Continuation War

|

|

The Continuation War was fought between Finland and the Soviet Union during World War II; from the Soviet bombing attacks on June 25, 1941, to cease-fire September 4, 1944 (on the Finnish side) and September 5 (on the Soviet side). The United Kingdom declared war on Finland on December 6, 1941, but didn't participate actively. Material support from, and military cooperation with, Nazi Germany was critical for Finland's struggle with its larger neighbour. The war was formally concluded by the Paris peace treaty of 1947.

The Continuation War (jatkosota in Finnish, fortsättningskriget in Swedish) is so named because the Finns view it as a continuation of the Winter War (November 30, 1939, to March 12, 1940). Seen from a Russian perspective, it was merely one of the fronts of the Great Patriotic War. The war was, however, considered separate from the World War by Finland and the Soviet Union – an understanding not quite appreciated by the political leadership in Nazi Germany, Finland's chief supporter.

Introduction

Although the Continuation War was fought in the periphery of World War II and the engaged troops were relatively few, the history of this war is intriguing as it challenges much of the conventional wisdom on the World War, and the popular theory that democratic countries don't wage war against each other. Technically, war was declared. In practice it was trivial. There was no engagement between combatant troops.

During the conflict, Finland acted in concert with Nazi Germany against the Soviet Union, which in turn was allied with Britain and, for most of the period, the United States. Democratic Finland's association with Nazi Germany was, and remains, controversial in the European democracies threatened and occupied by the Nazis. It was only as a last resort to protect herself from Soviet aggression. Memories of the 1939 Winter War with the Soviets, and the inability of the Allies to support the Finns were the motivation for the alliance with Nazi Germany.

The issue was less controversial in Finland, and in hindsight a relatively broad Finnish consensus asserts that the Finns as a people would most likely not have survived the war without cooperating with Nazi Germany. While conventional wisdom among Finns who grew up in the 1960s–70s depicted the Continuation War as a Finnish mistake, the Collapse of the Soviet Union led to access to Soviet sources revealing the Kremlin's firm determination to put all of Finland under Soviet rule. The same people who in the 1970s were convinced of Finland's guilt for the Great Patriotic War nowadays assert that there was really nothing Finland could have done to avoid the Winter War and the Continuation War — at least not in the last years before the wars.

Major events of World War II, and the tides of war in general, had significant impact on the course of the Continuation War:

- Nazi Germany's invasion of the Soviet Union (Operation Barbarossa) is closely connected to the Continuation War's beginning.

- The Allied invasion of France (Battle of Normandy) was coordinated with the Soviet major offensive against Finland (June 9–July 15, 1944), leading to a five week long alliance between democratic Finland and Nazi Germany (June 26 to August 4, 1944).

- The subsequent US/Soviet race to Berlin brought about the end of the Continuation War by rendering Northern Europe irrelevant.

Aims of war

Finland's main goal during World War II was, although nowhere literally stated, to survive the war as an independent country, capable of maintaining its sovereignty in a politically hostile environment. Specifically for the Continuation War, Finland aimed at reversing its territorial losses under the March 1940 Moscow Peace Treaty and by extending the territory further east, to guarantee the survival of the Finnic brethren in East-Karelia — thus in effect aiming at creating a Greater Finland, as advocated by vociferous right-wing groups. Finland's exertion during the World War was, in the former respect, successful, although the price was high in war casualties, reparation payments, territorial loss, bruised international reputation and subsequent adaptation to Soviet international perspectives.

The Soviet Union's war goals are harder to assess due to the secretive nature of the Stalinist Soviet Union. Intelligence, as interrogations of POWs, clearly indicated military control of all of Finland's territory as the immediate military goal in both the Winter War and the Continuation War. This is congruent with a (postulated) Russian long-term strategic goal of securing ice-free harbours at the Atlantic and the North Sea. The Soviet Union of the 1930s was however a militarily weak power, and it can be argued that all of her policies up to the Continuation War are best explained as defensive measures (however by offensive means): the sharing of Poland with Nazi Germany, the annexation of the Baltic states and the attempted invasion of Finland in the Winter War can all be seen as elements in the construction of a security zone between the perceived threat from the capitalist powers of Western Europe and the Communist Soviet Union – similar to the post-war establishment of Soviet satellite states in the Warsaw Pact countries and the Agreement of Friendship, Cooperation, and Mutual Assistance concluded with post-war Finland. Accordingly, after Nazi Germany's attack on the Soviet Union (Operation Barbarossa, June 22, 1941), the Red Army's attack on Finland, harbouring not yet unleashed German forces, can be seen as a pre-emptive or preventive attack aiming to protect Russian civilians and troops: through control of Finland's territory, the threat against Leningrad (i.e. the old imperial capital Saint Petersburg) and the important harbour in Murmansk was to be fended off.

Background

Before World War II

Although East Karelia has never been part of Finland, a majority of its inhabitants were Finnic people; and cultural ties, trade, and cross-border marriages were common before World War I and Finnish independence. Indicative of this is that the majority of poems in the Kalevala were collected from the backwaters of East Karelia where Swedish and Slavic influences have been lowest. So it was no surprise that after the independence was declared, voices arose advocating the annexation of East Karelia in order to rescue its inhabitants from Bolshevist oppression.

Immediately after the Civil War in Finland a group of enthusiasts formed two military expeditions, Aunus and Viena expeditions, to drive the Bolshevist Russian army from East Karelia, but they were defeated and the expedition had to return Finland. Thus in the Treaty of Tartu, the Petsamo region was incorporated into Finland instead of East Karelia. The idea lived still in the Akateeminen Karjala-Seura (Academic Karelia Society, AKS), the most influential university student organization before World War II, where numerous contemporary and future political and economic figures participated, as members or alumni. Official Finland raised the question of East Karelia several times in the League of Nations, demanding a similar referendum for the future of the region as had been arranged in Saarland, Silesia and Schleswig. The Soviet Union countered these demands by forming the autonomous Republic of Karelia 1923.

In non-leftist circles, Imperial Germany's role in the "White" government's victory over rebellious Socialists during the Civil War in Finland was commemorated, although the majority of them preferred Britain or the Scandinavian countries over Germany. The right extremist Lapua Movement was created to finally make an end to the communists, and it saw the contemporary brand of European democracy as too soft on Communism, and considered Fascist Italy as a model how left extremism should be eradicated. The Lapua Movement lost its support base due to its illegal methods employed against moderate politicians, and it was banned in 1932 after a failed rebellion in Mäntsälä. The right wing extremism continued to live in Isänmaallinen Kansanliike (Patriotic People's Movement, IKL) which had 14 seats out of the 200 representatives in the Finnish parliament. After the Nazi Party took power in Germany, IKL became a strong supporter for an alliance with the "New Germany", which cracked down on all open Communist activity in Germany.

The security policy of independent Finland turned first towards a cordon sanitaire, where the newly independent nations of Poland, the Baltic Republics and Finland should form a defensive alliance against Russia, but, after negotiations collapsed, Finland turned to the League of Nations for security. Contacts with the Scandinavian countries were also nurtured, but questions about the control of Ahvenanmaa (Åland) and minority languages in Finland and northern Scandinavia prevented success. In 1932, Finland and Soviet Union signed a non-aggression pact, but even contemporary analysts considered it worthless.

The Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact and the Winter War

The Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact clarified Soviet–German relations and enabled Soviet pressure against the small Baltic republics and Finland, allegedly in order for the Soviet Union to better her own strategic position in Eastern Europe in preparation for a possible widening of the war. The Baltic republics soon gave in to Soviet demands of bases and troop transfer rights, but Finland continued to refuse. As diplomatic pressure had failed, it came time to use arms, and on November 30, 1939, the Soviet Union began an invasion of Finland — the Winter War.

