Imperialism in Asia

|

|

| This article is part of the New Imperialism series. |

| Origins of New Imperialism |

| Imperialism in Asia |

| Scramble for Africa |

| Imperial rivalry |

| Theories of New Imperialism |

Large areas of Asia, as well as Africa and other areas of the world, were subjected to imperial control by European nations, China, and Japan.

There are many reasons why this could happen with such relative ease and to the extent it did: the Industrial Revolution had not yet spread to these regions, making the weapons their peoples possessed generally inferior to those of the Europeans; military organization was on the whole weaker than in Europe; governments tended to be unrepresentative; the survival of ethnic and tribal loyalties at the expense of nationalist feeling and the prevalence of mass illiteracy impeded the development of cohesive societies and strong administration; and the presence of valuable raw materials and abundant cheap labor exerted a powerful attraction.

| Contents |

The Partitioning of Asia by the Europeans

- India - French, Dutch and British before British expanded control in 1757.

- Sri Lanka- conquered by Portugal (1505), the Netherlands (1656), and then Britain (1796). It had tea and rubber.

- Macau - Portuguese colony, first European colony in China (1557-1999).

- Hong Kong - British colony from 1841 to 1997.

- Malaya- Portuguese then Dutch then British; rich in tin and rubber.

- Singapore - British since 1819.

- Burma - merged with India by the British from 1886 to 1937. In 1880, the French built a railroad from Tonkin to Mandalay: fearing a French conquest, the British went to war with Burma. The Burmese king was captured and sent to India during the war.

- Indonesia and surrounding islands - occupied by the Dutch.

- Indo-China - French; including Laos, Cambodia, and Vietnam. Successive revolts were "pacified"

- Thailand - nominally independent, but subject to British and French influence.

- Philippines - Spanish until revolt of 1896, then acquired by the U.S. after the Spanish-American War of 1898 for $20 million.

- Korea - Nominally independent (until 1910) but subject to Russian influence

The British in India

The collapse of Mughal India and the rise of the British East India Company

Main article: Company rule in India The British East India Company, formed in 1600, although still in direct competition with French and Dutch interests until 1763, was able to extend its control over almost the whole of the subcontinent in the century following the subjugation of Bengal at the 1757 Battle of Plassey. The British East India Company made great advances at the expense of a Mughal dynasty, seething with corruption, oppression, and revolt, that was crumbling under the despotic rule of Aurangzeb (1658-1707).

The reign of Shah Jahan (1628-1658) had marked the height of Mughal power. However, the reign of Aurangzeb, a ruthless and fanatical man who intended to rid India of all views alien to the Muslim faith, was disastrous. By 1690, when Mughal territorial expansion reached its greatest extent, Aurangzeb's India encompassed the entire Indian peninsula. But this period of power was followed by one of decline. Fifty years after the death of Aurangzeb, the great Mughal empire had crumbled. Meanwhile, marauding warlords, nobles, and others bent on gaining power left the subcontinent increasingly anarchic. Although the Mughals kept the imperial title until 1858, the central government had collapsed, creating a power vacuum.

From Company to Crown

Main article: British Raj

Meanwhile, English and French trading companies had been competing against one another for more than a century, and by the middle of the 18th century a monumental battle for empire was engaged. During the Seven Years' War (1756-1763) Robert Clive, the leader of the Company in India, defeated a key Indian ruler of Bengal at the decisive Battle of Plassey (1757), a victory that ushered in the beginning of a new period in Indian history, that of informal British rule. While still nominally the sovereign, the Mughal Indian emperor became more and more of a puppet ruler, and anarchy spread until the company stepped into the role of policeman of India.

The transition to formal imperialism, characterized by Queen Victoria being crowned "Empress of India" in the 1870s was a gradual process. The first step toward cementing formal British control extended back to the late 18th century. The British Parliament, disturbed by the idea that a great business concern, interested primarily in profit, was controlling the destinies of millions of people, passed acts in 1773 and 1784 that gave itself the power to control company policies and to appoint the highest company official in India, the governor-general. (This system of dual control lasted until 1858.) By 1818 the East India Company was master of India. Some local rulers were forced to accept its overlordship; others were deprived of their territories. Some portions of the subcontinent were administered by the British directly; in others native dynasties were retained under British supervision.

