Greco-Buddhism

|

|

| Missing image Dharma_wheel_1.png Dharma wheel Buddhism |

| Culture |

| History |

| List of topics |

| People |

| By region and country |

| Schools and sects |

| Temples |

| Terms and concepts |

| Texts |

| Timeline |

Greco-Buddhism, sometimes spelled Græco-Buddhism, is the cultural syncretism between the culture of Classical Greece and Buddhism, which developed over a period of close to 800 years in Central Asia in the area corresponding to modern-day Afghanistan and Pakistan, between the 4th century BCE and the 5th century CE. Greco-Buddhism influenced the artistic (and, possibly, conceptual) development of Buddhism, and in particular Mahayana Buddhism, before it was adopted by Central and Northeastern Asia from the 1st century CE, ultimately spreading to China, Korea and Japan.

| Contents |

|

3.1 The Greek presence in Bactria (332 to 125 BCE) |

History

The interaction between Hellenistic Greece and Buddhism started when Alexander the Great conquered Asia Minor and Central Asia in 334 BCE, going as far as the Indus, thus establishing direct contact with India, the birthplace of Buddhism.

Alexander founded several cities in his new territories in the areas of the Oxus and Bactria, and Greek settlements further extended to the Khyber Pass, Gandhara (see Taxila) and the Punjab. These regions correspond to a unique geographical passageway between the Himalayas and the Hindu Kush mountains, through which most of the interaction between India and Central Asia took place, generating intense cultural exchange and trade.

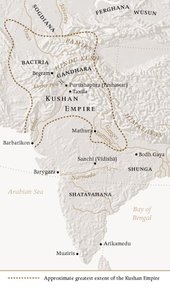

Following Alexander's death on June 10, 323 BCE, his Diadochi (generals) founded their own kingdoms in Asia Minor and Central Asia. General Seleucus set up the Seleucid Kingdom, which extended as far as India. Later, the Eastern part of the Seleucid Kingdom broke away to form the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom (3rd–2nd century BCE), followed by the Indo-Greek Kingdom (2nd–1st century BCE), and later still by the Kushan Empire (1st–3rd century CE).

The interaction of Greek and Buddhist cultures operated over several centuries until it ended in the 5th century CE with the invasions of the White Huns, and later the expansion of Islam.

See also: History of Buddhism

Artistic influences

Numerous works of Greco-Buddhist art display the intermixing of Greek and Buddhist influences, around such creation centers as Gandhara. The subject matter of Gandharan art was definitely Buddhist, while most motifs were of Western Asiatic or Hellenistic origin.

The anthropomorphic representation of the Buddha

MaraAssault.JPG

Although there is still some debate, the first anthropomorphic representations of the Buddha himself are often considered a result of the Greco-Buddhist interaction. Before this innovation, Buddhist art was "aniconic": the Buddha was only represented through his symbols (an empty throne, the Bodhi tree, the Buddha's footprints, the prayer wheel).

This reluctance towards anthropomorphic representations of the Buddha, and the sophisticated development of aniconic symbols to avoid it (even in narrative scenes where other human figures would appear), seem to be connected to one of the Buddha’s sayings, reported in the Digha Nikaya, that discouraged representations of himself after the extinction of his body.

Probably not feeling bound by these restrictions, and because of "their cult of form, the Greeks were the first to attempt a sculptural representation of the Buddha" (Linssen, "Zen Living"). In many parts of the Ancient World, the Greeks did develop syncretic divinities, that could become a common religious focus for populations with different traditions: a well-known example is the syncretic God Sarapis, introduced by Ptolemy I in Egypt, which combined aspects of Greek and Egyptian Gods. In India as well, it was only natural for the Greeks to create a single common divinity by combining the image of a Greek God-King (The Sun-God Apollo, or possibly the deified founder of the Indo-Greek Kingdom, Demetrius), with the traditional attributes of the Buddha.

