Scottish Gaelic language

|

|

| Scottish Gaelic (Gàidhlig na h-Albann) | |

|---|---|

| Spoken in: | Scotland, Canada |

| Region: | Scottish Highlands, Western Isles, Cape Breton, Nova Scotia, Scottish cities, and formerly much of the Scottish Lowlands |

| Total speakers: | 58,652 (see also under External links below) |

| Ranking: | Not in top 100 |

| Genetic classification: | Indo-European |

| Official status | |

| Official language of: | Scotland |

| Regulated by: | Bòrd na Gàidhlig |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | gd |

| ISO 639-2 | gla |

| SIL | GLS |

| See also: Language – List of languages | |

Scottish Gaelic, Scots Gaelic, or just Gaelic (Gàidhlig; IPA: ), is a member of the Goidelic branch of Celtic languages. The branch includes Scottish Gaelic, Irish and Manx, and is distinct from the Brythonic branch, which includes Welsh, Cornish, and Breton. Scottish Gaelic, Manx and Irish are all descended from Old Irish. The language is often described as Scottish Gaelic, Scots Gaelic, or Gàidhlig to avoid confusion with the two other tongues. In Ireland it is sometimes erroneously called Scots, which in Scotland refers to the Scots language, related to English.

Gaelic is the traditional language of the Gaels, and the historical language of the majority of Scotland. It was brought to ancient Caledonia, on the island known as Alba, by Scots from what is now Ireland around A.D. 500. (Caledonia lies entirely within the modern country of Scotland.) The Gaelic language displaced the native Pictish, and until the late 15th century it was known in Inglis (the Anglian language of Scotland) as Scottis. By the early 16th century however, the Gaelic language had acquired the name Erse, meaning Irish, and it was the the Inglis language that came to be referred to as Scottis (today's Scots or Scottish). Nonetheless, Gaelic still occupies a special place in Scottish culture, and is recognised by many Scots, whether or not they speak Gaelic, as being a part of the nation's culture, though others may view it primarily as a regional language of the highlands and islands.

Gaelic has a rich oral (beul aithris) and written tradition, having been the language of the bardic culture of the Highland clans for several centuries, and the survival of Gaelic has been therefore a very important factor in Scottish politics. The language preserved knowledge of and adherence to pre-feudal (tribal) laws and customs (as represented, for example, by the expressions tuatha and duthchas). Where the language survived, therefore, people were stubbornly resistant to the rule of a lowland-centred and Scottis-speaking Scottish state. This stubbornness was not seriously overcome until after the Scottish state had become allied with England. The language suffered especially as Highlanders and their traditions were persecuted after the Battle of Culloden in 1746, and during the Highland Clearances, but pre-feudal attitudes were still evident in the complaints and claims of the Highland Land League of the late 19th century: this political movement was successful in getting members elected to the Parliament of the United Kingdom. The Land League was dissipated as a parliamentary force by the 1886 Crofters' Act and by the way the Liberal Party was seen to become supportive of Land League objectives.

Scottish Gaelic may be more correctly known as Highland Gaelic to distinguish it from the now defunct Lowland Gaelic. Lowland Gaelic was spoken in the southern regions of Scotland prior to the introduction of Lowland Scots. There is, however, no evidence of a linguistic border following the topographical north-south differences. Similarly, there is no evidence from placenames of significant linguistic differences between, for example, Argyll and Galloway. Dialects on both sides of the Straits of Moyle linking Scottish Gaelic with Irish are now extinct.

| Contents |

Orthography

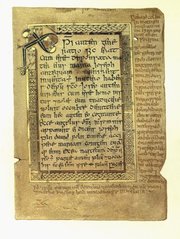

Sanas.jpg

The modern Scottish Gaelic alphabet has 18 letters:

- A, B, C, D, E, F, G, H, I, L, M, N, O, P, R, S, T, U

The letter h, now mostly used to indicate lenition of a consonant, was not used in the oldest orthography, as lenition was instead indicated with a dot over the lenited consonant. Letters of the alphabet were traditionally named after trees: ailm (elm), beith (birch), coll (hazel), dair (oak), and so on, but this custom is no longer followed.