Until 1858, however, much of the subcontinent was still officially the dominion of the Mughal emperor. Anger among some social groups, however, was seething under the governor-generalship of James Dalhousie (1847-1856), who annexed the Punjab (1849) after victory in the Second Sikh War, annexed seven princely states on the basis of lapse, annexed the key state of Oudh on the basis of misgovernment, and upset cultural sensibilities by banning Hindu practices such as Sati. The 1857 Sepoy Rebellion, or Indian Mutiny (called First Indian War of Independence by Indian Nationalists), an uprising initiated by Indian troops, called sepoys, who formed the bulk of the Company's armed forces, was the key turning point. Fortunately for the British, many areas remained loyal and quiescent, allowing the revolt to be crushed after fierce fighting. One important consequence of the revolt was the final collapse of the Mughal dynasty. The mutiny also ended the system of dual control under which the British government and the British East India Company shared authority. The government relieved the company of its political responsibilities, and in 1858, after 258 years of existence, the company relinquished its role. Trained civil servants were recruited from graduates of British universities, and these men set out to rule India. Lord Canning (created earl in 1859), appointed governor-general of India in 1856, became known as "Clemency Canning" as a term of derision for his efforts to restrain revenge against the Indians during the Indian Mutiny. When the government of India was transferred from the Company to the Crown, Canning became the first viceroy of India.

The rise of Indian nationalism

Main article: Indian independence movement British rule modernized India in many respects. The spread of railroads from 1853 contributed to the expansion of business, while cotton, tea and indigo plantations drew new areas into the commercial economy. But the removal of import duties in 1883 exposed India's emerging industries to unfettered British competition, provoking another quite modern development: the rise of a nationalist movement.

The denial of equal status to Indians was the immediate stimulus for the formation in 1885 of the Indian National Congress, initially loyal to the Empire but committed from 1905 to increased self-government and by 1930 to outright independence. The "Home charges," payments transferred from India for administrative costs, were a lasting source of nationalist grievance, though the flow declined in relative importance over the decades to independence in 1947.

Although majority Hindu and minority Muslim political leaders were able to collaborate closely in their criticism of British policy into the 1920s, British support for a distinct Muslim political organization from 1906 and insistence from the 1920s on separate electorates for religious minorities, is seen by many in India as having contributed to Hindu-Muslim discord and the country's eventual partition.

France in Indochina

In contrast to Britain, France, which had lost its empire to the British by the end of the eighteenth century, had little geographical or commercial basis for expansion in Southeast Asia. After the 1850s French imperialism was initially impelled by a nationalistic need to rival Britain and was supported intellectually by the concept of the superiority of French culture and France's special "mission civilisatrice"—the civilizing of the native through assimilation to French culture. The immediate pretext for French expansionism in Indochina was the protection of French religious missions in the area, coupled with a desire to find a southern route to China through Tonkin, the northern region of northern Vietnam.

French religious and commercial interests were established in Indochina as early as the seventeenth century, but no concerted effort at stabilizing the French position was possible in the face of British strength in the Indian Ocean and French defeat in Europe at the end of the eighteenth and beginning of the nineteenth centuries. A mid-nineteenth century religious revival under the Second Empire provided the atmosphere within which interest in Indochina grew. Anti-Christian persecutions in the Far East provided the immediate cause. In 1856 the Chinese executed a French missionary in southeastern China, and in 1857 the Vietnamese emperor, faced with a domestic crisis, tried to destroy foreign influences in his country by executing the Spanish bishop of Tonkin. Under Napoleon III, France decided that Catholicism would be eliminated in the Far East if France did not go to its aid, and accordingly the French joined the British against China from 1857 to 1860 and took action against Vietnam as well. By 1860 the French occupied Saigon.

By a Franco-Vietnamese treaty in 1862, the Vietnamese emperor ceded France outright the three provinces of Cochin China in the south; France also secured trade and religious privileges in the rest of Vietnam and a protectorate over Vietnam's foreign relations. Gradually French power spread through exploration, the establishment of protectorates, and outright annexations. Their seizure of Hanoi in 1882 led directly to war with China (1883-1885), and the French victory confirmed French supremacy in the region. France governed Cochin China as a direct colony, and Annam (central Vietnam), Tonkin, and Cambodia as protectorates in one degree or another. Laos too was soon brought under French "protection."

By the beginning of the twentieth century France had created an empire in Indochina nearly 50 percent larger than the mother country. A governor-general in Hanoi ruled Cochin China directly and the other regions through a system of residents. Theoretically, the French maintained the precolonial rulers and administrative structures in Annam, Tonkin, Cambodia, and Laos, but in fact the governor-generalship was a centralized fiscal and administrative regime ruling the entire region. Although the surviving native institutions were preserved in order to make French rule more acceptable, they were almost completely deprived of any independence of action. The ethnocentric French colonial administrators sought to assimilate the upper classes into France's "superior culture." While the French improved public services and provided commercial stability, the native standard of living declined and precolonial social structures to all intents and purposes in the process of erosion. Indochina, which had a population of over eighteen million in 1914, was important to France for its tin, pepper, coal, cotton, and rice. It is still a matter of debate, however, whether the colony was commercially profitable.

