History of the European Union

|

|

Template:Life in the European Union This is the history of the European Union. See also the history of Europe and history of present-day nations and states.

| Contents |

Pre-1945 influences

Attempts to unify the disparate nations of Europe precede the modern nation-states and have occurred repeatedly throughout the history of Continental Europe since the collapse of the Mediterranean-centred Roman Empire. Europe's heterogeneous collection of languages and cultures made attempts based on dynastic rights, or enforced through military occupation of unwilling nations, unstable and doomed to failure.

The Frankish empire of Charlemagne and the Holy Roman Empire united large areas under a loose administration for hundreds of years.

Once Arabs had conquered ancient centres of Christianity in Syria and Egypt during the 8th century, the concept of "Christendom" became essentially a concept of a unified Europe, but always more of an ideal than an actuality. The Great Schism between Orthodoxy and Catholicism rendered the idea of "Christendom" moot. After the Fall of Constantinople to the Turks in 1453, the first proposal for peaceful methods of unifying Europe against a common enemy emerged. George of Podebrady, a Hussite king of Bohemia proposed the creation of a union of Christian nations against the Turks in 1464.

In 1569, the Union of Lublin transformed the Polish-Lithuanian personal union into the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, a multi-national federation and elective monarchy, which lasted until the partitions of Poland in 1795.

In 1728, Abbot Charles de Saint-Pierre proposed the creation of a European league of 18 sovereign states, with common treasury, no borders and an economic union.

After the American Revolution of 1776 the vision of a United States of Europe similar to the United States of America was shared by some prominent Europeans, notably the Marquis de Lafayette and Tadeusz Kosciuszko.

Some suggestion of a European union can be found in Immanuel Kant's 1795 proposal for an "eternal peace congress."

In the 1800s, customs union under Napoleon Bonaparte's Continental system was promulgated in November 1806 as an embargo of British goods in the interests of French hegemony. It demonstrated the workability and also the flaws of a supranational economic system for Europe.

In the conservative reaction after Napoleon's defeat in 1815, the German Confederation (German "Deutscher Bund") was established as a loose association of thirty-eight German states formed by the Congress of Vienna. Napoleon had swept away the Holy Roman Empire and simplified the map of Germany. The German Confederation was an association of independent, equal sovereign nation states. In 1834, the Zollverein (German, "customs union") was formed among the states of the Confederation, in order to create better trade flow and reduce internal competition.

Italian writer and politician Giuseppe Mazzini called for the creation of a federation of European republics in 1843. This set the stage for perhaps, the best known early proposal for peaceful unification, through cooperation and equality of membership, made by the pacifist Victor Hugo in 1847. Hugo spoke in favour of the idea at a peace congress organised by Mazzini, but was laughed out of the hall. However, he returned to his idea again in 1851.

Following the catastrophe of the First World War, some thinkers and visionaries again began to float the idea of a politically unified Europe. In 1923, the Austrian Count Coudenhove-Kalergi founded the Pan-Europa movement and hosted the First Paneuropean Congress, held in Vienna in 1926.

In 1929, Aristide Briand, French prime minister, gave a speech in the presence of the League of Nations Assembly in which he proposed the idea of a federation of European nations based on solidarity and in the pursuit of economic prosperity and political and social co-operation. Many eminent economists, among them John Maynard Keynes, supported this view. At the League's request Briand presented a Memorandum on the organisation of a system of European Federal Union in 1930.

In 1931 the French politician Edouard Herriot published the book The United States of Europe.

The Great Depression, the rise of fascism and subsequently World War II prevented this inter war movement gaining further support.

In 1940, following Germany's military successes in World War II and Nazi planning for the creation of a thousand year Reich, a European confederation was proposed by German economists and industrialists. They argued for a "European economic community", with a customs union and fixed internal exchange rates. In 1943, the German ministers Joachim von Ribbentrop and Cecil von Renthe-Fink eventually proposed the creation of a European confederacy, which would have had a single currency, a central bank in Berlin, a regional principle, a labour policy and economic and trading agreements. The proposed countries to be included were Germany, Italy, France, Denmark, Norway, Finland, Slovakia, Hungary, Bulgaria, Romania, Croatia, Serbia, Greece and Spain. Such a German-led Europe, it was hoped, would serve as a strong alternative to the Communist Soviet Union and also be a counterweight to British dominance of world trade. The later Foreign Minister Arthur Seyss-Inquart said: "The new Europe of solidarity and co-operation among all its people will find rapidly increasing prosperity once national economic boundaries are removed", while the Vichy French Minister Jacques Benoist-Mechin said that France had to "abandon nationalism and take place in the European community with honour."

