdrew its sovereignty over the Philippines on July 4, 1946, as scheduled.

Manuel Roxas (Liberal Party) having been inaugurated president before the granting of independence strengthened political and economic ties with the United States—the controversial Philippine-US Trade Act, which allowed the US to partake equally in the exploitation of the countries natural resources—and rented sites for 23 military bases to the US for 99 years. These bases would later be used to launch operations in Korea, China, Vietnam and Indonesia.

During the Roxas administration a general amnesty was granted for those who had collaborated with the Japanese while at the same time the Huks were declared illegal. His administration ended prematurely when he died of heart attack April 15, 1948 while at the US Air Force Base in Pampanga.

Vice President Elpidio Quirino (Liberal Party, henceforth referred to as LP) was sworn in as president after the death of Roxas. He ran for election in 1949 against Jose P. Laurel (Nacionalista Party, henceforth referred to as NP) and won.

During this time the CIA under the leadership of Lt. Col. Edward G. Lansdale was engaged in paramilitary and psychological warfare operations with the goal to suppress the Huk-Movement. Among the measures which were undertaken were psyops-campaigns which exploited the superstition of many Filipinos and acts of violence by government soldiers which were disguised as Huks. Until 1950 the US had provided the Philippine military with supplies and equipment worth $200 million dollars.

Ramon Magsaysay was elected President in 1953. His campaign was massively supported by the CIA, both financially and through practical help in discrediting his political enemies.

The succeeding administrations of presidents Carlos P. Garcia (NP, 1957-61) and Diosdado Macapagal (LP, 1961-65) sought to expand Philippine ties to its Asian neighbors, implement domestic reform programs, and develop and diversify the economy.

Macapagal ran for reelection in 1965 but was defeated by former party-mate, Senate President Ferdinand Marcos who switched to the Nacionalista Party.

Marcos Era (1965–1986)

As president Ferdinand Marcos embarked on a massive spending in infrastructural development, such as roads, health centers and schools which gave the Philippines a taste of economic prosperity.

In 1969 Marcos sought and won an unprecedented second term in 1969 against Liberal Party Senator Sergio Osmeña, Jr. He was however unable to reduce massive government corruption or to instigate an economic growth proportional to the population growth. The Communist Party of the Philippines formed the New Peoples Army while the Moro National Liberation Front fought for an independent Mindanao. These events, together with student protests and labour strikes were later used as justification for the imposition of martial law.

Congress called for a Constitutional Convention in 1970 in response to public clamour for a new constitution to replace the colonial 1935 Constitution.

An explosion during the proclamation rally of the senatorial slate of the opposition Liberal Party in Plaza Miranda in Quiapo, Manila on August 21, 1971 prompted Marcos to suspend the writ of habeas corpus hours after the blast, which he restored on January 11, 1972 after public protests.

Using the rising wave of lawlessness and the threat of a Communist insurgency as justification, Marcos declared martial law on September 21, 1972 by virtue of Proclamation No. 1081. Marcos ruling by decree, curtailed press freedom and other civil liberties, closed down media establishments and Congress and ordered the arrest of opposition leaders and militant activists, including his staunchest critics Senator Benigno Aquino, Jr. and Senator Jose Diokno.

Constitutionally barred from seeking another term beyond 1973 and with his political enemies in jail, Marcos reconvened and maneuvered the proceedings of the Constitutional Convention to adopt a parliamentary form of government to pave the way for him to stay in power beyond 1973. Sensing that the constitution would be rejected in a nationwide plebiscite, Marcos decreed the creation of citizen's assemblies which anomalously ratified the constitution.

Even before the Constitution could be fully implemented, several amendments were introduced to it by Marcos which including the prolonging of martial law and permitting himself to be President and concurrent Prime Minister.

Rigged elections for an interim Batasang Pambansa (National Assembly) were held in 1978.

Bowing to pressure from the United States, Marcos called for snap presidential elections in 1986. The Batasang Pambansa (Parliament) went on to proclaim Marcos as the winner of the election.

Marcos governed from 1973 until mid-1981 in accordance with the transitory provisions of a new constitution that replaced the commonwealth constitution of 1935. He suppressed democratic institutions and restricted civil liberties during the martial law period, ruling largely by decree and popular referenda. The government began a process of political normalisation during 1978-81, culminating in the reelection of President Marcos to a 6-year term that would have ended in 1987. The Marcos government's respect for human rights remained low despite the end of martial law on January 17, 1981. His government retained its wide arrest and detention powers. Corruption and favouritism contributed to a serious decline in economic growth and development under Marcos.

In order to appease the Catholic Church before the visit of Pope John Paul II, Ferdinand Marcos officially lifted martial law on January 17, 1981, although retaining his strongman rule. An opposition boycotted presidential elections then ensued in June 1981, which pitted Marcos (Kilusang Bagong Lipunan) against retired Gen. Alejo Santos (Nacionalista Party). Marcos won by a margin of over 16 million votes, which constitutionally allowed him to have another six-year term.

