Congress of the United States

|

|

The Congress of the United States is the legislative branch of the federal government of the United States of America. It is established by Article One of the Constitution of the United States, which also delineates its structure and powers. Congress is a bicameral legislature, consisting of the House of Representatives (the "Lower House") and the Senate (the "Upper House").

The House of Representatives consists of 435 members, each of whom is elected by a congressional district and serves a two-year term. Seats in the House are divided between the states on the basis of population, with each state entitled to at least one seat. In the Senate, on the other hand, each state is represented by two members, regardless of population. As there are fifty states in the Union, the Senate consists of 100 members. Each Senator, who is elected by the whole state rather than by a district, serves a six-year term. Senatorial terms are staggered so that approximately one-third of the terms expire every two years.

The Constitution vests in Congress all the legislative powers of the federal government. The Congress, however, only possesses those powers enumerated in the Constitution; other powers are reserved to the states, except where the Constitution provides otherwise. Important powers of Congress include the authority to regulate interstate and foreign commerce, to levy taxes, to establish courts inferior to the Supreme Court, to maintain armed forces, and to declare war. Insofar as passing legislation is concerned, the Senate is fully equal to the House of Representatives. The Senate is not a mere "chamber of review," as is the case with the upper houses of the bicameral legislatures of most other nations.

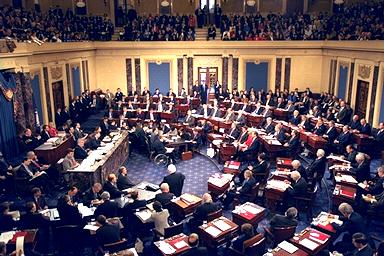

Both Houses of Congress meet in the Capitol in Washington, D.C.

| Contents |

Composition

The Senate currently has 100 seats, one-third being renewed every two years; two members are elected from each U.S. state by popular vote to serve six-year terms. Each state has equal representation in the Senate because at the Constitutional Convention, where every state had one vote, the small states refused to go along with any Constitution that did not give them an equal vote in at least one house of Congress. Because terms are staggered, every state will have a junior and senior Senator.

The House of Representatives currently has 435 seats for voting Members. Additionally, there are non-voting delegates from the District of Columbia, American Samoa, Guam, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands. Members are directly elected by first past the post to serve two-year terms from Congressional districts. Only the non-voting delegate from Puerto Rico (known as Resident Commissioner) is elected to a four-year term. The states with the very small populations—smaller than the population of a whole Congressional district elsewhere—are still guaranteed one whole seat. These seats are apportioned according to the population of each state, but the total number is fixed by statute at 435 (Public Law 62-5).

The U.S. Congress has fewer women in it than legislatures in other countries, as well as many more lawyers. The percentage of lawyers in Congress fluctuates around 45 percent. In contrast, in the Canadian House of Commons, the British House of Commons, and the German Bundestag, approximately 15 percent of members have law degrees.

History

During the American Revolutionary War and under the Articles of Confederation, the Congress of the United States was named the Continental Congress.

The first Congress under the current Constitution started its term in Federal Hall in New York City on March 4, 1789 and their first action was to declare that the new Constitution of the United States was in effect. The United States Capitol building in Washington, D.C. hosted its first session of Congress on November 17, 1800.

Proceedings of the United States Congress were televised for the first time on January 3, 1947. Proceedings of the general Congress are now regularly broadcast on C-SPAN, as are newsworthy meetings of committees and subcommittees. Details of the activities of Congress can also be found on the internet, on the legislative database THOMAS.

Specific powers held by the Congress

The powers of the Congress are set forth in Article 1 (particularly Article 1, Section 8) of the United States Constitution. The powers originally delegated to the Congress by the original version of the Constitution were supplemented by the post-Civil War amendments to the Constitution (Amendments 13, 14, and 15, each of which authorizes the Congress to enforce its provisions by appropriate legislation), and by the 16th Amendment, which authorizes an income tax.

Other parts of the Constitution—particularly Article 1, Section 9, and the first ten amendments to the Constitution (popularly known as the Bill of Rights)—impose limitations on Congress's power.

Each house of Congress has the power to introduce legislation on any subject dealing with the powers of Congress, except for legislation dealing with gathering revenue (generally through taxes), which must originate in the House of Representatives (specifically the U.S. House Committee on Ways and Means). The large states may thus appear to have more influence over the public purse than the small states. In practice, however, each house can vote against legislation passed by the other house. The Senate may disapprove a House revenue bill—or any bill, for that matter—or add amendments that change its nature. In that event, a conference committee made up of members from both houses must work out a compromise acceptable to both sides before the bill becomes the law of the land.