The Winter War produced in Finns a rude awakening to international politics. The condemnations of the League of Nations and countries all over the world seemed to have no effect on Soviet policy. Sweden allowed volunteers to join Finnish army, but did not send regular troops or its air force, and in the end did not allow Franco-British troop transfer through its region. France and Britain promised to send combat troops, but when their plans were examined, only a small fraction of those were destined for Finland. To the right wing extremists, it was a shock to notice that Nazi Germany did not help at all, but even blocked all material help from other countries as well.

The Moscow Peace Treaty, which ended the Winter War, was perceived as a great injustice. It seemed as if the losses at the negotiation table, including Finland's second largest city, Viipuri (Vyborg), had been worse than on the battlefield.[1] (http://www.winterwar.com/War%27sEnd.htm) A fifth of the country's industrial capacity had been lost. Of the twelve percent of Finland's population who lived there, only a few hundred remained, the remaining 420,000 moving to the Finnish side of the border. Also, eleven percent of Finnish agricultural soil was lost, the loss made more severe because it was the best Finland had.

After the Moscow Peace Treaty

The Moscow Peace Treaty, signed on March 12, 1940, was a veritable shock for the Finns. It was perceived as the ultimate proof of failure for Finland's foreign policy of the 1930s, that was based on multilateral guarantees for support from culturally and ideologically akin countries, first in the world order established by the League of Nations, and later from the Oslo group and Scandinavia. The immediate response was to broaden and intensify this policy. Formal binding bilateral treaties were now sought where Finland formerly had relied on goodwill and national friendship, and the formerly frosty relations to ideological adversaries, as the Soviet Union and the Third Reich, had necessarily to be eased.

Closer and improved relations were sought particularly with:

- Sweden and Norway

- the United Kingdom

- the Soviet Union

- the Third Reich

With exception for the case of Nazi Germany, all of these attempts turned out to meet critical obstacles — either due to Moscow's fear that Finland would slide out of the Soviet sphere of influence or due to general dynamics of the world war.

Interim peace

Public opinion in Finland longed for the re-acquisition of the homes of the 12% of Finland's population who had been forced to leave Finnish Karelia in haste, and put their hope to the peace conference that was generally assumed to come to follow the World War. The term Välirauha ("Interim peace") hence became popular at once after the harsh peace was announced.

To protest the Moscow Peace Treaty, two ministers resigned and Prime Minister Ryti was forced to form a new cabinet right away. To achieve better national consensus, all parties except the right extremist IKL participated in the cabinet.

The most difficult post to fill was that of Foreign Minister, for which Ryti and Mannerheim first thought of Finland's ambassador to London G. A. Gripenberg, but as he believed himself to be too unpopular in Berlin, Rolf Witting, who was less British-oriented and more suitable to achieve improved relations with Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union, was selected.

Attempted Nordic Defence Alliance

During the last days of war, Väinö Tanner and Per Albin Hansson had mentioned the possibility of a Nordic Defence Alliance, possibly including also Norway and Denmark, to stabilize the situation in the region. On March 15, this plan was published for discussion in the parliaments. However, on March 29 the Soviet Union declared that an alliance would be in breach of the Moscow Peace Treaty, stalling the plan, and Germany's invasion of Denmark and Norway killed even the option of a smaller Scandinavian Defence Alliance, that would benefit Finland also if she wasn't a party to it.

Re-armaments

Although the peace treaty was signed, the state of war was not revoked because of the widening world war, the difficult food supply situation, and the poor shape of the Finnish military. Censorship was not abolished but was used to suppress critics of the Moscow peace treaty and the most blatantly anti-Soviet comments.

The continued state of war made it possible for President Kyösti Kallio to ask Field Marshal Mannerheim to remain commander-in-chief and supervise the reorganization of Finland's Armed Forces and the fortification of the new border, a task that was critically important in the unruly times. Within a week after the peace treaty was signed, the fortification works were started along the 1200 km long Salpalinja ("the Bolt Line"), where the focus was between the Gulf of Finland and Lake Saimaa.

During the summer and autumn, Finland received material purchased and donated during and immediately after the Winter War, but it took several months before Mannerheim was able to present a somewhat positive assessment of the state of the army. Military expenditures rose in 1940 to 45% of Finland's state budget. Military purchases were prioritised over civilian needs. Mannerheim's position and the continued state of war enabled an efficient management of the military, but it created an unfortunate parallel government that from time to time clashed with the structures of civilian government.

March 13, the same day when Moscow Peace Treaty came into an effect, British Ministry of Economic Warfare (MEW) asked Foreign Office to start negotiations with Finland as soon as possible to secure positive relations to Finland. Undersecretary of MEW, Charles Hambro was authorized to form the war trade treaty with Finland, and he traveled to Helsinki April 7. He had already had exchanged letters with Ryti, and they reached quickly to the basic understanding of the contents of the treaty. Finns were eager to start trade, and from the first meeting the preliminary treaty was created, which Finns accepted immediately, but Hambro needed the approval of his superiors and that it would be considered official immediately until the final treaty was negotiated. In the treaty Finland gave control of her strategic material exports to Britain in exchange of armaments and other necessary materials.

Next day, German attack to Norway made the treaty obsolete as England canceled all trade to the region.

Denmark and Norway occupied

After Nazi Germany's assault on Scandinavia on April 9, 1940, Operation Weserübung, Finland was physically isolated from her traditional trade markets in the West. Sea routes to and from Finland were now controlled by the Kriegsmarine. The outlet of the Baltic sea was blockaded, and in the far north Finland's route to the world was an arctic dirt road from Rovaniemi to the ice-free harbour of Petsamo, from where the ships had to pass a long stretch of German-occupied Norwegian coast by the Arctic Ocean. Finland, like Sweden, was spared occupation but encircled by Nazi Germany and Soviet Union.

Especially damaging was the loss of fertilizer imports, that, together with the loss of arable land ceded in the Moscow Peace, the loss of cattle during the hasty evacuation after the Winter War, and the unfavourable weather in the summer of 1940, resulted in a drastic fall of foodstuff production to less than two thirds of what was Finland's estimated need. Some of the deficit could be purchased from Sweden and some from the Soviet Union, although delayed deliverances were then a means to exert pressure on Finland. In this situation, Finland had no alternative than to turn to Germany for help.

Finland seeks German rapprochement

Germany has traditionally been a counterweight to Russia in Baltic region, and despite the fact that Hitler's Third Reich had acquiesced with the invader, Finland perceived some value in also seeking warmer relations in that direction. After the German occupation of Norway, and particularly after the Allied evacuation from northern Norway, the relative importance of a German rapprochement increased. Finland had queried about the possibility of buying arms from Germany on May 9, but Germany refused to even discuss the matter.

From May 1940, Finland pursued a campaign to re-establish the good relations with Germany that had soured in the last year of the 1930's. Finland rested her hope in the fragility of the Nazi–Soviet bond, and in the many personal friendships between Finnish and German athletes, scientists, industrialists, and military officers. A part of that policy was accrediting the energetic Toivo Mikael Kivimäki as ambassador in Berlin in June 1940. The Finnish mass media not only refrained from criticism of Nazi Germany, but also took active part in this campaign. Dissent was censored. Seen from Berlin, this looked like a refreshing contrast to the annoyingly anti-Nazi press in Sweden.

After the fall of France, in late June, the Finnish ambassador in Stockholm heard from the diplomatic sources that Britain could soon be forced to negotiate peace with Germany. The experience from World War I emphasized the importance of close and friendly relations with the victors, and accordingly the courting of Nazi Germany was stepped up still further.

The first crack in the German coldness vis-ą-vis Finland was registered in late July, when Ludwig Weissauer, a secret representative of the German Foreign Minister, visited Finland and queried Mannerheim and Ryti about Finland's willingness to defend the country against the Soviet Union. Mannerheim estimated the Finnish army could last a few weeks without more arms. Weissauer left without any promises.

