Dollar Diplomacy

|

|

Dollar Diplomacy is the term used to describe the efforts of the United States—particularly under President William Howard Taft—to further its foreign policy aims in Latin America and East Asia through use of its economic power. The term was originally coined by President Taft, who claimed that U.S. operations in Latin America went from 'warlike and political' to 'peaceful and economic.'

The term is also used historically by Latin Americans to show their disapproval of the role of that the U.S. government and U.S. corporations have played in using economic, diplomatic, and military power to open up foreign markets.

| Contents |

Taft and Knox

The thrust of Taft's foreign policy was best represented by the man he chose to administer it: Secretary of State Philander C. Knox, a corporate lawyer committed to using his position to promote U.S. business interest abroad. Knox regarded the State Department as effectively an agent of the corporate community. He worked aggressively to extend U.S. investments into underdeveloped regions, motivating observers to label his policies "Dollar Diplomacy."

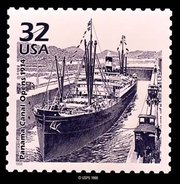

Thus, Washington warmly encouraged U.S. bankers to sluice their surplus dollars into foreign areas of strategic concern to the United States, especially in East Asia and in the regions critical to the security of the Panama Canal. Otherwise, investors from rival powers, such as Germany, might take advantage of financial chaos and secure a lodgment inimical to the interests of the U.S. financial and corporate community. U.S. bankers would thus promote the strengthening of U.S. military power, while bringing further prosperity to themselves.

"Dollar Diplomacy" in the Americas

Outgoing President Theodore Roosevelt laid the groundwork for this approach in 1904 with his Roosevelt Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine (under which U.S. marines were frequently sent to Central America) maintaining that if any nation in the Western Hemisphere appeared politically and fiscally so unstable as to be vulnerable to European control, the United States had the right and obligation to intervene.

Taft continued and expanded this policy, starting in Central America, where he justified it as a means of protecting the Panama Canal. In 1909 he attempted unsuccessfully to establish control over Honduras by buying up its debt to British bankers.

Dollar Diplomacy was not always peaceful. In Nicaragua, U.S. intervention involved participating in the overthrow of one government and the military support of another. When a revolt broke out in Nicaragua in 1909, the Taft administration quickly sided with the insurgents (who had been instigated by U.S. mining interests) and sent U.S. troops into the country to seize the customs houses. As soon as the U.S. consolidated control over the country, Knox encouraged U.S. bankers to move into the country and offer substantial loans to the new regime, thus increasing U.S. financial leverage over the country. Within two years, however, the new pro-U.S. regime faced a revolt of its own; and, once again, the administration landed U.S. troops in Nicaragua, this time to protect the tottering, corrupt U.S. puppet regime. U.S. troops remained there for over a decade.

Another dangerous new trouble spot was the revolution-riddled Caribbean—now largely dominated by U.S. interests. Hoping to head off trouble, Washington urged U.S. bankers to pump dollars into the financial vacuum in Honduras and Haiti to keep out foreign funds. The United States would not permit foreign nations to intervene, and consequently felt obligated to prevent economic and political instability. The State Department persuaded four U.S. banks to refinance Haiti's national debt, setting the stage for further intervention in the future.

"Dollar Diplomacy" in East Asia

The Taft-Knox foreign policy faced its severest test, and encountered its greatest failure, in East Asia. Ignoring Roosevelt's tacit 1905 agreement with Japan to limit U.S. involvement in Manchuria, the new administration succumbed to the persuasive powers of U.S. bankers and began to move aggressively to increase U.S. economic influence in the region.

When British, French, and German bankers formed a consortium to finance a vast system of railroads in China, Knox became convinced in 1910 that the United States' free access to trade there was threatened by European financing of the new Hukuang Railroad. Knox insisted that the U.S. also participate. In 1911 the Europeans finally agreed to include the U.S. in their venture. The Taft administration arranged for U.S. bankers to be included in the project and then prevailed on J. Pierpont Morgan to create a U.S. syndicate for the purpose.

Knox was also concerned about Russian and Japanese railroad activities in Manchuria. Just as the Europeans were finally agreeing to include the U.S. in their Hukuang Railroad venture, Knox proposed that an international syndicate purchase outright —as opposed to merely provide financing for —the South Manchurian Railroad to remove it from Japanese control and managed to persuade U.S. bankers to join a six-power consortium that would give China money instead.

Both Japan and Tsarist Russia, unwilling to be jockeyed out of their dominant position, bluntly rejected Knox's overtures. Japan responded by signing a friendship treaty with Russia—a warning to the Europeans—and the entire railroad project quickly collapsed. Having attempted to expand its influence in East Asia, the U.S. now found Manchuria cordoned off from U.S. imperialism. Taft was showered with ridicule.

Repudiation by President Wilson

The Taft-Knox approach to foreign policy was repudiated by President Woodrow Wilson within a few weeks of his inauguration in 1913. Although he did not abstain from Caribbean intervention, dollar diplomacy was no longer an explicit U.S. national policy.