Many of the stylistic elements in the representations of the Buddha point to Greek influence: the Greco-Roman toga-like wavy robe covering both shoulders (more exactly, its lighter version, the Greek himation), the contrapposto stance of the upright figures (see: 1st–2nd century Gandhara standing Buddhas [2] (http://faculty.maxwell.syr.edu/gaddis/HST210/Oct21/Gandhara%20Buddha.jpg) and [3] (http://www.kimbellart.org/database/images/jpg/AP1967_01.jpg)), the stylicized Mediterranean curly hair and top-knot apparently derived from the style of the Belvedere Apollo (http://www.artlex.com/ArtLex/h/images/hellenis_apolbelve.det.lg.JPG)(330 BCE), and the measured quality of the faces, all rendered with strong artistic realism (See: Greek art). A large quantity of sculptures combining Buddhist and purely Hellenistic styles and iconography were excavated at the Gandharan site of Hadda.

Greek artists were most probably the authors of these early representations of the Buddha, in particular the standing statues, which display "a realistic treatment of the folds and on some even a hint of modelled volume that characterizes the best Greek work. This is Classical or Hellenistic Greek, not archaizing Greek transmitted by Persia or Bactria, nor distinctively Roman" (Boardman).

The Greek stylistic influence on the representation of the Buddha, through its idealistic realism, also permitted a very accessible, understandable and attractive visualization of the ultimate state of enlightenment described by Buddhism, allowing it reach a wider audience: "One of the distinguishing features of the Gandharan school of art that emerged in north-west India is that it has been clearly influenced by the naturalism of the Classical Greek style. Thus, while these images still convey the inner peace that results from putting the Buddha's doctrine into practice, they also give us an impression of people who walked and talked, etc. and slept much as we do. I feel this is very important. These figures are inspiring because they do not only depict the goal, but also the sense that people like us can achieve it if we try" (The Dalai Lama, foreword to "Echoes of Alexander the Great", 2000).

During the following centuries, this anthropomorphic representation of the Buddha defined the canon of Buddhist art, but progressively evolved to incorporate more Indian and Asian elements.

A Hellenized Buddhist pantheon

Several other Buddhist deities may have been influenced by Greek gods. For example, Heracles with a lion-skin (who also happens to be the protector deity of Demetrius I) "served as an artistic model for Vajrapani, a protector of the Buddha" (Foltz, "Religions and the Silk Road") (See [4] (http://www.exoticindiaart.com/artimages/BuddhaImage/greece_sm.jpg) and[5] (http://faculty.maxwell.syr.edu/gaddis/HST210/Oct21/Heracles-Vajrapani.jpg)). In Japan, this expression further translated into the wrath-filled and muscular Niō guardian gods of the Buddha, standing today at the entrance of many Buddhist temples.

According to Katsumi Tanabe, professor at Chuo University, Japan (in "Alexander the Great.East-West cultural contact from Greece to Japan"), besides Vajrapani, Greek influence also appears in several other gods of the Mahayana pantheon, such as the Japanese Wind God Fujin (http://www2.aichi-med-u.ac.jp/german2/art/6-1a.jpg) inspired from the Greek Boreas through the Greco-Buddhist Wardo, or the mother deity Hariti (Kariteimo (http://www.shiga-miidera.or.jp/treasure/bi/img/jpg/04.jpg) and Kishibojin (http://p77g2t8o.hp.infoseek.co.jp/Kisimozin.jpg) in Japan) inspired by Tyche.

In addition, forms such as garland-bearing cherubs, vine scrolls, and such semi-human creatures as the centaur and triton, are part of the repertory of Hellenistic art introduced by Greco-Roman artists in the service of the Kushan court.

See also: Greco-Buddhist art, Buddhist art

Religious interactions

The length of the Greek presence in Central Asia and northern India provided opportunities for interaction, not only on the artistic, but also on the religious plane.

The Greek presence in Bactria (332 to 125 BCE)

When Alexander conquered the Bactrian and Gandharan regions, these areas may already have been under Buddhist influence.

According to a legend preserved in Pali, the language of the Theravada canon, two merchant brothers from Bactria, named Tapassu and Bhallika, visited the Buddha and became his disciples. They then returned to Bactria and built temples to the Buddha (Foltz).

Alexander established in this same area several cities (Ai-Khanoum, Begram) and an administration that were to last more than two centuries under the Seleucids and the Greco-Bactrians, all the time in direct contact with Indian territory. From 180 BCE, the Greco-Bactrians were further to expand into India, where they established the Indo-Greek kingdom.