Continued Soviet pressure

The implementation of the Moscow Peace Treaty created problems due to the Soviet Vae Victis-mentality. Border arrangements in the Enso industrial area, which even Soviet members of the border commission considered to be on the Finnish side of the border, the forced return of evacuated machinery, locomotives, and rail cars; and inflexibility on questions which could have eased hardships created by the new border, such as fishing rights and the usage of Saimaa Canal merely served to heighten distrust about the objectives of the Soviet Union.

The Soviet attitude was personified in the new ambassador to Helsinki, Ivan Zotov. He behaved undiplomatically and had a stiff-necked drive to advance Soviet interests, real or imagined, in Finland. During the summer and autumn he recommended several times in his reports to the Soviet Foreign Office that Finland ought to be finished off and wholly annexed by the Soviet Union.

On June 23, the Soviet Union proposed that Finland should revoke Petsamo mining rights from the British–Canadian company and transfer them to the Soviet Union, and also grant the Soviet Union rights to handle security in the area. On June 27, Moscow demanded either demilitarization or a joint fortification effort in Åland. After Sweden had signed the troop transfer agreement with Germany on July 8, Soviet Foreign Minister Molotov demanded similar rights for a Soviet troop transit to Hanko on July 9. The transfer rights were given on September 6, and demilitarization of Åland was agreed on October 11, but negotiations on Petsamo continued to drag on, with Finnish negotiators stalling as much as possible.

The Communist Party was so discredited in the Winter War that it never managed to recuperate between the wars. Instead, on May 22, the "Peace and Friendship Society of Finland and Soviet Union" (SNS) was created, and it actively propagated Soviet viewpoints. Ambassador Zotov had very close contacts with the SNS by holding weekly meetings with the SNS leadership in the Soviet embassy and having Soviet diplomats participating in SNS board meetings. The SNS started by criticizing the government and military, and gained around 35,000 members at maximum. Emboldened by its success, it started organizing almost daily violent demonstrations during the first half of August which were supported politically by Zotov and a press campaign in Leningrad. The government reacted forcefully and arrested leading members of the society which ended the demonstrations in spite of Zotov's and Molotov's protests. The SNS was finally outlawed in December 1940.

The Soviet Union demanded that Väinö Tanner be discharged from the cabinet because of his anti-Soviet stance and he had to resign August 15. Ambassador Zotov further demanded the resignation of both the Minister of Social Affairs Karl-August Fagerholm because he had called the SNS a Fifth column in a public speech, and the Minister of Interior Affairs Ernst von Born, who was responsible for police and led the crackdown of the SNS, but they retained their places in the cabinet after Ryti delivered a radio speech in which he stated the willingness of his government to improve relations between Finland and the Soviet Union.

President Kallio suffered a stroke on August 28, after which he was unable to work, but when he presented his resignation November 27, the Soviet Union reacted by announcing that if Mannerheim, Tanner, Kivimäki, Svinhufvud or someone of their ilk were chosen president, it would be considered a breach of the Moscow peace treaty.

All of this reminded the public heavily of how the Baltic Republics had been occupied and annexed only a few months earlier. So it was no wonder that the average Finn feared that the Winter War had produced only a short delay of the same fate.

British disregard

Compared to the early spring, during the summer of 1940, Finland wasn't high in importance in British foreign policy. To gain support from the Soviet Union, Britain had appointed Sir Stafford Cripps, from the left wing of the Labour Party, ambassador to Moscow. He had openly supported the Terijoki Government during the Winter War and he wondered to ambassador Paasikivi 'didn't the Finns really want to follow Baltic Republics and join the Soviet Union?'. He also dismissively called president Kallio "Kulak" and Nordic social democracy "reactionary". The British Foreign Office had to apologize for his language to ambassador Gripenberg.

Britain opposed Finnish-Swedish cooperation and provided support for the Soviet Union to scuttle the initiative, until it became apparent in late March 1941 that it had driven Finland in the direction of the Germans, but by then it was already too late. Finnish foreign trade was another critical issue as it was dependent on British navycerts and the Ministry of Economic Warfare was extremely strict when issuing those so that even Finnish trade (and relations) with the Soviet Union suffered from it.

During the nickel negotiations the Foreign Office pressured the license owning British-Canadian company to "temporarily" release the license and offered diplomatic support to Soviet attempts to gain control of the mine with the precondition that no ore would be shipped to Germany.

Improved relations with Nazi Germany

Unbeknownst to Finland, Adolf Hitler had started to plan his forthcoming invasion of the Soviet Union (Operation Barbarossa) now when France had collapsed. He had not been interested in Finland before the Winter War, but now he saw the value of Finland as an operating base, and perhaps also the military value of the Finnish army. In the first weeks of August, German fears of a likely immediate Russian attack on Finland caused Hitler to free the arms embargo. The arms deliveries stopped under the Winter War were resumed.

The next visitor from Germany came on August 18, when a representative of Hermann Göring, arms dealer Joseph Veltjens, arrived. He negotiated with Ryti and Mannerheim about German troop transfer rights between Finnmark in Northern Norway and ports of Gulf of Bothnia in exchange for arms and other material. At first these arms shipments were transferred via Sweden, but later they came directly to Finland. For the Third Reich, this was a breach of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, as well as it for Finland was a material breach of the Moscow Peace Treaty that in fact was chiefly targeted against cooperation between Germany and Finland. It has in retrospect been disputed whether the ailing President Kallio was informed.[2] (http://www.mannerheim.fi/10_ylip/e_kkulku.htm) Possibly Kallio's health collapsed before he could be confidentially briefed.

From the campaign to ease the Third Reich's coldness towards Finland, it seemed a natural development to also promote closer relations and cooperation. Not the least since the much disliked Moscow Peace Treaty in clear language tried to persuade the Finns not to do exactly that. Propaganda in the censured press contributed to Finland's international re-orientation — although with very measured means.

Soviet negotiators had insisted that the troop transfer agreement (to Hanko) should not be published for parliamentary discussion or voting. This precedent made it easy for the Finnish government to keep a troop transfer agreement with the Germans secret until the first German troops arrived at the port of Vaasa on September 21. The arrival of German troops produced much relief to the insecurity of average Finns, and was largely approved. Most contrary voices opposed more the way the agreement was negotiated than the transfer itself, although the Finnish people knew only the barest details of the agreements with the Third Reich. The presence of German troops was seen as a deterrent for further Soviet threats and a counterbalance to the Soviet troop transfer right. The German troop transfer agreement was augmented November 21 allowing the transfer of wounded, and soldiers on leave, via Turku. Germans arrived and established quarters, depots, and bases along the rail lines from Vaasa and Oulu to Ylitornio and Rovaniemi, and from there along the roads via Karesuvanto and Kilpisjärvi or Ivalo and Petsamo to Skibotten and Kirkenes in northern Norway. Also roadwork for improving winter road between Karesuvanto and Skibotten and totally new road from Ivalo to Karasjok were discussed and later financed by Germans.

Ryti, Mannerheim, Minister of Defence Walden and chief of staff Heinrichs decided October 23 that information concerning Finnish defence plans of Lappland could be given to the Wehrmacht to gain goodwill, even with the risk that they could be forwarded to the Soviet Union.

When Soviet Foreign Minister Molotov visited Berlin on November 12, he demanded that Germany stop supporting Finland, and the right to handle Finland in a similar way to Baltic states, but Hitler demanded that there should be no new military activities in Northern Europe before summer. Through unofficial channels, Finnish representatives were informed that "Finnish leaders can sleep peacefully, Hitler has opened his umbrella over Finland."

