Vietnam War

|

|

| The Vietnam War | |

|---|---|

| Conflict | Vietnam War, part of the Cold War |

| Date | 1957–1975 |

| Place | Southeast Asia |

| Result | • Capitulation of South Vietnam • Reunification of Vietnam under communist rule |

| Major Combatants | |

| Republic of Vietnam (South Vietnam)  United States of America

| Democratic Republic of Vietnam (North Vietnam) Missing image Flag_of_North_Vietnam.gif Flag of North Vietnam National Liberation Front (Viet Cong) Missing image Viet_cong_flag.gif Flag of the Viet Cong |

| Strength | |

| ~1,200,000 (1968) | ~420,000 (1968) |

| Casualties | |

| KIA: ? Total dead: 287,232 Wounded: 1,496,037 | KIA: ? Total dead: Official Vietnamese estimate: 1,100,000 Wounded: 600,000 |

| Civilian Casualties: c. 2—4 million | |

| Categories | |

| Military history of Australia Military history of New Zealand Military history of the Philippines Military history of South Korea Military history of the Soviet Union Military history of Thailand Military history of the United States Military history of Vietnam | |

The Vietnam War was fought from 1957 to 1975 between Vietnamese nationalist and communist forces and an array of Western and pro-Western forces, most notably the United States. The war was fought to decide whether Vietnam would be unified in accordance with an agreement reached at Geneva in 1954, or would remain indefinitely partitioned into the separate countries of North and South Vietnam. The war ended in 1975 with a communist victory and the unification of the country under a government dominated by the Communist Party of Vietnam. In Vietnam, the conflict is known as the American War (Vietnamese Chiến Tranh Chống Mỹ Cứu Nước, which literally means "War Against the Americans to Save the Nation").

| Contents |

Overview

Time period placement for the Vietnam War is unclear. Some consider the Vietnam War to have begun in 1946 with the French attempt to re-establish control over their colony. This definition comes from those who tend to include the war with France, the war between the two Vietnams after 1954, and the war with the American troops until the fall of Saigon in 1975. Many more people separate the 29-year conflict in Vietnam into two separate wars, First Indochina War which was with the French and the Second Indochina War which was with the Americans. The difficulty in this is establishing a beginning and an end. The fighting with the French was more clear-cut (1946 when the Vietnemese wrote their constitution to 1954 with the Geneva Peace Accord.) The fighting with the Americans was less clear-cut. The American government began funding the French fight in the early 1950s. After the peace agreement, American troops were stationed in South Vietnam. From there on, the American involvement escalated. Many Americans consider the Vietnam War, the conflict between US and NVA troops, not to have begun until 1965 after the Gulf of Tonkin incident, when the US claimed North Vietnamese forces attacked US Navy ships twice. The latter report was later proven to be falsified, although that would not be clear for a while. The war was fought on the ground in South Vietnam and bordering areas of Cambodia and Laos (see Secret War) and in the strategic bombing (see Operation Rolling Thunder) of North Vietnam. For more details of the events during the war, see: Timeline of the Vietnam War. Many experts consider the Vietnam War to just be one frontline in the larger Cold War.

Fighting on one side was a coalition of forces including the Republic of Vietnam (South Vietnam or the "RVN"), the United States, South Korea, Thailand, Australia, New Zealand, and the Philippines. Participation by the South Korean military was financed by the United States, but Australia and New Zealand fully funded their own involvement. Other countries normally allied with the United States in the Cold War, including the United Kingdom and Canada, refused to participate in the coalition, although a few of their citizens volunteered to join the US forces. Canada, in fact, led peace talks between the two countries for years.

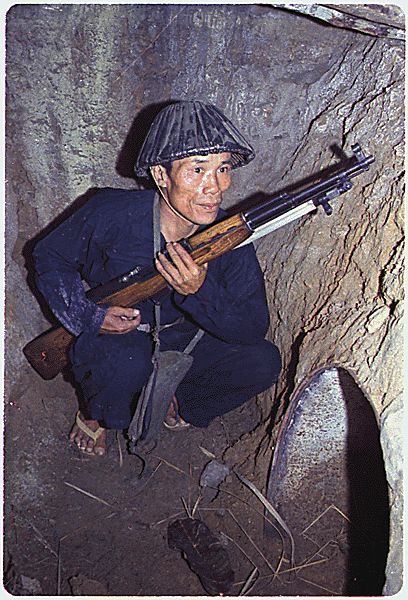

Fighting on the other side was a coalition of forces including the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (North Vietnam) and the National Liberation Front, a South Vietnamese opposition movement with a guerrilla militia known in the Western world as the "Viet Cong". The USSR provided military and financial aid, along with diplomatic support to the North Vietnamese and to the NLF, partly as support against the U.S. and South Vietnamese government and partly as a counter to Chinese influence in the region.

The Vietnam War is classed as the second war of the Indochina Wars and was in many ways a direct successor to the French Indochina War in which the French, with the financial and logistical support of the United States, fought a losing effort to maintain control of her former colony of French Indochina.

France had gained control of Indochina in a series of colonial wars beginning in the 1840s and lasting until the 1880s. During World War II, Vichy France had collaborated with the occupying Imperial Japanese forces. Vietnam was under effective Imperial Japanese control, as well as de facto Japanese administrative control, although the Vichy French continued to serve as the official administrators. After the Japanese surrender, the Vietnamese had hoped to move to formal independence from France. Political events outside Asia, however, dictated that this would not come easily.

On September 2, 1945, Ho Chi Minh organized a ceremony to herald the coming of an independent Vietnam. In his speech, he even cited the American Declaration of Independence, and a band played "The Star Spangled Banner." Ho had hoped that the United States would be his ally in the movement for Vietnamese independence, basing his supposition on the notion that President Franklin Roosevelt had repeatedly spoken against the continuation of European imperialism after the armistice with Germany and Japan.

Early US Indochina Policy

Washington's desire for a more uniform postwar European economy and European cooperation on a variety of other matters, however, proved more important than Roosevelt's call for the dissolution of Europe's empires. France, prompted by nationalists, such as General Charles de Gaulle, demanded a return of its overseas colonies. Since French cooperation was deemed vital in the postwar period, and since successive French governments threatened to become less cooperative in Europe if the United States refused to accede to their demands overseas, Washington committed itself to a policy of supporting the French colonial regime in Indochina. According to Herring (1986, p. 23.), the "French repeatedly warned that they could not furnish troops for European defense without generous American support in Indochina, a ploy Secretary of State Dean Acheson accurately described as 'blackmail'."

Many American foreign policy theorists by the beginning of the 1950s, moreover, had been more or less won over by the twin doctrines of containment, as proposed in 1947 by George Kennan, and the domino theory, which held that if one country "fell" to communism, its neighbors would be soon to follow. The latter of these doctrines often assumed a good deal of vertical unity in international communist movements, directed by Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin and his successors. While this was largely true of European communist parties (with the exception of Yugoslav leader Tito), the situation was somewhat different in Asia.

The internal political climate of the United States also contributed to Washington's commitment in Southeast Asia. The well-known campaign of Senator Joseph McCarthy put considerable pressure on the ruling Democrats to be tougher on communism. Levelling the charge that the Democrats had "sold out" Eastern Europe, in particular Poland, at the Yalta Conference in 1945, and that they were therefore "soft on communism," McCarthy's attacks prompted President Truman to pursue a harder line on international communist movements, in Korea as well as Vietnam.

After taking power in 1953, the Republican administration of President Eisenhower accepted the Indochina policy established by the Truman Administration and its foreign policy corps essentially without modification. Support for the French colonial regime was continued, on the pretense that the French were fighting towards the ultimate independence of Vietnam, as well as the defeat of the communists.