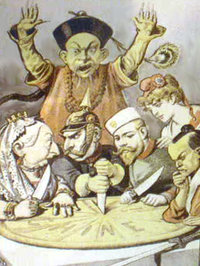

Imperialism in China

The Chinese have always called their country the "Middle Kingdom," by which was meant that it was surrounded by lesser powers that could not compare to China in culture and wealth. China was largely self-sufficient and, apart from furs from North America and grain from South East Asia, Europeans could find little the Chinese wanted to buy. They could only offer foreign silver, so that the Mexican Peso became the standard form of currency. In the twentieth century the US minted the Trade dollar, larger than the US silver dollar, to continue this trade.

During the 18th century Britain had already established a vigorous trade with China, exporting Mexican silver, and importing Chinese tea. But with the gradual but substantial loss of silver to China and subsequent monetary disruption, Britain needed some alternative export. After initial failure, Indian opium eventually proved a profitable, though morally questionable, replacement. While this solved Britain's balance of payments problem, it brought tremendous social costs on China and precipitated the Opium Wars between Britain and China starting in 1839.

British imperialism in 19th century China was also fostered by the mistaken notion that China was a natural market for British manufactured goods (chiefly textiles), and that Chinese disinterest in foreign manufactured goods was only due to excessive government trade restrictions. There is now a consensus among historians that Chinese restrictions on trade were not onerous, and that the British textiles were unable to compete because Chinese textiles were created by surplus labor within a family, and hence, unlike British textiles, it was unnecessary for the labor to be paid at subsistence rates.

Imperialist ambitions and rivalries in the Far East inevitably came to focus on the vast empire of China which contained more than a quarter of the world's population. That China survived as an independent state at all owes much to the resilience of her social and administrative structures, but can also be seen as a reflection of the real limits of European imperialism in the face of similar competing claims.

Formal colonies were often, in hindsight, strategic outposts to protect large zones of investment, such as India, Latin America, and China. But Britain, in a sense, continued to adhere to the Cobdenite notion that informal colonialism was preferable--the established consensus among industrial capitalists during the mid nineteenth century between the downfall of Napoleon and the Franco-Prussian War. What changed was not necessarily a preference for colonialism over informal empire, but the attitude toward formal rule in largely tropical areas once considered too 'backward' for trade. Sovereign areas already hospitable to informal empire largely avoided formal rule during the shift to New Imperialism.

China, for instance, was not a backward country unable to secure the prerequisite stability and security for Western-style commerce, but a highly advanced empire unwilling to admit Western commerce on terms acceptable to the West, which may explain the West's contentment with informal "Spheres of Influences". Following the First Opium War, British commerce, and later capital investment by other newly industrializing powers, was securable with a smaller degree of formal control than in Southeast Asia, West Africa, and the Pacific. Western powers did sometimes intervene militarily to quell violence, such as the horrific Taiping Rebellion and the anti-imperialist Boxer Rebellion. For example, General Gordon, later the imperialist 'martyr' in the Sudan, is often credited with having played a minor role in saving the Qing Dynasty from the Taiping insurrection.

It may also be argued, however, that China's size and cohesion compared to pre-colonial societies of Africa made formal subjugation too difficult for any but the broadest coalition of colonialist powers, whose own rivalries would preclude such an outcome. When such a coalition did materialize in 1900, its objective was limited to suppression of the anti-imperialist Boxer Rebellion because of the irreconcilability of Anglo-American aims (the "Open Door" according to which all powers would enjoy commercial access) and the territorial aspirations of Germany and Russia.

The British found it difficult to sell their products in China, and so experienced (in common with other European countries) a deficit in Chinese trade until the early 19th century. The start of a large-scale trade in opium from British India to China reversed the situation, creating widespread addiction among the population and threatening the country with immeasurable physical, moral, and psychological damage.

An attempt by Qing officials in Guangzhou (Canton) to stop the trade led to the First Opium War (1839-1842), in which the British easily defeated the Chinese and gained control of the island of Hong Kong. The Treaty of Nanjing recognized the principle of extraterritoriality, under which any British citizen charged with an offence in China would be tried by fellow Britons rather than in a Qing court. In effect this meant crimes against Chinese people went largely unpunished if committed by a Westerner.

