History of the United States (1865-1918)

|

|

| This article is part of the U.S. History series. |

| Colonial America |

| 1776 – 1789 |

| 1789 – 1849 |

| 1849 – 1865 |

| 1865 – 1918 |

| 1918 – 1945 |

| 1945 – 1964 |

| 1964 – 1980 |

| 1980 – 1988 |

| 1988 – present |

| Edit this box (http://en.wikipedia.org/w/wiki.phtml?title=Template:Ushistory&action=edit) |

At the end of the Civil War, the country was still bitterly divided. In the South, the Federal policy of Reconstruction continued for a decade before coming to an end, and many of the civil rights laws that were passed immediately after the end of the war were quickly abandoned. In the West, the country continued to expand, fueled by an unprecedented flood of new immigrants and leading to many conflicts with the native Sioux and Apache tribes, and the eventual displacement of much of the native population. U.S. industry expanded rapidly throughout the era; by the dawn of the 20th century, it was the dominant economic power and well on its way to taking its place among the imperial powers of the age. This economic boom was accompanied by the rise of populism and the American labor movement. Finally, the era was capped by U.S. involvement in World War I.

| Contents |

Reconstruction

Main article: Reconstruction

Reconstruction was the period after the American Civil War when the southern states of the defeated Confederacy, which had seceded from the United States, were reintegrated into the Union. The destructiveness of the Union invasion and defeat of the South, attacks on civilian targets and destruction of infrastructure, followed by exploitive economic policies in the defeated region after the war, caused lasting bitterness among Southerners toward the U.S. government. Abraham Lincoln had endorsed a lenient plan for reconstruction, but the immense human cost of the war and the social changes wrought by it led Congress to resist readmitting the rebel states without first imposing preconditions. A series of laws, passed by the Federal government, established the conditions and procedures for reintegrating the southern states.

Much of the impetus for Reconstruction involved the question of civil rights for the freed slaves in the southern states. In response to efforts by southern states to deny civil rights to the freed slaves, Congress enacted a civil rights act in 1866 (and again in 1875). This led to conflict with President Andrew Johnson, who vetoed the Civil Rights Act of 1866; however, his veto was overridden. This failure of the federal government to effectively reunite the country contributed to the government's failure for many decades to enforce the civil rights of the formerly enslaved African-Americans in the South.

After solid Republican gains in the midterm elections, the first Reconstruction Act was passed on March 2, 1867; the last on March 11, 1868. The first Reconstruction Act divided ten Confederate states (all except Tennessee, which had been readmitted in 1866) into 5 military districts. Governments that had been established under Abraham Lincoln's plan were abolished; the first Reconstruction Act stated that "no legal State governments or adequate protection for life or property now exist in the rebel States."

During the period of Reconstruction there was considerable upheaval in southern society. Northerners who moved south to participate in Southern governments; were called carpetbaggers by southerners, and were widely perceived as being motivated by graft and corruption, while locals who participated in these governments were called scalawags. Republicans took control of all state governorships and state legislatures, often installing blacks into positions of power. These events led to the formation of the original Ku Klux Klan, in 1866; but it lasted for only three years.

Three constitutional amendments were passed in the wake of the Civil War: the thirteenth, which abolished slavery; the fourteenth, which granted civil rights to African Americans; and the fifteenth, which extended the franchise to freed citizens. The fourteenth amendment was opposed by the southern states, and as a precondition of readmission to the Union, they were required to accept it (or the fifteenth after passage of the fourteenth).

The end of Reconstruction

All Southern states were readmitted by 1870, but Reconstruction continued until 1877, when the contentious Presidential election of 1876 was decided in favor of Rutherford B. Hayes, supported by Northern states, over his opponent, Samuel J. Tilden. Some historians have argued that the election was handed to Hayes in exchange for an end to Reconstruction; this theory characterizes the settlement of that election as the "Compromise of 1877". Not all historians agree with this theory; in any case, Reconstruction came to an end at this time.

The end of Reconstruction essentially marked the demise of the brief period of civil rights for African Americans. Within a few years after Reconstruction ended, the South created a segregated society, with whites and blacks going their own ways, and with whites in firm political control. The North allowed white supremacy and encouraged white ex-Confederates to regain their normal place as full citizens; in return the whites became reintegrated into the Union. Now that African Americans had gained their freedom at the cost of over 600,000 white deaths, there was little demand for further military intervention in the South. The initial flurry of civil rights measures were rapidly eroded. Much of the civil rights legislation was overturned by the United States Supreme Court near the end of the 19th Century. Most notably, the court ruled in the Civil Rights Cases 109 US 3 1883 that the fourteenth amendment, which established the personhood and citizenship of African-Americans, was now applicable to corporations, rather than African-Americans. A Southern-controlled Congress barred itself from preventing private businesses from segregating black and white citizens in public places, thus repealing the 1875 Civil Rights Act. Plessy v. Ferguson 163 US 537 1896 went even further, providing that state-mandated segregation was legal as long as it provided for "separate but equal" facilities. "Equal" was interpreted loosely, but this provision did ultimately provide an institutional basis for African-American political mobilization and organization in the mid-20th century.