The Rise of Ho Chi Minh and the Viet Minh

On August 13, 1945, the ICP Central Committee held its Ninth Plenum at Tan Trao to prepare an agenda for a National Congress of the Viet Minh a few days later. At the plenum, convened just after the dropping of the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, an order for a general uprising was issued, and a national insurrection committee was established headed by ICP general secretary Truong Chinh (see Development of the Vietnamese Communist Party , ch. 4; Appendix B). On August 16, the Viet Minh National Congress convened at Tan Trao and ratified the Central Committee decision to launch a general uprising. The Congress also elected a National Liberation Committee, headed by Ho Chi Minh (who was gravely ill at the time), to serve as a provisional government. The following day, the Congress, at a ceremony in front of the village dinh, officially adopted the national red flag with a gold star, and Ho read an appeal to the Vietnamese people to rise in revolution.

By the end of the first week following the Tan Trao conference, most of the provincial and district capitals north of Hanoi had fallen to the revolutionary forces. When the news of the Japanese surrender reached Hanoi on August 16, the local Japanese military command turned over its powers to the local Vietnamese authorities. By August 17, Viet Minh units in the Hanoi suburbs had deposed the local administrations and seized the government seals symbolizing political authority. Selfdefense units were set up and armed with guns, knives, and sticks. Meanwhile, Viet Minh-led demonstrations broke out inside Hanoi. The following morning, a member of the Viet Minh Municipal Committee announced to a crowd of 200,000 gathered in Ba Dinh Square that the general uprising had begun. The crowd broke up immediately after that and headed for various key buildings around the city, including the palace, city hall, and police headquarters, where they accepted the surrender of the Japanese and local Vietnamese government forces, mostly without resistance. The Viet Minh sent telegrams throughout Tonkin announcing its victory, and local Viet Minh units were able to take over most of the provincial and district capitals without a struggle. In Annam and Cochinchina, however, the Communist victory was less assured because the ICP in those regions had neither the advantage of long, careful preparation nor an established liberated base area and army. Hue fell in a manner similar to Hanoi, with the takeover first of the surrounding area. Saigon fell on August 25 to the Viet Minh, who organized a nine-member, multiparty Committee of the South, including six members of the Viet Minh, to govern the city. The provinces south and west of Saigon, however, remained in the hands of the Hoa Hao. Although the Hoa Hao and Cao Dai were anti-French, both were more interested in regional autonomy than in communist-led national independence. As a result, clashes between the Hoa Hao and the Viet Minh broke out in the Mekong Delta in September.

Ho Chi Minh moved his headquarters to Hanoi shortly after the Viet Minh takeover of the city. On August 28, the Viet Minh announced the formation of the provisional government of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV) with Ho as president and minister of foreign affairs. Vo Nguyen Giap was named minister of interior and Pham Van Dong minister of finance. In order to broaden support for the new government, several noncommunists were also included. Emperor Bao Dai, whom the communists had forced to abdicate on August 25, was given the position of high counselor to the new government. On September 2, half a million people gathered in Ba Dinh Square to hear Ho read the Vietnamese Declaration of Independence, based on the American Declaration of Independence and the French Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen. After indicting the French colonial record in Vietnam, he closed with an appeal to the victorious Allies to recognize the independence of Vietnam.

Despite the heady days of August, major problems lay ahead for the ICP. Noncommunist political parties, which had been too weak and disorganized to take advantage of the political vacuum left by the fall of the Japanese, began to express opposition to communist control of the new provisional government. Among these parties, the nationalist VNQDD and Viet Nam Phuc Quoc Dong Minh Hoi parties had the benefit of friendship with the Chinese expeditionary forces of Chiang Kai-shek, which began arriving in northern Vietnam in early September. At the Potsdam Conference in July 1945, the Allies had agreed that the Chinese would accept the surrender of the Japanese in Indochina north of the 16?N parallel and the British, south of that line. The Vietnamese nationalists, with the help of Chinese troops, seized some areas north of Hanoi, and the VNQDD subsequently set up an opposition newspaper in Hanoi to denounce "red terror." The communists gave high priority to avoiding clashes with Chinese troops, which soon numbered 180,000. To prevent such encounters, Ho ordered VLA troops to avoid provoking any incidents with the Chinese and agreed to the Chinese demand that the communists negotiate with the Vietnamese nationalist parties. Accordingly, in November 1945, the provisional government began negotiations with the VNQDD and the Viet Nam Phuc Quoc Dong Minh Hoi, both of which initially took a hard line in their demands. The communists resisted, however, and the final agreement called for a provisional coalition government with Ho as president and nationalist leader Nguyen Hai Than as vice president. In the general elections scheduled for early January, 50 of the 350 National Assembly seats were to be reserved for the VNQDD and 20, for Viet Nam Phuc Quoc Dong Minh Hoi, regardless of the results of the balloting.

At the same time, the communists were in a far weaker political position in Cochinchina because they faced competition from the well-organized, economically influential, moderate parties based in Saigon and from the Hoa Hao and Cao Dai in the countryside. Moreover, the commander of the British expeditionary forces, which arrived in early September, was unsympathetic to Vietnamese desires for independence. French troops, released from Japanese prisons and rearmed by the British, provoked incidents and seized control of the city. A general strike called by the Vietnamese led to clashes with the French troops and mob violence in the French sections of the city. Negotiations between the French and the Committee of the South broke down in early October, as French troops began to occupy towns in the Mekong Delta. Plagued by clashes with the religious sects, lack of weapons, and a high desertion rate, the troops of the Viet Minh were driven deep into the delta, forests, and other inaccessible areas of the region.

Meanwhile, in Hanoi, candidates supported by the Viet Minh won 300 seats in the National Assembly in the January 1946 elections. In early March, however, the threat of the imminent arrival of French troops in the north forced Ho to negotiate a compromise with France. Under the terms of the agreement, the French government recognized the DRV as a free state with its own army, legislative body, and financial powers, in return for Hanoi's acceptance of a small French military presence in northern Vietnam and membership in the French Union. Both sides agreed to a plebiscite in Cochinchina. The terms of the accord were generally unpopular with the Vietnamese and were widely viewed as a sell-out of the revolution. Ho, however, foresaw grave danger in refusing to compromise while the country was still in a weakened position. Soon after the agreement was signed, some 15,000 French troops arrived in Tonkin, and both the Vietnamese and the French began to question the terms of the accord. Negotiations to implement the agreement began in late spring at Fontainbleau, near Paris, and dragged on throughout the summer. Ho signed a modus vivendi (temporary agreement), which gave the Vietnamese little more than the promise of negotiation of a final treaty the following January, and returned to Vietnam.

The End of French Involvement

It is generally accepted that the United States funded approximately one-third of the French attempts to retain control of Vietnam, in the face of resistance from the Viet Minh independence movement led by Communist Party leader Ho Chi Minh. The French, however, failing to make headway against Ho and under increasing pressure from Washington to make good on its end of the bargain, adopted tougher measures by 1953. For instance, the so-called Navarre Plan called for a buttressing of the Vietnamese National Guard and the deployment of an additional nine battalions of French troops. The French made a request for $400 million in American assistance, of which $385 million was ultimately given. This discrepancy has often led to the charge that the United States failed to adequately fund French efforts to crush the rebellion early. (Herring, 1986, p. 27) The Navarre Plan ultimately failed to end the fighting, however. After the Viet Minh defeated the French colonial army at the Battle of Dien Bien Phu in 1954, the French military withdrew, and the colony gained independence.

The issue of increasing US involvement in Vietnam was by this point already proving to be divisive in Washington. President Eisenhower, seeing a resurgent isolationism in the Congress, was reluctant to overtly commit US forces to region, even to support the faltering French forces at Dien Bien Phu. On whether to sortie an air strike in support of the French, Eisenhower believed that if it were done, the US would have to deny it forever.

Unwilling to directly support French colonialism, and somewhat disillusioned by the mixed results of American intervention in Korea, Congress instead opted for Secretary of State John Foster Dulles' proposal for "United Action" in Southeast Asia. "United Action" was an outgrowth of the Eisenhower Administration's "New Look" policy, whereby local forces should be called upon for the defense of their territories rather than relying on direct US military involvement. "United Action" called for Vietnamese forces to be responsible for the defense of Vietnam, although with US assistance. The direct results of "United Action" were Washington's tacit acceptance of the upcoming Geneva Accords and the creation of SEATO, a coalition of the United States, Great Britain, France, Australia, New Zealand, the Philippines, Thailand, and Pakistan to draw a firm line against communist expansion and make war in Southeast Asia less likely. The signatories would share the military burdens of protecting Southeast Asia from "indirect aggression." This was certainly more diplomatic than the later more or less unilateral US intervention turned out to be, but it was a stop-gap measure which reflected the widespread opposition of the American people to further involvement in Asia.