Attempted Defence Union with Sweden

On August 19, a new initiative was launched for co-operation between Sweden and Finland. It called for a union of the two states in exchange for a Finnish declaration of satisfaction with the current borders. The plans were primarily championed by the Swedish Foreign Minister, Christian Günther, and Conservative party leader Gösta Bagge, Education Minister in Stockholm. They had to counter increasing anti-Swedish opinions in Finland; and in Sweden, Liberal and Socialist suspicions against what was seen as right-wing dominance in Finland. One of the chief objectives of the plan was to ensure greatest possible liberty for Sweden and Finland in a presumed post-war Europa totally dominated by Nazi Germany. In Sweden, political opponents criticized the necessary adaptations to the Nazis; in Finland, the resistance centred on the loss of sovereignty and influence — and the acceptance of the loss of Finnish Karelia. However, the general feeling of Finland's dire and deteriorating position quieted many critics.

The official request for a union was made by Christian Günther on October 18, and Finland's approval was received on October 25, but by November 5, the Soviet ambassador in Stockholm, Alexandra Kollontai, warned Sweden about the treaty. The Swedish government retreated from the issue but discussions for a more acceptable treaty continued until December when, on December 6, the Soviet Union and, on December 19, Germany announced their strong opposition to any kind of union between Sweden and Finland.

Road to War

At the autumn of 1940, Finnish generals visited Germany and occupied Europe several times to purchase additional material, guns and munition. Mannerheim even wrote a personal letter January 7, 1941 to Göring where he tried to persuade him to release Finnish purchased artillery pieces Germany had captured in Norwegian harbours during Weserübung. During one of these visits, Maj. Gen. Paavo Talvela met with Chief of Staff of OKH, Col. Gen Franz Halder and Göring January 15-18, 1941, and was asked about Finnish plans to defend itself in case of new Soviet invasion. The Germans also inquired about the possibility of someone from Finland coming and giving a presentation about the experiences of the Winter War.

After the resignation of president Kallio, Risto Ryti was elected by parliament as the new president of Finland December 19. Johan Wilhelm Rangell formed a new government January 4, and this time the fascist IKL party was included in the cabinet as an act of goodwill toward Nazi Germany.

Petsamo Crisis

The negotiations about Petsamo nickel mining rights had dragged on for six months when the Soviet Foreign Ministry announced January 14 that the negotiations had to be concluded quickly. The Soviet Union had demanded 75% ownership to the mine and to a nearby power plant together with the right to handle security in the area. On the same day, the Soviet Union interrupted grain deliveries to Finland. Soviet ambassador Zotov was recalled home January 18 and Soviet radio broadcasts started attacking Finland. January 21 Soviet Foreign Ministry issued an ultimatum demanding that nickel negotiations be concluded in two days.

When Finnish military intelligence spotted troop movements on the Soviet side of the border, Mannerheim proposed January 23 a partial mobilization, but Ryti and Rangell didn't accept. Ambassador Kivimäki reported January 24, that Germany was conscripting new age classes, and it was unlikely that they were needed against Britain.

Finnish Chief of Staff Lt.Gen. Heinrichs visited Berlin January 30-February 3, officially giving a lecture about Finnish experiences in the Winter War, but also including discussions with Halder. During the discussions Halder "speculated" about a possible German assault on the Soviet Union and Heinrichs informed him about Finnish mobilization limits and defence plans with and without German or Swedish participation.

Col. Buschenhagen had reported from northern Norway February 1 that the Soviet Union had collected 500 fishing ships in Murmansk, capable of transporting a division. Hitler ordered troops in Norway to occupy Petsamo (Operation Renntier) immediately if the Soviet Union started attacking Finland.

Mannerheim submitted his letter of resignation February 10 claiming that the continuing appeasement made it impossible to defend the country against an invader. He took his resignation back the next day after discussions with Ryti and after stricter instructions were sent to negotiators: 49% of mining rights to the Soviet Union, the power plant to a separate Finnish company, reservation of the highest management positions for Finns and no further Soviet agitation against Finland. Soviet Union rejected those terms on February 18, thus ending nickel negotiations.

Diplomatic Activities

After Heinrichs' visit and the end of the nickel negotiations, the diplomatic activities were halted for a few months. The most significant activities of that time was the visit of col. Buschenhagen in Helsinki and Northern Finland February 18-March 3 when he familiarized himself with the terrain and climate of Lappland. He also had discussions with Mannerheim, Heinrichs, Major General Airo and chief of operational office Colonel Tapola. Both parties were careful to point out the speculative nature of these discussions, although later these speculations became the basis of formal agreements.

Already in December 1940 leaders of Germany's Waffen-SS had demanded that Finland should "with deeds" show its orientation towards Germany. It was clear that it meant enlistment of Finnish troops to the SS. The official contact was made March 1, and in the following negotiations Finns tried in vain to transform the troops from SS to Wehrmacht in commemoration of the WWI-era Finnish Jäger Battalion. Ryti and Mannerheim considered the battalion necessary to reinforce German support of Finland, thence the nickname "Panttipataljoona" ("Pawn battalion"), and the negotiations were concluded at April 28 with the Finnish conditions that Government, Civil Guards or Armed Forces would not participate in enlistment and that all military personnel wishing to parcipate must first take their leave of the Finnish army. These conditions were designed to limit Finnish commitment to Nazi Germany. The enlistment was carried out in May and in June they were transferred to Germany where a Finnish SS battalion was founded June 18. Foreign minister Witting informed Sweden, where similar activities were also conducted, already on March 23 about possible enlistment. The British ambassador to Helsinki, Gordon Vereker, notified the Finnish Foreign Ministry May 16 on the issue, demanding the end of enlistment.

Relations between Sweden and Germany strained in March, and Sweden mobilized March 15 80,000 more men and moved military units to the southern coast and western border making it even more likely that Sweden couldn't support Finland if war broke out. This also affected Swedish-Finnish co-operation as the Finnish interest for intelligence exchange diminished considerably during April.

Race issues were sources of particular concern: the Finns were not viewed favourably by the Nazi race theorists. By active participation on Germany's side, Finnish leaders hoped for a more independent position in post-war Europe, through the removal of the Soviet threat and the incorporation of the related Finnic peoples of neighbouring Soviet areas, especially Karelia. This view gained increasing popularity in the Finnish leadership, and also in the press, during the spring of 1941.

From February to April Germany prepared Barbarossa in secret, and apart from the above contacts no operational or political discussions were concluded during this time. Instead they published disinformation, such as claims that the German troop buildup in the East was merely a ruse ahead of a planned invasion of Britain (such a plan had been considered under the codename Operation Seawolf) or safe training locations from British bombers, to hide their real intentions. When Germany invaded Yugoslavia and Greece beginning on April 6, suspicion of German intentions increased in Finland, though uncertainty still prevailed as to whether Hitler really intended to attack the Soviet Union before the Battle of Britain was concluded.

However, the Finns had in the past bitterly learned how a small country can be used as small change in the deals of great powers, and in such a case Finland could have been used as a token of reconciliation between Hitler and Stalin, something which the Finns had every reason to fear, which is why the relations with Berlin were considered of the utmost priority for the future of Finland, especially so if the war between Germany and Soviet Union failed to materialize.

Once again the German Foreign Ministry sent Ludwig Weissauer to Finland May 5, this time to clarify that war between Germany and the Soviet Union would not be launched before spring 1942. Ryti and Witting believed that at least officially, and forwarded the message to Swedish Foreign Minister Günther, who was visiting Finland May 6-May 9. Witting also sent the information to Finnish ambassador to London Gripenberg. When the war broke out only a couple of weeks later, it was understandable that both the Swedish and British governments felt that the Finns had lied to them.