The broad powers of the whole Congress are spelled out in Article I of the Constitution:

- To levy and collect taxes

- To borrow money for the public treasury

- To make rules and regulations governing commerce among the states and with foreign countries

- To make uniform rules for the naturalization of foreign citizens

- To coin money, state its value, and provide for the punishment of counterfeiters

- To set the standards for weights and measures

- To establish bankruptcy laws for the country as a whole

- To establish post offices and post roads

- To issue patents and copyrights

- To punish piracy

- To declare war

- To raise and support armies

- To provide for a navy

- To call out the militia to enforce federal laws, suppress lawlessness, or repel invasions

- To make all laws for the seat of government (Washington, D.C.)

- To make all laws necessary to enforce the Constitution

Some powers are added in other parts of the Constitution:

- To set up a system of federal courts (set out in Article III)

- To prohibit slavery (set out in the Thirteenth Amendment)

- To enforce the right of citizens to vote, irrespective of race (set out in the Fifteenth Amendment)

The Tenth Amendment sets definite limits on congressional authority, by providing that powers not delegated to the national government are reserved to the states or to the people.

In addition, the Constitution specifically forbids certain acts by Congress. It may not:

- Suspend the writ of habeas corpus—a requirement that those accused of crimes be brought before a judge or court before being imprisoned —unless necessary in time of rebellion or invasion

- Pass laws that condemn persons for crimes or unlawful acts without a trial (attainder)

- Pass any law that retroactively makes a specific act a crime (ex post facto)

- Levy direct taxes on citizens, except on the basis of a census already taken (This was overridden by the Sixteenth Amendment)

- Tax exports from any one state

- Give specially favorable treatment in commerce or taxation to the seaports of any state or to the vessels using them

- Authorize any titles of nobility

The Congress also has sole jurisdiction over impeachment of federal officials. The House has the sole right to bring the charges of misconduct which would be considered at an impeachment trial, and the Senate has the sole power to try impeachment cases and to find officials guilty or not guilty. A guilty verdict requires a two-thirds majority and results in the removal of the federal official from public office.

The Senate has further oversight powers over the executive branch. For those, see United States Senate.

Officers of the Congress

The Constitution provides that the vice president shall be President of the Senate. The vice president has no vote, except in the case of a tie. The Senate chooses a President pro tempore to preside when the vice president is absent. The most powerful person in the Senate is not the president pro tempore, but the Senate Majority Leader.

The House of Representatives chooses its own presiding officer—the Speaker of the House. The speaker and the president pro tempore are always members of the political party with the largest representation in each house, aka the majority.

At the beginning of each new Congress, members of the political parties select floor leaders and other officials to manage the flow of proposed legislation. These officials, along with the presiding officers and committee chairpersons, exercise strong influence over the making of laws.

| Position | Senate | Current Office Holder | House | Current Office Holder |

| Presiding Officer | President of the Senate (symbolic) President pro tempore of the United States Senate (acting) | Dick Cheney Ted Stevens | Speaker of the United States House of Representatives | Dennis Hastert |

| Majority Leader | United States Senate Majority Leader | Bill Frist | Majority Leader of the United States House of Representatives | Tom DeLay |

| Minority Leader | United States Senate Minority Leader | Harry Reid | Minority Leader of the United States House of Representatives | Nancy Pelosi |

| Majority Whip | United States Senate Majority Whip | Mitch McConnell | Majority Whip of the United States House of Representatives | Roy Blunt |

| Minority Whip | United States Senate Minority Whip | Richard Durbin | Minority Whip of the United States House of Representatives | Steny H. Hoyer |

The committee process

One of the major characteristics of the Congress is the dominant role that Congressional committees play in its proceedings. Committees have assumed their present-day importance by evolution, not by constitutional design, since the Constitution makes no provision for their establishment. In 1885, when Woodrow Wilson wrote Congressional Government, there were only 60-odd legislative committees and subcommittees, in the 1990's there were 300. There are so many subcommittees that Morris Udall of Arizona could joke that he could address any Democrat whose name he had forgotten, "Good morning, Mr. Chairman," and half the time be right. (Frozen Republic, 191)

At present the Senate has 16 full-fledged standing (or permanent) committees; the House of Representatives has 20 standing committees. Each specializes in specific areas of legislation: foreign affairs, defense, banking, agriculture, commerce, appropriations, etc. Almost every bill introduced in either house is referred to a committee for study and recommendation. The committee may approve, revise, kill or ignore any measure referred to it. It is nearly impossible for a bill to reach the House or Senate floor without first winning committee approval. In the House, a petition to release a bill from a committee to the floor requires the signatures of 218 members; in the Senate, a majority of all members is required. In practice, such discharge motions only rarely receive the required support.

