Merthyr Tydfil

|

|

| Merthyr Tydfil county borough | |

|---|---|

| |

| Geography | |

| Area - Total - % Water | Ranked 21st 111 km² ? % |

| Admin HQ | Merthyr Tydfil |

| ISO 3166-2 | GB-MTY |

| ONS code | 00PH |

| Demographics | |

| Population - Total (April 29, 2001) - Density | Ranked 22nd 55,981 504 / km² |

| Ethnicity | 99.9% White |

| Welsh language - Any skills | Ranked 15th 17.7% |

| Politics | |

| Merthyr Tydfil County Borough Council http://www.merthyr.gov.uk/ | |

| Control | Labour |

| MP | Dai Havard |

| Contents |

Introduction

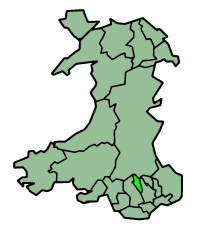

Merthyr Tydfil (Welsh: Merthyr Tudful) is a town and county borough in the traditional county of Glamorgan, south Wales, with a population of about 55,000.

Pre-History

Various peoples, migrants from Europe, had lived in the area for more than two thousand years, dating back to the Bronze age. The were followed from about 1000BCE by the Celts, and from their language, the Welsh language developed. Hillforts were built during the Iron Age and the tribes who lived in them were called Silures by the Roman invaders.

The Roman Invasion

The Romans had arrived in Wales by about 47-53CE and established a network of forts, with roads to link them. They had to fight hard to consolidate their conquests, and in 74 CE they built an auxiliary fortress at Penydarren, overlooking the River Taff (Taf). It covered an area of about 3 hectares, and formed part of the network of roads and fortifications. A road ran north-south through the area, linking the southern coast with mid-Wales via Brecon. Parts of this and other roads can still be traced and walked on.

The local tribe, known as the Silures, resisted this invasion fiercely from their mountain strongholds, but the Roman armies eventually prevailed. In time, relative peace was established.

The Roman empire eventually disintegrated, and the Penydarren fortress was abandoned by about 120CE. By 402 CE, the army in Britain comprised mostly Germanic troops and local recruits, and the cream of the army had been withdrawn across to the continent of Europe. By about 408CE, the armies of the Saxons were landing and the locals were left to their own devices to fight off the new invaders.

The coming of Christianity

The Latin language and some Roman customs and culture had become established, despite the withdrawal of the Roman army. The Christian religion was introduced, perhaps by monks who found their way up the valleys from Ireland and France.

Against this background, some petty kingdoms came slowly into existence. Welsh legend has it that a local chieftain arose, later to be known under the name of King Arthur. More legend than fact is known about him, but one story has it that he was a character named Ambrosius Aurelianus, a Romanised Briton. He probably spoke Latin and maintained some traces of Roman culture. He was possibly, at least nominally, a Christian, which had become the official religion of the Roman empire. He was enough of a military commander to band some of the tribes together and carve out a kingdom that included South Wales.

Tradition holds that a girl called Tydfil, a daughter of a local chieftain, Brychan, was an early local convert to Christianity, and was pursued by a band of marauding Picts and Saxons. They supposedly murdered or “martyred” her in about the year 480CE, and on the traditional site of her burial, a church was eventually built. From the death of Tydfil, Merthyr traditionally dates it’s foundation.

The Normans arrive

The valley through which the River Taff flowed was heavily wooded, with a few scattered farms on the mountain slopes, and this situation persisted for several hundred years. The Norman Barons moved in, after conquering England, but by 1093, they only occupied the lowlands and the uplands remained in the hands of the Welsh rulers. The effect on the locals was probably minimal. There were conflicts between the Barons and the families descended from the Welsh princes, and control of the land see-sawed to and fro. No permanent settlement was formed until well into the Middle Ages. People continued to be self-sufficient, living by farming and later by trading. In 1754, it was recorded that the valley was almost entirely populated by shepherds, and the markets and fairs at which farm produce were traded were many, bringing prosperity to some.

The Industrial Revolution

Merthyr was situated close to reserves of iron ore, coal, limestone and water, making it an ideal site for ironworks. In the wake of the Industrial revolution, it expanded rapidly.

Small-scale iron working and coal mining had been carried out at some places in South Wales since the Tudor period, but the first significant iron works were set up in 1759 by what became the Dowlais Iron Company.

In 1767, John Guest, an experienced iron worker, arrived from Shropshire to manage the works. He became a partner in the business, and by 1851 his grandson was the sole owner.

Several other iron works were started, with associated iron ore and coal mining. Merthyr expanded from a hamlet of some 700 inhabitants to about 80,000.

The demand for iron was fuelled by the railways and by the Royal Navy, who needed cannon for their ships. In 1802, Admiral Lord Nelson visited Merthyr to witness cannon being made.

