Hanseatic League

|

|

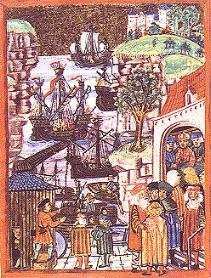

The foundations of the Hanseatic League (German: Hanse), an alliance of trading cities that for a time in the later Middle Ages and the Early Modern period maintained a trade monopoly over most of Northern Europe and the Baltic, can be seen as early as the 12th century, with the foundation of the new town of Lübeck in 1158/9 under the patronage of Henry the Lion of Saxony. Lübeck would become a central node in all the seatrade that linked the North Sea and the Baltic. There had been exploratory trading adventures, raids and piracy throughout this area— the sailors of Gotland sailed up rivers as far away as Novgorod— but there was no truly international economy before the Hanse (Braudel 1984).

Well before the term Hanse appeared in a document (1267), merchants in a given city began to form societies, or Hanse with the intention of trading with foreign cities, especially with the undeveloped Baltic, a source of timber, wax, resins, furs, even rye and wheat brought down on barges from the hinterland to port markets.

These societies worked to acquire special trade privileges for their members. For example, the merchants of Cologne (Köln) were able to convince Henry II of England to grant them special trading privileges and market rights in 1157. The Hanse creation, Lübeck, through which goods were transhipped between the North Sea and the Baltic gained the Imperial privilege of becoming an Imperial city in 1227, the only one east of the River Elbe.

Eventually, some of these cities began to form alliances with other cities in a loose network of mutual assistance. The chief city and linchpin remained Lübeck; with the first general Diet of the Hansa held there in 1356, the Hanseatic League had an official structure and could date its first official founding.

Lübeck's location on the Baltic provided access for trade with Scandinavia and Russia, putting it in direct competition with the Scandinavians who had previously controlled most of the Baltic trade routes. Competition was ended through a treaty with the traders of Gotland. Through this treaty, the Lübeck merchants also gained access to the Russian port of Novgorod, where they built a trading post or Kontor. Lübeck, which had access to the Baltic and North Sea fishing grounds, later formed an alliance with Hamburg, another trading city that controlled access to salt routes from Lüneburg. The allied cities were able to gain control over most of the salt fish trade. Other such alliances formed throughout the Holy Roman Empire. Over time, the network of alliances grew to include a flexible roster of 70 to 170 cities (Braudel 1984).

German colonists under strict Hanse supervision built numerous Hanse towns in the Baltic like Reval (Tallinn), Riga, and Dorpat (Tartu), some of which are still filled with buildings and bear the style of their Hanseatic days. Livonia (presently Estonia and Latvia) had its own Hanseatic parliament (diet), and all of its major towns were members of the Hanseatic League.

Eventually, the Hanse capital was moved to Gdańsk (Danzig), which was the main port for merchandise brought up the Vistula river. Other important cities which were members of the Hanse were Toruń (Thorn), Elbląg (Elbing), Königsberg, and Cracow.

The League was fluid in nature, but its members shared some traits. First, most of the Hanseatic League (or Hanse) cities either were founded as independent cities or gained independence through the collective bargaining power of the League. Independence was, however, limited; it meant that the cities owed allegiance directly to the respective Emperor, without any intermediate tie to the local nobility. Another similarity was that the cities were all strategically located along trade routes. In fact, at the height of its power in the late 1300s, the merchants of the Hanseatic League were able to use their economic clout (and sometimes their military might—trade routes needed protecting, and the League's ships were well-armed) to influence Imperial policy. The League also wielded power abroad: between 1368 and 1370, the League's ships fought against the Danes, and forced the Danish king to grant the League 15 percent of the profits from Danish trade (Treaty of Stralsund). Between 1392 and 1440 maritime trade of the League was in danger from raids of Victual Brothers and their descendants, a mighty brotherhood of privateers hired in 1392 by Albrecht of Mecklenburg against the Danish queen Margaret I.

Exclusive trade routes often came at a high price. In most foreign cities, the Hanse traders were confined to certain trading areas and to their own trading posts. They were seldom, if ever, allowed to interact with the local inhabitants, except in the matter of actual negotiation. Moreover, the power of the League was envied by many, merchant and noble alike. The very existence of the League and its privileges and monopolies created economic and social tensions that often crept over into rivalry between League members.

The Hansa was not spared the economic crises of the late 14th century, but its eventual rivals were the territorial states, whether new or revived, and not just in the west: Poland triumphed over the Teutonic Knights in 1466; Ivan the Terrible ended the entrepreneurial independence of Novgorod in 1476. New vehicles of credit imported from Italy outpaced the Hansa economy, where silver coin changed hands rather than bills of exchange.

By the late 16th century, the League imploded and was unable to deal with its own internal struggles, the social and political changes that accompanied the Reformation, the rise of Dutch and English merchants, and the incursion of the Ottoman Turks upon its trade routes and the Empire itself.

Despite its demise, several cities still maintain the link to the Hanseatic League. Even in the 21st century, the cities of Deventer, Kampen, Zutphen, Lübeck, Hamburg, Bremen, Rostock, Wismar, Stralsund, Greifswald and Anklam call themselves Hanse cities. For Lübeck in particular, this anachronistic tie to a glorious past remained especially important in the second half of the 20th century. Lübeck was also, as the other main cities, a "Free and Hanse City" as is still, for example Bremen. This privilege was removed by the Nazis after the Senat of Lübeck did not permit Adolf Hitler to speak in Lübeck during his election campaign. He held the speech in Bad Schwartau, a small village on the outskirts of Lübeck. He later referred to Lübeck always as "the small city close to Bad Schwartau".

| Contents |

Lists of former Hanse cities

In the list that follows, the role of these foreign merchant companies in the functioning of the city that was their host, in more than one sense is, as Fernand Braudel pointed out (The Perspective of the World p40), a telling criterion of the status of that city: "If he rules the roost in a given city or region, the foreign merchant is a sign of the [economic] inferiority of that city or region, compared with the economy of which he is the emissary or representative."

Members of the Hanseatic League

Hanse-built cities

Other Hanse-dominated cities

Cities with a Hanse community

|

|

(The reason the Russian cities like Novgorod, Pskov or Tver were listed here as Hanseatic is perhaps the strong presence of Hanseatic merchants in these cities. However, there is no way any German merchants or the Hanseatic League had anything to do with administering these Russian cities.)

External link

- Hanseatic Towns Network (http://www.hanse.org/)

Reference

- Braudel, Fernand, The Perspective of the World, vol. III of Civilization and Capitalism 1984

- E. Gee Nash. The Hansa. 1929 (Reprint. 1995 Edition, Barnes and Noble)cs:Hansa

da:Hanseforbundet de:Hanse et:Hansa Liit es:Liga Hanseática eo:Hansa Ligo fr:Hanse he:ברית ערי הנזה io:Hansa-uniono it:Lega Anseatica la:Hansa nl:Hanze ja:ハンザ同盟 nds:Hanse pl:Hanza ru:Ганзейский союз fi:Hansaliitto sv:Hansan zh:汉萨同盟