The majority party in each house controls the committee process. Committee chairpersons are selected by a caucus of party members or specially designated groups of members. Minority parties are proportionally represented on the committees according to their strength in each house.

Bills are introduced by a variety of methods. Some are drawn up by standing committees; some by special committees created to deal with specific legislative issues; and some may be suggested by the president or other executive officers. Citizens and organizations outside the Congress may suggest legislation to members, and individual members themselves may initiate bills. After introduction, bills are sent to designated committees that, in most cases, schedule a series of public hearings to permit presentation of views by persons who support or oppose the legislation. The hearing process, which can last several weeks or months, theoretically opens the legislative process to public participation.

One virtue of the committee system is that it permits members of Congress and their staffs to amass a considerable degree of expertise in various legislative fields. In the early days of the republic, when the population was small and the duties of the federal government were narrowly defined, such expertise was not as important. Each representative was a generalist and dealt knowledgeably with all fields of interest. The complexity of national life today calls for special knowledge, which means that elected representatives often acquire expertise in one or two areas of public policy.

US_House_Committee.jpg

When a committee has acted favorably on a bill, the proposed legislation is then sent to the floor for open debate. In the Senate, the rules permit virtually unlimited debate. In the House, because of the large number of members, the Rules Committee usually sets limits. When debate is ended, members vote either to approve the bill, defeat it, table it (which means setting it aside and is tantamount to defeat) or return it to committee. A bill passed by one house is sent to the other for action. If the bill is amended by the second house, a conference committee composed of members of both houses attempts to reconcile the differences.

Conference committees are not supposed to add anything that was not supported by either house, or delete anything that was supported by one house, but in practice conference committees make substantial changes to legislation. According to Citizens Against Government Waste, conference committees even add pork to legislation. For the 2005 budget conference committees added 3407 pork barrel appropriations, budget, up from 47 pork barrel appropriations in 1994.

Once passed by both houses, the bill is sent to the president, for constitutionally the president must act on a bill for it to become law. The president has the option of signing the bill—at which point it becomes national law—or vetoing it. A bill vetoed by the president must be reapproved by a two-thirds vote of both houses to become law, this is called overriding a veto.

The president may also refuse either to sign or veto a bill. In that case, the bill becomes law without his signature 10 days after it reaches him (not counting Sundays). The single exception to this rule is when Congress adjourns after sending a bill to the president and before the 10-day period has expired; his refusal to take any action then negates the bill — a process known as the "pocket veto."

Congressional powers of investigation

One of the most important nonlegislative functions of the Congress is the power to investigate. This power is usually delegated to committees—either to the standing committees, to special committees set up for a specific purpose, or to joint committees composed of members of both houses. Investigations are conducted to gather information on the need for future legislation, to test the effectiveness of laws already passed, to inquire into the qualifications and performance of members and officials of the other branches, and, on rare occasions, to lay the groundwork for impeachment proceedings. Frequently, committees call on outside experts to assist in conducting investigative hearings and to make detailed studies of issues.

There are important corollaries to the investigative power. One is the power to publicize investigations and their results. Most committee hearings are open to the public and are widely reported in the mass media. Congressional investigations thus represent one important tool available to lawmakers to inform the citizenry and arouse public interest in national issues. Congressional committees also have the power to compel testimony from unwilling witnesses and to cite for contempt of Congress witnesses who refuse to testify and for perjury those who give false testimony.

Informal practices of Congress

In contrast to European parliamentary systems, the selection and behavior of U.S. legislators has little to do with central party discipline. Each of the major American political parties is a coalition of local and state organizations that join together as a national party—Republicans and Democrats. Thus, traditionally members of Congress owe their positions to their districtwide or statewide electorate, not to the national party leadership nor to their congressional colleagues. As a result, the legislative behavior of representatives and senators tends to be individualistic and idiosyncratic, reflecting the great variety of electorates represented and the freedom that comes from having built a loyal personal constituency.

Congress is thus a collegial and not a hierarchical body. Power does not flow from the top down, as in a corporation, but in practically every direction. There is comparatively minimal centralized authority, since the power to punish or reward is slight. Congressional policies are made by shifting coalitions that may vary from issue to issue. Sometimes, where there are conflicting pressures—from the White House and from important interest groups—legislators will use the rules of procedure to delay a decision so as to avoid alienating an influential sector. A matter may be postponed on the grounds that the relevant committee held insufficient public hearings. Or Congress may direct an agency to prepare a detailed report before an issue is considered. Or a measure may be put aside by either house, thus effectively defeating it without rendering a judgment on its substance.