Part of that disinformation campaign was a request to ambassador Kivimäki that Finland should offer proposals for a new borderline Germans could pressure the Soviets to accept in negotiations. On May 30, 1941 General Airo produced five alternate border drafts for delivery to the Germans, who should then propose the best they felt they could bargain from the Soviet Union. In reality, the Germans had no such intentions, but the exercise served to fuel the support among leading Finns for taking part in Operation Barbarossa.

Operations like Barbarossa don't begin without some advance notice, and the worsening of Soviet-German relations which began with the meeting in Berlin November 12 was seen around from the end of March 1941. Stalin tried to improve relations toward the Third Reich by taking the leadership of the Soviet government May 6 and backed off from unimportant issues and fulfilled all trade deals even as German deliveries were late. Part of that policy was also improving relations with Finland. A new ambassador, Pavel Orlov, was named to Helsinki April 23 and a gift of a trainload of wheat was presented to J. K. Paasikivi when he retired from Moscow. The Soviet Union also renounced opposition to a Swedish-Finnish defence alliance, but Swedish disinterest and German opposition to that kind of alliance rendered that change moot. Also Soviet radio propaganda against Finland ceased. Orlov acted very conciliatory and soothed many feelings which had been raised by his predecessor, but as he failed to solve any critical issues like the disagreement over petsamo nickel or to restart grain imports from Soviet Union, his line was seen only as a new facade to old policy.

British ambassador Vereker saw Finland moving towards Germany, and due to his reports British Foreign office had requested easing Finnish trade regulations in Petsamo March 30. At April 28 Vereker reported that the British government should pressure the Soviet Union to return Hanko or Vyborg to Finland as he saw it as the only possible way to secure Finnish neutrality in the case of German-Soviet war.

The Petsamo crisis had disillusioned Finnish politicians, especially Ryti and Mannerheim, creating the impression that peaceful co-existence with the Soviet Union was impossible, and that Finland would survive in peace only if the Soviet Union was defeated, as Ryti presented it to US ambassador Arthur Schoenfeld on April 28. The effect of this general feeling was that voices advocating closer ties with Germany grew stronger and the voices advocating armed neutrality within Finland's new borders (some among the Social Democrats, and some of the more left-leaning in the Swedish People's Party) softened. Contacts with Sweden's Conservative Foreign Minister Günther showed an enthusiasm unusual for the Swedes for the anticipated "Crusade against Bolshevism".

After the successful occupation of Yugoslavia and Greece by the spring of 1941, the German army's standing was at its zenith, and its victory in the war seemed more than likely. The envoy of the German Foreign Ministry, Karl Schnurre, visited Finland May 20-24, and invited one or more staff officers to negotiations in Salzburg.

Cooperation with Germany

A group of staff officers led by gen. Heinrichs left Finland on May 24 and participated in discussions with OKW in Salzburg on May 25 where the Germans informed them about the northern part of Operation Barbarossa. The Germans also presented their interest in using Finnish territory to attack from Petsamo to Murmansk and from Salla to Kandalaksha. Heinrichs presented Finnish interest in Eastern Karelia, but Germany recommended a passive stance. The negotiations continued the next day in Berlin with OKH, and contrary to the negotiations of the previous day, Germany wanted Finland to form a strong attack formation ready to strike on the eastern or western side of Lake Ladoga. The Finns promised to examine the proposal, but notified the Germans that they were only able to arrange supply to the Olonets-Petrozavodsk-line. The issue of mobilization was also discussed. It was decided that the Germans would send signal officers to enable confidential messaging to Mannerheim's headquarters in Mikkeli. Naval issues were discussed, mainly for securing sea lines over the Baltic Sea, but also possible usage of the Finnish navy in the upcoming war. During these negotiations the Finns presented a number of material requests ranging from grain and fuel to airplanes and radio equipment.

Heinrichs' group returned on May 28 and reported their discussions to Mannerheim, Walden and Ryti. And on May 30 Ryti, Witting, Walden, Kivimäki, Mannerheim, Heinrichs, Talvela and Aaro Pakaslahti from Foreign Ministry had a meeting where they accepted the results of those negotiations with a list of some prerequisites: a guarantee of Finnish independence, the pre-Winter War borders (or better), continuing grain deliveries, and that Finnish troops would not cross the border before a Soviet incursion.

The next round of negotiations occurred in Helsinki on June 3-June 6 regarding some practical details. During these negotiations it was decided that Germany would be responsible for the area north of Oulu. This area was easily given to them because it was sparsely inhabited and non-critical to the defence of the more important southern provinces. The Finns also agreed to give two divisions to the Germans in northern Finland (30 000 men) and to the usage of airfields in Helsinki and Kemijärvi (Because of the number of German aircraft, airfields at Kemi and Rovaniemi were added later). Finland also warned Germany that an attempt to establish a Quisling government would cut co-operation and that they considered it very important that Finland not be the aggressor and that no invasion should be launched from Finnish soil.

The negotiations for naval operations continued on June 6 in Kiel. It was agreed that the Kriegsmarine would close the Gulf of Finland with mines as soon as the war began.

The arrival of German troops participating in Operation Barbarossa began on June 7 in Petsamo, where SS Division Nord started southwards, and on June 8 in the ports of the Gulf of Bothnia where the German 169th Infantry Division was transported by rail to Rovaniemi, where both of these turned eastward on June 18. Britain cancelled all naval traffic to Petsamo June 14 in protest of these moves. Starting from June 14 a number of German minelayers and supporting MTBs arrived in Finland, some on an official naval visit, others hiding in the southern archipelago.

Finnish parliament was informed for the first time on June 9, when first mobilization orders were issued for troops needed to safeguard the following mobilization phases, like anti-air and border guard units. The Committee on Foreign Affairs complained that parliament was bypassed when deciding on these issues, and protesting that Parliament should be trusted with sensitive information, but no other actions were taken. Swedish ambassador Karl-Ivan Westman wrote that the Soviet-minded "Sextuples", the far-left Social Democrats, were the reason that parliament couldn't be trusted in foreign policy questions. When Soviet news agency TASS reported on June 13 that no negotiations were ongoing between Germany and the Soviet Union, Ryti and Mannerheim decided to delay mobilization as no guarantees had been received from Germany. General Waldemar Erfurt, who has been nominated as liaison officer to Finland on June 11, reported to OKW June 14, that Finland wouldn't finalize mobilization unless the prerequisites were granted. Although the Finns continued on the same day (June 14) with the second phase of mobilization, this time the mobilizing forces were located in northern Finland and later operated under German command. Field Marshall Keitel send a message on June 15 stating that the Finnish prerequisites were accepted, and the general mobilization started on June 17, two days later than scheduled.

An airfield in Utti was evacuated by Finnish planes on June 18 and the Germans were allowed to use it for refueling from June 19. German reconnaissance planes were stationed at Tikkakoski, near Jyväskylä, on June 20.

On June 20 Finland's government ordered 45,000 people at the Soviet border to be evacuated. On June 21 Finland's chief of the General Staff, Erik Heinrichs, was finally informed by his German counterpart that the attack was to begin.

To the Opening of Hostilities

Operation Barbarossa had already commenced in the northern Baltic by the late hours of June 21, when German minelayers, which had been hiding in the Finnish archipelago, laid down two large minefields across the Gulf of Finland, one at the mouth of the gulf and a second in the middle of the Gulf.

These minefields ultimately proved sufficient to confine the Soviets' Baltic fleet to the easternmost part of the Gulf of Finland until the end of the Continuation War. Three Finnish submarines participated in the mining operation by laying 9 small fields between Suursaari Island and the Estonian coast.

Later the same night German bombers, flying from East Prussian airfields, flew along the Gulf of Finland to Leningrad and mined the harbour and the river Neva. Finnish air defence noticed that one group of these bombers, most likely the ones responsible for mining the river Neva, flew over southern Finland. On the return trip, these bombers refuelled in Utti airfield before returning to East Prussia.