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka 347 US 483 1954 was one of the landmark 20th-century cases in which the Supreme Court reversed itself on segregation. But it was not until the shock of the social movements of the mid-20th century that the Federal government formally struck down segregation in all public facilities; and In Title II of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 Plessy was formally reversed. This Act, along with the Voting Rights Act of 1965, finally paved the way to an end to officially-sanctioned racial segregation in the United States.

Further displacement of the indigenous population

Main article: Indian Wars

As in the East, expansion into the plains and mountains by miners, ranchers and settlers led to increasing conflicts with the indigenous population of the West. Many tribes — from the Utes of the Great Basin to the Nez Perces of Idaho — fought the whites at one time or another. But the Sioux of the Northern Plains and the Apache of the Southwest provided the most significant opposition to encroachment on tribal lands. Led by such resolute, militant leaders such as Red Cloud and Crazy Horse, the Sioux were skilled at high-speed mounted warfare. The Siousx were new arrivals on the Plains--previously they had been sedate farmers in the Great Lakes region. Once they learned to capture and ride horses they moved west, setroyed Indian tribes in their way, and became feared warriors. The Apaches built their economy from attacking, looting and kidnapping Hispanic farmers and other Indian tribes. They were equally adept and highly elusive, fighting in their environs of desert and canyons.

Conflicts with the Plains Indians continued through the Civil War. In 1876 the last serious Sioux war erupted, when the Dakota gold rush penetrated the Black Hills. The Army did not keep miners off Sioux hunting grounds. Yet, when ordered to take action against bands of Sioux hunting on the range according to their treaty rights, the Army moved vigorously.

In 1876, after several indecisive encounters, General George Custer found the main encampment of Sioux and their allies at the Battle of Little Big Horn. Custer and his men — who were separated from their main detachment — were all killed by the far more numerous Indians. Later, in 1890, a ghost dance ritual on the Northern Sioux reservation at Wounded Knee, South Dakota, led to an uprising that saw the Sioux attacking the Army, which responded with Gatling guns, killing hundreds. The Sioux settled down to a peaceful existence on the vast but povery-striken reservations.

Long before this, the means of subsistence and societies of the indigenous population of the Great Plains had been destroyed by the slaughter of the buffalo, almost driven to extinction in the decade after 1870 by indiscriminate hunting by both whites and Indians. Meanwhile, the Apaches' raids against villages in the Southwest continued until Geronimo, the last important chief, was captured in 1885.

U.S. federal government policy since the James Monroe administration had been to move the indigenous population beyond the reach of the white frontier. White "reformers" believed the indigenous population should be forcibly assimilated into white culture. The federal government even set up a school in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, in an attempt to impose the values and beliefs of the U.S. white population on indigenous youths.

In 1887 the Dawes Act reversed U.S. Indian policy, permitting the president to divide up tribal land and parcel out 0.65 km² of land to each head of a family. Such allotments were to be held in trust by the government for 25 years, after which time the owner won full title and citizenship. Lands not thus distributed, however, were offered for sale to settlers. This policy eventually resulted in the seizure and sale of almost half of the tribal lands. It also destroyed much of the communal organization of the tribes, further disrupting the traditional culture of the surviving indigenous population. In 1934 U.S. policy was reversed again by the Indian Reorganization Act, which attempted to protect tribal and communal life on the reservations. The Dawes act was an effort to integrate Indians into the mainstream; the majority accepted integration and were absorbed into American society, leaving as a trace the Indian ancestry of millions of families. Those who refused to assimilate remained on the reservations, supported by federal food, medicine and schooling.

Industrialization and Immigration

Industrialization

From 1865 to about 1900, the U.S. became the world's leading industrial nation, witnessing meteoric expansion in the pace and scale of production. The availability of land; the diversity of climate and the corollary economic diversity; the ample presence of navigable canals, rivers, and coastal waterways that filled the transportation needs of the emerging industrial economy; and the abundance of natural resources; fostered the cheap extraction of energy, fast transport, and the availability of capital that powered this Second Industrial Revolution.

Where the First Industrial Revolution shifted production from artisans to factories, the United States pioneered an expansion in organization, coordination, and scale of industries spurred on by technology and transportation. Railroads opened up vast markets, helping to explain steady growth in aggregate demand. The transcontinental railroad, built by Irish and Chinese immigrants, provided access to previously remote expanses of land. Railway construction boosted demand for capital resources, credit, and rapid increases in land values.

Meanwhile, technological advances in iron and steel making, like the Bessemer process and open-hearth furnace, combined with similar innovations in chemistry and other sciences to vastly improve the productivity and efficiency of industry. New communication tools, like the telegraph and telephone allowed actions to be coordinated across great distances. Innovations also occurred in how work was organized, as when Henry Ford developed the assembly line or Fredrick Taylor the formalized ideas of scientific management.