Thus, the later ferocity of the conflict was a partial outgrowth of American ambivalence to Vietnam in the 1950s. Hoping to prevent another Korea, the United States ensured that an even worse conflict would ensue. Some argue that had the United States been willing to intervene on behalf of the French at Dien Bien Phu, a French withdrawal could then have been arranged. As Washington was unwilling to support French colonialism, yet still determined to prevent a communist takeover in Vietnam, it instead pursued a middle policy which acquiesced in the creation and entrenchment of strong communist forces in Vietnam, which ultimately proved impossible to defeat.

The Partition of Vietnam and the Diem Government

According to the ensuing Geneva Conference (1954), Vietnam was partitioned, ostensibly temporarily, into a Northern and a Southern zone of Viet-Nam. The former was to be ruled by Ho Chi Minh, while the latter would be under the control of Emperor Bao Dai. In 1955, the South Vietnamese monarchy was abolished and Prime Minister Ngo Dinh Diem became President of a new South Vietnamese republic.

Once again, the geopolitical climate of Europe dictated the flow of events in Vietnam. The French, under increasing domestic pressure, due in part to the escalating Cold War, sought conciliation with the Soviet Union in the wake of Stalin's death in 1953, which had convinced many that a Russian attack on Western Europe was less imminent. As a result, the Soviet Union and communist China were invited to Geneva. Their influence at the conference clearly had a concrete impact in the form of the materialization of Ho's North Vietnam.

The Geneva Conference (1954) specified that elections to unify the country would be scheduled to take place in July, 1956, but such elections were never held. In the context of the Cold War, the United States (under Eisenhower) had begun to view Southeast Asia as a potential key battleground in the greater Cold War, and American policymakers feared that democratic elections would allow communists to influence the South Vietnamese government.

At this point, South Vietnam came under the control of the US-backed Ngo Dinh Diem, an anti-communist exile previously residing in New Jersey. Over French objections, the United States sought to install Diem because he was regarded as a staunch nationalist who could more adequately oversee the construction of a pro-Western South Vietnam than the Emperor, Bao Dai.

Diem's early regime was troubled by the so-called sect crisis of 1955. The Cao Dai and Hoa Hao religious sects were among the most potent political factions in Vietnam in the wake of the partition. They effectively controlled huge rural areas and maintained their own private armies. In addition, the Binh Xuyen, something of a mafia organization, also wielded immense influence and military strength. Their challenge to Diem's fledgling government cast serious doubt on the likelihood of success of the American efforts in Vietnam, and many began to expect an ultimate US withdrawal. Although it initially appeared that Diem would be unable to resist the pressures of these organizations, his startlingly successful (and US-backed) campaigns against them in 1955 prompted a deeper American commitment. Convinced that if Diem could handle the insurgency of the sects he could tackle the Viet Minh, the suddenly enthusiastic support of many Congressional leaders in Washington helped to produce "an American policy reversal of enormous long-range significance." (Herring, 54)

Washington hoped that its influence would be perceived as less overtly colonial than that of the French. Dulles, on the premise that a communist leadership would under no circumstances allow free elections, argued that it was in US interests to allow Diem to hold a rigged referendum ahead of the elections mandated by the Geneva Conference. Given the solvency of the Diem government apparently shown by its victory over the sects, maintaining a strong anti-communist government in Saigon proved more important than adherence to democratic processes. Diem promptly "won" public support in the 1955 referendum, infamously receiving over 600,000 votes from the approximately 400,000 eligible voters in Saigon.

In the hopes of preventing another political crisis akin to China or Korea, the United States lavished support on South Vietnam. Unfortunately, most of the aid proferred was squandered on projects that did little to foster economic development in the South, and did almost nothing for the rural peasantry, which made up about 90% of the population. For instance, the majority of imports were consumer goods, which, paid for by American aid, did much to artificially inflate the standard of living in Saigon, but next to nothing for other areas. Economically, it was a precarious house of cards. At the same time, Diem pursued ruthlessly repressive measures to protect his authority, using his brother Ngo Dinh Nhu to jail or intimidate much of the political opposition, only fostering deeper resentment of what was already an unpopular government.

Diem's RVN government had gained the support of the US to circumvent the scheduled democratic elections, and under Diem's dictatorship, South Vietnam would be free of both socialism, and a democratic process that threatened to irreversibly install it. The North Vietnamese had been winning the public relations battle; it had implemented a massive agricultural reform program which distributed land to peasant farmers, and the people of the South took notice. President Eisenhower noted in his memoirs that if a nation-wide election had been held, the communists would have won. Also, it was said to have been unlikely that the Northern Communists would allow a free election in their half of Vietnam. In the end, neither the US nor the two Vietnams had signed the election clause in the accord. Initially, it appeared as if a partitioned Vietnam would become the norm, similar in nature to the partitioned Korea created years earlier.

The Road to War

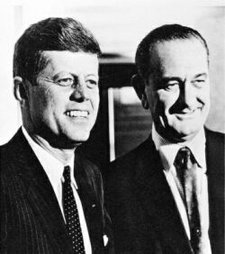

John F. Kennedy and Vietnam

In June 1961, John F. Kennedy met Nikita Khrushchev in Vienna, where Khrushchev sought to bully the young American President into conceding to the Soviets certain key contests, notably Berlin, where large numbers of skilled workers had been escaping to the West. Kennedy left the meeting agitated, and quickly determined that Khrushchev's attitude towards him would make an armed conflict virtually unavoidable in the near future. Kennedy and his advisers soon decided that any such conflicts had better follow the Korea model, being confined to conventional weaponry, through proxy parties, as a way to mitigate the threat of direct nuclear war between the two superpowers. It was decided that the most likely theatre for such a conflict would be in Southeast Asia. By the political calculations of his administration, the U.S. had to work quickly to create a "valve" to release any built-up political pressures.

The North knew well that the South was prepared to vote for a communist government. The U.S. cared little for Diem, but forged its alliance with his government out of fear that an easy communist victory would only bolster the perceived bravado that Khrushchev had shown to Kennedy at Vienna. The U.S. fatefully decided that an immediate stand against Soviet expansion was both prudent and necessary, regardless of the human cost (The Red Scare).

The Kennedy administration, in terms of foreign policy, never fully emerged from the shadow of Truman, in the sense that the domestic crisis unleashed by the "failure" of the last Democratic administration to prevent the fall of China in 1949 prompted Kennedy to resist as strongly as possible any potential gains by communist movements. In 1961, moreover, Kennedy found himself faced with a tripartite crisis that appeared to him very similar to that faced by Truman in 1949-1950. In that year, Truman sought to counterbalance the fall of China and the detonation of the first Soviet atomic bomb with a firm stand in Korea. From Kennedy's perspective, 1961 had already seen the failure of the Bay of Pigs invasion, the construction of the Berlin Wall, and a negotiated settlement between the pro-Western government of Laos and the Pathet Lao communist movement. Fearing that another failure on the part of the United States to stop communist expansion would fatally damage his and Washington's reputation, Kennedy placed a new emphasis on preventing a communist victory in Vietnam.

Eventually, the Kennedy administration grew increasingly frustrated with Diem. In an embarrassing incident that was widely reported in the US press, Diem's forces launched a violent crackdown on Buddhist monks. Since Vietnam was a predominantly Buddhist nation while Diem and much of the ruling structure of South Vietnam was Roman Catholic, this action was viewed as further proof that Diem was completely out of touch with his people. US messages were sent to South Vietnamese generals encouraging them to act against Diem's excesses. Though there is some debate as to whether or not this was Kennedy's intention, the South Vietnamese military interpreted these messages as a call to arms, and staged a violent coup d'鴡t, overthrowing and killing Diem on November 1, 1963.