These pan-European illusions from the early 1940s were never realised, not least because neither Hitler, nor many of his leading hierarchs such as Goebbels, had the slightest intention to compromise absolute German hegemony through the creation of a European confederation. An integrated Europe based on Nazi conquest and lacking a democratic structure could not have been a true predecessor of the European Union.

In 1943, Jean Monnet a member of the National Liberation Committee of the Free French government in exile in Algiers, and regarded by many as the future architect of European unity, is recorded as declaring to the committee:- "There will be no peace in Europe, if the states are reconstituted on the basis of national sovereignty... The countries of Europe are too small to guarantee their peoples the necessary prosperity and social development. The European states must constitute themselves into a federation..."

Post 1945 impetus

By the end of the war, a new impetus for the founding of (what was later to become) the European Union was the desire to rebuild Europe after the disastrous events of World War II, and to prevent Europe from ever again falling victim to the scourge of war. In order to do this, many supported the idea of forming some form of European federation or government. Winston Churchill gave a speech (http://www.peshawar.ch/varia/winston.htm) at the University of Zürich on September 19, 1946 calling for a "United States of Europe", similar to the United States of America. The immediate result of this speech was the forming of the Council of Europe in 1949. The Council of Europe however was (and still remains) a rather restricted organisation, like a regional equivalent of the United Nations (though it has developed some powers in the area of human rights, through the European Court of Human Rights.)

The three communities

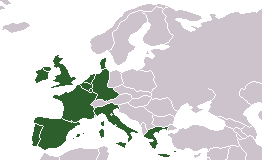

Crude-EU6.png

The European Union grew out of the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC), which was founded in 1951, by the six founding members: Belgium, the Netherlands and Luxembourg (the Benelux countries) and (West) Germany, France and Italy. Its purpose was to pool the steel and coal resources of the member states, thus preventing another European war. It was in fulfilment of a plan developed by a French civil servant Jean Monnet, publicised by the French foreign minister Robert Schuman. On May 9, 1950 Schuman presented his proposal on the creation of an organised Europe stating that it was indispensable to the maintenance of peaceful relations. This proposal, known as the "Schuman declaration", is considered to be the beginning of the creation of what is now the European Union, which later chose to celebrate May 9 as Europe Day. The British were invited to participate in it, but refused on grounds of national sovereignty; thus the six went ahead alone. (See Text of the Schuman declaration (http://europa.eu.int/abc/symbols/9-may/decl_en.htm)).

Rometreaty.jpg

The ECSC was followed by attempts, by the same member-states, to found a European Defence Community (EDC) and a European Political Community (EPC). The purpose of this was to establish a common European army, under joint control, so that West Germany could be safely permitted to rearm and help counter the Soviet threat. The EPC was to establish a federation of European states. However, the French National Assembly refused to ratify the EDC treaty, which led to its abandonment. After the failure of the EDC treaty, the EPC was quietly shelved. The idea of both institutions can be seen to live on, in a watered down form, in later developments, such as European Political Co-operation (also called EPC), the Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP) pillar established by the Maastricht treaty, and the European Rapid Reaction Force currently in formation.

Following the failure of the EDC and EPC, the six founding members tried again at furthering their integration, and founded the European Economic Community (EEC), and the European Atomic Energy Community (Euratom). The purpose of the EEC was to establish a customs union among the six founding members, based on the "four freedoms": freedom of movement of goods, services, capital and people. Euratom was to pool the non-military nuclear resources of the states. The EEC was by far the most important of the three communities, so much so that it was later renamed simply the European Community. It was established by the Treaty of Rome of 1957 and implemented January 1 1958.

The growth of these European Communities into what is currently the European Union can be said to consist of two parallel processes -- first their structural evolution and institutional change into a tighter bloc with more competences given to the supranational level, which can be called the process of European integration or the deepening of the Union. The other is the enlargement of the European Communities (and later European Union) from 6 to 25 member states, which is also called the widening of the Union. We will examine these in turn.