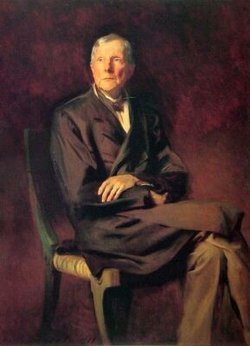

Industry learned how to coordinate such diversity of economic activities across broad geographic areas. To finance such large-scale enterprises, the corporation emerged as the dominant form of business organization. Corporations also grew by combining into trusts, creating single firms out of competing firms. Business leaders backed government policies of laissez-faire. High tariffs sheltered U.S. factories and workers from foreign competition (which hardly existed after 1880); federal railroad subsidies enriched investors, farmers and railroad workers, and created hundreds of towns and citirs; and all branches of government at all levels generally sought to stop organized labor from using violence to win strikes. Powerful industrialists, like Andrew Carnegie and John Rockefeller held great wealth and power; their employees were the best-paid in the world. In this context of cutthroat competition for accumulation, the skilled labor of the old-fashoned petty artisan and craftsman gave way to well-paid skilled workers and engineers as the nation deepened its technological base. Meanwhile, a steady stream of immigrants encouraged the availability of cheap labor, especially in the mining and manufacturing sectors.

Immigration

From 1840 to 1920 an unprecedented and diverse stream of immigrants came to the United States, approximately 37 million in total. They came from a variety of locations, 6 million from Germany, 4.5 million Irish, 4.75 million Italians, 4.2 million people from England, Scotland and Wales, 4.2 million from the Austro-Hungarian Empire, 2.3 million Scandinavians, and 3.3 million people from Russia (mostly Jews, Polish Catholics, and Lithuanian Catholics) entered the United States. Most came through the ports of New York City, but various ethnic groups settled in different locations. New York and the large cities of the East Coast were home to large Jewish, Irish, and Italian populations, while many Germans and Central Europeans moved to the Midwest, taking jobs in industry and mining.

Immigrants came for a variety of reasons, ranging from economic opportunities to the search for harvestable land to escaping from the Irish Potato Famine. Some Irish were recruited right off the boats into the Union Army during the Civil War. Many fled from religious or political persecution, especially conserrbative Lutherans from Saxony (Germany) and Jews from Russia and theAustro-Hyngarian Empire in the late 1800s. Even in the United States these new immigrants were subject to discrimination, however, and to the dangerous and exploitative labor conditions prevalent throughout much of the United States.

Agrarian Distress, Populism, and Organized Labor

Farmers and the Rise of Populism

Despite their remarkable progress, 19th-century U.S. farmers experienced recurring periods of hardship. Several basic factors were involved -- soil exhaustion, the vagaries of nature, a decline in self-sufficiency, and the lack of adequate legislative protection and aid. Perhaps most important, however, was over-production.

Along with the mechanical improvements which greatly increased yield per unit area, the amount of land under cultivation grew rapidly throughout the second half of the century, as the railroads and the gradual displacement of the Plains Indians opened up new areas for western settlement. A similar expansion of agricultural lands in countries such as Canada, Argentina, and Australia compounded these problems in the international market, where much of U.S. agricultural production was now sold.

The farther west the settlers went, the more dependent they became on the railroads to move their goods to market. At the same time, farmers paid high costs for manufactured goods as a result of the protective tariffs that Congress, backed by Eastern industrial interests, had long supported. Over time, the Midwestern and Western farmer fell ever more deeply in debt to the banks that held their mortgages.

In the South, the fall of the Confederacy brought major changes in agricultural practices. The most significant of these was sharecropping, where tenant farmers "shared" up to half of their crop with the landowners in exchange for seed and essential supplies. An estimated 80 percent of the South's African American farmers and 40 percent of its white ones lived under this debilitating system following the Civil War.

Most sharecroppers were locked in a cycle of debt, from which the only hope of escape was increased planting. This led to the over-production of cotton and tobacco, and thus to declining prices and the further exhaustion of the soil. The first organized effort to address general agricultural problems was the Granger movement. Launched in 1867 by employees of the U.S. Department of Agriculture, the Granges focused initially on social activities to counter the isolation most farm families encountered. Women's participation was actively encouraged. Spurred by the Panic of 1873, the Grange soon grew to 20,000 chapters and one-and-a-half million members.

Although most of them ultimately failed, the Granges set up their own marketing systems, stores, processing plants, factories and cooperatives. The movement also enjoyed some political success during the 1870s. A few states passed "Granger laws," limiting railroad and warehouse fees.

By 1880 the movement began to decline, replaced by the Farmers' Alliances. By 1890 the Alliance movements had members from New York to California totaling about 1.5 million. A parallel African American organization, the Colored Farmers National Alliance, numbered over a million members.

From the beginning, the Farmers' Alliances were political organizations with elaborate economic programs. According to one early platform, its purpose was to "unite the farmers of America for their protection against class legislation and the encroachments of concentrated capital." Their program also called for the regulation -- if not the outright nationalization -- of the railroads; currency inflation to provide debt relief; the lowering of the tariff; and the establishment of government-owned storehouses and low-interest lending facilities.