The Second Opium War (1856-1860), in which Britain was joined by France following the death of a missionary and the search of a ship that claimed British protection, extended Britain's holding in Hong Kong to the adjacent mainland district of Kowloon. The Treaty of Tianjin gave the imperialist powers even more.

During the period 1894-1895, China lost a war against Japan over Korea, and China had to pay huge war reparations ($150 million) and give up Taiwan (Formosa) and nearby islands to Japan. Korea was recognized as nominally independent, but came under Japanese domination. Intervention by France, Germany and Russia prevented further Japanese annexations, an episode remembered with bitterness in Japan when the same powers helped themselves to Chinese naval bases and spheres of influence in 1897-1898.

Spheres of Influence

- Germany: Jiaozhou (Kiaochow) Bay, Shandong, Huang He (Hwang-Ho) valley.

- Russia: Liaodong Peninsula, railroad rights in Manchuria.

- Britain: Weihaiwei, Yangtze Valley

- France: Guangzhou Bay, three other southern provinces

John Hay, U.S. Secretary of the State at the time, called in September, 1899, for recognition by the powers of the principle of the "Open Door", denoting freedom of commercial access and non-annexation of Chinese territory. Supported by Britain and Japan, the U.S. stand helped to control the partitioning of China. In any event, it was in the European powers' interest to have a weak but independent Manchu government. The privileges of the Europeans in China were guaranteed in the form of treaties with the Qing government. In the event that the Qing government totally collapsed, each power risked losing the privileges that it already had negotiated. As such, nor was it in the interest of the Europeans to have an overly strong government in China, with the ability to control Westerners and renegotiate treaties.

The erosion of Chinese sovereignty contributed to a spectacular anti-foreign outbreak in June, 1900, when the "Boxers" (properly the society of the "righteous and harmonious fists") attacked European legations in Beijing, provoking a rare display of unity among the powers, whose troops landed at Tianjin and marched on the capital. German forces were particularly severe in exacting revenge for the killing of their Ambassador, while Russia tightened her hold on Manchuria in the northeast until its crushing defeat by Japan in the war of 1904-1905.

Although extraterritorial jurisdiction was abandoned in 1943, foreign rule in China only finally ended with the incorporation of Hong Kong and the small Portuguese territory of Macau into the People's Republic of China in 1997 and 1999 respectively.

China as an imperialist power

Although most discussions of imperialism present China as a victim, this obscures a more complicated picture. While China was under attack in the 19th century by the Europeans, during the 18th century the Qing government had expanded its western borders to include areas such as Xinjiang and Tibet that had historically rarely been under direct Chinese control. Indeed the name Xinjiang itself is Chinese for new border.

The ability of Qing China to project power into Central Asia came about because of two changes, one social and one technological. The social change was that under the Qing dynasty, from 1616, China came under the control of the Manchus who organized their military forces around cavalry which was more suited for power projection than traditional Chinese infantry. The technological change was advances in cannon and artillery which negated the military advantage that the people of the steppe had with their cavalry.

Qing actions in Central Asia were aided by the preference of most local rulers (particularly in Tibet) for the relative light touch of Manchu control over the heavy-handedness of Russia or the British. The Manchus were from Central Asia themselves and ruled China with the support of many people from Mongolia, Tibet and Xinjiang. The Manchu ruling family, like most Mongols, was a supporter of Tibetan Buddhism and so many of the ruling groups were linked by religion. China most of the time had little ambitions to conquer or establish colonies, not even during its golden years during the Tang Dynasty and when it had the world's strongest and biggest fleet during the Ming Dynasty. Rather Chinese immigrated overseas to areas outside the control of their government. For instance numerous southern Chinese emigrants unofficially settled down in Southeast Asia, whose descendants have strong economic influence there today.

Central and Western Asia: The Great Game

Main article: The Great Game Britain, China and Russia were rivals in the theatre of Central and Western Asia. In the late 19th century, Russia took control of large areas of Central Asia, leading to a brief crisis with Britain over Afghanistan in 1885. In Persia (now Iran), both nations set up banks to extend their economic influence. Britain went so far as to invade Tibet, a land under nominal Chinese suzerainty, in 1904, withdrawing when it emerged that Russian influence was insignificant and after a military defeat by one of China's modernized New Armies.

By the Anglo–Russian Entente of 1907, Russia gave up claims to Afghanistan. Chinese suzerainty over Tibet also was recognized by both Russia and Britain, since nominal control by a weak China was preferable to control by either power. Persia was divided into Russian and British spheres of influence and an intervening neutral (free or common) zone. Britain permitted subsequent Russian action (1911) against Persia's nationalist government. After the Russian Revolution, Russia gave up her claim to a sphere of influence, though Soviet involvement persisted alongside Britain's until the 1940s.