There are informal or unwritten norms of behavior that often determine the assignments and influence of a particular member. "Insiders," representatives and senators who concentrate on their legislative duties, may be more powerful within the halls of Congress than "outsiders," who gain recognition by speaking out on national issues. Members are expected to show courtesy toward their colleagues and to avoid personal attacks, no matter how unpalatable their opponents' policies may be, though in recent years this norm has been called into question. Still, members daily refer to one another as the "Gentlewoman from Tennessee" or the "distinguished Senator from Michigan," reflecting a traditionalist etiquette found in few other domains of American life. Members usually specialize in a few policy areas rather than claim expertise in the whole range of legislative concerns. Those who conform to these informal rules are more likely to be appointed to prestigious committees or at least to committees that affect the interests of a significant portion of their constituents.

A Congressional practice that is newly emerged is the practice of the Speaker of the House only supporting legislation that is supported by his party, regardless of whether or not he personally supports it or the majority of the House supports it. Dennis Hastert believes that the Speaker should only let pass legislation that is supported by the "majority of the majority," not necessarily the entire House. In a 2003 Capital speech Hastert said "On occasion, a particular issue might excite a majority made up mostly of the minority . . . Campaign finance is a particularly good example of this phenomenon. The job of speaker is not to expedite legislation that runs counter to the wishes of the majority of his majority." [[1] (http://www.washingtonpost.com/ac2/wp-dyn/A15423-2004Nov26?language=printer)]

The traditional independence of members of Congress has both positive and negative aspects. One benefit is that a system that allows legislators to vote their consciences or their constituents? wishes is inherently more democratic than one that does not. In European party systems legislators are beholden to the party leadership through the slating process, in America's party system they are responsible to voters through primaries.

The independence of Congressmen and Senators also allows much greater diversity of opinion than would exist if Congressmen had to obey their leaders. If legislators had to vote with the party leadership, presumably America would become a multi-party system. Thus although there are only two parties represented in Congress, America?s Congress represents virtually every shade of opinion that exists in the land. (see third party)

The problem of independence is that there is less accountability for voters than there would be if Congressmen took responsibility for their party?s actions.

When in the majority, congressional leaders in both houses and both parties use a technique that is sometimes called "catch and release." In "catch and release," if a piece of pending legislation is unpopular in a member?s district or state, that member of Congress will be allowed to vote against the law if his or her vote will not affect the outcome. If the vote will be close, Congressmen will be "reeled in" and required to vote for the party?s legislation. Because of catch and release, it is possible for Congressmen to hide their true political stances from their constituents until an extremely close vote comes up. As an example, in 2002, several members of Congress voted to authorize presidential Trade Promotion Authority, formerly known as "Fast Track," who had never voted for free trade in the past. Apparently, they had always supported free trade, but had been able to conceal it from their anti-trade constituents. On the 2003 Prescription Drug Benefit, 13 Republicans voted affirmatively in extremely close 6:00 AM initial vote only to vote against the conference bill when it returned a few weeks later, thereby being able to tell their constituents whatever they needed to tell them.

Congressional freedom of action also allows Congressmen and Senators to hold out on certain bills in order to pull down pork for their districts. Often a reluctant vote has to be won over by pet projects or jobs for allies. In the Senate, small state Senators are more likely to hold out than large state Senators are. Congressional freedom of action also gives more power to lobbyists. Compared to America, parliamentary nations have far fewer lobbyists per capita.

The practice of districts choosing their own Congressmen also results in members of Congress being the best fundraisers and best campaigners, not necessarily the best qualified.

Women in the 109th Congress

See also: Women in the United States Senate

The 109th Congress of the United States began in 2005 and will end in 2006.

White males have always predominated in the Congress, but the number of female members has gradually increased. In the 109th Congress, there are 69 women serving in the House of Representatives and 14 in the U.S. Senate. This is the greatest number of women to serve in Congress at one time. Rebekah Herrick, author of "Gender Effects on Job Satisfaction in the House of Representatives" comments on the traditional male dominance of the institution, saying: "Congress is a masculine institution in that it was created by men and is composed largely of men with a masculine bias that affects its power structure and norms today. Similarly, Congresswomen, even in the 1990s, see the House as a male institution and have complained about their difficulty in gaining positions of power, sexual harassment, patronizing behavior, and being left out of social and recreational opportunities."