During the late 1880s a series of droughts devastated the western Great Plains. Western Kansas lost half its population during a four-year span. To make matters worse, the McKinley Tariff of 1890 was one of the highest the country had ever seen.

By 1890 the level of agrarian distress was at an all-time high. Working with sympathetic Democrats in the South or small third parties in the West, the Farmer's Alliance made a push for political power. From these elements, a third political party, known as the Populist Party, emerged. Never before in American politics had there been anything like the Populist fervor that swept the prairies and cotton lands. The elections of 1890 brought the new party into coalitions that controlled part of state government in a dozen Southern and Western states, and sent a score of Populist senators and representatives to Congress.

Its first convention was in 1892, when delegates from farm, labor and reform organizations met in Omaha, Nebraska, determined at last to make their mark on a U.S. political system they viewed as hopelessly corrupted by the monied interests of the industrial and commercial trusts.

The pragmatic portion of their platform focused on issues of land, transportation, and finance, including the unlimited coinage of silver. The Populists showed impressive strength in the West and South in the 1892 elections, and their candidate for president polled more than a million votes. Yet it was the currency question, pitting advocates of silver, against those who favored gold, which soon overshadowed all other issues. Agrarian spokesmen in the West and South demanded a return to the unlimited coinage of silver. Convinced that their troubles stemmed from a shortage of money in circulation, they argued that increasing the volume of money would indirectly raise prices for farm products and drive up industrial wages, thus allowing debts to be paid with inflated currency. Conservative groups and the financial classes, on the other hand, believed that such a policy would be disastrous, and insisted that inflation, once begun, could not be stopped. Railroad bonds were the most important financial instrument; they were payable in gold. But if fares and freight rates were set in helf-price silver dollars, each railroad would go bankrupt in weeks, throwing hundreds of thousands of men out of work and destroying the industrial economy. Only the gold standard, they said, offered stability.

The financial Panic of 1893 heightened the tension of this debate. Bank failures abounded in the South and Midwest; unemployment soared and crop prices fell badly. The crisis, and President Grover Cleveland's inability to solve it, nearly broke the Democratic Party. Democrats who were silver supporters absorbed the failing remnants of the Populist movement as the presidential elections of 1896 neared.

The Democratic convention that year was witness to one of the most famous speeches in U.S. political history. Pleading with the convention not to "crucify mankind on a cross of gold," William Jennings Bryan, the young Nebraskan champion of silver, won the Democrats' presidential nomination. The Populists also endorsed Bryan. Their power was fading fast and the best they could hope for was to have a voice inside the Bryan movement. Despite carrying the South and all of the West except California and Oregon, Bryan lost the more populated, industrial North and East -- and the election -- to the Republican's William McKinley.

The following year the country's finances began to improve, mostly die to restored business confidence. Silverites -- who did not realize that most transactions were handled by bank checks, not sacks of gold, falsely claimed the new prosperity was due to the discovery of gold in the Yukon. In 1898 the Spanish-American War drew the nation's attention further from Populist issues. If the movement was dead, however, its ideas were not. Once the Populists supported an idea it became tainted so that the vast majority of politicians rejected it; only years later after the taint had been forgotten was it possible to have, for example, direct election of Senators.

Workers' struggle

The life of a 19th-century U.S. industrial worker was far from easy. Even in good times wages were low, hours long and working conditions hazardous. As published in McClure's Magazine in 1894: "[The coal mine workers] breathe this atmosphere until their lungs grow heavy and sick with it" for only "fifty-five cents a day each." Little of the wealth generated went to the proletariat. The situation was worse for women and children, who made up a high percentage of the work force in some industries and often received but a fraction of the wages a man could earn. Periodic economic crises swept the nation, further eroding industrial wages and producing high levels of unemployment.

The elimination of competition, and the creation of monopolies, often forced workers to work for specific companies. Although the Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890 forbade the existence of monopolies as a "felony," major corporations found loopholes that allowed them to continue controlling national industries. The companies usually demanded long hours of exhausting work for low pay.

At the same time, the technological improvements, which added so much to the nation's productivity, continually reduced the demand for skilled labor. Yet the unskilled labor pool was constantly growing, as unprecedented numbers of immigrants -- 18 million between 1880 and 1910 -- entered the country, eager for work.

Before 1874, when Massachusetts passed the nation's first legislation limiting the number of hours women and child factory workers could perform to 10 hours a day, virtually no labor legislation existed in the country. Indeed, it was not until the 1930s that the federal government would become actively involved. Until then, the field was left to the state and local authorities, few of whom were as responsive to the workers as they were to wealthy industrialists.

The laissez-faire capitalism, which dominated the second half of the 19th century and fostered huge concentrations of wealth and power, was backed by a judiciary which time and again ruled against those who challenged the system. In this, they were merely following the prevailing philosophy of the times. As John D. Rockefeller is reported to have said: "the growth of a large business is merely a survival of the fittest." This "Social Darwinism," as it was known, had many proponents who argued that any attempt to regulate business was tantamount to impeding the natural evolution of the species.