Finland feared that the Soviet Union would occupy Åland as soon as possible and use it to close naval routes from Finland to Sweden and Germany (together with Hanko base), so Operation Kilpapurjehdus (Sail Race) was launched in the early hours of June 22 to occupy Åland. Soviet bombers launched attacks against Finnish ships during the operation but no damage was inflicted.

Individual Soviet artillery batteries started to shoot at Finnish positions from Hanko early in the morning, so the Finnish commander sought permission to return fire, but before the permission was granted, the Soviet artillery had stopped shooting.

On the morning of June 22, the German Gebirgskorps Norwegen started Operation Renntier and began its move from Northern Norway to Petsamo. The German ambassador initiated urgent negotiations with Sweden for transfer of the German 163rd Infantry Division from Norway to Finland using Swedish rail. Sweden agreed to this on June 24.

On the morning of June 22, both the Soviet Union and Finland declared that each would be neutral in respect of the other in the war that was now underway. This precipitated unease in the Nazi leadership, which tried to provoke a response from the Soviet Union by using both the Finnish archipelago as a base, and Finnish airfields for refueling. Hitler's public statement worked in the same direction; Hitler declared that Germany would attack the Bolshevists "(...) in the North in alliance ["im Bunde"] with the Finnish freedom heroes". This was in flat contradiction of the statement made to parliament by British Foreign Secretary Eden on June 24 affirming Finnish neutrality.

Finland did not allow direct German attacks from its soil to the Soviet Union, so German forces in Petsamo and Salla had to hold their fire. Air attacks were also prohibited, and very bad weather in northern Finland helped to keep the Germans from flying. Only one attack from Southern Finland against the White Sea Canal was approved, but even that had to be cancelled due to bad weather. There were occasional individual and group level small arms shooting between Soviet and Finnish border guards, but otherwise the front was quiet.

To keep a close eye on their opponents, both parties -and also the Germans- performed active air reconnaissances over the border, but no air fights ensued.

After three days, early on the morning of June 25, the Soviet Union made its move and unleashed a major air offensive against 18 cities with 460 planes, mainly striking airfields but seriously damaging civilian targets as well. The worst damage was done in Turku, where the airfield become inoperable for a week, but among civilian targets, the Medieval Turku Castle was also destroyed. (After the war the castle was repaired, but the work took three decades and was not completed until 1977.) Heavy damage to civilian targets was also sustained in Kotka and Heinola. However, civilian casualties of this attack were relatively limited.

The Soviet Union justified the attack as being directed against German targets in Finland, but even the British embassy had to admit that the heaviest hits had been taken by southern Finland, and airfields where there were no Germans. Only two targets had German forces present at the time of attack: Rovaniemi and Petsamo. Once again Foreign Minister Eden had to admit to parliament on June 26 that the Soviet Union had initiated the war.

A meeting of parliament was scheduled for June 25 when Prime Minister Rangell had been due to present a notice about Finland's neutrality in the Soviet-German war, but the Soviet bombings led him to instead observe that Finland was once again at war with the Soviet Union. The Continuation War had begun.

Conclusion

What began for the Finns as a defensive strategy, designed to provide a German counterweight to Soviet pressure, ended as an offensive strategy, aimed at re-conquest of the formerly Finnish Karelia and an invasion of East Karelia in the Soviet Union. The Finns had been lured by the prospects of regaining their lost territories and ridding themselves of the Soviet threat into becoming a party to Nazi Germany's planned invasion of the USSR.

Finnish Offensive 1941

Finnish_advance_in_Karelia_during_the_Continuation_War.png

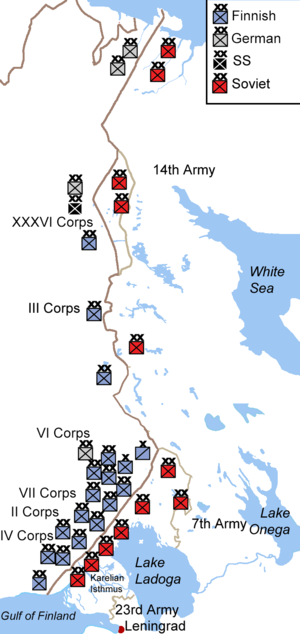

Mobilized units started moving towards the border on June 21, and they were arranged into defensive formations as soon as they arrived at the border. Finland was able to mobilize 16 infantry divisions, one cavalry brigade, and two "Jäger" brigades, which were practically normal infantry brigades, except for one battalion in the 1st Jaeger Brigade (1.JPr), which was armored using captured Soviet equipment. There were also a handful of separate battalions, mainly formed from Border Guard units and used mainly for reconnaissance. Soviet military plans has estimated that the Finns would be able to mobilize only 10 infantry divisions, as they had done in the Winter War, but they failed to take into account materiel the Finns had purchased between the wars and the training of all available men. In northern Finland there were also two German Mountain Divisions at Petsamo and two German Infantry divisions at Salla. Another German infantry division was en route through Sweden to Ladoga Karelia, although one reinforced regiment was later redirected from it to Salla.

When the war started, the Soviet Union had 23rd Army in Karelian Isthmus consisting of 50th and 19th Corps and 10th Mechanized Corps, together 5 Infantry, 1 Motorized and 2 Armored divisions. At Ladoga Karelia there was 7th Army consisting of 4 Infantry divisions. In Murmansk-Salla region the Soviet Union had 14th Army with 42nd Corps, consisting of 5 Infantry divisions (1 as reserve in Archangelsk) and 1 Armored division. Also the Soviets had around 40 battalions, separate regiments and fortification units which were not part of their divisional structure. In Leningrad there were 3 Infantry divisions and one Mechanized Corps.

The initial German strike against the Soviet Air Force had not touched air units located near Finland, so the Soviets could field nearly 750 Air Force planes and part of the 700 planes the Soviet Navy had against 300 Finnish planes.

The Soviet war against Germany did not go as well as pre-war Soviet wargames had envisioned, and soon Soviet high command had to take units from wherever they could, so although Soviets had started the war against Finland, they could not follow the initial air offensive with a supporting land offensive. They also had to withdraw the 10th Mechanized Corps with two armored divisions and 237th Infantry division from Ladoga Karelia thus stripping reserves from defending units.

Reconquest of Ladoga Karelia

Initially the Finnish army was deployed in a defensive formation, but on June 29 Mannerheim created the Army of Karelia, commanded by Lt. Gen. Heinrichs, and ordered it to prepare to attack Ladoga Karelia. The Army of Karelia consisted of VI Corps (5th and 11th Divisions), VII Corps (7th and 9th divisions) and Group O (Cavalry Brigade, 1st Jaeger Brigade and 2nd Jaeger Brigade). Also later when 1. division and two regiments of German 163. division arrived to the area they were given to the Army of Karelia.

Opposing them were the Soviet 7th Army with 168th Division near Sortavala and 71st Division north of Jänisjärvi ("Hare Lake"). Soviets had prepared field fortifications along the border across Sortavala and to the important road crossings at Värtsilä and Korpiselkä.

On July 9, the order for offensive was given. The duty to break through the Soviet defences was given to VI Corps, commanded by hero of Battle of Tolvajärvi, Maj. Gen. Paavo Talvela. He had borrowed as much artillery as possible from other units of the Army of Karelia and even 1st Jaeger Brigade. (Col. Ruben Lagus) from Group O. With strong artillery support he unleashed 5th Division (Col. Koskimies) to Korpiselkä July 10 and the defenders were overwhelmed by next morning. Talvela wasn't satisfied with aggressiveness of Koskimies, and he relieved him from the command and gave 5th Division to Col. Lagus.

