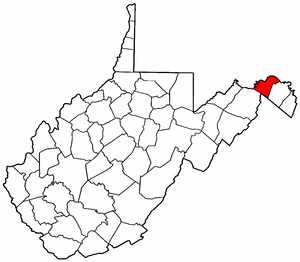

Morgan County, West Virginia

|

|

Morgan County is a county located in the state of West Virginia. As of 2000, the population is 14,943. Its county seat is Berkeley Springs6.

| Contents |

Geography

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the county has a total area of 595 km² (230 mi²). 593 km² (229 mi²) of it is land and 2 km² (1 mi²) of it is water. The total area is 0.30% water.

Magisterial Districts

Morgan.gif

Image:Morgan.gif

Demographics

As of the census2 of 2000, there are 14,943 people, 6,145 households, and 4,344 families residing in the county. The population density is 25/km² (65/mi²). There are 8,076 housing units at an average density of 14/km² (35/mi²). The racial makeup of the county is 98.30% White, 0.60% Black or African American, 0.17% Native American, 0.12% Asian, 0.01% Pacific Islander, 0.23% from other races, and 0.57% from two or more races. 0.83% of the population are Hispanic or Latino of any race.

There are 6,145 households out of which 28.70% have children under the age of 18 living with them, 57.90% are married couples living together, 8.20% have a female householder with no husband present, and 29.30% are non-families. 24.50% of all households are made up of individuals and 10.20% have someone living alone who is 65 years of age or older. The average household size is 2.40 and the average family size is 2.84.

The age distribution is 22.40% under the age of 18, 6.80% from 18 to 24, 27.30% from 25 to 44, 26.90% from 45 to 64, and 16.60% who are 65 years of age or older. The median age is 41 years. For every 100 females there are 96.60 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there are 95.00 males.

The median income for a household in the county is $35,016, and the median income for a family is $40,690. Males have a median income of $29,816 versus $22,307 for females. The per capita income for the county is $18,109. 10.40% of the population and 8.00% of families are below the poverty line. Out of the total population, 11.60% of those under the age of 18 and 8.80% of those 65 and older are living below the poverty line.

History

Morgan County was created by an act of the Virginia General Assembly in March 1820 from parts of Berkeley and Hampshire counties. It was named in honor of General Daniel Morgan (1736-1802). He was born in Hunterdon County, New Jersey, and moved to Winchester, Virginia as a youth. He served as a wagoner in Braddock's Army during the campaign against the Indians in 1755. During the campaign, a British Lieutenant became angry with him and hit him with the flat of his sword. Morgan punched the Lieutenant, knocking him unconscious. Morgan was court-martialed for striking a British officer and was sentenced to 500 lashes. Morgan later joked that the drummer who counted out the lashes miscounted and he received only 499 lashes. For the rest of his life he claimed the British still owed him one.

After the campaign ended, he bought a two-story house in Winchester, Virginia where he and Abigail Curry established a home. They had two daughters and were later married in 1773. When the American Revolutionary War broke out, he joined the American army and, in July 1775, was commissioned a Captain of the Virginia riflemen. He was captured during the Battle of Quebec in December 1775 and spent the next eight months as a prisoner of war. He was paroled under the promise of a prisoner exchange and later distinguished himself at the Battles of Saratoga in 1777. In 1779, he resigned from the army after he was passed over for promotion to Brigadier General. In 1780, he accepted command of the Southern Campaign and, soon afterwards, was promoted to Brigadier General. In 1790, the Continental Congress awarded him a gold star for his victory at the Battle of Cowpens, South Carolina on January 17, 1781.

After the war, he returned to Winchester. During his retirement he was a frequent visitor to Bath (Berkeley Springs) in hopes that the warm waters would provide some relief for his gout. He was called out of retirement in 1794 and put in command of the Virginia military during the Whiskey Rebellion that was suppressed that year. In 1797, he was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives and served there for two years before retiring due to ill health. He died in Winchester on July 6, 1802.