In 125 BCE, the northern Indo-European Yuezhi nomads (the future Kushans, promoters of the Mahayana faith) took control of the Bactrian territory, and displaced the remaining Greco-Bactrians to the northwestern part of the Indian subcontinent. The Yuezhi underwent a process of Hellenization for more than a century, as exemplified by their coins and their adoption of the Greek alphabet.

The Mauryan empire (322–183 BCE)

The Indian emperor Chandragupta, founder of the Mauryan dynasty, re-conquered around 322 BCE the northwest Indian territory that had been lost to Alexander the Great. However, contacts were kept with his Greek neighbours in the Seleucid Empire, Chandragupta received the daughter of the Seleucid king Seleucus I after a peace treaty, and several Greeks, such as the historian Megasthenes, resided at the Mauryan court.

Chandragupta's son Bindusara also had a Greek ambassador at his court, named Deimachus (Strabo 1–70), and is known in Greek records for having requested a philosopher (a sophist) to the Seleucid king Antiochus I Soter (Athenaeus, "Deipnosophistae").

Chandragupta's grandson Asoka converted to the Buddhist faith and became a great proselytizer in the line of the traditional Pali canon of Theravada Buddhism, insisting on non-violence to humans and animals (ahimsa), and general precepts regulating the life of lay people.

According to the Edicts of Ashoka, set in stone, some of them written in Greek, he sent Buddhist emissaries to the Greek lands in Asia and as far as the Mediterranean. The edicts name each of the rulers of the Hellenic world at the time.

Ashoka also claims he converted to Buddhism Greek populations within his realm: "Here in the king's domain among the Greeks, the Kambojas, the Nabhakas, the Nabhapamkits, the Bhojas, the Pitinikas, the Andhras and the Palidas, everywhere people are following Beloved-of-the-Gods' instructions in Dhamma." Rock Edict Nb13 (S. Dhammika)

Finally, some of the emissaries of Ashoka, such as the famous Dharmaraksita, are described in Pali sources (the Mahavamsa, XII) as leading Greek Buddhist monks, active in Buddhist proselytism.

See also: Greco-Buddhist monasticism.

The Indo-Greek kingdom and Buddhism (180–1 BCE)

The Greco-Bactrians conquered northern India from 180 BCE, whence they are known as the Indo-Greeks. They controlled various areas of the northern Indian territory until 1 BCE.

Buddhism flourished under the Indo-Greek kings, and it has been suggested that their invasion of India was intended to protect the Buddhist faith from the religious persecutions of the new Indian dynasty of the Sungas (185–73 BCE) which had overthrown the Mauryans.

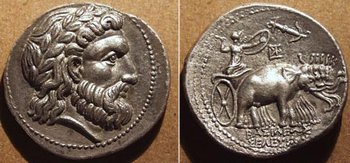

Coinage

Demetrius_I_of_Bactria.jpg

The coins of the Indo-Greek king Menander (reigned 160 to 135 BCE), found from Afghanistan to central India, bear the inscription "Saviour King Menander" in Greek on the front. Several Indo-Greek kings after Menander, such as Zoilos I, Strato I, Heliokles II, Theophilos, Peukolaos, Menander II and Archebios display on their coins the title of "Maharajasa Dharmika" (lit. "King of the Dharma") in the Prakrit language and in the Kharoshthi script.

Some of the coins of Menander I and Menander II incorporate the Buddhist symbol of the eight-spoked wheel, associated with the Greek symbols of victory, either the palm of victory, or the victory wreath handed over by the goddess Nike.

MenanderChakra.jpg

The ubiquitous symbol of the elephant in Indo-Greek coinage may also have been associated with Buddhism, as suggested by the parallel between coins of Antialcidas and Menander II, where the elephant in the coins of Antialcidas holds the same relationship to Zeus and Nike as the Buddhist wheel on the coins of Menander II. When the zoroastrian Indo-Parthians invaded northern India in the 1st century CE, they adopted a large part of the symbolism of Indo-Greek coinage, but refrained from ever using the elephant, suggesting that its meaning was not merely geographical.