Lagus pursued retreating Soviet IR 52 eastward with his light units and reached Tolvajärvi July 12. Then he turned southwards and advanced using small roads, some in such worse shape that men had to carry their bicycles. On July 14 his forces cut Sortavala-Petrozavodsk railroad, and next day they reached shores of Lake Ladoga, cutting Soviet routes around the lake. Soviets had to transfer two regiments and separate battalions from Karelian Isthmus to close down the hole on the eastern side of Lake Ladoga.

The 11th division (Col. Heiskanen) had already July 4 found that Soviet forces had temporarily abandoned their trenches across the border, and they used the opportunity to capture them. When the general offensive began, they had already pushed July 9 eastward from their captured positions over the roadless terrain and cut the road running from Korpiselkä to Värtsilä and Suistamo, on the eastern shore of Jänisjärvi. From there they threatened to encircle Soviet forces south of Korpiselkä and those fortified in Värtsilä, so to prevent encirclement, they had to leave their positions and retreat eastward. Soviet IR 367 was able to hold its positions north of Jänisjärvi until defenders of Värtsilä had retreated there July 12. Heiskanen continued pressing Soviet IR 367 around the eastern side of Jänistärvi, and reached Jänisjoki, running from Jänisjärvi to Lake Ladoga July 16, where they set on defensive.

Lagus continued his offensive immediately along the north-eastern coast of Lake Ladoga. Soviet Mot. IR 452 was coming from Karelian Isthmus and its first parts set to defensive at Salmi, where Tulemajoki reaches Lake Ladoga. Finns arrived there on July 18, and early next morning Finns started the battle by crossing the river 5km north of Salmi and managed to cut the roads leading to Salmi by afternoon. Next day Finns were able to push into the village and only small units were able to escape the encirclement. Salmi was finally captured by early hours of July 21.

Reconquest of Karelian Isthmus

Occupation of East Karelia

Advancement from Northern Finland

Political Development

On July 10, the Finnish army began a major offensive on the Karelian Isthmus and north of Lake Ladoga. Mannerheim's order of the day, the Sword scabbard declaration, clearly states that the Finnish involvement was an offensive one.[3] (http://www.mannerheim.fi/10_ylip/e_mtuppi.htm) By the end of August 1941, Finnish troops had reached the pre-war boundaries. The crossing of the pre-war borders led to tensions in the army, the cabinet, the parties of the parliament, and domestic opinion. Military expansionism might have gained popularity, but it was far from unanimously championed.

Also, international relations were strained — notably with Britain and Sweden, whose governments in May and June had learned in confidence from Foreign Minister Witting that Finland had absolutely no plans for a military campaign coordinated with the Germans. Finland's preparations were said to be purely defensive.

Sweden's leading cabinet members had hoped to improve the relations with Nazi Germany through indirect support of Operation Barbarossa, mainly channelled through Finland. Prime Minister Hansson and Foreign Minister Günther found however, that the political support in the National Unity Government and within the Social Democratic organizations turned out to be insufficient, particularly after Mannerheim's Sword Scabbard Declaration, and even more so after Finland within less than two months undeniably had begun a war of conquest. A tangible effect was that Finland became still more dependent on food and munitions from Germany.

The Commonwealth put Finland under blockade and the British ambassador was withdrawn. On July 31, 1941, British RAF made an air raid on the northern Finnish port of Petsamo [4] (http://www.fleetairarmarchive.net/RollofHonour/Battlehonour_crewlists/Petsamo_Kirkenes_1941.html). Damages were limited since the harbour was almost empty of ships.

September 11, the U.S. ambassador Arthur Schoenfeld was informed that the offensive on the Karelian Isthmus was halted on the pre-Winter War border (with a few straightened curves at the municipalities of Valkeasaari and Kirjasalo), and that "under no conditions" Finland would participate in an offensive against Leningrad, but would instead maintain static defence and wait for a political resolution. Witting stressed to Schoenfeld that Germany, however, should not hear of this.

On September 22, a British note was presented (by Norway's ambassador Michelet) demanding the expulsion of German troops from Finland's territory and Finland's withdrawal from East Karelia to positions behind the pre-Winter War borders. Finland was threatened by a British declaration of war unless the demands were met. The declaration of war was exacted on Finland's Independence Day, December 6.

In December 1941, the Finnish advance had reached River Svir (which connects the southern ends of Lake Ladoga and Lake Onega and marks the southern border of East Karelia). By the end of 1941, the front stabilized, and the Finns did not conduct major offensive operations for the following two and a half years. The fighting morale of the troops declined when it was realized that the war would not soon end.

It has been suggested that the execution of the prominent pacifist leader Arndt Pekurinen in November 1941 was due to fear of army demoralization being exacerbated by such activism.

International volunteers and support

Like in the Winter War, Swedish volunteers were recruited. Until December, for guarding the Soviet naval base at Hanko, that was then evacuated by sea, and the Swedish unit was officially disbanded. During the Continuation War, the volunteers signed for three–six months of service. In all, over 1,600 fought for Finland, though only about 60 remained by the summer of 1944. About a third of the volunteers had been engaged already in the Winter War. Another significant group, about a fourth of the men, were Swedish officers on leave.

There was also a SS-battalion of volunteers on the northern Finnish front 1942–1944, that was recruited from Norway, then under German occupation, and similarly some Danes.

About 3,400 Estonian volunteers also took part of the Continuation War.

Diplomatic manoeuvres

Operation Barbarossa was planned as a blitzkrieg lasting a few weeks. British and US observers believed that the invasion would be concluded before August. In the autumn of 1941, this turned out to be wrong, and leading Finnish military officers started to mistrust Germany's capacity. German troops in Northern Finland faced circumstances they were not properly prepared for, and failed badly to reach their targets, most importantly Murmansk. Finland's strategy now changed. A separate peace with the Soviet Union was offered, but Germany's strength was too great. The idea that Finland had to continue the war while putting its own forces at the least possible danger gained increasing support, perhaps in the hopes that the Wehrmacht and the Red Army would wear each other down enough for negotiations to begin, or to at least get them out of the way of Finland's independent decisions. Some may also have still hoped for an eventual victory by Germany.

Finland's participation in the war brought major benefits to Nazi Germany. The Soviet fleet was blockaded in the Gulf of Finland, so that the Baltic was freed for the training of German submarine crews as well as for German shipping, especially for the transport of the vital iron ore from northern Sweden, and nickel and rare metals needed in steel processing from the Petsamo area. The Finnish front secured the northern flank of the German Army Group North in the Baltic states. The sixteen Finnish divisions tied down numerous Soviet troops, put pressure on Leningrad — although Mannerheim refused to attack — and threatened the Murmansk Railroad. Additionally, Sweden was further isolated and was increasingly pressured to comply with German and Finnish wishes, though with limited success.

Despite Finland's contributions to the German cause, the Western Allies had ambivalent feelings, torn between residual goodwill for Finland and the need to accommodate their vital ally, the Soviet Union. As a result, Britain declared war against Finland, but the United States did not. There was no combat between these countries and Finland, but Finnish sailors were interned overseas. In the United States, Finland was highly regarded, partly due to having continued to make payments on its World War I debt faithfully throughout the inter-war period.

The Allies often characterize Finland as one of the Axis Powers, although the term used in Finland is "co-belligerence with Germany". Finland later also earned respect in the West for the strength of its democracy and its refusal to allow extension of Nazi anti-Semitic practices in Finland. Finnish Jews served in the Finnish army, and Jews were not only tolerated in Finland[5] (http://www.finemb.org.il/Historia.htm), but most Jewish refugees were granted asylum (only 8 of the more than 500 refugees were handed over to the Nazis, and these 8 were expelled only because they had a criminal record in Finland, not because of German requests). The field synagogue in Eastern Karelia was probably unique on the Axis side during the war. However, in the few cases Jewish officers from Finland's defence forces were awarded the German Iron Cross, they declined.