Far from uniting the country under new leadership, the death of Diem made the South even more unstable. The new military rulers were very inexperienced in political matters, and were unable to provide the strong central authority of Diem's rule. Coups and counter-coups plagued the country, and though the immediate aftermath of Diem's death took much of the impetus away from the NLF, since it no longer had the person of Diem around which to rally resentment, Hanoi quickly stepped up its efforts to escalate the war against the South in order to exploit the vacuum.

Three weeks after Diem's death, Kennedy himself was assassinated, and Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson was suddenly thrust into the war's leadership role. Newly sworn-in President Johnson confirmed on November 24, 1963 that the United States intended to continue supporting South Vietnam militarily and economically.

Combatants in the war

In major combat there were, depending upon one's point of view, two to four major combatant organizations; the four being the United States armed forces and allied forces; the Army of the Republic of Viet Nam (ARVN—the South Vietnamese Army, pronounced Arvin, leading to the pejorative Marvin The Arvin); the NLF(Vietcong), a group of indigenous South Vietnamese guerilla fighters; and the People's Army of Viet Nam (PAVN—the North Vietnamese Army, pronounced Pahvin).

Arguments over which of these four were the actual combatants was a major political focus of the war. The U.S. sought to depict the war as one between ARVN defenders with U.S. help against PAVN forces, thus depicting the NLF a puppet or shadow army and the war as a South Vietnamese defense against North Vietnamese aggression.

The North Vietnamese portrayed the conflict as one between the indigenous South Vietnamese NLF and the United States, with the noncombat support of North Vietnam and its allies. This view held ARVN to be a puppet of the U.S.

These conflicting propaganda stances were later played out in early peace talks in which arguments were made over "the shape of the [negotiating] table" in which each side sought to depict itself as two distinct entities opposing a single entity, ignoring its "puppet".

Escalation

U.S. involvement in the war followed a strategy of escalation, using the analogy of an escalator rising slowly but steadily to increase war pressure on the enemy, as opposed to the traditional declaration of war with the usual massive attack using all available means to secure victory.

Under escalation, U.S. involvement increased over a period of years, beginning with the deployment of non-combatant military advisors to the South Vietnamese army, to use of special forces for commando-style operations, to introduction of regular troops whose purpose was to be defensive only, to using regular troops in offensive combat. Once U.S. troops were engaged in active combat, escalation shifted to the addition of increasing numbers of U.S. troops.

The policy of escalation helped complicate the ambiguous legal status for the war. Since the U.S. had pre-existing treaty agreements with the Republic of Viet Nam, each escalation was presented as simply another step in helping an ally resist Communist aggression. The U.S. Congress continued to vote appropriations for war operations, and the Johnson Administration claimed these actions as a proxy, along with Tonkin, for the Constitutionally mandated requirement that Congress retain war power.

By keeping its involvement limited, it was hoped, the United States could buttress the government of South Vietnam without provoking a major response from China or the Soviet Union, as had happened the previous decade in Korea. Johnson attempted to tread a line between keeping Beijing and Moscow out of the war while retaining an independent, pro-Western South Vietnam-seen as crucial to US prestige threatened by Soviet actions, especially in Cuba, but also in Europe and elsewhere. In this sense, Johnson saw Vietnam just as Kennedy had: the American response to the Berlin Wall and the Cuban Missile Crisis.

Escalation caused serious friction between the American armed services and the civilian authorities in Washington. Military officials such as General William Westmoreland resented the Johnson Administration's restraints on their operations, yet at the same time were wary of speaking out, lest they suffer the same fate as General Douglas MacArthur, who had been dismissed by Truman for insubordination during the Korean War.

In U.S. political debate, the advantage of escalation to those who wanted to be engaged in the war was that no individual instance of escalation dramatically increased the level of U.S. involvement. The U.S. populace was led to believe that the most recent escalation would be sufficient to "win the war" and therefore would be the last. This theory, combined with ready availability of conscripted troops, reduced grassroots political opposition to the war until 1968, when the Johnson Administration considered increasing the troop levels from approximately 550,000 in-country to about 700,000. This was the "straw" that broke the back of U.S. support for the war. The troop increase was abandoned and by the end of 1969, under the new administration of Richard M. Nixon, U.S. troop levels had been reduced by 60,000 from their wartime peak.

Increasing US involvement to 1964

US involvement in the war was a gradual process. This involvement increased over the years under three U.S. Presidents, both Democratic and Republican (successively Eisenhower-R, Kennedy-D and Johnson-D, and was sustained for additional years in the administration of Richard Nixon-R), despite warnings by the US military leadership against a major ground war in Asia. Though actions under the administrations of Eisenhower and Kennedy are considered to have cast the die for the future conflict, it was Johnson who expanded and transformed the engagement into a distinctly U.S. operation, a policy which eventually led to opposition within his own party that convinced him not to seek a second term in 1968 after internal polling showed the depth of public doubt and anger.

There was never a formal declaration of war but there were a series of presidential decisions that increased the number of "military advisors" and then active combatants in the region.

In the campaign for the presidency in 1960, the perceived Soviet threat and slippage in U.S. standing in the world was a prominent issue and Kennedy made erosion of the U.S. position in the world a major campaign issue. The Pentagon Papers (Chapter I, "The Kennedy Commitments and Programs, 1961,") elaborated on this point.

- A further element of the Soviet problem impinged directly on Vietnam. The new Administration, even before taking office, was inclined to believe that unconventional warfare was likely to be terrifically important in the 1960s. In January, 1961, Khrushchev seconded that view with his speech pledging Soviet support to "wars of national liberation". Vietnam was where such a war was actually going on. Indeed, since the war in Laos had moved far beyond the insurgency stage, Vietnam was the only place in the world where the Administration faced a well-developed Communist effort to topple a pro-Western government with an externally-aided pro-communist insurgency.

The prominent linguist and leftist anti-war critic Noam Chomsky claims that Kennedy ordered the US Air Force to start bombing South Vietnam as early as 1962, using South Vietnamese aircraft markings to disguise US involvement. He also accuses Kennedy of authorizing the use of napalm, along with other crop destruction programs at this earlier date, rather than as a later part of the larger war. The traditional view claims that "actual increased U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War" didn't occur until 1964.

The program of covert GVN (South Vietnamese) operations was designed to impose "progressively escalating pressure" upon the North, and initiated on a small and essentially ineffective scale in February 1964, according to standard sources. The active U.S. role in the few covert operations that were carried out was limited essentially to planning, equipping, and training of the GVN forces involved, but U.S. responsibility for the launching and conduct of these activities was unequivocal and carried with it an implicit symbolic and psychological intensification of the U.S. commitment.

American Intervention

Johnson and the Gulf of Tonkin

Johnson raised the level of U.S. involvement on July 27, 1964 when 5,000 additional US military advisors were ordered to South Vietnam which brought the total number of US forces in Vietnam to 21,000.

On July 31, 1964, the American destroyer USS Maddox, continued a reconnaissance mission in the Gulf of Tonkin well offshore in international waters, a mission that had been suspended for six months. Some critics of President Lyndon Johnson say the purpose of the mission was to provoke a reaction from North Vietnamese coastal defense forces as a pretext for a wider war. Responding to an attack, and with the help of air support from the nearby carrier USS Ticonderoga, Maddox destroyed one North Vietnamese torpedo-boat and damaged two others. Maddox, suffering only superficial damage by a single 14.5-millimeter machine gun bullet, retired to South Vietnamese waters, where she was joined by USS C. Turner Joy.

On August 3, GVN again attacked North Vietnam; the Rhon River estuary and the Vinh Sonh radar installation were bombarded under cover of darkness.

On August 4, a new DESOTO patrol to the North Vietnam coast was launched, with Maddox and C. Turner Joy. The latter got radar signals later claimed to be another attack by the North Vietnamese. For some two hours the ships fired on radar targets and maneuvered vigorously amid electronic and visual reports of torpedoes. Later, Captain John J. Herrick admitted that it was nothing more than an "overeager sonarman" who "was hearing ship's own propeller beat". This was not, however, clear at the time. In fact, it was later speculated that Johnson concocted the entire Gulf of Tonkin story. There was no alleged torpedo attack, and Johnson required these attacks to win approval of the Senate to intensify American attacks in Vietnam.

