History of the United States (1789-1849)

|

|

| This article is part of the U.S. History series. |

| Colonial America |

| 1776 – 1789 |

| 1789 – 1849 |

| 1849 – 1865 |

| 1865 – 1918 |

| 1918 – 1945 |

| 1945 – 1964 |

| 1964 – 1980 |

| 1980 – 1988 |

| 1988 – present |

| Edit this box (http://en.wikipedia.org/w/wiki.phtml?title=Template:Ushistory&action=edit) |

After the election of George Washington as the first President of the United States in 1789, Congress passed the first of many laws organizing the government, and adopted a bill of rights in the form of ten amendments to the new Constitution—the United States Bill of Rights.

| Contents |

Washington's administration

George Washington was elected as the first U.S. president under the new Constitution. Washington had been a renowned hero of the American Revolutionary War, commander of the Continental Army, and president of the Constitutional Convention, and perhaps the most popular figure in U.S. political history at the time. Proclaimed the "Father of the Country", he easily won the presidential election of 1789, running virtually unopposed. He received all of the electoral votes.

Under Washington's presidency, the first U.S. Census was taken in 1790, furfilling the requirements of Section II in Article One of the Constitution, which said that "[An] Enumeration shall be made within three Years after the first Meeting of the Congress of the United States, and within every subsequent Term of ten Years, in such Manner as they shall by Law direct." The Census determined the number and shape of congressional districts, which elected congressmen to the U.S. House of Representatives.

Congress also passed the Judiciary Act of 1789, which established the entire federal judiciary. At the time the Judiciary Act provided for a Supreme Court of six justices, three circuit courts, and 13 district courts. It also created the offices of U.S. Marshal, Deputy Marshal, and District Attorney. In addition, it established the Supreme Court as the mediator of all disputes between states and the federal government concerning conflicting state and federal laws.

The Whiskey Rebellion in 1794, when settlers in the Monongahela Valley of western Pennsylvania protested against a federal tax on liquor and distilled drinks, was the first serious test of the federal government. Washington ordered federal marshals to serve court orders requiring the tax protesters to appear in federal district court. By August 1794, the protests became dangerously close to outright rebellion and on August 7 several thousand armed settlers gathered near Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Washington then invoked the Militia Law of 1792 to summon the militias of several states. A force of 13,000 men was organized, roughly the size of the entire army in the Revolutionary War. Under the personal command of Washington, Hamilton, and Revolutionary War hero Henry "Lighthorse Harry" Lee, the army marched to Western Pennsylvania and quickly suppressed the revolt. Two leaders of the revolt were convicted of treason, but pardoned by Washington. This response marked the first time under the new Constitution that the federal government had used strong military force to exert authority over the nation's citizens. It also was the only time that a sitting President would personally command the military in the field. The whiskey tax was repealed in 1802, never having been collected with much success.

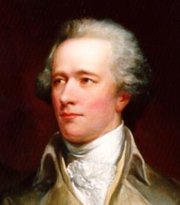

Many other major policies and decisions of Washington's two terms involved two of his cabinet members—Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton and Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson—whose different ideologies corresponded with the formation of the Federalist and Democratic-Republican parties, respectively. Although Washington warned against political parties in his farewell address, many felt that by the end of his term he was a Federalist. The Whiskey Rebellion seems to indicate this.

Despite a desire on the part of Washington to follow a policy of neutrality, the United States would grow to have a rich diplomatic history.

The Adams and Jefferson administrations

Washington retired in 1797, firmly declining to serve for more than eight years as the nation's head. His vice president, John Adams of Massachusetts, was elected the new president. Even before he entered the presidency, Adams had quarreled with Alexander Hamilton—and thus was handicapped by a divided party.

These domestic difficulties were compounded by international complications: France, angered by John Jay's recent treaty with Britain, used the British argument that food supplies, naval stores and war materiel bound for enemy ports were subject to seizure by the French navy. By 1797 France had seized 300 American ships and had broken off diplomatic relations with the United States. When Adams sent three other commissioners to Paris to negotiate, agents of Foreign Minister Charles Maurice de Talleyrand (whom Adams labeled "X, Y and Z" in his report to Congress) informed the Americans that negotiations could only begin if the United States loaned France $12 million and bribed officials of the French government. American hostility to France rose to an excited pitch. The so-called "XYZ Affair", led to the enlistment of troops and the strengthening of the fledgling U.S. Navy.

In 1799, after a series of naval battles with the French known as the Quasi-War, war seemed inevitable. In this crisis, Adams ignored Hamilton's advice to go to war and sent three new commissioners to France. Napoleon, who had just come to power, received them cordially, and the danger of conflict subsided with the negotiation of the Convention of 1800, which formally released the United States from its 1778 defense alliance with France. However, reflecting American weakness, France refused to pay $20 million in compensation for American ships taken by the French navy.