The quality of consonants is partially indicated by the vowels surrounding them. The vowels are classified as caol ("slender", i.e. e and i) or leathann ("broad", i.e. a, o and u). The spelling rule is caol ri caol is leathann ri leathann (slender to slender and broad to broad). Slender consonants are palatalised while broad consonants are velarised.

Because of the spelling rule, an internal consonant group must be surrounded by vowels of the same quality to indicate its pronunciation unambiguously, since some consonants change their pronunciation depending on whether they are surrounded by broad or slender vowels: for example, compare the t in slàinte with the t in bàta .

Mallaig_sign.jpg

The rule has no effect on the pronunciation of vowels. For example, plurals in Gaelic are often formed with the suffix -an, for example, bròg (shoe)/brògan (shoes). But because of the spelling rule, the suffix is spelled -ean (but pronounced the same) after a slender consonant, as in taigh (house)/taighean (houses).

In changes promoted by the Scottish Examination Board from 1976 onwards, certain modifications were made to this rule. For example, the suffix of the past participle is always spelled -te, even after a broad consonant, as in togte 'raised' (rather than the traditional togta).

Using the spelling rule, it is sometimes unclear whether a vowel has been introduced for its own pronunciation or for its effect upon a consonant.

Unstressed vowels omitted in speech can be omitted in informal writing. e.g.,

- Tha mi an dòchas (I hope) > Tha mi 'n dòchas

Once Gaelic orthographic rules have been learned, the pronunciation of the written language can be seen to be quite predictable. However learners must be careful not to try to apply English spelling rules to written Gaelic, otherwise mispronunciations will result. Gaelic personal names such as Seònaid are especially likely to be mispronounced when they are used by English speakers.

Pronunciation

Most letters are pronounced similarly to other European languages. The broad consonants t and d and often n have a dental articulation (as in Irish and the Romance and Slavic languages) in contrast to the alveolar articulation common in English and other Germanic languages). Non-palatal r is an alveolar trill (like Italian r or Spanish rr.)

The "voiced" stops b, d, g are not voiced at all in Gaelic, but are rather voiceless unaspirated. The "voiceless" stops p, t, c are voiceless and strongly aspirated (postaspirated in initial position, preaspirated in final position). Gaelic shares this property with Icelandic. In Gaelic, stops at the beginning of a stressed syllable become voiced when they follow a nasal consonant, e.g. taigh 'a house' is but an taigh 'the house' is ; cf. also tombaca 'tobacco' .

The lenited consonants have special pronunciations: bh and mh are ; ch is or ; dh, gh is or ; th is , , or silent; ph is . Lenition of l n r is not shown in writing.

fh is almost always silent, with only the following three exceptions: fhèin, fhathast, and fhuair, where it is pronounced as .

| Consonant | Normal | Lenited | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Broad | Slender | Broad | Slender | |

| b | ||||

| c | ||||

| d | ||||

| f | silent | silent | ||

| g | ||||

| l | ||||

| m | ||||

| n | ||||

| p | ||||

| r | ||||

| s | ||||

| t |

There are a few general features worth noting.

- Stress is usually on the first syllable: e.g. drochaid 'a bridge' ().

(Knowledge of this fact alone would help avoid many a mispronunciation of Highland placenames, e.g. Mallaig is . Note, though, that when a placename consists of more than one word in Gaelic, that the Anglicised form can have stress elsewhere: Tyndrum () < Taigh an Droma ().

- A distinctive characteristic of Gaelic pronunciation (which has influenced the Scottish accent — cf. girl and film ) is the insertion of epenthetic vowels between certain adjacent consonants, specifically, between sonorants (l or r) and certain following consonants:

- tarbh (bull) —

- Alba (Scotland) — .