IGMudras.JPG

Finally, after the reign of Menander I, several Indo-Greek rulers, such as Amyntas, King Nicias, Peukolaos, Hermaeus, Hippostratos and Menander II, depicted themselves or their Greek deities forming with the right hand a benediction gesture identical to the Buddhist vitarka mudra (thumb and index joined together, with other fingers extended), which in Buddhism signifies the transmission of Buddha's teaching.

Cities

According to Ptolemy, Greek cities were founded by the Greco-Bactrians in northern Pakistan. Menander established his capital in Sagala, today's Sialkot in Punjab, one of the centers of the blossoming Buddhist culture (Milinda Panha, Chap. I). A large Greek city built by Demetrius and rebuilt by Menander has been excavated at the archeological site of Sirkap near Taxila, where Buddhist stupas were standing side-by-side with Hindu and Greek temples, indicating religious tolerance and syncretism.

Scriptures

![A -style Buddhist in the Indo-Greek city of , northern , . It combines the sculptures of three temple-fronts: Greek (hidden from view, on the left), Hindu (center) and Buddhist (right). (See also wider view: [1] (http://www.web.virginia.edu/asianarc/public/taxila/eagle02.jpg)).](/encyclopedia/images/thumb/c/cf/250px-Sirkap13_d_headed_eagle.jpg)

Evidence of direct religious interaction between Greek and Buddhist thought during the period include the Milinda Panha, a Buddhist discourse in the platonic style, held between king Menander and the Buddhist monk Nagasena.

Also the Mahavamsa (Chap. XXIX) records that during Menander's reign, "a Greek Buddhist head monk" named Mahadharmaraksita led 30,000 Buddhist monks from "the Greek city of Alexander-of-the-Caucasus" (around 150km north of today's Kabul in Afghanistan), to Sri Lanka for the dedication of a stupa, indicating that Buddhism flourished in Menander's territory and that Greeks took a very active part in it.

Several Buddhist dedications by Greeks in India are recorded, such as that of the Greek meridarch (civil governor of a province) Theodorus, describing in Kharoshthi how he enshrined relics of the Buddha during the reign of Menander or his successor (Tarn, p.388).

Finally, Buddhist tradition recognizes Menander as one of the great benefactors of the faith, together with Asoka and Kanishka.

Buddhist manuscripts in cursive Greek have been found in Afghanistan, praising various Buddhas and including mentions of the Mahayana Lokesvara-raja Buddha (λωγοασφαροραζοβοδδο). These manuscripts have been dated later than the 2nd century CE. (Nicholas Sims-Williams, "A Bactrian Buddhist Manuscript").

The Mahayana movement probably began around the 1st century BCE in northwestern India, at the time and place of these interactions. According to most scholars, the main sutras of Mahayana were written after 100 BCE, when sectarian conflicts arose among Nikaya Buddhist sects regarding the humanity or super-humanity of the Buddha and questions of metaphysical essentialism, on which Greek thought may have had some influence: "It may have been a Greek-influenced and Greek-carried form of Buddhism that passed north and east along the Silk Road" (McEvilly, "The shape of ancient thought").

The Kushan empire (1st–3rd century CE)

The Kushans, one of the five tribes of the Yuezhi confederation settled in Bactria since around 125 BCE, invaded the northern parts of Pakistan and India from around 1 CE.

By that time they had already been in contact with Greek culture and the Indo-Greek kingdoms for more than a century. They used the Greek script to write their language. The absorption of Greek historical and mythological culture is suggested by Kushan sculptures representing Dyonisiac scenes or even the story of the Trojan horse (See: Kushan Trojan horse (http://faculty.maxwell.syr.edu/gaddis/HST210/Oct21/Gandhara%20Trojanhorse.jpg)), and it is probable that Greek communities remained under Kushan rule.

The Kushan king Kanishka, who honored Zoroastrian, Greek and Brahmanic deities as well as the Buddha and was famous for his religious syncretism, convened the Fourth Buddhist Council around 100 CE in Kashmir, which marked the official recognition of the pantheistic Mahayana Buddhism and its scission with Nikaya Buddhism. Some of Kanishka's coins bear the earliest representations of the Buddha on a coin (around 120 CE), in Hellenistic style and with the word "Boddo" in Greek script .

