Iconography

|

|

Salvatormundi.jpg

It has been said “A picture is worth a thousand words”, and so it is that iconography is the traditional art of portraying figures in pigment that symbolically mean more than a simple depiction of the person involved.

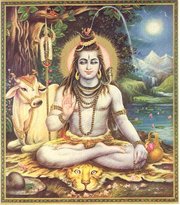

Icons have been used by many different religions including Hinduism, Buddhism, and Christianity. In icons where a portraiture is intended, the emphasis on the spiritual aspects of the person are more important than the actual physical appearance of the person, though, in the case of traditional Christian iconography, the icons of Christ, the Virgin Mary, and the saints have a consistency that leads one to believe that there are probably striking similarities between the image depicted and how the person really looked. Traditionally the Eastern Orthodox Christians believe the first icons of Christ and the Virgin Mary to have been painted by St Luke, who probably knew them. In the case of the various Hindu gods, however, almost everything is considered symbolism. The figures are blue-skinned (the color of heaven) with multiple arms holding various symbols depicting aspects of the god (the drums of change, the flower of new life, the fire of destruction, etc.). The many heads, eyes, feet, and arms do not have to be taken literally.

In early Christian history it would seem that iconography was generally accepted, however, certain excesses and misunderstandings about the nature and substance of icons began to arise around the 6th century. Questions concerning the prohibition in scriptures concerning graven images split the church into two groups, the Iconoclasts (against icons) and the Iconodules (for icons). After much debate at the 7th ecumenical council, held in Nicaea in 787 CE, the Church (Eastern Orthodox and Roman Catholic) upheld the use of icons as an integral part of Christian tradition. To distinguish the veneration of icons from the worship of idols the concept was born that the praise and veneration shown to the icon passes over to the archetype. Thus to kiss an icon of Christ was to show love towards Christ Jesus himself, not the wood and paint making up the physical substance of the icon. A more modern illustration of this concept might be that the photographs a person keeps (and even loves) have nothing to do with the photographic paper or film but rather the persons and events depicted. It was also reckoned that the prohibition in the Old Testament scriptures against the material depiction of the immaterial God is overturned in the New Testament when God takes material flesh in the form of Jesus Christ.

While in the West the trend toward “art” has lead to very “worldly” paintings of holy figures by “worldly” artists, in Eastern Orthodoxy, the artist must be willing to adopt an almost monastic level of ascetic practice in order to correctly "see" the spiritual world he is depicting. There is also no room for personal interpretation in the subject matter. The church has established an extensive set of rules and guidelines to be used for painting icons, both in general and for particular icons. Icons communicate theological truth, therefore, their composition must be as carefully executed as the writing of theological treatises. Because the icon conveys so much information through its clever symbolism, Eastern Orthodox theologians often find it useful to refer to a particular icon when making a point, just as they might cite a document written by an earlier theologian or council. Monks often carry out the responsibility of painting icons as they are most suited to the task. Artistic talent is secondary to spiritual training. Fasting and continual prayer are considered a requirement of the iconographer in order to correctly depict the spiritual realm. For the Orthodox, icons serve as windows into heaven. The interiors of Orthodox Churches are often completely covered in icons. In this way the congregation see the Gospel and the lives of the saints in a very clear and complete way. Their usefulness cannot be matched by written text. Because the honor shown them passes over to the archetype, icons are kissed, carried in procession, and venerated.

Symbolism in icons

In Eastern Orthodoxy, color has meaning as well as form. Gold represents the radiance of Heaven, or the Uncreated light of God; red, the blood of martyrs, or Divinity on icons of Christ or icons of [[Virgin Mary|Mary]. Blue is the color of purity, or, on the aforementioned, humanity, white is also used to depict purity. Often the symbolism is slightly different depending on the roots of the tradition, whether Russian, Greek, or Syrian. Symbols abound. Mountains in the background usually mean the scene took place outside while buildings and walls mean the event took place inside. St George and St Demetrios are shown slaying dragons, a symbol for sin and temptation. St Marina shows her fortitude and strength against sin by gripping the devil by his hair. The wings of angels (a symbol for messenger), the wheel on which St Catherine was tortured, and the axe, laid close to the roots in the icon of St John the forerunner are all examples of the symbolism found in icons.

Light is also an interesting part of icons. The figures in icons are painted in such a way that it seems light is coming from within. In addition a nimbus of light is shown around the heads of holy individuals while it is absent from those who are not Christians. This nimbus is similar to the halo of Western art, except that it is never a ring floating above the head, but seems rather to be a sphere of light, a perfect circle no matter which way the head of the figure points.

As a general rule, the figures in icons are shown with serene, passionless faces, never smiling or angry. This stylized appearance is often mistaken for sadness, but it is intended to show their seriousness, and their freedom from the vicissitudes of emotion. Figures are almost always facing outward toward the viewer, though sometimes they may be looking at another figure in the icon. At the most, a 3/4s view of the face is seen, never profile of back of the head.