About 2,600–2,800 Soviet prisoners of war were handed over to the Germans. Most of them (around 2,000) joined the Russian Liberation Army. The rest were mainly army officers and political officers (and a handful of Jewish refugees), most of them dying in Nazi concentration camps, while some were given to the Gestapo for interrogation. Sometimes these handovers were demanded in return of arms or food, and sometimes the Finns received Soviet prisoners of war in return. These were mainly Estonians and Karelians willing to join the Finnish army. These, as well as some volunteers from the occupied Eastern Karelia, formed the Tribe Battalion (Finnish: "Heimopataljoona"). At the end of the war, the USSR required that the members of the Tribe Battalion were to be handed over to the Soviet Union. Some managed to escape before or during the transport, but most of them were either sent to the Gulag camps or executed.

In 1941, even before the Continuation War, one battalion of Finnish volunteers joined the German Waffen-SS with silent approval of the Finnish government. It has been concluded that the battalion served as a token of Finnish commitment to cooperation with Nazi Germany. This battalion, named the Finnisches Freiwilligen Bataillon fought as part of SS Division Wiking in the Ukraine and Caucasus. The battalion was pulled back from the front in May 1943 and was transported to Tallinn where it was disbanded on July 11. The soldiers were then transferred into different units of the Finnish army.

The end of the war

Finland began to actively seek a way out of the war after the disastrous German defeat at Stalingrad in January–February 1943. Edwin Linkomies formed a new cabinet with the peace process as the top priority. Negotiations were conducted intermittently in 1943–44 between Finland and its representative Juho Kusti Paasikivi on the one side, and the Western Allies and the Soviet Union on the other, but no agreement was reached.

Instead, on June 9, 1944, the Soviet Union opened a major offensive against Finnish positions on the Karelian Isthmus and in the Lake Ladoga area (it was timed to accompany D-Day). On the second day of the offensive, the Soviet forces broke through the Finnish lines, and in the succeeding days they made advances that appeared to threaten the survival of Finland. Finland especially lacked modern anti-tank weaponry, which could stop heavy Soviet tanks, and German Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop offered them in exchange for a guarantee that Finland would not again seek a separate peace. On June 26 President Risto Ryti gave this guarantee as a personal undertaking, which he intended to last for the remainder of his presidency. In addition to material deliveries, Hitler sent some assault gun brigades and a Luftwaffe fighter-bomber unit to temporarily support the most threatened defence sectors.

With new supplies from Germany, the Finns were now equal to the crisis, and halted the Russians in early July 1944, after a retreat of about one hundred kilometres that brought them to approximately the same line of defence they had held at the end of Winter War, the VKT-line (for "Viipuri–Kuparsaari–Taipale" running from Vyborg to River Vuoksi, and along the river to Lake Ladoga at Taipale), where the Soviet offensive was stopped in the Battle of Tali-Ihantala, in spite of nearly a third of their military machine being concentrated against the Finns. Finland had already become a sideshow for the Soviet leadership, who now turned their attention to Poland and southeastern Europe. The United States had already succeeded in their landing in France and were pushing towards Germany, and the Soviet leadership did not want to give them a free hand in Central Europe. Although the Finnish front was once again stabilized, the Finns were exhausted and wanted to get out of the war.

Mannerheim had repeatedly reminded the Germans that in case their troops in Estonia retreated, Finland would be forced to make peace even at very unfavourable terms. Soviet-occupied Estonia would have provided the enemy a favourable base for amphibious invasions and air attacks against Helsinki and other cities, and would have strangled Finnish access to the sea. When the Germans indeed withdrew, the Finnish desire to end the war increased. Perhaps realizing the validity of this point, initial German reaction to Finland's announcement of ambitions for a separate peace was limited to only verbal opposition.

President Ryti resigned, and Finland's military leader and national hero, Carl Gustaf Mannerheim, was extraordinarily appointed president by the parliament, accepting responsibility for ending the war.

On September 4 the cease-fire ended military actions on the Finnish side. The Soviet Union ended hostilities exactly 24 hours after the Finns. An armistice was signed in Moscow on September 19 between the Soviet Union and Finland. Finland had to make many limiting concessions: the Soviet Union regained the borders of 1940, with the addition of the Petsamo area; the Porkkala Peninsula (adjacent to Finland's capital Helsinki) was leased to the USSR as a naval base for fifty years (but returned in 1956), and transit rights were granted; Finland's army was to demobilize in haste, and Finland was required to expel all German troops from its territory. As the Germans refused to leave Finland voluntarily, the Finns had no choice but to fight their former supporters in the Lapland War.

Conclusion

In retrospect the Continuation War could be seen as the result of a series of political miscalculations by the Finnish leadership in which Finland's martial abilities clearly outshone her diplomatic skills. However, the matter has been thoroughly scrutinized in Finland, and many commentators also hold that Finland was a victim of bad luck in addition to any failings on its own part, being forced to make a choice in a situation when any of the available alternatives would result in being attacked by either side. Not joining the war with Germany against Soviet Union would almost certainly have lead to occupation attempts by either side of that great conflict, and thus Finland's involvement anyway.

According to the prior proceedings of war at the time, Finland chose the alternative that seemed then to provide better chances of post-war survival. After the fall of the Soviet Union, it's become clear that Finland maybe more by luck than by skill happened to make the right choice after the Winter War by fervently seeking to reverse the German disinterest. A Soviet occupation, and a fate surely worse than that of the other Border States, would otherways have been unavoidable.

The aged Field Marshal Mannerheim might have been responsible for a couple of misjudgements, for instance the infamous Sword scabbard declaration in the Order of the Day of July 10, 1941, but at the end of the war he had earned a remarkable reputation among former foes and allies, in Finland as well as abroad, which to a considerable degree eased Finland's extrication from a potentially disastrous undertaking.

In any event, Finland's fate was no worse than any other country struck by the World War — quite the contrary. Finland had defended her territory and her civilians with more success than most other European countries. Only 2,000 Finnish civilians were killed during World War II, and only relatively narrow border regions had been conquered by force. For nearly three years until June 20, 1944, when Vyborg fell, not one major Finnish town was besieged or occupied. During the war there were three capital cities of belligerent European countries that were not occupied by force at some stage: London, Moscow and Helsinki.

After the war, Finland preserved her independence while adjusting her foreign policy to avoid offence to the USSR, now the world's second superpower, a concession which the Soviet government reciprocated by surrendering part of its gains from the postwar settlement and refraining from too obvious intrusions in Finland's domestic affairs. To Moscow, an independent Finland seemingly was a price worth paying for keeping Sweden formally neutral in the Cold War, a quid pro quo that for forty years safeguarded wider Soviet strategic interests in the region.

Battles and operations

See also

- British military history

- Co-belligerence

- Finlandization

- History of Finland

- History of Russia

- List of Finnish corps in the Continuation War

- List of Finnish divisions in the Continuation War

- List of Finnish wars

- Lotta Svärd

- Paasikivi doctrine

- Paasikivi-Kekkonen Line

- Salpalinja

- Volkhov Front

| Campaigns and theatres of World War II |

| European Theatre |

| Poland | Phony War | Denmark & Norway | France & Benelux countries | Britain |

| Eastern Front 1941-45 | Western Front 1944-45 |

| Asian and Pacific Theatres |

| China | Pacific Ocean | South-East Asia | South West Pacific | Manchuria 1945 |

| The Mediterranean, Africa and Middle East |

| Mediterranean Sea | East Africa | North Africa | West Africa | Balkans Middle East | Madagascar | Italy |

| Other |

| Atlantic Ocean | Strategic bombing | Raiding operations |

| Contemporaneous wars |

| Chinese Civil War | Winter War | Continuation War |

de:Fortsetzungskrieg fi:Jatkosota ja:継続戦争 sv:Finska fortsättningskriget ru:Война-продолжение