- Schwa () at the end of a word is dropped when followed by a word beginning with a vowel. For example,

- duine (a man) —

- an duine agad (your man) —

Grammar

Scottish Gaelic is an inflected language. Nouns indicate their relationships with a number of grammatical cases (nominative, dative, genitive, and vocative), and verbs are conjugated to indicate tense (simple tenses are past and future; compound tenses are continuous present, past, and future), mood (indicative, imperative, subjunctive), and voice (active, passive).

Gaelic shares with other Celtic languages a number of interesting grammatical features:

- Verb Subject Object word order; a relatively uncommon typology among the world's languages

- Prepositional pronouns: pronouns and most prepositions are fused into compound forms, such as agam (at me), agad (at you), ris (to him).

- The absence of a verb to have: instead, possession is expressed prepositionally, with aig (i.e. by saying that something is at or on a person, cf. Russian u):

- tha taigh agam — I have a house (lit. a house is at me)

- an cat aig Iain — John's cat (lit. the cat at John)

- Emphatic pronouns: A distinction is made between the ordinary pronouns, like mi and thu, and their emphatic counterparts, mise and thusa, etc., which express a contrast to other persons. For example:

- tha i bòidheach — she's beautiful

- tha ise bòidheach — she's beautiful (as opposed to somebody else)

Grammatical emphasis carries over into other situations:

- an taigh aicese — her house

- chuirinnsa — I would put

- na mo bheachd-sa — in my opinion

- "To be": Gaelic has two forms of the verb "to be": tha is used to ascribe a property to a noun or pronoun, whereas in general usage is is used to identify a noun or pronoun as a complement. ('Is' can be used to ascribe a description to a noun or pronoun, but generally this usage is restricted to fixed expressions, e.g. 'Is beag an t-iongnadh' lit. 'Is small the surprise'

- tha mise sgìth — I am tired

- is mise Eòghann — I am Ewen.

It is, however, possible to use tha to say that one thing is another thing by turning it into a property:

- tha mi nam Albannach — I am a Scot (lit. I am in my Scot)

- Is e Albannach a th' annam — I am a Scot (lit. it's a Scot that's in me).

Articles

Gaelic has a definite article but no indefinite article:

- an taigh — 'the house'

- taigh — '(a) house'

The form of the (definite) article depends on the number, gender, case, and initial sound of the noun.

(i). an, am, and an t- are used with masculine singular nominative nouns:

- an cat — 'the cat' (also for nouns which cannot be lenited)

- am balach — 'the boy' (nouns which begin with labial consonants)

- an t-òran — 'the song' (nouns which begin with vowels)

(ii). a' is used before a lenited consonant; there are two cases:

- a' chaileag — 'the girl' (feminine nominative and dative)

- leis a' bhalach — 'with the boy' (masculine dative and genitive)

(iii). na and na h- (before a vowel) are used in the feminine genitive singular:

- na mara — 'of the sea'

- na h-Alba — 'of [the] Scotland'

(iv). na and na h- (before a vowel) are used in the nominative and dative plural of both genders:

- na cait — 'the cats'

- na h-àireamhan — 'the numbers'

(v). nan or nam (before a labial) are used in the genitive plural:

- nan cat — 'of the cats'

- nam balach — 'of the boys'

Official Recognition

Parlamaid_na_h-Alba_Doras_BPA_200411_CopyrightKaihsuTai.jpg

After centuries of official discouragement, Gaelic has now achieved a degree of official recognition with the passage of the Gaelic Language (Scotland) Act.

As well as being taught in schools, including some in which it is the medium of instruction, it is also used by the local council in the Western Isles, Comhairle nan Eilean. The BBC also operates a Gaelic language radio station Radio nan Gaidheal (which regularly transmits joint broadcasts with its Irish counterpart Raidió na Gaeltachta), and there are also television programmes in the language on the BBC and on the independent commercial channels, usually subtitled in English. The ITV franchisee in the north of Scotland, Grampian Television, has a studio in Stornoway.