Enlargement of the EU

1973

Crude-EU9.png

In January 1960, Britain and other OEEC members who didn't belong to the EEC formed an alternative association, the European Free Trade Association. But Britain soon realised that the EEC was more successful than the EFTA and decided to apply for membership. Ireland and Denmark, both of whom being heavily reliant on British trade, decided they would go wherever Britain went, and hence also applied to join the Community. Norway also applied at this time.

The first application occurred under the Conservative government of Harold Macmillan, who was more favourable to Britain joining the EEC than his predecessors. Negotiations started in November 1961 and a provisional agreement was reached in July 1962. However, Britain's membership was vetoed by French president Charles De Gaulle in January 1963 (all EEC founding members had this right). Officially, De Gaulle said that Britain was not sufficiently European-minded yet to break away from the Commonwealth and accept a common agricultural policy. But other reasons include Britain's close relationship with the US in terms of defence (see Nassau agreement) and De Gaulle's fear that Britain's membership would be followed by many other countries joining the EEC, thus making the community lose its cohesion. De Gaulle refused an "Atlantic" Europe. As a result, the whole negotiations with the four countries broke off.

The second application occurred under the Labour government of Harold Wilson. Wilson said in April 1966 that Britain was ready to apply for EEC membership if essential British interests were safeguarded. Negotiations started on May 1967 with the four countries but De Gaulle used once again his right of veto in September 1967. Officially, De Gaulle said that Britain had to improve its economy but he actually still feared that Britain would act as the US trojan horse. The whole negotiation broke off once again, and it seemed that Britain wouldn't be able to join the EEC as long as De Gaulle would be president.

The third and last application occurred after De Gaulle resigned in 1969 and was replaced by Georges Pompidou. In October 1969, the European Commission asked for new negotiations concerning the applications of the four countries. In November 1969, during a meeting of the foreign ministers of the EC (EEC, ECSC and Euratom had merged into the EC in 1967), French minister Maurice Schumann declared that France would agree to Britain's membership if questions of agricultural finance were settled first. Negotiations started in June 1970 under the Conservative government of Edward Heath, who was one of the most strongly pro-European politicians in Britain. Britain agreed to the conditions of the EC: Britain had to accept the Merger Treaty and all decisions taken since the second application, and resolve its problem of adaptation, i.e. conflicts between the EC and the Commonwealth. Finally, Britain joined successfully on January 1, 1973. In 1972, Ireland, Denmark, Norway held referenda on whether to join. The results were:

- Ireland - 83.1% in favour (May 10) (see also: Third Amendment of the Constitution of Ireland)

- Norway - 46.5% in favour (September 25)

- Denmark - 63.3% in favour (October 2)

Following the rejection by the Norwegian electorate (53.5% against), Norway did not join, an event that was to be repeated again twenty years later, when the government proposed joining along with Austria, Sweden and Finland.

1980s

Greece joined on January 1, 1981, under the presidency of Constantine Caramanlis.

In 1985, Denmark's territory Greenland left the union following home rule and a referendum. See Special member state territories and their relations with the EU for details.

In 1986, Spain and Portugal joined. This was one of the first times the member states began to consider the problems of immigration from new and poorer applicant nations. The German, French and UK press all circulated stories predicting uncontrollable immigration from the new members, flooding the labour market, lowering wages, and causing racial problems.

Such a fear didn't materialise, but a similar concern for the possibility of uncontrolled immigration was to occur again preceding the 2004 enlargement.

1995

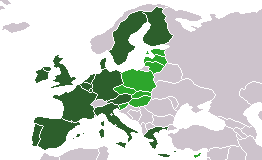

Crude-EU15.png

The 1994 referenda on membership were as follows:

- Austria - 66.6% in favour (June 12)

- Finland - 56.9% in favour (October 16)

- Sweden - 52.8% in favour (November 13)

- Norway - 43.1% in favour (November 28)

Austria, Sweden and Finland were admitted on January 1, 1995. As the referendum in Norway was 52.2% against joining, the proposal by the Norwegian government to join was rejected for the second time.