KanishkaCasketDrawing.jpg

Kanishka also had the original Gandhari vernacular, or Prakrit, Mahayana Buddhist texts translated into the high literary language of Sanskrit, "a turning point in the evolution of the Buddhist literary canon" (Foltz, Religions on the Silk Road)

The "Kanishka casket", dated to the first year of Kanishka's reign in 127 CE, was signed by a Greek artist named Agesilas, who oversaw work at Kanishka's stupas (caitya), confirming the direct involvement of Greeks with Buddhist realizations at such a late date.

The new syncretic form of Buddhism expanded fully into Eastern Asia soon after these events. The Kushan monk Lokaksema visited the Han Chinese court at Loyang in 178 CE, and worked there for ten years to make the first known translations of Mahayana texts into Chinese. The new faith later spread into Korea and Japan, and was itself at the origin of Zen.

Greco-Buddhism and the rise of the Mahayana

The geographical, cultural and historical context of the rise of Mahayana Buddhism during the 1st century BCE in northwestern India, all point to intense multi-cultural influences: "Key formative influences on the early development of the Mahayana and Pure Land movements, which became so much part of East Asian civilization, are to be sought in Buddhism's earlier encounters along the Silk Road" (Foltz, Religions on the Silk Road).

Conceptual influences

Mahayana is an inclusive faith characterized by the adoption of new texts, in addition to the traditional Pali canon, and a shift in the understanding of Buddhism. It goes beyond the traditional Theravada ideal of the release from suffering (dukkha) and personal enlightenment of the arhats, to elevate the Buddha to a God-like status, and to create a pantheon of quasi-divine Bodhisattvas devoting themselves to personal excellence, ultimate knowledge and the salvation of humanity. These concepts, together with the sophisticated philosophical system of the Mahayana faith, may have been influenced by the interaction of Greek and Buddhist thought:

The Buddha as an idealized man-god

The Buddha was elevated to a man-god status, represented in idealized human form: "One might regard the classical influence as including the general idea of representing a man-god in this purely human form, which was of course well familiar in the West, and it is very likely that the example of westerners' treatment of their gods was indeed an important factor in the innovation... The Buddha, the man-god, is in many ways far more like a Greek god than any other eastern deity, no less for the narrative cycle of his story and appearance of his standing figure than for his humanity" (Boardman, "The Diffusion of Classical Art in Antiquity" ).

The supra-mundane understanding of the Buddha and Bodhisattvas may have been a consequence of the Greek’s tendency to deify their rulers in the wake of Alexander’s reign: "The god- king concept brought by Alexander (...) may have fed into the developing bodhisattva concept, which involved the portrayal of the Buddha in Gandharan art with the face of the sun god, Apollo" (McEvilly, "The Shape of Ancient Thought").

The Bodhisattva as a Universal ideal of excellence

HaddaTypes.JPG

Greek influence has been suggested (Etienne Lamotte, cited in Williams) in the definition of the Bodhisattva ideal in the oldest Mahayana text, the "Perfection of Wisdom" or prajñā pāramitā literature, between the 1st century BCE and the 1st century CE in Northwestern India. These texts in particular redefine Buddhism around the universal Bodhisattva ideal, and its six central virtues of generosity, morality, patience, effort, meditation and, first and foremost, wisdom.

These qualities are reminiscent the Greek Stoicist philosophy, which may also have influenced the understanding of each individual as having the potential to reach excellence (Concept of Universal Buddha nature) and as being equally worthy of compassion (Compassion for all or “Karuna”, related to the Greek Universal loving kindness, “Philanthropia”). The Stoics had a “conviction in the essential equality of all humankind (...), which did not provide for superior or inferior, dominant and subordinate relations between states. From the ideal of equality there followed the Stoics' emphasis on virtue, conscience, duty, and absolute personal integrity" (Bentley, "Old World Encounters").

Philosophical influences

The close association between Greeks and Buddhism probably led to exchanges on the philosophical plane as well. Many of the early Mahayana theories of reality and knowledge can be related to Greek philosophical schools of thought. Mahayana Buddhism has been described as the “form of Buddhism which (regardless of how Hinduized its later forms became) seems to have originated in the Greco-Buddhist communities of India, through a conflation of the Greek Democritean-Sophistic-Skeptical tradition with the rudimentary and unformalized empirical and skeptical elements already present in early Buddhism” (McEvilly, "The Shape of Ancient Thought").