The First Settlers

The Mound Builders, also known as the Adena people, were the first known settlers in present-day West Virginia's Eastern Panhandle region (Berkeley, Jefferson, and Morgan counties). Remnants of the Mound Builder's civilization have been found throughout West Virginia, with a high concentration of artifacts in Moundsville, West Virginia (Marshall County). The Grave Creek Indian Mound, located in Moundsville, is one of West Virginia's most famous historic landmarks. More than 2,000 years old, it stands 69 feet high and 295 feet in diameter.

According to missionary reports, several thousand Hurons occupied present-day West Virginia, including the Eastern Panhandle region, during the late 1500s and early 1600s. During the 1600s the Iroquois Confederacy (then consisting of the Mohawk, Onondaga, Cayuga, Oneida, and Seneca tribes) drove the Hurons from the state. The Iroquois Confederacy was headquartered in New York and was not interested in occupying present-day West Virginia. Instead, they used it as a hunting ground during the spring and summer months.

During the early 1700s, West Virginia's Eastern Panhandle region was inhabited by the Tuscarora. They eventually migrated northward into New York and, in 1712, became the sixth nation to be formally admitted into the Iroquois Confederacy. The Eastern Panhandle region was also used as a hunting ground by several other Indian tribes, including the Shawnee (also known as the Shawanese) who resided near present-day Winchester, Virginia and Moorefield, West Virginia until 1754 when they migrated into Ohio. The Mingo, who resided in the Tygart Valley and along the Ohio River in present-day West Virginia's Northern Panhandle region, and the Delaware, who lived in present-day eastern Pennsylvania, New Jersey and Delaware, but had several autonomous settlements as far south as present-day Braxton County, also used the area as a hunting ground.

The Mingo were not actually an Indian tribe, but a multi-cultural group of Indians that established several communities within present-day West Virginia. They lacked a central government and, like all other Indians within the region at that time, were subject to the control of the Iroquois Confederacy. The Mingo originally lived closer to the Atlantic Coast, but European settlement pushed them into western Virginia and eastern Ohio.

The Seneca, headquartered in western New York, was the closest member of the Iroquois Confederacy to West Virginia, and took great interest in the state. In 1744, the Seneca boasted to Virginia officials that they had conquered the several nations living on the back of the great mountains of Virginia. Among the conquered nations were the last of the Canawese or Conoy people who became incorporated into the Iroquois communities in New York. The Conoy continue to be remembered today through the naming of two of West Virginia's largest rivers after them, the Little Kanawha and the Great Kanawha.

Seneca war parties, and war parties from other members of the Iroquois Confederacy, often traveled through the state to protect its claim to southern West Virginia from the Cherokee. The Cherokee were headquartered in western North Carolina and eastern Tennessee and rivaled the Iroquois nation in both size and influence. The Cherokee claimed present-day southern West Virginia as their own, setting the stage for conflict with the Iroquois Confederacy. In 1744, Virginia officials purchased the Iroquois title of ownership to West Virginia in the Treaty of Lancaster. The treaty reduced the Iroquois Confederacy's presence in the state.

During the mid-1700s, the English indicated to the various Indian tribes residing in present-day West Virginia that they intended to settle the frontier. The French, on the other hand, were more interested in trading with the Indians than settling in the area. This influenced the Mingo to side with the French during the French and Indian War (1755-1763). Although the Iroquois Confederacy officially remained neutral, many in the Iroquois Confederacy also allied with the French. Unfortunately for them, the French lost the war and ceded their North American possessions to the British.