Yet the costs of this indifference to the victims of capital were high. For millions, living and working conditions were poor, and the hope of escaping from a lifetime of poverty slight. That industrialization tightened the net of poverty around America's workers was even admitted by corporate leaders, such as Andrew Carnegie, who noted "the contrast between the palace of the millionaire and the cottage of the laborer." As late as the year 1900, the United States had the highest job-related fatality rate of any industrialized nation in the world. Most industrial workers still worked a 10-hour day (12 hours in the steel industry), yet earned from 20 to 40 percent less than the minimum deemed necessary for a decent life. The situation was only worse for children, whose numbers in the work force doubled between 1870 and 1900.

Labor organization

KOLlarge.jpeg

The first major effort to organize workers' groups on a nationwide basis appeared with The Noble Order of the Knights of Labor in 1869. Originally a secret, ritualistic society organized by Philadelphia garment workers, it was open to all workers, including African Americans, women and farmers. The Knights grew slowly until they succeeded in facing down the great railroad baron, Jay Gould, in an 1885 strike. Within a year they added 500,000 workers to their rolls.

The Knights of Labor soon fell into decline, however, and their place in the labor movement was gradually taken by the American Federation of Labor (AFL). Rather than open its membership to all, the AFL, under former cigar union official Samuel Gompers, focused on skilled workers. His objectives were "pure and simple": increasing wages, reducing hours and improving working conditions. As such, Gompers helped turn the labor movement away from the socialist views earlier labor leaders had espoused.

Still, labor's goals -- and the unwillingness of capital to grant them -- resulted in the most violent labor conflicts in the nation's history. The first of these occurred was the Great Railroad Strike in 1877, when rail workers across the nation went out on strike in response to a 10-percent pay cut. Attempts to break the strike led to a full scale working class uprising in several cities: Baltimore, Maryland; Chicago, Illinois; Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania; Buffalo, New York; and San Francisco, California.

The military was called in at several locations before the strike to crush the uprising workers. The Haymarket Square incident took place nine years later, when someone threw a bomb into a meeting called to discuss an ongoing strike at the McCormick Harvester Company in Chicago. In the ensuing battle, nine people were killed and some 60 injured. Next came the riots of 1892 at Carnegie's steel works in Homestead, Pennsylvania.

A group of 300 Pinkerton detectives the company had hired to break a bitter strike by the Amalgamated Association of Iron, Steel and Tin Workers were fired upon and 10 were killed. The National Guard was called in as a result to crush the striking workers; non-union workers were hired and the strike broken. Unions were not let back into the plant until 1937.

Two years later, wage cuts at the Pullman Palace Car Company just outside Chicago, led to a strike, which, with the support of the American Railway Union, soon brought the nation's railway industry to a halt. As usual, as soon as labor exerted its immense power over capital, the federal government steped in and weighed in on the side of capital by force. U.S. Attorney General Richard Olney, himself a former lawyer for the railroad industry, deputized over 3,000 men in an attempt to keep the rails open. This was followed by a federal court injunction against union interference with the trains.

When workers refused to kowtow to the manuverings of the railroad industry and their agents in the federal government, Cleveland -- again -- sent in federal troops, and the strike was eventually broken. The most militant working class organization of the time was the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). Formed from an amalgam of unions fighting for better conditions in the West's mining industry, the IWW, or "Wobblies" as they were commonly known, gained particular prominence from the Colorado mine clashes of 1903 and the singularly brutal fashion in which they were put down. Openly calling for class warfare, the Wobblies gained many adherents after they won a difficult strike battle in the textile mills of Lawrence, Massachusetts, in 1912. Their call for work stoppages in the midst of World War I, however, led to a government crackdown in 1917, which virtually destroyed them.

The rise of U.S. Imperialism

The findings of the 1890 Census, popularized by historian Frederick Jackson Turner in his paper entitled The Significance of the Frontier in American History, contributed to fears of dwindling natural resources. The Panic of 1893 and the ensuing depression also led some businessmen and politicians to come to the same conclusion as influential European imperialists (e.g., Leopold II of Belgium, Jules Ferry, Benjamin Disraeli, Joseph Chamberlain, and Francesco Crispi) had reached nearly a generation earlier in Europe: that industry had apparently over-expanded, producing more goods than domestic consumers could buy.

Like the Long Depression in Europe, which bred doubts regarding growing strength of political resistance of world capitalism, the main features of the Panic of 1893 included deflation, rural decline, and unemployment (indicative of under-consumption), which aggravated the bitter social protests of the Gilded Age, the Populist movement, the free-silver crusade, and violent labor disputes such as the Pullman Strike.

Similarly, the post-1873 in Europe period saw a reemergence of far more militant working-class organization and cycles of large strikes. The rapid turn to the "New Imperialism" in the late nineteenth century can be correlated with cyclically spaced economic depressions that adversely affected many elite groups. Like the Long Depression, an era of increasing unemployment and deflated prices for manufactured goods, the Panic of 1893 contributed to fierce competition over markets in the growing "spheres of influence" of the United States, which tended to overlap with Britain's, especially in the Pacific and South America.