The U.S. Senate then approved the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution on 7 August 1964, which gave broad support to President Johnson to escalate U.S. involvement in the war "as the President shall determine". In a televised address Johnson claimed that "the challenge that we face in South-East Asia today is the same challenge that we have faced with courage and that we have met with strength in Greece and Turkey, in Berlin and Korea, in Lebanon and in Cuba," a dangerous misreading of the politics of the Vietnamese conflict in some people's minds. National Security Council members, including Robert McNamara, Dean Rusk, and Maxwell Taylor agreed on November 28, 1964 to recommend that President Johnson adopt a plan for a two-stage escalation of bombing in North Vietnam.

Operation Rolling Thunder

Operation Rolling Thunder was the code name for the non-stop, but often interrupted bombing raids in North Vietnam conducted by the United States armed forces during the Vietnam War. Its purpose was to destroy the will of the North Vietnamese to fight, to destroy industrial bases and air defenses (SAMs), and to stop the flow of men and supplies down the Ho Chi Minh Trail.

Beginning in the early 1960's, communist North Vietnam (The Democratic Republic of Vietnam, or DRV) began sending arms and reinforcements to the guerrillas of the National Liberation Front (NLF) fighting a war of reunification in South Vietnam. To combat the NLF and shore up the regime in the south, the United States sent advisors, supplies and combat troops. A war escalated that would see American soldiers engaging NLF insurgents and North Vietnamese regular troops in the field.

The supply lines for the war ran south across the demilitarized zone (DMZ) separating North and South Vietnam, or via Laos and Cambodia along the infamous ‘Ho Chi Minh Trail’. The source of these supplies was the People’s Republic of China and the Soviet Union. The road and rail network of the north was vital for transshipping material south. The hub of this network was the national capital, Hanoi.

In August 1964, the ‘Gulf of Tonkin Incident’, a skirmish between DRV and United States Navy ships, gave the US a pretext to launch air strikes against the North. The objective, outlined by President Lyndon B. Johnson, was to discourage further "Communist aggression" by launching punitive attacks against the DRV.

In late 1964 the Joint Chiefs of Staff drew up a list of targets to be destroyed as part of a coordinated interdiction air campaign against the North’s supply network. Bridges, rail yards, docks, barracks and supply dumps would be targeted. However, President Johnson feared that direct intervention by the Chinese or Russians could trigger a world war and refused to authorize an unrestricted bombing campaign. Instead, the attacks would be limited to targets cleared by the President and his Secretary of Defense, Robert S. McNamara.

Beginning in 1965, Rolling Thunder was a sustained bombing campaign against North Vietnam. In the February of 1965, Viet Cong guerrillas attacked an American air base at Pleiku, South Vietnam. President Johnson immediately ordered retaliatory bombing raids against military installations in North Vietnam. Early missions were against the south of the DRV, where the bulk of ground forces and supply dumps were located. Large-scale air strikes were launched on depots, bases and supply targets, but the majority of operations were “armed reconnaissance” missions in which small formations of aircraft patrolled highways and railroads and rivers, attacking targets of opportunity.

Afraid the war might escalate out of hand, Johnson and McNamara micromanaged the bombing campaign from Washington. Rules of engagement were imposed to limit civilian casualties or attacks on other nationals, such as the Eastern Bloc-crewed supply ships in Haiphong harbor or the Soviet and Chinese advisors helping train the Vietnamese military.

However, the American policy of ‘graduated response’ – slowly ramping up pressure on the DRV leadership – meant that more targets became available to airmen to bomb. The bombing moved progressively northwards toward Hanoi. Exclusion zones were maintained around Hanoi and Haiphong to keep bombers away from the population centers, but eventually raids would be authorized even into these sanctuaries.

To keep the United States Air Force and Navy out of each other’s way the DRV was divided into air zones called ‘Route Packages’ (RPs), each assigned to a service. The area around Hanoi included Route Packages 5 and 6a (the USAF’s responsibility) and 4 and 6b (the USN’s). Strikes into RP 6a or 6b were reckoned to be the toughest of all. The Vietnamese, with Soviet and Chinese help, had built a formidable air defense system there. Initially this consisted of anti-aircraft artillery (AAA) and MiG fighter jets, but from mid-1965 this was supplemented by surface-to-air missiles (SAMs). A radar net now covered the country that could track incoming US raids and allocate SAMs or MiGs to attack them.

To survive in this lethal air defense zone the Americans adopted special tactics. Large-scale raids were assigned support aircraft to keep the bombers safe. These would include fighters to keep the MiGs away, jamming aircraft to degrade enemy radars, and ‘Iron Hand’ fighter-bombers to hunt down SAMs and suppress AAA. New electronics countermeasures devices were hurriedly deployed to protect aircraft from missile attacks.

By 1966 the air war in the higher Route Packages was getting hotter. Though most of the casualties came from AAA, there were an increasing number of encounters with SAMs and MiGs. MiGs were a particular problem because the Americans’ poor radar coverage of the Hanoi region allowed obsolete jets such as the MiG-17 to get the jump on them. Airborne Early Warning aircraft had great trouble detecting MiGs at very low altitude.

Most of the USAF raids against the North came out of bases in Thailand. They would refuel over Laos before flying onto their targets. Sometimes the Americans would fly low and use prominent terrain features such as Thud Ridge to mask them from radar as they approached. After attacking the target – usually by dive-bombing – the raid would either head directly back to Thailand or exit over the relatively safe waters of the Gulf of Tonkin.

Navy raids would be launched from TaskForce 77’s carriers cruising on Yankee Station. The complement of a carrier air wing was needed to form an ‘Alpha Strike’. The Navy aircraft would usually take the shortest way into and out from the target.

Bombing halts became a feature of the war. Some of these were politically enforced, as President Johnson tried a ‘carrot and stick’ approach to coax the DRV into a peace agreement. Others were the fault of the weather that for six months a year made bombing near impossible. Attempts were made to overcome the weather by developing blind bombing techniques using radar or radio navigation systems, but at best they generated mediocre results and were often useless. 1967 saw America’s most intense and sustained attempt to force the Vietnamese into peace talks. Almost all the Joint Chiefs’ target list was made available to be attacked, and even airfields – previously off-limits – came in for a pasting. Only the center of Hanoi (nicknamed ‘Downtown’ after the Petula Clark song) and Haiphong harbor remained safe from harm. The Vietnamese reacted by becoming more aggressive with their MiGs and using AAA and SAM to rack up an impressive tally of US aircraft.

After two years of bombardment the Vietnamese were well equipped to handle US raids, having dispersed their supplies and developed the means to repair and rebuild the supply network after the raids had passed. Their strategy was longsighted. They did not have to defeat the Americans, merely absorb the punishment and outlast them.

By 1968 McNamara had become convinced that airpower could not win the war. In spite of the air campaign the Tet New Year holiday saw Hanoi and the NLF mount an offensive in the south. The Tet Offensive was a military disaster for the North and their NLF allies, but it still broke the will of the American leadership. Hoping that Hanoi would enter into peace talks, President Johnson offered a bombing halt. The communists, licking their wounds after Tet, agreed to talks and the Rolling Thunder campaign came to an end.

U.S. Forces Committed

In February of 1965 the U.S. base at Pleiku was attacked twice killing over a dozen Americans. This provoked the reprisal airstrikes of Operation Flaming Dart in North Vietnam. It was the first time an American airstrike was launched because its forces had been attacked in South Vietnam. That same month the U.S. began independent airstrikes in the South. An American HAWK team was sent to Da Nang, a vulnerable airbase if Hanoi intended to bomb it. One result of Operation Flaming Dart was the shipment of anti-aircraft missiles to North Vietnam which began in a few weeks from the Soviet Union.