With the departure of Austria, Sweden and Finland to the EU, only Norway, Iceland, Switzerland and Liechtenstein remain members of the EFTA.

2004

The European Commission's Strategic Report of October 9, 2002 recommended 10 candidate members for inclusion in the EU in 2004: Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, the Czech Republic, Hungary, Slovakia, Slovenia, Malta and Cyprus. Their combined population is roughly 75 million; their combined Gross Domestic Product was about 840 billion US dollars (purchasing power parity; CIA World Factbook 2003), similar in size to that of Spain.

This could therefore be called one of the most ambitious enlargements of the European Union yet. On the side of the European Union it was partly motivated by a desire to reunite Europe after the end of the Cold War, and an effort to tie Eastern Europe firmly to the West in order to prevent it falling again into communism or dictatorship.

Cyprus was made a candidate for admission because Greece threatened to veto the enlargement unless Cyprus was also allowed to be a part of it. The prospect of membership for the island also led to a significant (but eventually failed) push for reunification through the Annan Plan for Cyprus.

After negotiations between the candidates and the member states, the final decision to invite these nations to join was announced on December 13, 2002 in Copenhagen, with the European Parliament voting in favour of this on April 9, 2003.

On April 16, 2003 the Treaty of Accession was signed by the 10 new members and the 15 old ones in Athens. [1] (http://europa.eu.int/comm/enlargement/negotiations/treaty_of_accession_2003/index.htm).

The final remaining step was the ratification of the treaty by the current member states and by each of the candidate nations. Ratification in the former was done by the parliaments of the member states alone, whereas in the latter the ratification was first subject to a referendum, except for Cyprus where the parliament was solely responsible. The 2003 referenda dates (in four of the countries, a two-day ballot is held), and the outcomes in each of the candidate countries, are as follows:

- Malta - 54% in favour (March 8)

- Slovenia - 90% in favour (March 23)

- Hungary - 83% in favour (April 12)

- Lithuania - 91% in favour (May 10-11)

- Slovakia - 92% in favour (May 16-17)

- Poland - 77% in favour (June 7-8)

- Czech Republic - 77% in favour (June 13-14)

- Estonia - 67% in favour (September 14)

- Latvia - 67% in favour (September 20)

In the event that one of the referenda did not return an affirmative result, provision had been made for the enlargement to carry on without that country. However, the referenda results were all in favour of joining, ratification proceeded without problems and the candidate countries became full members of the EU on May 1, 2004.

2007

Bulgaria and Romania completed negotiation talks on December 14, 2004 and are set to join the Union on January 1, 2007. The Treaty of Accession of Bulgaria and Romania was signed on April 25, 2005, in Luxembourg giving the legislative bodies of the 25 EU-member states a year and a half to ratify the treaties.

On May 11, 2005 the Bulgarian National Assembly ratified the Treaty of Accession with the European Union. Two votes were held by the 240 member Parliament.

- First reading: 230 - "in favour", 1 - "against" and 2 - "abstentions"

- Second reading: 231 - "in favour", 1 - "against" and 2 - "abstentions"

On May 17, 2005 a joint session of the Romanian Senate and Chamber of Deputies ratified the Treaty of Accession with the European Union. The vote was held by the 469 member upper and lower houses.

- Results: 434 - "in favour", 0 - "against" and 0 - "abstentions"

History of European integration

One of the first crises affecting the course of European integration occurred in 1965. A switch away from unanimous decision-making and to majority-voting in the Council was supposed to have been made on January 1, 1966. However the De Gaulle government of France was firmly opposed to this, seeking that all discussions on decisions affecting national interests should be discussed indefinitely, essentially requiring the retention of national veto on all issues of importance. This led to the "empty chair policy" in which France refused to take its seat in the Council for a six month period starting in July 1965. Finally the Luxembourg compromise of January 1966 resolved the crisis by acknowledging the disagreement and beginning a policy where each member-state could wield a veto on matters it deemed of "national importance". In effect this meant member-states could use a veto, but only sparingly. This was a political gentlemen's agreement and not a treaty modification.