Following the war, the Mingo retreated to their homes along the banks of the Ohio River and were rarely seen in the eastern panhandle region. Although the French and Indian War was officially over, many Indians continued to view the British as a threat to their sovereignty and continued to fight them. In the summer of 1763, Pontiac, an Ottawa chief, led raids on key British forts in the Great Lakes region. Shawnee chief Keigh-tugh-qua, also known as Cornstalk, led similar attacks on western Virginia settlements, starting with attacks in present-day Greenbrier County and extending northward to Bath, now known as Berkeley Springs, and into the northern Shenandoah Valley. By the end of July, Indians had destroyed or captured all British forts west of the Alleghenies except Fort Detroit, Fort Pitt, and Fort Niagara. The uprisings were ended on August 6, 1763 when British forces, under the command of Colonel Henry Bouquet, defeated Delaware and Shawnee forces at Bushy Run in western Pennsylvania.

Although hostilities had ended, England's King George III feared that more tension between Native Americans and settlers was inevitable. In an attempt to avert further bloodshed, he issued the Proclamation of 1763, prohibiting settlement west of the Allegheny Mountains. The next five years were relatively peaceful on the frontier. However, many land speculators violated the proclamation by claiming vast acreage in western Virginia. In 1768, the Iroquois Confederacy (often called the Six Nations) and the Cherokee signed the Treaty of Hard Labour and the Treaty of Fort Stanwix, relinquishing their claims on the territory between the Ohio River and the Alleghenies to the British. With the frontier now open, settlers, once again, began to enter into present-day West Virginia.

During the spring of 1774 there were several incidents between the Shawnee and surveying parties traveling within present-day West Virginia which resulted in the deaths of several surveyors and Indians. Captain Michael Cresap led efforts to put down the Indian uprising, leading to what some called "Cresap's War." The most serious encounter took place in April 1774. Although there are conflicting accounts over what occurred, most accounts indicate that several Indians stole some property from white settlers near present-day Wheeling. In retaliation, several settlers from the area, led by Daniel Greathouse, an associate of Cresap's, followed their trail and came upon two Indians on the north side of the Ohio River. Believing them to be the thieves, the settlers killed them. The next day, April 30, 1774, the settlers found four Indians at a local tavern owned by Joshua Baker. The tavern was located on the southern side of the Ohio River across from the mouth of Yellow Creek which enters the Ohio River several miles above present-day Wheeling. After getting the Indians drunk, the settlers killed them as well. Four more Indians approached the tavern inquiring about the whereabouts of the missing Indians, among them was the brother and pregnant sister of Logan, the now-famous Mingo Indian Chief. The settlers killed them as well, and, reportedly, mutilated Logan's sister's body. After learning of his brother and sister's deaths, Logan led a series of attacks on settlements along the upper Monongahela River and in the neighborhood of Redstone Creek, where the settlers who committed the killings originated. Logan later admitted to killing at least thirteen settlers that summer. He was convinced that Michael Cresap was responsible for his brother's murder and the killing and mutilation of his sister, but it was later determined that Cresap was not responsible.

Following what the Indians referred to as the Yellow Creek Massacre, violence between settlers and the various Indian tribes spread across western Virginia. Virginia Governor John Murray, 4th Earl of Dunmore, decided to end the Indian uprising by force. He formed two armies. He led the first army, which was comprised of 1,700 men drawn primarily from the upper Shenandoah Valley, including present-day West Virginia's Eastern Panhandle region. Colonel Andrew Lewis led the second army. It was comprised of 800 men, drawn primarily from the lower Shenandoah Valley. The two armies marched into western Virginia to meet the Indians, which was led by Shawnee chieftain Keigh-tugh-qua, also known as Cornstalk. Lord Dunmore's army took a more northerly route through present-day West Virginia and Colonel Lewis' army took a more southerly route. Aware of their presence, the Indians, comprised of approximately 1,200 Shawnee, Delaware, Mingo, Wyandotte and Cayuga warriors, decided to attack Lewis' army on October 10, 1774. They hoped to defeat Colonel Lewis' army before it united with Lord Dunmore's army. The attack took place at the confluence of the Kanawha and Ohio Rivers, at present-day Point Pleasant, in Mason County. During the battle, both sides suffered significant losses.