However, a separate Gaelic language TV service, similar to S4C in Wales and TG4 in Ireland, has been under consideration. As in Wales, the showing of programmes in the language as opt-outs on the main channels has been regarded as inadequate for the 58,552 who speak it, and as an annoyance to some of the English or Scots speaking 5,003,459 who do not. In fact, this annoyance may be largely assumed: the evidence is that at least one Gaelic television programme produced by the BBC attains viewing figures in excess of the number of Gaelic speakers that could view it in Scotland. No complaints are being received by the BBC about Gaelic-language television programmes on BBC TV channels, perhaps because subtitling them in English makes them equally accessible to non-Gaelic speakers.

Gaelic road signs are gradually being introduced throughout the Highlands and elsewhere across the nation. In many cases, this has simply meant adopting the correct spelling of a name but, even here, anti-Gaelic prejudice has had to be overcome. Most non-Gaels are unaware of the extent to which anti-Gaelic prejudice and sheer racism are prevalent in Scotland. Newspaper columnists regularly mock Gaelic language and culture, propagating stereotypes in a way which would be unimaginable for other groups, and openly call for all funding to be cut.

The Ordnance Survey has acted in recent years to correct many of the mistakes that appear on maps. They announced in 2004 that they intended to make amends for a century of Gaelic ignorance and set up a committee to determine the correct forms of Gaelic place names for their maps.

Historically, Gaelic has not received the same degree of official recognition from the UK Government as Welsh. With the advent of devolution, however, Scottish matters have finally begun to receive greater attention, and the Gaelic Language (Scotland) Act was confirmed by the Scottish Parliament on 21 April 2005.

The key provisions of the Act are:

- Recognising in legislation Gaelic as an official language of Scotland with 'equal respect' to English

- Establishing the Gaelic development body, Bòrd na Gàidhlig, on a statutory basis to promote the use and understanding of Gaelic

- Requiring Bòrd na Gàidhlig to prepare a National Gaelic Language Plan for approval by Scottish Ministers

- Requiring Bòrd na Gàidhlig to produce guidance on Gaelic Education for education authorities.

- Requiring public bodies in Scotland, both Scottish public bodies and cross border public bodies insofar as they carry out devolved functions, to consider the need for a Gaelic language plan in relation to the services they offer.

FailteGuSteiseanDunEideann20041127_CopyrightKaihsuTai.jpg

Following a consultation period, in which the government received many submissions, the majority of which asked that the bill be strengthened, a revised bill was published with the main improvement that the guidance of the Bòrd is now statutory (rather than advisory).

In the committee stages in the Scottish Parliament, there was much debate over whether Gaelic should be given 'equal validity' with English. Due to Executive concerns about resourcing implications if this wording was used, the Education Committee settled on the concept of equal respect.

The Act was passed by the Scottish Parliament unanimously, with support from all sectors of the Scottish political spectrum on the 21st of April 2005.

The Education Act of 1872, which completely ignored Gaelic, and led to generations of Gaels being forbidden to speak their native language in the classroom, is now recognised as having dealt a major blow to the language.

The first solely Gaelic medium secondary school will open in Glasgow in 2005 (several Gaelic medium primary schools and partially Gaelic medium secondary schools already exist).

In Nova Scotia, there are somewhere between 500 and 1,000 native speakers, most of them now elderly. In May 2004, the Provincial government announced the funding of an initiative to support the language and its culture within the province.

The UK government has ratified the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages in respect of Gaelic.

The Columba Initiative, also known as Iomairt Cholm Cille, is a body that seeks to promote links between speakers of Scottish Gaelic and Irish.