Hostility to France led Congress to pass the Alien and Sedition Acts, which had severe repercussions for American civil liberties. The Naturalization Act, which changed the requirement for citizenship from five to 14 years, was targeted at Irish and French immigrants suspected of supporting the Republicans. The Alien Act, operative for two years only, gave the president the power to expel or imprison aliens in time of war. The Sedition Act proscribed writing, speaking or publishing anything of "a false, scandalous and malicious" nature against the president or Congress. The few convictions won under the Sedition Act only created martyrs to the cause of civil liberties and aroused support for the Republicans.

The acts met with resistance. Jefferson and Madison sponsored the passage of the Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions by the legislatures of the two states in November and December 1798. According to the resolutions, states could "interpose" their views on federal actions and "nullify" them. The doctrine of nullification would be used later for the Southern states' defense of their interests vis-a-vis the North on the question of the tariff, and, more ominously, slavery.

Jeffersonian Democracy

Main article: Jeffersonian democracy

By 1800, Americans were ready for a change. Under Washington and Adams, the Federalists had established a strong government, but sometimes failing to honor the principle that the American government must be responsive to the will of the people, they had followed policies that alienated large groups. For example, in 1798 they had enacted a tax on houses, land and slaves, affecting every property owner in the country. Jefferson had steadily gathered behind him a great mass of small farmers, shopkeepers and other workers, and they asserted themselves in the election of 1800. Jefferson enjoyed extraordinary favor because of his appeal to American idealism. In his inaugural address, the first such speech in the new capital of Washington, DC, he promised "a wise and frugal government" to preserve order among the inhabitants but would "leave them otherwise free to regulate their own pursuits of industry, and improvement."

Jefferson's mere presence in The White House encouraged democratic procedures. He taught his subordinates to regard themselves merely as trustees of the people. He encouraged agriculture and westward expansion. Believing America to be a haven for the oppressed, he urged a liberal naturalization law. By the end of his second term, his far-sighted secretary of the treasury, Albert Gallatin, had reduced the national debt to less than $560 million. As a wave of Jeffersonian fervor swept the nation, state after state abolished property qualifications for the ballot and passed more humane laws for debtors and criminals.

Westward expansion and the War of 1812

Main article: War of 1812

The Louisiana Purchase in 1803 gave Western farmers use of the important Mississippi River waterway, removed the French presence from the western border of the United States, and provided U.S. settlers with vast potential for expansion.

A few weeks afterwards, war broke out between Britain and Napoleonic France. The United States, dependent on European revenues from the export of agricultural goods, tried to export food and raw materials to both warring great powers and to profit from transporting goods between their home markets and Caribbean colonies. Both sides permitted this trade when it benefited them, but opposed it when it did not.

Following the 1805 destruction of the French navy at the Battle of Trafalgar, Britain sought to impose a stranglehold over French overseas trade ties. Thus, in retaliation against U.S. trade practices, Britain imposed a loose blockade of the American coast.

Believing that Britain could not rely on other sources of food than the United States, Congress and President Jefferson suspended all U.S. trade with foreign nations in the Embargo Act of 1807, hoping to get the British to end their blockade of the American coast. The Embargo Act, however, devastated American agricultural exports and weakened American ports while Britain found other sources of food.

James Madison won the U.S. presidential election of 1808, largely on the strength of his abilities in foreign affairs at a time when Britain and France were both on the edge of war with the United States. He was quick to repeal the Embargo Act, refreshing American seaports.

In response to continued British interference with American shipping, and to British aid to American Indians in the Old Northwest, the Twelfth United States Congress—led by Southern and Western Jeffersonians—declared war on Britain in 1812. Westerners and Southerners were the most ardent supporters of the war, given their concerns about defending and expanding western settlements and to having access to world markets for their agricultural exports. New England Federalists opposed the war, and their reputation would suffer in the aftermath of the war, causing the party to fade away.

The United States came to a draw in the War of 1812 after bitter fighting, which lasted until January 8, 1815. The Treaty of Ghent officially ended the war. The Battle of New Orleans (which took place after the treaty was signed due to slow communication) was a victory for the United States and gave the country a psychological boost and propelled one of its commanders, Andrew Jackson, to political popularity.

The "Era of Good Feeling"

Domestically, the presidency of James Monroe (1817–1825) was termed the "Era of Good Feeling". In one sense, this term disguised a period of vigorous factional and regional conflict; on the other hand, the phrase acknowledged the political triumph of the Republican Party over the Federalist Party, which collapsed as a national force.

The decline of the Federalists brought disarray to the system of choosing presidents. At the time, state legislatures could nominate candidates. In presidential election of 1824 Tennessee and Pennsylvania chose Andrew Jackson, with South Carolina Senator John C. Calhoun as his running mate. Kentucky selected Speaker of the House Henry Clay; Massachusetts, Secretary of State John Quincy Adams; and a congressional caucus, Treasury Secretary William Crawford.