Although nearly half of Lewis' commissioned officers were killed during the battle, including his brother, Colonel Charles Lewis, and seventy-five of his non-commissioned officers, the Indians were forced to retreat back to their settlements in Ohio's Scioto Valley, with Lewis' men in pursuit. Meanwhile, Lord Dunmore arrived and joined forces with Lewis. Seeing that they were outnumbered, Cornstalk sued for peace.

Although western Virginia's settlers continued to experience isolated Indian attacks for several years, Cornstalk's defeat at Point Pleasant was the beginning of the end of the Indian presence in western Virginia. The Indians agreed to give up all of their white prisoners, restore all captured horses and other property, and not to hunt south of the Ohio River. They also agreed to stop harassing boats on the Ohio River. This opened up present-day West Virginia and Kentucky for settlement. Cornstalk was later killed at Fort Randolph near Point Pleasant in 1777 in retaliation for the death of a militiaman who was killed by an Indian.

During the American Revolutionary War (1776-1783), the Mingo and Shawnee, headquartered at Chillicothe, Ohio, allied themselves with the British. In 1777, a party of 350 Wyandots, Shawnees and Mingos, armed by the British, attacked Fort Henry, near present-day Wheeling. Nearly half of the soldiers manning the fort were killed in the three-day assault. The Indians then left the area celebrating their victory. For the remainder of the war, smaller raiding parties of Mingo, Shawnee, and other Indian tribes terrorized settlers throughout northern and eastern West Virginia. As a result, European settlement throughout present-day West Virginia, including the Eastern Panhandle, came to a virtual standstill until the war's conclusion. Following the war, the Mingo and Shawnee, once again allied with the losing side, returned to their homes. As the number of settlers in present-day West Virginia began to grow, both the Mingo and Shawnee moved further inland, leaving their traditional hunting ground to the white settlers.

Morgan County's European Settlers

The first English settlers in present-day Morgan County arrived during the 1730s. Because most of these early pioneers were squatters, there is no record of their names. Historians claim that the first cabin in the county was built around 1745. As word of the county's warm springs spread eastward, Thomas Fairfax, 6th Lord Fairfax of Cameron decided that the county needed to be surveyed. In 1748, George Washington, then just sixteen years old, was part of the survey party the surveyed the Eastern Panhandle region for Lord Fairfax. He later returned to Bath (Berkeley Springs) several times over the next several years with his half-brother, Laurence, who was ill and hoped that the warm springs might improve his health. The springs, and their rumored medicinal benefits, attracted numerous Indians as well as Europeans to the area.

In April 1754, Colonel Joshua Fry and his second-in-command, Lieutenant Colonel George Washington, led a force of nearly 400 Virginians, many of them from the Eastern Panhandle region, toward Fort Duquesne in an attempt to drive the French from the area. Washington and about forty of his men reached Great Meadows, in present-day Farmington, Pennsylvania, in late May 1754 and surprised an encampment of thirty-four French soldiers. Ten of the French soldiers were killed, one was wounded, twenty-one were taken prisoner, and one escaped and headed for the main French garrison at Fort Duquesne. Anticipating a counter-attack, Washington ordered the construction of a circular palisaded fort which he named Fort Necessity. Meanwhile, Colonel Fry was killed in a separate engagement, leaving Washington in command. Over the next several weeks, the rest of the Virginia command made its way to Fort Necessity. On July 3, 1754, approximately 600 French soldiers, accompanied by about 100 Indians, attacked the Fort. After exchanging gun fire throughout the day, Washington, realizing that he was outnumbered and surrounded, agreed to surrender Fort Necessity. The following day he marched out of the Fort and led his men back toward Virginia. The French then burned Fort Necessity and returned to Fort Duquesne. Many historians consider the Battle of Fort Necessity to be the opening battle of the French and Indian War (1754-1763).