- In the Prajnaparamita, the rejection of the reality of passing phenomena as “empty, false and fleeting” can also be found in Greek Pyrrhonism.

- The distinction between conditioned and unconditioned being, and the denial of the reality of everyday experience in favour of an “unchanging and absolute ground of Being” is at the center of Platonism as well as Nagarjuna’s Madhyamika thought.

- The perception of ultimate reality was, for the Cynics as well as for the Madyamikas and Zen teachers after them, only accessible through a non-conceptual and non-verbal approach (Greek "Phronesis"), which alone allowed to get rid of ordinary conceptions.

- The mental attitude of equanimity and dispassionate outlook in front of events was also characteristic of the Cynics and Stoics, who called it "Apatheia".

Greco-Persian cosmological influences

One of the most popular themes of Greco-Buddhist art, the future Buddha Maitreya, has often been linked to the Iranian saviour figure Mitra, itself adopted as a Greek syncretic cult under the name Mithras. Maitreya pertains to the traditions of the “Second coming” of a Messiah and "echoes the qualities of the Zoroastrian Saoshyant and the Christian Messiah" (Foltz). The Buddha Amitabha (literally meaning “Infinite radiance”) with his Western paradisiacal "Pure Land" "seems to be understood as the Iranian god of light, equated with the sun" (Foltz). The very notion of paradise is a Persian invention (Old Persian: “Para Daisa”), which was probably relayed by the Greeks.

However, Mitra was also a solar deity of the Hindu Vedic Pantheon and Hindus have the notion of swarg, or the heavens.

Gandharan proselytism

Buddhist monks from the region of Gandhara, where Greco-Buddhism was most influential, played a key role in the development and the transmission of Buddhist ideas in the direction of northern Asia.

- Kushan monks, such as Lokaksema (c. 178 CE), travelled to the Chinese capital of Loyang, where they became the first translators of Mahayana Buddhist scriptures into Chinese. Central Asian and East Asian Buddhist monks appear to have maintained strong exchanges until around the 10th century, as indicated by frescos from the Tarim Basin.

- Two half-brothers from Gandhara, Asanga and Vasubandhu (4th century), created the Yogacara or "Mind-only" school of Mahayana Buddhism, which through one of its major texts, the Lankavatara Sutra, became a founding block of Mahayana, and particularly Zen, philosophy.

- In 485 CE, according to the Chinese historic treatise Liang Shu, five monks from Gandhara travelled to the country of Fusang ("The country of the extreme East" beyond the sea, probably eastern Japan, although some historians suggest the American Continent), where they introduced Buddhism:

- "Fusang is located to the east of China, 20,000 li (1,500 kilometers) east of the state of Da Han (itself east of the state of Wa in modern Kyushu, Japan). (...) In former times, the people of Fusang knew nothing of the Buddhist religion, but in the second year of Da Ming of the Song dynasty (485 CE), five monks from Kipin (Kabul region of Gandhara) travelled by ship to Fusang. They propagated Buddhist doctrine, circulated scriptures and drawings, and advised the people to relinquish worldly attachments. As a results the customs of Fusang changed" (Ch:"扶桑在大漢國東二萬餘里,地在中國之東(...)其俗舊無佛法,宋大明二年,罽賓國嘗有比丘五人游行至其國,流通佛法,經像,教令出家,風 俗遂改.", Liang Shu, 7th century CE).

- Bodhidharma, the founder of Zen, is described as a Central Asian Buddhist monk in the first Chinese references to him (Yan Xuan-Zhi, 547 CE), although later traditions describe him as coming from South India.

See also: Silk Road transmission of Buddhism

Intellectual influences in Asia

Through art and religion, the influence of Greco-Buddhism on the cultural make-up of Northern Asian countries, especially Korea and Japan, may have extended further into the intellectual area.

At the same time as Greco-Buddhist art and Mahayana schools of thought such as Zen were transmitted to northern Asia, central concepts of Hellenic culture such as virtue, excellence or quality may have been adopted by the cultures of Korea and Japan after a long diffusion among the Hellenized cities of Central Asia, to become a key part of their warrior and work ethics.