Further reading

- Imbornoni, Ann-Marie; Johnson, David; and Haney, Elissa. "Famous Firsts by American Women" Infoplease. 2005. 03-01-05 <http://www.infoplease.com/spot/womensfirsts1.html>

- Herrick, Rebekah. "Gender effects on job satisfaction in the House of Representatives." Women and Politics 23.4 (2001), 85-98.

Lobbyists

Lobbying has been called the fourth branch of the American government. Many observers of Congress consider lobbying to be a corrupting practice, but others appreciate the fact that lobbyists provide information. Lobbyists also help write complicated legislation.

Lobbyists must be registered in a central database and only sometimes actually work in lobbies. Virtually every group - from corporations to foreign governments to states to grass-roots organizations - employs lobbyists.

In 1987, there were 23,000 registered lobbyists, a sixty-fold increase from 1961. (Power Game, Hendrick Smith, 29-31) Many lobbyists are former Congressmen and Senators, or relatives of sitting Congressmen. Former Congressmen are advantaged because they retain special access to the Capital, office buildings, and even the Congressional gym.

Elections

Elections for members of both houses of Congress are invariably held in November of every even numbered year, on that month's first Tuesday following its first Monday (that is to say, on the Tuesday that falls between the second and eighth days, inclusive), a day known as Election Day.

In the case of the House of Representatives, these elections occur in every state, and in every district of the states that are divided into Congressional districts. Occasionally a special election is held within a state, or district of a state, that has an unscheduled vacancy in its corresponding seat.

Candidates are generally chosen through primary elections. In some states, minor party candidates are chosen by political conventions. In Louisiana, runoff voting is used instead of a primary process.

In the case of the Senate, however, since terms of office last six years and each state has two, it follows mathematically that Senate elections can occur in a given state no more often than twice for every three Congressional-election years. In fact, no state has elections for both its senators in the same year (with possible exceptions in cases of unscheduled vacancies); every state elects one senator two years after the other, and then next elects a senator after four additional years. (One additional possible wrinkle remains: rarely, a state may divide itself into two Senate districts, with a Senate election occurring every sixth year in each district, and never in both districts in one year.) Replacements for vacant Senate seats are usually appointed by state governors, rather than by special election. Before the passage of the Seventeenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, providing for direct elections, Senators were chosen by state legislatures.

Seats by party (109th Congress, 2005-2007)

Senate

| + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| + | Republicans: 55 |

| + | Democrats: 44 |

| + | Independent: 1 (Senator James Jeffords (I-VT) votes with the Democrats on procedural matters) |

House of Representatives

| * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * |

| * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * |

| * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * |

| * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * |

| * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * |

| * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * |

| * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * |

| * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * |

| * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * |

| * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * |

| * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * |

| * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * |

| * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * |

| * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * |

| * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * |

| * | Republicans: 231 (53%) |

| * | Democrats: 202 (46%) |

| * | Independent: 1 (Bernard Sanders of VT) |

| * | Vacant: 1 (Rob Portman (R-OH-2) resigned on April 29, 2005 to become U.S. Trade Representative.) |

List of United States Congresses by Session

For a detailed list of congressional members or information on particular congressional sessions, click on a session's link from the List of United States Congresses.

Further reading

- Baker, Ross K., House and Senate (3rd Ed. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2000). ISBN 0393976114

- Davidson, Roger H., and Walter J. Oleszek, Congress and Its Members, 6th ed. Washington DC: Congressional Quarterly, Inc., 1998.

- Hunt, Richard, "Using the Records of Congress in the Classroom," OAH Magazine of History 12, (Summer 1998): 34-37. EJ 572 681.

- Lee, Frances and Bruce Oppenheimer, "Sizing Up the Senate: The Unequal Consequences of Equal Representation," University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1999.

- Rimmerman, Craig A. "Teaching Legislative Politics and Policy Making." Political Science Teacher 3 (Winter 1990): 16-18. EJ 409 538.

- Ritchie, Donald A, "What Makes a Successful Congressional Investigation," OAH Magazine of History 11 (Spring 1997): 6-8. EJ 572 628

External links

- U.S. House of Representatives (http://www.house.gov/)

- U.S. Senate (http://www.senate.gov/)

- Library of Congress: Thomas Legislative Information (http://thomas.loc.gov/)

- Teaching about the U.S. Congress (http://www.eric.ed.gov/ERICWebPortal/Home.portal?_nfpb=true&ERICExtSearch_SearchValue_0=Vontz&ERICExtSearch_SearchType_0=authors&_pageLabel=RecordDetails&objectId=0900000b801b5845)

- GovTrack.us (http://www.govtrack.us/) - a free research tool and a personalized Congress-tracker, consolidating information on bills, legislators, etc. from many sources in an open, extensible RDF framework.