Some U.S. politicians, such as Henry Cabot Lodge, William McKinley, and Theodore Roosevelt, advocated a more aggressive foreign policy and a policy of to pull the United States out of the depression of the second Grover Cleveland administration.

Just as the German Reich reacted to depression with the adoption of protective tariff protection in 1879, so would the United States with the landslide election victory of William McKinley, who had risen to national prominence six years earlier with the passage of the McKinley Tariff of 1890.

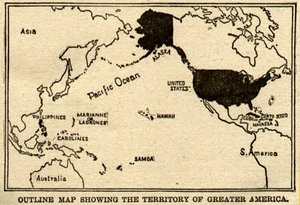

As Germany emerged as a great power after victory in the Franco-Prussian War completed the process of its unification, the U.S. would emerge as a great power after victory in the Civil War. Like newly industrializing great powers, the U.S. adopted protectionism, seized a colonial empire of its own (1898), and built up a powerful navy (the "Great White Fleet)." On the Pacific, since the Meiji Restoration, Japan's development followed a similar pattern, following the Western lead in industrialization and militarism, enabling it to gain a foothold or "sphere of influence" in Qing China.

Although U.S. capital investments within the Philippines and Puerto Rico were relatively small (figures that would seemingly detract from the broader economic implications on first glance), these colonies were strategic outposts for expanding trade with Asia, particularly China and Latin America.

U.S. imperialism was marked by the reaffirmation of the Monroe Doctrine, formalized by the Roosevelt Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine in 1904.

The Philippine-American War

For details see the main article Philippine-American War.

Nevertheless, the United States found itself in a familiar colonial role when it suppressed an armed independence movement in the Philippines in the first decade of its occupation. During the ensuing (and largely forgotten) Philippine-American War, 4,234 U.S. soldiers were killed, and thousands more were wounded. Philippine military deaths were estimated at roughly 20,000. Filipino civilian deaths are unknown, but some estimates place them as high as one million.

U.S. attacks into the countryside often included scorched earth campaigns where entire villages were burned and destroyed, torture (water cure) and the concentration of civilians into "protected zones." Many of these civilian casualties resulted from disease and famine. Reports of the execution of U.S. soldiers taken prisoner by the Filipinos led to disproportionate reprisals by American forces. Many U.S. officers and soldiers called the war a "nigger killing business."

During the U.S. occupation, English was declared the official language, although the languages of the Philippine people were Spanish, Visayan, Tagalog, Ilokano and other native languages. Six hundred American teachers were imported aboard the U.S.S. Thomas. Also, the Catholic Church was disestablished, and a considerable amount of church land was purchased and redistributed.

In 1914, Dean C. Worcester, U.S. Secretary of the Interior for the Philippines (1901-1913) described "the regime of civilization and improvement which started with American occupation and resulted in developing naked savages into cultivated and educated men."

The "progressive" era

The presidential election of 1900 gave the U.S. a chance to pass judgment on the McKinley administration, especially its foreign policy. Meeting at Philadelphia, the Republicans expressed jubilation over the successful outcome of the war with Spain, the restoration of prosperity and the effort to obtain new markets through the "Open Door" policy. McKinley's election was a foregone conclusion.

But the president did not live long enough to enjoy his victory. In September 1901, while attending an exposition in Buffalo, New York, McKinley was shot down by an assassin. (He was the third president to be assassinated since the Civil War.) Theodore Roosevelt, McKinley's vice president, assumed the presidency.

In domestic as well as international affairs, Roosevelt's accession coincided with a new epoch in American political life. The continent was peopled with non-Natives; the frontier was disappearing. The country's political foundations had endured the vicissitudes of foreign and civil war, the tides of prosperity and depression. Immense strides had been made in agriculture and industry.

However, the influence of big business was now more firmly entrenched than ever, and local and municipal government often was in the hands of corrupt politicians. A new spirit of the times known as "progressivism" emerged from approximately 1890 until the U.S. entry into World War I in 1917.

Many self-styled "progressives" saw their work as a crusade against urban political bosses and corrupt "robber barons." The era saw increased demands for effective regulation of business, a revived commitment to public service, and expanding the scope of government to ensure the welfare and interests of the country as the groups pressing these demands saw fit. Almost all the notable figures of the period, whether in politics, philosophy, scholarship or literature, were connected, at least in part, with the reform movement.

Years before, in 1873, the celebrated author Mark Twain had exposed American society to critical scrutiny in "The Gilded Age." Now, trenchant articles dealing with trusts, high finance, impure foods and abusive railroad practices began to appear in the daily newspapers and in such popular magazines as McClure's and Collier's. Their authors, such as the journalist Ida M. Tarbell, who crusaded against the Standard Oil Trust, became known as "muckrakers." In his sensational novel, The Jungle (http://www.gutenberg.org/catalog/world/results), Upton Sinclair exposed unsanitary conditions in the great Chicago meat packing houses and the grip of the beef trust on the nation's meat supply.