Monroe is probably best known for the Monroe Doctrine, which he delivered in his message to Congress on December 2, 1823. In it, he proclaimed the Americas should be free from future European colonization and free from European interference in sovereign countries' affairs. It further stated the United States' intention to stay neutral in wars between European powers and their colonies, but to consider any new colonies or interference with independent countries in the Americas as hostile acts towards the United States.

The return of factionalism and political parties

Personality and sectional allegiance played important roles in determining the outcome of the election. Adams won the electoral votes from New England and most of New York; Clay won Kentucky, Ohio and Missouri; Jackson won the Southeast, Illinois, Indiana, North and South Carolina, Pennsylvania, Maryland and New Jersey; and Crawford won Virginia, Georgia and Delaware. No candidate gained a majority in the Electoral College, so, according to the provisions of the Constitution, the election was thrown into the House of Representatives, where Clay was the most influential figure. In return for Clay's support, which essentially won him the presidency, Adams appointed Clay as his Secretary of State in what becomes known as The Corrupt Bargain.

During Adams's administration, new party alignments appeared. Adams's followers took the name of "National Republicans", later to be changed to "Whigs". Though he governed honestly and efficiently, Adams was not a popular president, and his administration was marked with frustrations. Adams failed in his effort to institute a national system of roads and canals. His years in office appeared to be one long campaign for reelection, and his coldly intellectual temperament did not win friends. Jackson, by contrast, had enormous popular appeal, especially among his followers in the newly named Democratic Party that emerged from the Republican Party, with its roots dating back to presidents Jefferson, Madison and Monroe. In the election of 1828, Jackson defeated Adams by an overwhelming electoral majority.

Jacksonian Democracy

Main article: Jacksonian democracy

Andrew Jackson drew his support from the small farmers of the West, and the workers, artisans and small merchants of the East, who sought to use their vote to resist the rising commercial and manufacturing interests associated with the Industrial Revolution.

The election of 1828 was a significant benchmark in the trend toward broader voter participation. Vermont had universal male suffrage from its entry into the Union and Tennessee permitted suffrage for the vast majority of taxpayers. New Jersey, Maryland and South Carolina all abolished property and tax-paying requirements between 1807 and 1810. States entering the Union after 1815 either had universal white male suffrage or a low taxpaying requirement. From 1815 to 1821, Connecticut, Massachusetts and New York abolished all property requirements. In 1824 members of the Electoral College were still selected by six state legislatures. By 1828 presidential electors were chosen by popular vote in every state but Delaware and South Carolina. Nothing dramatized this democratic sentiment more than the election of Andrew Jackson.

"The Trail of Tears"

Main article: Trail of Tears

In 1830 Congress passed the Indian Removal Act, which authorized the president to negotiate treaties that exchanged Indian tribal lands in the eastern states for lands west of the Mississippi River. In 1834 a special Indian territory was established in what is now Oklahoma. In all, Native American tribes signed 94 treaties during Jackson's two terms, ceding thousands of square kilometres to the federal government.

The Cherokees, whose lands in western North Carolina and Georgia had been guaranteed by treaty since 1791, faced expulsion from their territory when a faction of Cherokees signed a removal treaty in 1835. Despite protests from the elected Cherokee government and many white supporters, the Cherokees were forced to make the long and cruel trek to the Indian territory in 1838. Many died of disease and privation in what became known as the "Trail of Tears".

Battle of the Bank

Even before the nullification issue had been settled, another controversy occurred that challenged Jackson's leadership. It concerned the rechartering of the Second Bank of the United States. The First Bank of the United States had been established in 1791, under Alexander Hamilton's guidance, and had been chartered for a 20-year period. Though the government held some of its stock, it was not a government bank; rather, the bank was a private corporation with profits passing to its stockholders. It had been designed to stabilize the currency and stimulate trade; but it was resented by Westerners and working people who believed that it was a "monster" granting special favors to a few powerful men. When its charter expired in 1811, it was not renewed.

For the next few years, the banking business was in the hands of state-chartered banks, which issued currency in excessive amounts, creating great confusion and fueling inflation and concerns that state banks could not provide the country with a uniform currency. In 1816 a second Bank of the United States, similar to the first, was again chartered for 20 years.

From its inception, the second Bank was unpopular in the newer states and territories, and with less prosperous people everywhere. Opponents claimed the bank possessed a virtual monopoly over the country's credit and currency, and reiterated that it represented the interests of the wealthy few. Jackson, elected as a popular champion against it, vetoed a bill to recharter the bank. In his message to Congress, he denounced monopoly and special privilege, saying that "our rich men have not been content with equal protection and equal benefits, but have besought us to make them richer by act of Congress". The effort to override the veto failed.