Place names

- Aberdeen — Obar Dheathain

- Dumfries — Dùn Phris

- Dundee — Dùn Dèagh

- Edinburgh — Dùn Èideann

- Fort William — An Gearasdan

- Glasgow — Glaschu

- Inverness — Inbhir Nis

- Paisley — Pàislig

- Perth — Peairt

- Stirling — Sruighlea

- Stornoway — Steòrnabhagh

Personal Names

Gaelic has a number of personal names, such as Aonghas, Dòmhnall, Donnchadh, Coinneach, Murchadh, for which there are traditional forms in English (Angus, Donald, Duncan, Kenneth, Murdo). There are also distinctly Scottish Gaelic forms of names that belong to the common European stock of given names, such as: Iain (John), Alasdair (Alexander), Uilleam (William), Caitrìona (Catherine), Cairistìona (Christina), Anna (Ann), Màiri (Mary). Some names have come into Gaelic from Old Norse, e.g. : Somhairle ( < Somarliðr), Tormod (< Þórmóðr), Torcuil (< Þórkell, Þórketill), Ìomhair (Ívarr). These are conventionally rendered in English as Sorley (or, historically, Somerled), Norman, Torquil, and Iver (or Evander). There are other, traditional, Gaelic names which have no direct equivalents in English: Oighrig, which is normally rendered as Euphemia (Effie) or Henrietta (Etta) (formerly also as Henny or even as Harriet), or, Diorbhal, which is "matched" with Dorothy, simply on the basis of a certain similarity in spelling; Gormul, for which there is nothing similar in English, and it is rendered as 'Gormelia' or even 'Dorothy'!; Beathag, which is "matched" with Becky (> Rebecca) and even Betsy!, or Sophie.

Many of these are now regarded as old-fashioned, and are no longer used (which is, of course, a feature common to many cultures: names go out of fashion). As there is only a relatively small pool of traditional Gaelic names from which to choose, some families within the Gaelic-speaking communities have in recent years made a conscious decision when naming their children to seek out names that are used within the wider English-speaking world. These names do not, of course, have an equivalent in Gaelic. What effect that practice (if it becomes popular) might have on the language, remains to be seen. At this stage (2005), it is clear that some native Gaelic-speakers are willing to break with tradition. Opinion on this practice is divided, whilst some would argue that they are thereby weakening their link with their linguistic and cultural heritage, others take the opposing view that Gaelic, as with any other language, must retain a degree of flexibility and adaptability if it is to survive in the modern world at all.

The well-known name Hamish, and the recently established Mhairi (pronounced as if Vaary) come from the Gaelic for, respectively, James, and Mary, but derive from the form of the names as they appear in the vocative case: Seumas (James) (nom.) -> Sheumais (voc.), and, Màiri (Mary) (nom.) -> Mhàiri (voc.).

The most common form of Gaelic surname is, of course, those beginning with mac (Gaelic for son), such as MacGillEathain (MacLean). The female form is nic, so Catherine MacPhee is properly called in Gaelic, Caitrìona Nic a' Phì.

Several colours give rise to common Scottish surnames: bàn (Bain - white), ruadh (Roy - red), dubh (Dow - black), donn (Dunn - brown).

Loanwords

The majority of Scots Gaelic's vocabulary is native Celtic. There is a number of borrowings from Latin, (muinntir, Didòmhnaich), ancient Greek, especially in the religious domain (eaglais, Bìoball from Ekklesia & Biblos), Norse (eilean, sgeir), Hebrew (Sàbaid, Aba) and Lowland Scots (briogais, aidh).

Attempts have been made to bring its vocabulary up to date by creating new words to deal with modern concepts, but in fact the English word is normally adopted and an attempt is made to clothe the word in Gaelic orthography - not always successfully: television, for instance, becomes telebhisean; computer becomes coimpiùtar. Although native speakers frequently use an English word for which there is a perfectly good Gaelic equivalent, they will, without thinking, simply adopt the English word and use it, applying the rules of Gaelic grammar, as the situation requires. With verbs, for instance, they will simply add the verbal suffix (-eadh, or, in Lewis, -igeadh, as in, Tha mi a' watcheadh (Lewis, watchigeadh) an telly (I am watching the television). This is seen as a worrying trend by some native speakers, but it is interesting to note that this very same feature was remarked upon by the minister who compiled the account covering the parish of Stornoway in the New Statistical Account of Scotland, published over 170 years ago!