The hammering impact of "progressive" era writers bolstered aims of certain sectors of the population, especially a middle class caught between big labor and big capital, to take political action. Many states enacted laws to improve the conditions under which people lived and worked. At the urging of such prominent social critics as Jane Addams, child labor laws, were strengthened and new ones adopted, raising age limits, shortening work hours, restricting night work and requiring school attendance.

The Roosevelt presidency

By the early 20th century, most of the larger cities and more than half the states had established an eight-hour day on public works. Equally important were the workmen's compensation laws, which made employers legally responsible for injuries sustained by employees at work. New revenue laws were also enacted, which, by taxing inheritances, laid the groundwork for the contemporary federal income tax.

Roosevelt called for a "Square Deal," and initiated a policy of increased federal supervision in the enforcement of antitrust laws. Later, extension of government supervision over the railroads prompted the passage of major regulatory bills. One of the bills made published rates the lawful standard, and shippers equally liable with railroads for rebates.

His victory in the 1904 election was assured. Emboldened by a sweeping electoral triumph, Roosevelt called for still more drastic railroad regulation, and in June 1906 Congress passed the Hepburn Act. This gave the Interstate Commerce Commission real authority in regulating rates, extended the jurisdiction of the commission and forced the railroads to surrender their interlocking interests in steamship lines and coal companies.

Meanwhile, Congress had created a new Department of Commerce and Labor, with membership in the president's Cabinet. One bureau of the new department, empowered to investigate the affairs of large business aggregations, discovered in 1907 that the American Sugar Refining Company had defrauded the government of a large sum in import duties. Subsequent legal actions recovered more than $4 million and convicted several company officials.

Conservation of the nation's natural resources was among the other facets of the Roosevelt era. The president had called for a far-reaching and integrated program of conservation, reclamation and irrigation as early as 1901 in his first annual message to Congress. Whereas his predecessors had set aside 188,000 km² of timberland for preservation and parks, Roosevelt increased the area to 592,000 km² and began systematic efforts to prevent forest fires and to retimber denuded tracts.

Taft and Wilson

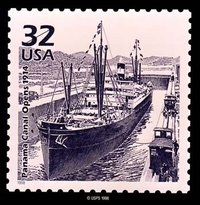

Roosevelt's popularity was at its peak as the campaign of 1908 neared, but he was unwilling to break the tradition by which no president had held office for more than two terms. Instead, he supported William Howard Taft, who won the election and sought to continue his predecessor's programs of reform. Taft, a former judge, first (and beloved) colonial governor of the U.S-held Philippines and administrator of the Panama Canal, made some progress. (For details on U.S. foreign policy under the Taft administration, see Dollar Diplomacy.)

He continued the prosecution of trusts, further strengthened the Interstate Commerce Commission, established a postal savings bank and a parcel post system, expanded the civil service and sponsored the enactment of two amendments to the Constitution. The 16th Amendment authorized a federal income tax; the 17th Amendment, ratified in 1913, mandated the direct election of senators by the people, replacing the system whereby they were selected by state legislatures.

Yet balanced against these achievements was Taft's acceptance of a tariff with protective schedules that outraged liberal opinion; his opposition to the entry of the state of Arizona into the Union because of its liberal constitution; and his growing reliance on the conservative wing of his party. By 1910 Taft's party was divided, and an overwhelming vote swept the Democrats back into control of Congress.

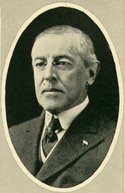

Two years later, Woodrow Wilson, the Democratic, progressive governor of the state of New Jersey, campaigned against Taft, the Republican candidate, and against Roosevelt who, rejected as a candidate by the Republican convention, had organized a third party, the Progressives.

Wilson, in a spirited campaign, defeated both rivals. Under his leadership, the new Congress enacted one of the most notable legislative programs in American history. Its first task was tariff revision. "The tariff duties must be altered," Wilson said. "We must abolish everything that bears any semblance of privilege." The Underwood Tariff, signed on October 3, 1913, provided substantial rate reductions on imported raw materials and foodstuffs, cotton and woolen goods, iron and steel, and removed the duties from more than a hundred other items. Although the act retained many protective features, it was a genuine attempt to lower the cost of living.

The second item on the Democratic program was a long overdue, thorough reorganization of the inflexible banking and currency system. "Control," said Wilson, "must be public, not private, must be vested in the government itself, so that the banks may be the instruments, not the masters, of business and of individual enterprise and initiative."

The Federal Reserve Act of December 23, 1913, was one of Wilson's most enduring legislative accomplishments. It imposed upon the existing banking system a new organization that divided the country into 12 districts, with a Federal Reserve Bank in each, all supervised by a Federal Reserve Board. These banks were to serve as depositories for the cash reserves of those banks that joined the system. Until the Federal Reserve Act, the U.S. government had left control of its money supply largely to unregulated private banks. While the official medium of exchange was gold coins, most loans and payments were carried out with bank notes, backed by the promise of redemption in gold. The trouble with this system was that the banks were tempted to reach beyond their cash reserves, prompting periodic panics during which fearful depositors raced to turn their bank paper into coin.