Important Events in Morgan County during the 1700s

As mentioned previously, George Washington visited present-day Berkeley Springs several times with his half-brother, Laurence. When he vacationed in the area in 1767, he noted how busy the town had become. Lord Fairfax had built a summer home there and a "private bath" making the area a popular destination for Virginia's social elite. As the town continued to grow, the Virginia General Assembly decided to formally recognize it. In October 1776, the town was officially named Bath, in honor of England's spa city called Bath. The town's main north-south street was named Washington and the main east-west street was named Fairfax. Also, seven acres were set aside for "suffering humanity." When West Virginia gained statehood, those acres became West Virginia's first state park.

Bath's population increased during and immediately after the American Revolutionary War as wounded soldiers and others came to the area believing that the warm springs had medicinal qualities. Bath gained a reputation as a somewhat wild town where eating, drinking, dancing and gambling on the daily horse races were the order of the day.

Bath later became known as Berkeley Springs, primarily because the town's post office took that name (combining Governor Norborne Berkeley's last name with the warm springs found there) to avoid confusion with another post office, located in southeastern Virginia, which was already called Bath. Because the mail was sent to and from Berkeley Springs, that name slowly took precedence.

The Morgan County Seat

The Morgan County court met for the first time in Bath on March 16, 1820 in Ignatious O'Ferrall's tavern. Later meetings were held at the Buck Horn Tavern until a building was purchased for the court's use. Initially, Morgan County's government was dominated by Molly Abernathy and her two lawyer sons, John and Joseph. The main order of business at that time was keeping the peace in town, and the construction of roads to and from the county seat.

Cities and towns

- Berkeley Springs

- The town is incorporated as Bath, but is generally called by the name of its post office, Berkeley Springs.

- Paw Paw

References

- Fowler, Virginia G. 2002. Brigadier General Daniel Morgan, Washington, D.C.: National Park Service. Available on-line at: [[1] (http://www.nps.gov/cowp/dmorgan.htm)]

- Morgan County Historical and Genealogical Society. 1981. Morgan County, West Virginia and Its People. Berkeley Springs: Morgan County Historical and Genealogical Society.

- Cartmell, Thomas Kemp. 1909. Shenandoah Valley Pioneers and Their Descendants: A History of Frederick County, Virginia. Winchester, VA: The Eddy Corporation.

- Newbraugh, Frederick T. 1967. Warm Springs Echoes: About Berkeley Springs and Morgan County. Part 1: To 1860. Hagerstown, MD: Automated Systems Corporation.

- Dr. Robert Jay Dilger, Director, Institute for Public Affairs and Professor of Political Science, West Virginia University.

|

State of West Virginia |

|---|---|

| State Capital: | |

| Regions: |

Baltimore-Washington Metropolitan Area | Eastern Panhandle | Northern Panhandle | Allegheny Plateau | Cumberland Plateau | Ridge-and-valley Appalachians |

| Major Cities: | |

| Smaller Cities: |

Beckley | Bluefield | Clarksburg | Fairmont | Hurricane | Keyser | Morgantown | Oak Hill | Parkersburg | Point Pleasant | Weirton | Wheeling |

| Counties: |

Barbour | Berkeley | Boone | Braxton | Brooke | Cabell | Calhoun | Clay | Doddridge | Fayette | Gilmer | Grant | Greenbrier | Hampshire | Hancock | Hardy | Harrison | Jackson | Jefferson | Kanawha | Lewis | Lincoln | Logan | Marion | Marshall | Mason | McDowell | Mercer | Mineral | Mingo | Monongalia | Monroe | Morgan | Nicholas | Ohio | Pendleton | Pleasants | Pocahontas | Preston | Putnam | Raleigh | Randolph | Ritchie | Roane | Summers | Taylor | Tucker | Tyler | Upshur | Wayne | Webster | Wetzel | Wirt | Wood | Wyoming |