The assassination of opposition leader Benigno "Ninoy" Aquino Jr. upon his return to the Philippines in 1983, after a long period of exile, coalesced popular dissatisfaction with Marcos and set in motion a succession of events that culminated in a snap presidential election in February 1986. The opposition united under Aquino's widow, Corazon Aquino, and Salvador Laurel, head of the United Nationalist Democratic Organization (UNIDO). The election was believed to be marred by widespread electoral fraud on the part of Marcos and his supporters. International observers, including a U.S. delegation led by Sen. Richard G. Lugar (R-Ind.), denounced the official results. Marcos was forced to flee the Philippines in the face of a peaceful civilian-military uprising (known as the People Power Revolution) that ousted him and installed Corazon Aquino as president on February 25, 1986. By that time the Philippines was a poorer country than before Marcos rise to power.

Restoration of Democracy and the Fifth Republic (1986 to present)

Corazon Aquino's assumption into power marked the restoration of democracy in the country. Aquino immediately formed a government to normalize the situation, provided for a transitional constitution which restored civil liberties and dismantled the heavily Marcos-ingrained bureaucracy—abolishing the Batasang Pambansa (parliament) and relieving all public officials.

The all Aquino-appointed 1986 Constitutional Commission submitted to the people a new Constitution which was overwhelmingly ratified on February 2, 1987 and went into effect on February 11 of the same year. The new constitution crippled presidential powers in declaring martial law, proposed the creation of autonomous regions in the Cordilleras and Muslim Mindanao, and restored the presidential form of government and the bicameral Congress.

Under Aquino's presidency progress was made in revitalizing democratic institutions and respect for civil liberties. However, the administration was also viewed by many as weak and fractious, and a return to full political stability and economic development was hampered by several attempted coups staged by disaffected members of the Philippine military.

Dormant for over 600 hundred years, Mount Pinatubo in Central Luzon erupted on June 1991—the second-largest volcanic eruption of the 20th century and cooled global weather by 1.5°C. It left more than 700 people dead and 200,000 homeless.

On September 16, 1991, despite the lobbying of President Aquino, the Senate rejected a new treaty that would have allowed a 10-year extension of the US military bases in the country. The United States turned over Clark Air Base in Pampanga to the government in November, and Subic Bay Naval Base in Zambales in December 1992, ending almost a century of military presence in the Philippines.

Aquino endorsed the candidacy of her Defense secretary Fidel V. Ramos (Lakas-NUCD) in the 1992 elections which he won by just 23.6% of the vote, over Miriam Defensor-Santiago (PRP), Eduardo Cojuangco, Jr. (NPC), House Speaker Ramon Mitra (LDP), former First Lady Imelda Marcos (KBL), Senate President Jovito Salonga (LP) and Vice President Salvador Laurel (NP).

Early in his administration, Ramos declared "national reconciliation" his highest priority. He legalized the communist party and created the National Unification Commission (NUC) to lay the groundwork for talks with communist insurgents, Muslim separatists, and military rebels. In June 1994, President Ramos signed into law a general conditional amnesty covering all rebel groups, as well as Philippine military and police personnel accused of crimes committed while fighting the insurgents. In October 1995, the government signed an agreement bringing the military insurgency to an end.

A standoff with China occurred in 1995, when the Chinese military built structures on Mischief Reef in the disputed Spratly Islands claimed by the Philippines as Kalayaan Islands.

A peace agreement with the Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF) under Nur Misuari, a major Muslim separatist group fighting for an independent Bangsamoro homeland in Mindanao, was signed in 1996, ending the 24-year old struggle. However an MNLF splinter group, the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) under Salamat Hashim continued the armed Muslim struggle for an Islamic state.

Wielding overwhelming mass support, former movie actor and Vice President Joseph Ejercito Estrada (PMP-LAMMP) won with close to 11 million votes, the 11-man race for the presidency in the 1998 elections. Estrada beat among others, his closest rival and administration candidate, House Speaker Jose De Venecia (Lakas-NUCD-UMDP) who got only 4.4 million, Senator Raul Roco (Aksyon Demokratiko), former Cebu governor Emilio Osmeña (PROMDI) and Manila Mayor Alfredo Lim (LP).

Under the cloud of the Asian financial crisis which began in 1997, Estrada's wayward governance exacted a heavy toll on the economy, unemployment worsened, the budget deficit ballooned, the currency plunged and the economy recovered much slower than its Asian neighbors. He waged an all-out war against the separatist Moro Islamic Liberation Front in Central Mindanao in late 1999 which displaced half a million people.

The bandit Abu Sayyaf Group abducted 21 hostages including 10 foreign tourists from the Sipadan Island resort in neighboring Sabah, Malaysia in March 2000 and held them hostage in Basilan, until freed in batches after over $20 million in ransom were reportedly paid by the Libyan government.