On March 8, 1965, 3,500 United States Marines became the first American combat troops to land in South Vietnam, adding to the 25,000 US military advisers already in place. The air war escalated as well; on July 24, 1965, four F-4C Phantoms escorting a bombing raid at Kang Chi became the targets of antiaircraft missiles in the first such attack against American planes in the war. One plane was shot down and the other three sustained damage. Four days later Johnson announced another order that increased the number of US troops in Vietnam from 75,000 to 125,000. The day after that, July 29, the first 4,000 101st Airborne Division paratroopers arrived in Vietnam, landing at Cam Ranh Bay.

Then on August 18, 1965, Operation Starlite began as the first major American ground battle of the war when 5,500 US Marines destroyed a NLF stronghold on the Van Tuong peninsula in Quang Ngai Province. The Marines were tipped-off by a NLF deserter who said that there was an attack planned against the US base at Chu Lai. The NVA learned from their defeat and tried to avoid fighting a US-style war from then on.

The Pentagon told President Johnson on November 27, 1965 that if planned major sweep operations needed to neutralize NLF forces during the next year were to succeed, the number of American troops in Vietnam needed to be increased from 120,000 to 400,000. By the end of 1965, 184,000 US troops were in Vietnam. In February 1966 there was a meeting between the commander of the U.S. effort, head of the Military Assistance Command, Vietnam General William Westmoreland and Johnson in Honolulu. Westmoreland argued that the US presence had prevented a defeat but that more troops were needed to take the offensive, he claimed that an immediate increase could lead to the "cross-over point" in Vietcong and NVA casualties being reached in early 1967. Johnson authorized an increase in troop numbers to 429,000 by August 1966.

On 12 October 1967 US Secretary of State Dean Rusk stated during a news conference that proposals by the U.S. Congress for peace initiatives were futile because of North Vietnam's opposition. Johnson then held a secret meeting with a group of the nation's most prestigious leaders ("the Wise Men") on November 2 and asked them to suggest ways to unite the American people behind the war effort. They concluded that the American people should be given more optimistic reports on the progress of the war. Then based on reports he was given on November 13, Johnson told his nation on November 17 that, while much remained to be done, "We are inflicting greater losses than we're taking...We are making progress." Following up on this, General William Westmoreland on November 21 told news reporters: "I am absolutely certain that whereas in 1965 the enemy was winning, today he is certainly losing." Two months later the Tet Offensive made both men regret their words.

The war saw some incredible feats of human bravery perhaps the most spectacular of all was he story of two young men caught in the conflict. Nick Burks and Rory Trevis survived a total of 6 tours of duty, in one they spent several weeks lost in the jungle fighting the NVA with makeshift weapons and surviving off what the jungle could provide.

The Tet Offensive

Continued escalation of American military involvement came as the Johnson administration and Westmoreland repeatedly assured the American public that the next round of troop increases would bring victory. The American public's faith in the "light at the end of the tunnel" was shattered, however, on January 30, 1968, when the enemy, supposedly on the verge of collapse, mounted the Tet Offensive (named after Tet Nguyen Dan, the lunar new year festival which is the most important Vietnamese holiday) in South Vietnam, in which nearly every major city in South Vietnam was attacked. During the temporary Communist occupation of Hue, 3,000 civilians were killed and buried in a mass grave, all of them executed by the Communists, and many were apparently beaten with shovels. This was the worst single massacre against civilians in the war. Although neither of these offensives accomplished any military objectives, the surprising capacity of an enemy that was supposedly on the verge of collapse to even launch such an offensive convinced many Americans that victory was impossible. There was an increasing sense among many people that the government was misleading the American people about a war without a clear beginning or end. When General Westmoreland called for still more troops to be sent to Vietnam, Clark Clifford, a member of Johnson's own cabinet, came out against the war.

Tet Aftermath

Soon after Tet, Westmoreland was replaced by his deputy, General Creighton W. Abrams. Abrams pursued a very different approach to Westmoreland, favoring more openness with the media, less indiscriminate use of airstrikes and heavy artillery, elimination of bodycount as the key indicator of battlefield success, and more meaningful co-operation with ARVN forces. His strategy, although yielding positive results, came too late to sway a domestic US public opinion that was already solidifying against the war.

Facing a troop shortage, on October 14, 1968 the United States Department of Defense announced that the United States Army and Marines would be sending about 24,000 troops back to Vietnam for involuntary second tours. Two weeks later on October 31, citing progress with the Paris peace talks, US President Lyndon B. Johnson announced what became known as the October surprise when he ordered a complete cessation of "all air, naval, and artillery bombardment of North Vietnam" effective November 1. Peace talks eventually broke down, however, and one year later, on November 3, 1969, then President Richard M. Nixon addressed the nation on television and radio asking the "silent majority" to join him in solidarity on the Vietnam War effort and to support his policies.

The credibility of the government suffered when the New York Times, and later the Washington Post and other newspapers, published the Pentagon Papers. It was a top-secret historical study, contracted by the Pentagon, about the war, that showed how the government was misleading the US public, in all stages of the war, including the secret support of the French in the first Vietnam War.

Opposition to the war

Main article: Opposition to the Vietnam War

TrangBang.jpg

Small scale opposition to the war began in 1964 on college campuses. This was happening during a time of unprecedented leftist student activism, and of the arrival at college age of the demographically significant Baby Boomers. Growing opposition to the war is attributable in part to the much greater access to information about the war available to college age Americans compared with previous generations because of extensive television news coverage.

Thousands of young American men chose exile in Canada or Sweden rather than risk conscription. At that time, only a fraction of all men of draft age were actually conscripted; and most of those subjected to the draft were too young to vote or drink in most states, the Selective Service System office ("Draft Board") in each locality had broad discretion on whom to draft and whom to exempt where there was no clear guideline for exemption. The charges of unfairness led to the institution of a draft lottery for the year 1970 in which a young man's birthday determined his relative risk of being drafted (September 14 was the birthday at the top of the draft list for 1970; the following year July 9 held this distinction). The image of young people being forced to risk their lives in the military but not allowed to vote or drink also successfully pressured legislators to lower the voting age nationally and the drinking age in many states.

In order to gain an exemption or deferment many men obtained student deferments by attending college, though they would have to remain in college until their 26th birthday to be certain of avoiding the draft. Some got married, which remained an exemption throughout the war. Some men found sympathetic doctors who would claim a medical basis for applying for a 4F (medically unfit) exemption, though Army doctors could and did make their own judgments. Still others joined the National Guard or entered the Peace Corps as a way of avoiding Vietnam. All of these issues raised concerns about the fairness of who got selected for involuntary service, since it was often the poor or those without connections who were drafted. Ironically, in light of modern political issues, a certain exemption was a convincing claim of homosexuality, but very few men attempted this because of the stigma involved.

The draft itself also initiated protests when on October 15, 1965 the student-run National Coordinating Committee to End the War in Vietnam staged the first public burning of a draft card in the United States. The first draft lottery since World War II in the United States was held on 1 December 1969 and was met with large protests and a great deal of controversy; statistical analysis indicated that the methodology of the lotteries unintentionally disadvantaged men with late year birthdays. [1] (http://www.amstat.org/publications/jse/v5n2/datasets.starr.html) This issue was treated at length in a 4 January 1970 New York Times article titled "Statisticians Charge Draft Lottery Was Not Random".

Even many of those who never received a deferment or exemption never served, simply because the pool of eligible men was so huge compared to the number required for service, that the draft boards never got around to drafting them when a new crop of men became available (until 1969) or because they had high lottery numbers (1970 and later).

The U.S. people became polarized over the war. Many supporters of the war argued for what was known as the Domino Theory, which held that if the South fell to communist guerillas, other nations, primarily in Southeast Asia, would succumb in short succession, much like falling dominoes. Military critics of the war pointed out that the conflict was political and that the military mission lacked clear objectives. Civilian critics of the war argued that the government of South Vietnam lacked political legitimacy, or that support for the war was immoral. President Johnson's undersecretary of state, George Ball, was one of the lone voices in his administration advising against war in Vietnam.

Gruesome images of two anti-war activists that set themselves on fire in November 1965 provided iconic images of how strongly some people felt that the war was immoral. On November 2 32-year-old Quaker member Norman Morrison set himself on fire in front of The Pentagon and, on November 9, 22-year old Catholic Worker Movement member Roger Allen LaPorte did the same thing in front of the United Nations building. Both protests were conscious imitations of earlier (and ongoing) Buddhist protests in South Vietnam itself.