Greco-Buddhism and the West

In the direction of the West, the Greco-Buddhist syncretism may also have had some formative influence on the religions of the Mediterranean Basin.

Exchanges

Intense westward physical exchange at that time along the Silk Road is confirmed by the Roman craze for silk from the 1st century BCE to the point that the Senate issued, in vain, several edicts to prohibit the wearing of silk, on economic and moral grounds. This is attested by at least three significant authors:

- Strabo (64/ 63 BCE–c. 24 CE).

- Seneca the Younger (c. 3 BCE–65 CE).

- Pliny the Elder (23–79 CE).

The aforementioned Strabo and Plutarch (c. 45–125 CE) wrote about king Menander, confirming that information was circulating throughout the Hellenistic world.

Religious influences

Although the philosophical systems of Buddhism and Christianity have evolved in rather different ways, the moral precepts advocated by Buddhism from the time of Ashoka through his edicts do have a very strong similarity with the Christian moral precepts developed more than two centuries later: respect for life, respect for the weak, rejection of violence, pardon to sinners, tolerance.

These similarities may indicate the propagation of Buddhist ideals into the Western World, the Greeks acting as intermediaries and religious syncretists: "Scholars have often considered the possibility that Buddhism influenced the early development of Christianity. They have drawn attention to many parallels concerning the births, lives, doctrines, and deaths of the Buddha and Jesus" (Bentley, "Old World Encounters"). The story of the birth of the Buddha was well known in the West, and possibly influenced the story of the birth of Jesus: Saint Jerome (4th century CE) mentions the birth of the Buddha, who he says "was born from the side of a virgin". Also a fragment of Archelaos of Carrha (278 CE) mentions the Buddha's virgin-birth.

The main Greek cities of the Middle-East happen to have played a key role in the development of Christianity, such as Antioch and especially Alexandria, and “it was later in this very place that some of the most active centers of Christianity were established” (Robert Linssen, “Zen living”).

See also

External links

- UNESCO: Threatened Greco-Buddhist art (http://www.unesco.org/bpi/eng/unescopress/2001/taliban-crisis.shtml)

- Alexander the Great: East-West Cultural contacts from Greece to Japan (Japanese) (http://event.yomiuri.co.jp/2003/S0172/alex_works.htm)

- Origin of the Buddha image (http://www.exoticindiaart.com/article/buddhaimage)

- Evolution of the Buddha image (http://www.exoticindiaart.com/article/lordbuddha)

- The Hellenistic age (http://faculty.maxwell.syr.edu/gaddis/HST210/Oct21/Default.htm)

- The Kanishka Buddhist coins (http://www.bpmurphy.com/COTW/week2.htm)

References

- "Religions and the Silk Road" by Richard C. Foltz (St. Martin's Press, 1999) ISBN 0312233388

- "The Diffusion of Classical Art in Antiquity" by John Boardman (Princeton University Press, 1994) ISBN 0691036802

- "The Shape of Ancient Thought. Comparative studies in Greek and Indian Philosophies" by Thomas McEvilley (Allworth Press and the School of Visual Arts, 2002) ISBN 1581152035

- "Old World Encounters. Cross-cultural contacts and exchanges in pre-modern times" by Jerry H.Bentley (Oxford University Press, 1993) ISBN 0195076397

- "Alexander the Great: East-West Cultural contacts from Greece to Japan" (NHK and Tokyo National Museum, 2003)

- "Living Zen" by Robert Linssen (Grove Press New York, 1958) ISBN 0802131360

- "Echoes of Alexander the Great: Silk route portraits from Gandhara" by Marian Wenzel, with a foreword by the Dalai Lama (Eklisa Anstalt, 2000) ISBN 1588860140

- "The Edicts of King Asoka: An English Rendering" by Ven. S. Dhammika (The Wheel Publication No. 386/387) ISBN 9552401046

- "Mahayana Buddhism, The Doctrinal Foundations", Paul Williams, Routledge, ISBN 0415025370

- "The Greeks in Bactria and India", W.W. Tarn, South Asia Books, ISBN 8121502209bg:гръко-будизъм