In the election campaign that followed, the bank question caused a fundamental division between the merchant, manufacturing and financial interests (generally creditors who favored tight money and high interest rates), and the laboring and agrarian sectors, who were often in debt to banks and therefore favored an increased money supply and lower interest rates. The outcome was an enthusiastic endorsement of "Jacksonism". Jackson saw his reelection in 1832 as a popular mandate to crush the bank irrevocably—and found a ready-made weapon in a provision of the bank's charter authorizing removal of public funds.

In September 1833 Jackson ordered that no more government money be deposited in the bank, and that the money already in its custody be gradually withdrawn in the ordinary course of meeting the expenses of government. Carefully selected state banks, stringently restricted, were provided as a substitute. For the next generation the United States would get by on a relatively unregulated state banking system, which helped fuel westward expansion through cheap credit but kept the nation vulnerable to periodic panics. It was not until the Civil War that the United States chartered a national banking system.

Nullification Crisis

Cottonfieldpanorama.jpg

See the main article on the Nullification Crisis

Toward the end of his first term in office, Jackson was forced to confront the state of South Carolina on the issue of the protective tariff.

The protective tariff passed by Congress and signed into law by Jackson in 1832 was milder than that of 1828, but it further embittered many in the state. In response, a number of South Carolina citizens endorsed the "states' rights" principle of "nullification", which was enunciated by John C. Calhoun, Jackson's vice president until 1832, in his South Carolina Exposition and Protest (1828). South Carolina dealt with the tariff by adopting the Ordinance of Nullification, which declared both the tariffs of 1828 and 1832 null and void within state borders.

Nullification was only the most recent in a series of state challenges to the authority of the federal government. In response to South Carolina's threat, Jackson sent seven small naval vessels and a man-of-war to Charleston in November 1832. On December 10, he issued a resounding proclamation against the nullifiers. South Carolina, the president declared, stood on "the brink of insurrection and treason", and he appealed to the people of the state to reassert their allegiance to that Union for which their ancestors had fought.

Senator Henry Clay, though an advocate of protection and a political rival of Jackson, piloted a compromise measure through Congress. Clay's 1833 compromise tariff specified that all duties in excess of 20 percent of the value of the goods imported were to be reduced by easy stages, so that by 1842, the duties on all articles would reach the level of the moderate tariff of 1816. The rest of the South declared South Carolina's course unwise and unconstitutional. Eventually, South Carolina rescinded its action. Jackson had committed the federal government to the principle of Union supremacy. But South Carolina had obtained many of the demands it sought, and had demonstrated that a single state could force its will on Congress.

Westward expansion and the Mexican-American War

Main article: Mexican-American War

After Napoleon's defeat and the Congress of Vienna in 1815, an era of relative stability began in Europe. U.S. leaders paid less attention to European trade and conflict, and more to the internal development in North America. With the end of the wartime British alliance with Native Americans east of the Mississippi River, white settlers were determined to colonize indigenous lands beyond the Mississippi. In the 1830s the federal government forcibly deported the Southeastern tribes to less fertile territories to the west.

Westward expansion by official acts of the U.S. Government was accompanied by the western (and northern in the case of New England) movement of settlers on and beyond the frontier. Daniel Boone was one frontiersman who pioneered the settlement of Kentucky. This pattern was followed throughout the West as men traded with the Indians, and explored. Skilled fighters and hunters, these Mountain Men trapped beaver in small groups throughout the Rocky Mountains. After the demise of the Fur Trade, they established trading posts throughout the west, continuing trade with the Indians and serving the western migration of settlers to Utah, Oregon and California.

Americans did not question their right to colonize vast expanses of North America beyond their country's borders, especially into Oregon, California, and Texas. By the mid-1840s U.S. expansionism was articulated in terms of the ideology of "manifest destiny".

In May 1846 Congress declared war on Mexico. The U.S. defeated Mexico, unable to withstand the assault of the American artillery, short on resources, and plagued by a divided command. The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848 ceded Texas (with the Rio Grande boundary), California, and New Mexico to the United States. In the next thirteen years, the territories ceded by Mexico became the focal point of sectional tensions over the expansion of slavery.

Major events in the western movement of the U.S. population were the Homestead Act, a law by which, for a nominal price, a settler was given title to land to farm; the opening of the Northwest Territory to settlement; the Texas Revolution; the opening of the Oregon Trail; the Mormon Emigration to Utah in 1846–7; The California gold rush of 1849; the Colorado Gold Rush of 1859; and the completion of the US Transcontinental Railroad on May 10th, 1869.

| History of the United States: timeline & topics | Missing image Flag_of_the_United_States.png Flag of the United States | |

|---|---|---|

| ||