In October 2000, Ilocos Sur governor Luis "Chavit" Singson a close Estrada friend accused the President of receiving collections from jueteng—an illegal numbers game. On November 13, 2000 the House of Representatives impeached Estrada on grounds of bribery, graft and corruption, betrayal of public trust and culpable violation of the constitution. His impeachment trial in the Senate began on December 7 but broke down on January 17, after 11 senators allied with Estrada successfully blocked the opening of confidential bank records that would have been used by the House Prosecutors to incriminate the President. Shortly after the Senate blocked evidence against Estrada, thousands of people massed up at the EDSA Shrine, site of the People Power Revolution which ousted Marcos in 1986. Protesters at the EDSA Shrine rapidly swelled into the millions demanding for Estrada's immediate resignation. The en masse resignation of Estrada's cabinet and the withdrawal of support of the military and the police on January 19 signalled Estrada's lost of control of the government. The Supreme Court declared the presidency vacant on January 20, 2001 and swore in Vice President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo as the country's 14th President, while Estrada and his family evacuated the Malacañang Palace grounds.

Seeking to retain the presidential immunity from suit, Estrada challenged the legitimacy of Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo's government, claiming he did not resign from office and Arroyo was just an Acting President, but was dealt with a blow when the Supreme Court twice upheld its legitimacy.

On April 25, two weeks before the mid-term senatorial elections of May 2001, the Sandiganbayan—the Philippines' anti-graft court—issued a warrant arrest for the deposed president, which prompted his fanatic supporters to stage the so-called "EDSA Tres" or a third People Power Revolution at the EDSA Shrine which attempted to overthrow Arroyo's government on May 1.

In May 27, 2001 the Abu Sayyaf Group abducted anew 20 hostages including 3 Americans from the Dos Palmas resort in Palawan. The Abu Sayyaf executed one of its American hostages, other hostages were subsequently released after negotiations and ransom payments. The Abu Sayyaf was later neutralized when their leader Abu Sabaya was killed in an encounter off the coast of Sirawai, Zamboanga del Norte and the capture of Ghalib Andang (also known as Commander Robot) in Sulu on December 8, 2003.

Arroyo supported the US led Invasion of Iraq and sent a contingent of troops to Iraq. The troops were withdrawn in July 2004 as a condition for the release of a Filipino worker hostaged by Iraqi militants.

Complaining of high-level corruption in the military, a group of about 300 junior military officers staged a mutiny on July 27, 2003 occupying the Oakwood Premier in Ayala Center in Makati City and rigging the vicinity with bombs. The mutiny ended 22 hours later after the surrender of the mutineers.

Retracting several previous pronouncements, Arroyo (Lakas-CMD) ran in the May 10, 2004 elections against popular movie actor and Estrada buddy Fernando Poe, Jr. (KNP), Senator Panfilo Lacson (independent), her former Education Secretary Raul Roco (Aksyon Demokratiko) and evangelist Eduardo Villanueva (Bangon Pilipinas). After a lengthy canvassing in Congress, Arroyo was finally proclaimed the winner of the election on June 24 with over 1.1 million votes over her strongest contender Fernando Poe, Jr., her running-mate Senator Noli De Castro won the vice-presidency, and the administration party, the Lakas-CMD secured the majority in both houses of Congress.

During the span of 2004 and 2005, the Philippines has seen sporadic murders of government officials, government dissenters, opposition members, and journalists, among them Marlene Esperat and Klein Cantoneros. The Philippines has been ranked 1st in the List of Most Deadly Countries for Journalists in Non-War areas. Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo also spearheads the plan for a charter change on July 2006 that will transform the present presidential republic into a federal parliament. Opponents say that this is her plan to stay longer as a president. She has also been the current focus of the country, her husband and son being the alleged illegal gambling lords of the country. Her family has been implicated by a witness named Boy Mayor. She has also been the focus of 'destabilization plot' of the opposition in which a tape allegedly bearing her voice instructing election officials to increase the votes for her in Mindanao island.

See also

- Communications History of the Philippines

- Demographic History of the Philippines

- Military History of the Philippines

- Transportation History of the Philippines

References

• "Statistics: Spanish Language in the Philippines" (http://de.geocities.com/hispanofilipino/Articles/EstadisticasEng.html)

Notes

Note 1: William G. Solheim II, Avelina Legaspi, and Jaime S. Neri, S.J. Philippine National Museum – University of Hawaii archaeological survey in southeastern Mindanao. as cited in The People and Art of the Philippines, UCLA Museum of Cultural History, Los Angeles, California. Fall, 1981.

Note 2: Barbier 1988, Islands and Ancestors. Prestel, ISBN 3-7913-0899-8, Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Note 3: The Spanish friars were surprised at the ease with which the Filipinos could read Baybayin writing (right to left, left to right, and even upside down) apparently because the script was linear when incised on a bamboo stick, and was well suited to the language. However, the language would change in the face of pressure from Spanish words, consonants, and vowels.

External references

- 1493 to 1803 (http://www.fullbooks.com/The-Philippine-Islands-1493-18031.html)nl:Geschiedenis van de Filipijnen