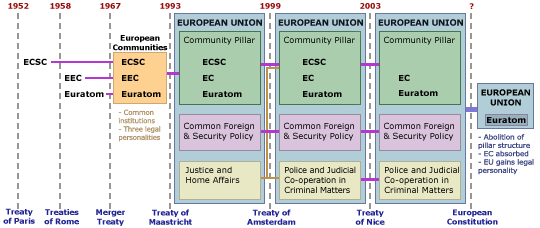

The three European Communities have always had identical memberships and similar institutional structures. Originally they shared the Court of Justice and Parliament in common, having separate Councils and Commissions (called the High Authority in the case of the ECSC); but the Merger Treaty of July 1967 merged their Councils and Commissions into a single Council and Commission. A customs union was established in 1968.

The first direct elections for the European Parliament were held in 1979, after a decision to that effect was first adopted in 1976 and ratified in 1978.

The first step in transforming the European Communities into the European Union was made with the Solemn Declaration on European Union (also known as the Stuttgart Declaration), of 19 June, 1983.

In 1986 the Single European Act was signed, the first step towards the single European market. At the same it formally introduced the concept of European Political Cooperation.

In 1992, the Maastricht treaty was signed, which at the same time modified the Treaty of Rome. It established the European Union, turning the European Communities into the EU's so-called "first-pillar", and adding two further pillars of cooperation, on Common Foreign and Security Policy and on Justice and Home Affairs. At the same time it established Economic and Monetary Union as a formal objective. The Maastricht treaty came into force in 1993.

The European Economic Area was founded in 1994 in order to allow EFTA countries to participate in the Single Market without having to join the EU.

In 1997, the Treaty of Amsterdam was signed, which updated the Maastricht treaty and aimed to make the EU more democratic.

In January 1999, eleven countries (Austria, the Benelux countries, Finland, France, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Portugal and Spain) agreed to join the Euro and abandon their existing currencies. Greece joined two years later, in January 2001, bringing the members of the eurozone to twelve. On January 1 2002, Euro notes and coins entered circulation.

Current issues

| This article or section contains information about a current or ongoing event. |

| Information may change rapidly as the event progresses and may temporarily contain inaccuracies, bias, or vandalism due to a high frequency of edits. |

Currently, the EU is undergoing organisational difficulties, especially those dealing with the proposed European Constitution. The new constitution must be ratified by all 25 member states before it can enter into force, in some cases by national referenda. To date, although ten countries have ratified the constitution, voters in France and the Netherlands have rejected it in popular votes. The future of the constitution is now uncertain.

Some also believe there is inconsistent application of EU laws in favour of larger member states: while smaller countries like Portugal have been 'called to the carpet' for failing to control deficits, both France and Germany appeared to have been given a free hand by the EU finance ministers (and against the wishes of the EU Commission) to ignore the Stability and Growth Pact. [2] (http://www.johnbeggs.com/jb/comment.asp?20022002119)

Others argue that the rules of the Stability and Growth Pact, which has been called "stupid" and "rigid" by former EU Commission President Romano Prodi, are deeply flawed, and therefore urgently need to be revised. [3] (http://www.nber.org/~wbuiter/banker.pdf)

Recently the EU Court of Justice ruled in this issue in favour of the EU Commission, deciding that the finance ministers' decision to annul the sanctions was unlawful.

Another issue is the application for EU membership of Turkey. On 16-17 December 2004, at the Council summit of the 25 EU leaders in Brussels, Turkey finally won its reward for "decisive progress" in reforming its economy and improving its domestic human rights situation: a target date of 3 December 2005 for opening accession negotiations. [4] (http://europa.eu.int/comm/enlargement/docs/newsletter/latest_weekly.htm#D). Nonetheless, there is still significant concern about Turkey's suitability as a member, for political, cultural and economic reasons. There's also a question of its continuing disputes with Greece and Cyprus.

See also

- Enlargement of the European Union - more on current and future enlargement

- European Community

- European Union

- European Free Trade Association (EFTA) - the organisation established in 1960 as an alternative for European states that did not wish to join the European Community.

External link

- Chronology of the history of the EU (http://www.europa.eu.int/abc/history/index_en.htm)cy:Hanes yr Undeb Ewropeaidd

da:EU's historie de:Geschichte der Europäischen Union es:Historia de la Unión Europea fr:Histoire de l'Union européenne nl:Geschiedenis van de Europese Unie no:EUs historie pl:Historia Unii Europejskiej