The growing anti-war movement alarmed many in the US government. On August 16, 1966 the House Un-American Activities Committee began investigations of Americans who were suspected of aiding the NLF, with the intent to introduce legislation making these activities illegal. Anti-war demonstrators disrupted the meeting and 50 were arrested.

On 1 February 1968, a suspected NLF officer was summarily executed by General Nguyen Ngoc Loan, a South Vietnamese National Police Chief. Loan shot the suspect in the head on a public street in front of journalists. The execution was filmed and photographed and provided another iconic image that helped sway public opinion in the United States against the war. Photographs do not tell the whole story, Lem was captured near the site of a ditch holding as many as thirty-four bound and shot bodies of police and their relatives, some of whom were the families of General Loan's deputy and close friend.

Nguyen.jpg

On 15 October 1969, hundreds of thousands of people took part in National Moratorium antiwar demonstrations across the United States; the demonstrations prompted many workers to call in sick from their jobs and adolescents nationwide engaged in truancy from school - although the proportion of individuals doing either who actually participated in the demonstrations is in doubt. A second round of "Moratorium" demonstrations was held on November 15, but was less well-attended.

Despite the increasingly depressing news on the war, many Americans continued to support President Johnson's endeavors. Aside from the domino theory mentioned above, there was a feeling that the goal of preventing a communist takeover of a pro-Western government in South Vietnam was a noble objective. Many Americans were also concerned about saving face in the event of disengaging from the war or, as President Richard M. Nixon later put it, "achieving Peace with Honor". In addition, instances of Viet Cong atrocities were widely reported, most notably in an article that appeared in Reader's Digest in 1968 entitled The Blood-Red Hands of Ho Chi Minh.

However, anti-war feelings also began to rise. Many Americans opposed the war on moral grounds, seeing it as a destructive war against Vietnamese independence, or as intervention in a foreign civil war; others opposed it because they felt it lacked clear objectives and appeared to be unwinnable. Some anti-war activists were themselves Vietnam Veterans, as evidenced by the organization Vietnam Veterans Against the War. Some of the Americans opposed to the Vietnam War, as for instance Jane Fonda, stressed their support for ordinary Vietnamese civilians struck by a war beyond their influence. The anti-war sentiments gave reason to a perception among returning soldiers of being spat on.

In 1968, President Lyndon Johnson began his re-election campaign. A member of his own party, Eugene McCarthy, ran against him for the nomination on an antiwar platform. McCarthy did not win the first primary election in New Hampshire, but he did surprisingly well against an incumbent. The resulting blow to the Johnson campaign, taken together with other factors, led the President to make a surprise announcement in a March 31 televised speech that he was pulling out of the race. He also announced the initiation of the Paris Peace Talks with Vietnam in that speech. Then, on August 4, 1969, US representative Henry Kissinger and North Vietnamese representative Xuan Thuy began secret peace negotiations at the apartment of French intermediary Jean Sainteny in Paris. The negotiations eventually failed, however.

Seizing the opportunity caused by Johnson's departure from the race, Robert Kennedy then joined in and ran for the nomination on an antiwar platform. Johnson's vice president, Hubert Humphrey, also ran for the nomination, promising to continue to support the South Vietnamese government.

Kennedy was assassinated that summer, and Eugene McCarthy was unable to overcome Humphrey's support within the party elite. Humphrey won the nomination of his party, and ran against Richard Nixon in the general election. During the campaign, Nixon has been said to have claimed knowledge of a secret plan to end the war; actually, a plan was not formed until after his inauguration. It was thought to have occurred because at one point, his opponent for G.O.P. nomination, Gov. George Romney of Michigan, asked him "Where is your secret plan?"

Opposition to the Vietnam War in Australia followed along similar lines to the United States, particularly with opposition to conscription. While Australian disengagement began in 1970 under John Gorton, it was not until the election of Gough Whitlam in 1972 that conscription ended.

Pacification and the "Hearts and Minds"

The U.S. realized that the South Vietnamese government needed a solid base of popular support if it was to survive the insurgency. In order to pursue this goal of "winning the hearts and minds" of the Vietnamese people, units of the United States Army, referred to as "Civil Affairs" units, were extensively utilized for the first time for this purpose since World War II.

Civil Affairs units, while remaining armed and under direct military control, engaged in what came to be known as "nation building": constructing (or reconstructing) schools, public buildings, roads and other physical infrastructure; conducting medical programs for civilians who had no access to medical facilities; facilitating cooperation among local civilian leaders; conducting hygiene and other training for civilians; and similar activities.

This policy of attempting to win the "Hearts and Minds" of the Vietnamese people, however, often was at odds with other aspects of the war which served to antagonize many Vietnamese civilians. These policies included the emphasis on "body count" as a way of measuring military success on the battlefield, the accidental bombing of villages (symbolized by journalist Peter Arnett's famous quote, "it was necessary to destroy the village in order to save it"), and the killing of civilians in such incidents as the My Lai massacre. In 1974 the documentary "Hearts and Minds" sought to portray the devastation the war was causing to the South Vietnamese people, and won an Academy Award for best documentary amid considerable controversy. The South Vietnamese government also antagonized many of its citizens with its suppression of political opposition, through such measures as holding large numbers of political prisoners, torturing political opponents, and holding a one-man election for President in 1971. Despite this, the government captured a large percentage of the votes of the large percentage of the Vietnamese that participated.

"Vietnamization"

Nixon was elected President and began his policy of slow disengagement from the war. The goal was to gradually build up the South Vietnamese Army so that it could fight the war on its own. This policy became the cornerstone of the so-called "Nixon Doctrine". As applied to Vietnam, the doctrine was called "Vietnamization". The stated goal of Vietnamization was to enable the South Vietnamese army to increasingly hold its own against the NLF and the North Vietnamese Army. The unstated goal of Vietnamization was that the primary burden of combat would be returned to ARVN troops and thereby lessen domestic opposition to the war in the U.S.

During this period, the United States conducted a gradual troop withdrawal from Vietnam. Nixon continued to use air power to bomb the enemy, along with an American troop incursion in Cambodia. Ultimately more bombs were dropped under the Nixon Presidency than under Johnson's, while American troop deaths started to drop significantly. The Nixon administration was determined to remove American troops from the theater while not destabilizing the defensive efforts of South Vietnam.

Many significant gains in the war were made under the Nixon administration, however. One particularly significant achievement was the weakening of support that the North Vietnamese army received from the Soviet Union and People's Republic of China. One of Nixon's main foreign policy goals had been the achievement of a "breakthrough" in relations between the two nations, in terms of creating a new spirit of cooperation. To a large extent this was achieved. China and the USSR had been the principal backers of the North Vietnamese army through large amounts of military and financial support. The eagerness of both nations to improve their own US relations in the face of a widening breakdown of the inter-Communist alliance led to the reduction of their aid to North Vietnam.

The morality of US conduct of the war continued to be an issue under the Nixon Presidency. In 1969, American investigative journalist Seymour Hersh exposed the My Lai massacre and its cover-up, for which he received the Pulitzer Prize for International Reporting. It came to light that Lt. William Calley, a platoon leader in Vietnam, had led a massacre of several hundred Vietnamese civilians, including women, babies, and the elderly, at My Lai a year before. The massacre was only stopped after two American soldiers in a helicopter spotted the carnage and intervened to prevent their fellow Americans from killing any more civilians. Although many were appalled by the wholesale slaughter at My Lai, Calley was given a life sentence after his court-martial in 1970, and was later pardoned by President Nixon. Cover-ups or soft treatments of American war crimes also happened in other cases, e.g. as revealed by the Pulitzer Prize winning article series about the Tiger Force by the Toledo Blade in 2003. But My Lai was the worst.

In 1970, Prince Sihanouk was deposed by Lon Nol in Cambodia, who became the chief of state. The Khemer Rouge guerillas with North Vietnamese backing began to attack the new regime. Nixon ordered a military incursion into Cambodia in order to destroy NLF sanctuaries bordering on South Vietnam and protect the fragile Cambodian government. This action prompted even more protests on American college campuses. Several students were shot and killed by National Guard troops during demonstrations at Kent State.