In the Middle East, a German company built a railroad from Constantinople to Baghdad and the Persian Gulf. Germany wanted to gain economic control of the region and then move on to Iran and India. This was met with bitter resistance by Britain, Russia, and France who divided the region among themselves.

The Portuguese

The Portuguese, based at Goa and Malacca, built up a maritime empire in the Indian Ocean, meant to monopolize the spice trade. To facilitate China and Japan trade, they established a base at Macao in South China. The Portuguese did not continue to seriously expand in Asia primarily because they had become hugely over-stretched due to the limitations on their colonial expenditure and contemporary naval technology (Both of these factors worked in tandem made running the Empire extremely expensive). The existing Portuguese interests in Asia proved sufficient to finance further colonial expansion and entrenchment in areas regarded as of greater strategic importance in nearer Africa and Brazil. As previously mentioned, they were heavily involved with Japanese trade and the first recorded Westerners to have visited Japan were Portuguese: this contact also introduced Christianity and fire-arms into Japan.

Portuguese maritime supremacy was lost to the Dutch in the 17th century, and with this came serious challenges for the Portuguese. However, they still clung to Macao, which was declared a Portuguese colony after the Opium War, and settled a new colony in Timor Island. It was only after the mid-20th century that the Portuguese began to relinquish their colonies in Asia (Goa was invaded by India in 1962; East-Timor was abandoned in 1975 and was then invaded by Indonesia; Macao was given to the Chinese as per a treaty in 1999).

The Dutch in the East Indies

The Dutch East India Company established its headquarters at Batavia (today Jakarta) on the island of Java to take control of the spice trade. The company colonized the island of Taiwan, unclaimed by China at that time, to facilitate trade with China and Japan. After the Napoleonic Wars, the Dutch concentrated their colonial enterprise in the Dutch East Indies (Indonesia) throughout the 19th century. The Dutch lost their colonial prize in the Indies to the Japanese for much of World War II, and still had to fight Indonesian independence forces after Tōkyō surrendered to the Allies in 1945.

The United States in Asia

The United States took control of the Philippines from the Spanish in 1898 during the Spanish-American War. Philippine resistance led to the Philippine-American War from 1899–1902 and the Moro Rebellion (1902–1913). The Americans only granted the Philippines their independence in 1946.

The US annexed Hawaii in 1893 and gained control over several other islands in the Pacific during World War II.

World War I: Changes in Imperialism

When the Central Powers, which included Germany and Turkey were defeated, major changes were felt around the world. Germany lost all of its colonies, while Turkey gave up her Arab provinces; Syria, Palestine, and Mesopotamia (now Iraq) came under French and British control as League of Nations Mandates. The discovery of oil first in Iran and than in the Arab lands in the interbellum provided a new focus for activity on the part of Britain, France, and the United States.

Japan

Japan started developing imperial ambitions in the late 19th century, ambitions that would one day culminate in the cataclysm of World War II. In contrast to the fate of China, Japan was fortunate to escape the fate of other Asian nations.

The Meiji Restoration of 1868 led to administrative modernization and subsequent rapid economic development. Japan had little natural resources of her own and needed both overseas markets and sources of raw materials, fuelling a drive for imperial conquest which began with the defeat of China in 1895. Taiwan, ceded by the Qing Empire, became the first Japanese colony.

In 1899 Japan won agreement from the great powers' to abandon extra-territoriality, and an alliance with Britain established it in 1902 as an international power. Its spectacular defeat of Russia in 1905 gave it the southern portion of the island of Sakhalin, the former Russian lease of the Liaodong Peninsula with Port Arthur (Lüshunkou), and extensive rights in Manchuria (see the Russo-Japanese War). In 1910, Korea was annexed to the Japanese empire.

Japan was now one of the most powerful forces in the Far East, and in 1914 it entered World War I on the side of Britain, seizing German-occupied Kiaochow and subsequently demanding Chinese acceptance of Japanese political influence and territorial acquisitions (Twenty-One Demands, 1915). Mass protests in Peking in 1919 coupled with Allied (and particularly U.S.) opinion led to Japan's abandonment of most of the demands and Jiaozhou's return (1922) to China.

Japan's rebuff was perceived in Tokyo as only temporary, and in 1931 Japanese army units based in Manchuria seized control of the region; full-scale war with China followed in 1937, drawing Japan toward an overambitious bid for Asian hegemony, which ultimately led to defeat and the loss of all its overseas territories after World War II (see Japanese expansionism and Japanese nationalism).