Going in the other direction, Scottish Gaelic has influenced Lowland Scots (gob) and English, particularly Scottish Standard English. Loanwords include: whisky, slogan, brogue, jilt, clan, strontium, trousers, as well as familiar elements of Scottish geography like ben (beinn), glen (gleann) and loch. Irish Gaelic has also influenced Lowland Scots and English in Scotland, but it is not always easy to distinguish its influence from that of the Scottish variety. See List of English words of Scottish Gaelic origin

Source: An Etymological Dictionary of the Gaelic Language, Alexander MacBain.

See also

- Gaidhealtachd

- Differences between Scottish Gaelic and Irish

- Not to be confused with Lowland Scots, the Germanic language of Lowland Scotland

- The Mòd, the preeminent Scottish Gaelic cultural festival.

- Languages in the United Kingdom

- Book of Deer

- William J. Watson, Gaelic scholar

- Walter Scott MacFarlane

External Links

- Scottish Parliament (http://www.scottish.parliament.uk/gaidhlig/)

- Scottish Gaelic Broadcasting Committee (http://www.ccg.org.uk)

- BBC Scotland - Scottish Gaelic homepage (http://www.bbc.co.uk/scotland/alba/)

- BBC Scotland - Beag air Bheag (http://www.bbc.co.uk/scotland/alba/foghlam/beag_air_bheag/) Scottish Gaelic for beginners

- Comunn na Gàidhlig (http://www.cnag.org.uk/)

- Iomairt Cholm Cille/The Columba Initiative (http://www.colmcille.net/)

- Sabhal Mòr Ostaig (http://www.smo.uhi.ac.uk/)

- Scottish Gaelic - English Dictionary (http://www.websters-online-dictionary.org/definition/Scottish-english/)

- Goidelic Dictionaries (http://www.ceantar.org/Dicts/search.html)

- AmBaile.org - Home of Highland Gaelic culture (http://www.ambaile.org) With some nice online games for Scottish Gaelic learners

- Scottish Gaelic (http://www.omniglot.com/writing/gaelic.htm) at Omniglot

- Learners' material online (http://www.smo.uhi.ac.uk/gaidhlig/ionnsachadh/)

- Census 2001 Scotland: Gaelic Language : first results, by Prof. Kenneth MacKinnon (2003) (http://'lrrc3.sas.upenn.edu/popcult/CLPP/Census%202001%20-%20Gaelic1.htm') which quotes the official figure of 58652 speakers and, if we include people professing an ability to understand/read/write Gaelic then that becomes 92396. - Website valid at 25 March 2005

- The Registrar General for Scotland's Report to Parliament (2003) (http://'www.gro-scotland.gov.uk/statistics/census/censushm/scotcen/scotcen2/scotcen4.html')

- Language studies about the local distribution of Gaelic speakers in North-West Scotland from 1881 until today (http://www.linguae-celticae.org/GLS_english.htm) (27 volumes covering Hebrides and Highlands including Perthshire, Caithness and Arran)

- Gaelic in Scotland (http://www.siliconglen.com/Scotland/gaelic.html) information and links from the Scottish FAQ.

- SaveGaelic.org (http://www.savegaelic.org) Gaelic supporters portal includes an extremely popular and active forum.

- Ethnologue report on Scots Gaelic – ISO 639 code GLA (http://www.ethnologue.com/show_language.asp?code=gla)

- Ethnologue report on Hiberno-Scottish – ISO 639 code GHC (http://www.ethnologue.com/show_language.asp?code=ghc)ast:Gaélicu escocés

ca:Llengua Celta cy:Gaeleg yr Alban de:Schottisch-Gälische Sprache es:Gaélico escocés eo:Skotgaela lingvo fr:Écossais ga:Gaeilge na hAlban gd:Gàidhlig li:Sjots Gaelic nl:Schots-Gaelisch pl:Język szkocki gaelicki sco:Gaelic leid sv:Skotsk-Gaeliska wa:Gayelike_escôswès zh:蘇格蘭蓋爾語