One effect of the incursion was to push communist forces deeper into Cambodia, which destabilized the country and in turn may have encouraged the rise of the Khmer Rouge, who seized power in 1975. The goal of the attacks, however, was to bring the North Vietnamese negotiators back to the table with some flexibility in their demands that the South Vietnamese government be overthrown as part of the agreement. It was also alleged that American and South Vietnamese casualty rates were reduced by the destruction of military supplies the communists had been storing in Cambodia. All U.S. forces left Cambodia on June 30.

In an effort to help assuage growing discontent over the war, Nixon announced on October 12, 1970 that the United States would withdraw 40,000 more troops before Christmas. Later that month on October 30, the worst monsoon to hit Vietnam in six years caused large floods, killed 293, left 200,000 homeless and virtually halted the war.

Backed by American air and artillery support, South Vietnamese troops invaded Laos on 13 February 1971. On August 18 of that year, Australia and New Zealand decided to withdraw their troops from Vietnam. The total number of American troops in Vietnam dropped to 196,700 on 29 October 1971, the lowest level since January 1966. On November 12, 1971 Nixon set a 1 February 1972 deadline to remove another 45,000 American troops from Vietnam.

On April 22, 1971, John Kerry became the first Vietnam veteran to testify before Congress about the war, when he appeared before a Senate committee hearing on proposals relating to ending the war. He spoke for nearly two hours with the Senate Foreign Relations Committee in what has been named the Fulbright Hearing, after the Chairman of the proceedings, Senator J. William Fulbright. Kerry presented the conclusions of the Winter Soldier Investigation, where veterans had described personally committing or witnessing war crimes.

In the 1972 election, the war was once again a major issue in the United States. An antiwar candidate, George McGovern, ran against President Nixon. Nixon's Secretary of State, Henry Kissinger, declared that "Peace is at Hand" shortly before the voters went to the polls, dealing a death blow to McGovern's campaign, which had been facing an uphill battle. However, the peace agreement was not signed until the next year, leading many to conclude that Kissinger's announcement was just a political ploy. Kissinger's defenders assert that the North Vietnamese negotiators had made use of Kissinger's pronouncement as an opportunity to embarrass the Nixon Administration to weaken it at the negotiation table. White House Press Secretary Ron Ziegler on 30 November 1972 told the press that there would be no more public announcements concerning American troop withdrawals from Vietnam due to the fact that troop levels were then down to 27,000. The US halted heavy bombing of North Vietnam on December 30, 1972.

A campaign to bomb Vietnam's dikes and thus threaten the North Vietnamese food supply was employed to pressure the North to concede, the details of which only began to surface much later.

The end of the war

Vietnamescape.jpg

On 15 January 1973, citing progress in peace negotiations, President Nixon announced the suspension of offensive action in North Vietnam which was later followed by a unilateral withdrawal of US troops from Vietnam. The Paris Peace Accords were later signed on 27 January 1973 which officially ended US involvement in the Vietnam conflict. This won the 1973 Nobel Peace Prize for Kissinger and North Vietnam's Prime Minister Le Duc Tho while fighting continued, leading songwriter Tom Lehrer to declare that irony had died. However, five days before the peace accords were signed, Lyndon Johnson, whose presidency was marred by the war, died. The mood during his state funeral was one of intense sadness and recrimination because the war's wounds were still raw.

The first American prisoners of war were released on February 11 and all US soldiers were ordered to leave by March 29. In a break with history, soldiers returning from the Vietnam War were generally not treated as heroes, and soldiers were sometimes even condemned for their participation in the war.

The peace agreement did not last.

Nixon had promised South Vietnam that he would provide military support to them in the event of a crumbling military situation. Nixon was fighting for his political life in the growing Watergate Scandal at the time. Economic aid continued, but most of it was siphoned off by corrupt elements in the South Vietnamese government and little of it actually went to the war effort. At the same time aid to North Vietnam from the USSR and China began to increase, and with the Americans out, the two countries no longer saw the war as significant to their US relations. The balance of power had clearly shifted to the North.

In December 1974, Congress completed passage of the Foreign Assistance Act of 1974 that voted to cut off all military funding to the Saigon government and made unenforceable the peace terms negotiated by Nixon.

By 1975, the South Vietnamese Army stood alone against the powerful North Vietnamese. Despite Vietnamization and the 1972 victories against the NVA offensive, the ARVN was plagued with corruption, desertion, low wages, and lack of supplies. Then in early March the NVA launched a powerful offensive into the poorly defended Central Highlands, splitting the Republic of South Vietnam in two. President Thieu, fearful that ARVN troops in the northern provinces would be isolated due to a NVA encirclement, he decided on a redeployment of ARVN troops from the northern provinces to the Central Highlands. But the withdrawal of South Vietnamese forces soon turned into a bloody retreat as the NVA crossed the DMZ. While South Vietnamese forces retreated from the northern provinces, splintered South Vietnamese forces in the Central Highlands fought desperately against the NVA.

On March 11, 1975 Bumnethout fell to the NVA. The attack began in the early morning hours. After a violent artillery barrage, 4,000- man garrison defending the city retreated with their families. On March 15, President Thieu ordered the Central Highlands and the northern provinces to be abandoned, in what he declared to lighten the top and keep the bottom. General Phu abandoned the cities of Pleiku and Kontum and retreated to the coast in what became known as the column of tears. General Phu led his troops to Tum Ky on the coast, but as the ARVN retreated, the civilians also went with them. Due to already destroyed roads and bridges, the column slowed down as the NVA closed in. As the column staggered down mountains to the coast, NVA shelling attacked. By April 1, the column ceased to exist after 60,000 ARVN troops were killed.

On March 20, Thieu reversed himself and ordered Hue, Vietnam’s 3rd largest city be held out at all cost. But as the NVA attacked, a panic ensued and South Vietnamese resistance collapsed. On March 22, the NVA launched a siege on Hue, the civilians, remembering the 1968 massacre jammed into the airport, seaports, and the docks. Some even swam into the ocean to reach boats and barges. The ARVN routed with the civilians and some South Vietnamese shot civilians just to make room for themselves. On March 25, after a 3-day siege, Hue fell.

As Hue fell, NVA rockets hit downtown Da Nang and the airport. By March 28, 35,000 NVA troops were poised in the suburbs. On March 29, a World Airways jet led by Edward Daley landed in Da Nang to save women and children, instead 300 men jammed onto the flight, mostly ARVN troops. On March 30, 100,000 leaderless ARVN troops surrendered as the NVA marched victoriously through Da Nang on that Easter Sunday. With the fall of Da Nang, the defense of the Central Highlands and northern provinces collapsed. With half of South Vietnam under their control, NVA prepared for its final phase in its offensive, the Ho Chi Minh campaign, the plan: By May 1, capture Saigon before South Vietnamese forces could regroup to defend it.

The NVA continued its attack as South Vietnamese forces and Thieu regime crumbled before their onslaught. On April 7, 3 NVA divisions attacked Xuan-loc, 40 miles east of Saigon , where they met fierce resistance from the ARVN 18th Infantry division. For 2 bloody weeks. Severe fighting raged in the city as the ARVN defenders in a last-ditch effort tried desperately to save South Vietnam from military and economic collapse. Also , hoping Americans forces would return in time to save them. The ARVN 18th Infantry division used many advanced weapons against the NVA , and it was in the final phase in which Saigon government troops fought well. But on April 21, the exhausted and besieged army garrison defending Xuan-loc surrendered. A bitter and tearful Thieu resigned on April 21, saying America had betrayed South Vietnam and he showed the 1972 document claiming America would retaliate against North Vietnam should they attack. Thieu left for Taiwan on April 25, leaving control of the doomed government to General Minh.

By now NVA tanks had reached Bienhoa, they turned towards Saigon, clashing with few South Vietnamese units on the way. The end was near.

Fall of Saigon

Main article: Fall of Saigon