With the passage of the act, greater flexibility in the money supply was assured, and provision was made for issuing federal reserve notes to meet business demands. The next important task was trust regulation and investigation of corporate abuses. Congress authorized a Federal Trade Commission to issue orders prohibiting "unfair methods of competition" by business concerns in interstate trade.

A second law, the Clayton Antitrust Act, forbade many corporate practices that had thus far escaped specific condemnation -- interlocking directorates, price discrimination among purchasers, use of the injunction in labor disputes and ownership by one corporation of stock in similar enterprises.

The Federal Workingman's Compensation Act in 1916 authorized allowances to civil service employees for disabilities incurred at work. The Adamson Act of the same year established an eight-hour day for railroad labor. The record of achievement won Wilson a firm place in American history as one of the nation's foremost political reformers. However, his domestic reputation would soon be overshadowed by his record as a wartime president who led his country to victory but could not hold the support of his people for the peace that followed.

World War I

Main article: World War I

During the 20th century the U.S. was involved in two World Wars. Firmly maintaining neutrality when World War I began in 1914, the United States entered the war after the RMS Lusitania, a British ship carrying many American passengers, was sunk by German submarines. With American help, Britain, France and Italy won the war, and imposed severe economic penalties on Germany in the Treaty of Versailles. The United States Senate did not ratify the Treaty of Versailles; instead, the United States signed separate peace treaties with Germany and her allies. Despite President Woodrow Wilson's calls for agreeable terms, the economic impact of the reparations mandated by the Treaty were severe. Thanks to the American-sponsored Dawes Plan Germany regained prosperity in the mid 1920s and seemed on its way to becoming a stable democracy. The rise of the Nazi and Communist parties, which used violence as their main tool, combined with sepression after 1929, led to the election of Adolf Hitler in Germany in 1933. The U.S. Senate refused to join the League of Nations on Wilson's terms, and Wilson rejected the Senate's compromise proposal. So the U.S. never did join the League, which in any case proved totally ineffective in dealing with major issues.

Clip Art and Pictures

- Historical Pictures of the United States (http://classroomclipart.com/cgi-bin/kids/imageFolio.cgi?direct=History/United_States)

- Pictures of the American Revolution (http://classroomclipart.com/cgi-bin/kids/imageFolio.cgi?direct=History/United_States/American_Revolution)

- Civil Rights Pictures (http://classroomclipart.com/cgi-bin/kids/imageFolio.cgi?direct=History/United_States/Civil_Rights)

- Civil War Images (http://classroomclipart.com/cgi-bin/kids/imageFolio.cgi?direct=History/United_States/Civil_War)

- Pictures of Colonial America (http://classroomclipart.com/cgi-bin/kids/imageFolio.cgi?direct=History/United_States/Colonial_America)

- Historical US Illustrations (http://classroomclipart.com/cgi-bin/kids/imageFolio.cgi?direct=History/United_States/Illustrations)

- Photographs of the US Presidents (http://classroomclipart.com/cgi-bin/kids/imageFolio.cgi?direct=History/United_States/Presidents)

- World War II Pictures (http://classroomclipart.com/cgi-bin/kids/imageFolio.cgi?direct=History/United_States/World_War_II)

- Pictures of Historical People (http://classroomclipart.com/cgi-bin/kids/imageFolio.cgi?direct=History/United_States/People)

Lesson Plans, Resources and Activites

- US History Lesson Plans (http://lessonplancentral.com/lessons/Social_Studies/US_History/index.htm)

- American Revolution Lesson Plans (http://lessonplancentral.com/lessons/Social_Studies/US_History/American_Revolution/index.htm)

- Colonial America Lesson Plans (http://lessonplancentral.com/lessons/Social_Studies/US_History/Colonial_Times/index.htm)

- Great Depression Lesson Plans (http://lessonplancentral.com/lessons/Social_Studies/US_History/Great_Depression/index.htm)

- Westward Expansion Lesson Plans (http://lessonplancentral.com/lessons/Social_Studies/US_History/Westward_Expansion/index.htm)

State Maps

- US State Maps (http://classroomclipart.com/cgi-bin/kids/imageFolio.cgi?direct=Clipart/US_State_Maps)

State Flags

- US State Flags (http://classroomclipart.com/cgi-bin/kids/imageFolio.cgi?direct=Clipart/State_Flags)

References and External Links

- United States History (http://encarta.msn.com/encyclopedia_1741500823_10/United_States_(History).html#s98) from the Encarta Encyclopedia.

- Library of Congress on American History (http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/)

- Native American History Links (http://www.csulb.edu/projects/ais/)

- Fordham University Links on American Imperialism (http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/mod/modsbook34.html#American%20Imperialism)

- Labor History Links from U. Connecticut (http://www.lib.uconn.edu/online/research/speclib/ASC/BLC/Laborlinks.htm)

| History of the United States: timeline & topics | Missing image Flag_of_the_United_States.png Flag of the United States | |

|---|---|---|

| ||