Several railway companies established routes that linked Merthyr with coastal ports or other parts of Britain. They included the Brecon and Merthyr Railway, Vale of Neath Railway, Taff Vale Railway and Great Western Railway. They often shared routes to enable access to coal mines and iron works through rugged country, which presented great enegineering challenges.

In 1804, the world’s first railway locomotive, developed by the Cornish engineer Richard Trevithick, pulled 10 tons of iron from Merthyr on the newly constructed tramway.

Of the several iron works, two, at Dowlais and Cyfarthfa, expanded to become the largest in the area. Soon they were reckoned to be the biggest in the world. 50,000 tons of rails left just one iron works in 1844 to enable expansion of railways across Russia to Siberia.

The companies were mainly owned by two dynasties, the Guest and Crawshay families. One of the famous members of the Guest family was Lady Charlotte Guest who translated the Mabinogion into English from its original Welsh. The families also supported the establishment of schools for their workers.

At its peak, the Dowlais Iron Company operated 18 blast furnaces and employed 7,300 people. By 1857, they had constructed the world's most powerful rolling mill.

The Merthyr Riots

The riots of 1831 were probably precipitated by the ruthless collection of debts, which caused great poverty and hardship amongst workers affected by lower wages when the iron trade was depressed.

There is still controversy over what actually happened and who was to blame. It was probably more of an armed rebellion than an isolated riot. The initiators of the unrest were most probably the skilled workers; men who were much prized by the owners and often on friendly social terms with them. They also valued their loyalty to the owners and looked aghast at the idea of forming trade unions to demand higher wages. But events overtook them, and the community was tipped into rebellion.

The owners took fright at the challenge to their authority, and called on the military for assistance. Soldiers were sent from the garrison at Brecon. They clashed with the rioters, and several on both sides were killed. Despite the hope that they could negotiate with the owners, the skilled workers lost control of the movement.

Some 7,000 to 10,000 workers marched under a red flag, which was later adopted internationally as the symbol of the working classes. For four days, they effectively controlled Merthyr.

Even with their numbers and captured weapons, they were unable to effectively oppose disciplined soldiers for very long, and several of the supposed leaders of the riots were arrested. Some were transported as convicts to the penal colonies of Australia. One of them, Richard Lewis, popularly known as Dick Penderyn, was hanged, creating the first local working-class martyr. The story, slightly fictionalised, of the Riots is told in the novel The Fire People, by author Alexander Cordell.

The first trade unions, which were illegal and savagely suppressed, were formed shortly after the riots.

Many families had had enough of the strife, and they left Wales to utilise their skills elsewhere. Numerous people set out by ship to America, where the steel works of Pittsburgh were booming. It only cost about five pounds to travel steerage.

The decline of coal and iron

The steel and coal industries began to decline after World War One, and by the 1930’s, they had all closed. In 1987, the iron foundry, all that remained of the former Dowlais iron works, closed, marking the end of 228 years continuous production on one site.

The fortunes of Merthyr revived during World War Two, as war-related industry was established in the area. Many refugees from Europe settled in the town.

Post-World War Two

Immediately following World War Two, several large companies set up in Merthyr. In October 1948, the American-owned Hoover company opened a large washing machine factory and depot in the village of Pentrebach, a few miles south of Merthyr Tydfil. The factory was purpose-built to manufacture the Hoover Electric Washing Machine, and at one point, Hoover was the largest employer in the borough.

Several other companies built factories, including an aviation components company, Teddington Aircraft Controls, which opened in 1946.

The Teddington factory closed in the early 1970's.

Local Government

The current borough boundaries date back to 1974, when the former county borough of Merthyr Tydfil expanded slightly to cover Vaynor in Glamorgan and Bedlinog in Breconshire, it becoming a local government district in the administrative county of Mid Glamorgan at the time. The district became a county borough again on April 1, 1996.

Sport and Culture

The football club, Merthyr Tydfil F.C. or 'The Martyrs' play in the Southern Football League.

Merthyr Tydfil hosted the National Eisteddfod in 1881 and 1901. It is twinned with Clichy-la-Garenne, France.

External links

- Merthyr Tydfil A.F.C (http://www.themartyrs.com/)

- Merthyr Tydfil College (http://www.merthyr.ac.uk/)

- Old Merthyr Tydfil (http://www.alangeorge.co.uk/)

References

A Brief History of Merthyr Tydfil, by Joseph Gross. The Starling Press. 1980

| United Kingdom | Wales | Principal areas of Wales |

|

|

Anglesey | Blaenau Gwent | Bridgend | Caerphilly | Cardiff | Carmarthenshire | Ceredigion | Conwy | Denbighshire | Flintshire | Gwynedd | Merthyr Tydfil | Monmouthshire | Neath Port Talbot | Newport | Pembrokeshire | Powys | Rhondda Cynon Taff | Swansea | Torfaen | Vale of Glamorgan | Wrexham |