Scottish clan

|

|

Scottish clans give a sense of identity and shared descent to people in Scotland and to their relations throughout the world, with a formal structure of Clan Chiefs officially registered with the court of the Lord Lyon, King of Arms which controls the heraldry and Coat of arms. Each clan has its own tartan patterns, and those identifying with the clan can wear kilts of the appropriate tartan as a badge of membership and as a uniform where appropriate.

Clans identify with geographical areas originally controlled by the Chiefs, usually with an ancestral castle, and clan gatherings form a regular part of the social scene.

| Contents |

Origins of the clans

The word clann in Gaelic means family or children. Each clan was a large group of geographically related people, theoretically an extended family, supposedly descended from one progenitor, and all owing allegiance to the patriarchal clan chief. It also included a large group of loosely-related septs – related families or outside groups, all of whom looked to the clan chief as their head – and for their protection.

Some clans such as Clan Campbell and Clan Macdonald claim ancient Celtic mythological progenitors mentioned in the Fenian cycle, with a group including Macsween, Lamont and MacNeil tracing their ancestry back to the 5th century High King of Ireland. Others such as McKinnon and McGregor claim descent from the Scots King Kenneth Mac Alpin who made himself King of the Picts in 843, founding the Kingdom known as Alba. The Macdonalds and MacDougalls claim descent from the hybrid Viking / Gael Lord of the Isles related to Norse settlers in the west coast and islands.

The clans emerged from the turmoil of the 12th century and 13th century when the Scottish crown pacified northern rebellions and re-conquered areas taken by the Norse, and after the fall of Macbeth the crown became increasingly Anglo / Norman. This turmoil created opportunities for Celtic, Norse / Gael and British warlords with their kin to dominate areas, and the instability of the Wars of Scottish Independence brought in warlords with Anglo-Norman, Anglian and Flemish ancestry, founding clans such as the Camerons, Frasers, Chisholms, Menzies and Grants.

The Highland clan system

Inheritance and authority

The Scottish Highland clan system incorporated the Celtic / Norse traditions of heritage as well as Norman Feudal society. Chieftains and petty kings under the suzerainty of a High King ruled Gaelic Alba, with all such offices being filled through election by an assembly. Usually the candidate was nominated by the current office holder on the approach of death, and his heir-elect was known as the tanist, from the Gaelic tanaiste, or second, with the system being known as tanistry. This system combined a hereditary element with the consent of those ruled, and while the succession in clans later followed the feudal rule of primogeniture, the concept of authority coming from the clan continued.

Thus the collective heritage of the clan, the duthchas, gave the right to settle the land to which the chiefs and leading gentry provided protection and authority as trustees for the people. This was combined with the complementary concept of oighreachd where the chieftain's authority came from charters granted by the feudal Scottish crown, where individual heritage was warranted. While duthchas held precedence in the medieval period, the balance shifted as Scots law became increasingly important in shaping the structure of clanship.

Legal process

To settle criminal and civil disputes within clans both sides put their case to an arbitration panel drawn from the leading gentry of the clan and presided over by the chief. Similarly, in disputes between clans the chiefs served as procurators (legal agents) for the disputants in their clan and put the case to an arbitration panel of equal numbers of gentry from each clan presided over by a neighbouring chief or landlord. There was no appeal from the decision which awarded reparations, called assythment, to the wronged party and which was recorded in a convenient Royal or Burgh court. This compensation took account of the age, responsibilities and status of the victim as well as the nature of the crime, and once paid precluded any further action for redress against the perpetrator. To speed this process clans made standing provisions for arbitration and regularly contracted bands of friendship between the clans which had the force of law and were recorded in a convenient court.

Social ties

Fosterage and manrent were the most important forms of social bonding in the clans. In fosterage, the chief's children were brought up by favoured members of the leading clan gentry, whose children in turn were brought up by other favoured members of the clan. This brought about intense ties and reinforced clan cohesion. Manrent was a bond contracted by the heads of families looking to the chief for territorial protection, though not living on the estates of the clan elite. These bonds were reinforced by calps, death duties paid to the chief as a mark of personal allegiance by the family when their head died, usually in the form of their best cow or horse. Although calps were banned by Parliament in 1617, manrent continued covertly to pay for protection.

Less durably, marriage alliances reinforced kinship within clans and links to neighbouring clans. These were contracts involving the exchange of livestock, money and rent, tocher for the bride and dowry for the groom.

Clan management

Payments of rents and calps from those living on clan estates and calps alone from families living elsewhere were channelled through tacksmen. These lesser gentry acted as estate managers, allocating the run-rig strips of land, lending seed-corn and tools and arranging droving of cattle to the Lowlands for sale, taking a minor share of the payments made to the clan nobility, the fine. They had the important military role of mobilising the Clan Host, both when required for warfare and more commonly as a large turn out of followers for weddings and funerals, and traditionally in August for hunts which included sports for the followers, the predecessors of the modern Highland games.

From the late 16th century the Scottish Privy Council, recognising the need for co-operation, required clan leaders to provide bonds of surety for the conduct of anyone on their territory and to regularly attend at Edinburgh, encouraging a tendency to become absentee landlords. With an increase in droving, tacksmen acquired the wealth to finance the gentry's debts secured against their estates, hence acquiring the land. By the 1680s this led to the land in ownership largely coinciding with the collective duthchas for the first time. The tacksmen became responsible for the bonds of surety leading to a decline in banditry and feuding.

Disputes and disorder

Where the oighreachd, land owned by the clan elite or fine, did not match the common heritage of the duthchas this led to territorial disputes and warfare. The fine resented their clansmen paying rent to other landlords, while acquisitive clans used disputes to expand their territories, and many clan histories record ferocious long lasting feuding. On the western seaboard clans became involved with the wars of the Irish Gaels against the Tudor English, and a military caste called the buannachan developed, seasonally fighting in Ireland as mercenaries and living off their clans as minor gentry, but this was brought to an end with the Irish Plantations of James VI of Scotland and I of England. During that century law increasingly settled disputes, and the last feud leading to a battle was in Lochaber on August 4 1688.

Reiving had been a rite of passage, the creach where young men took livestock from neighbouring clans. By the 17th century this had declined and most reiving was the spreidh where up to 10 men raided the adjoining Lowlands, the livestock taken usually being recoverable on payment of tascal (information money) and guarantee of no prosecution. Some clans offered the Lowlanders protection against such raids, on terms not dissimilar to blackmail.

Although by the late 17th century disorder declined, reiving persisted with the growth of cateran bands of up to 50 bandits, usually led by a renegade of the gentry, who had thrown off the constraints of the clan system. As well as preying off the clans, caterans acted as mercenaries for Lowland lairds pursuing disputes amongst themselves.

Civil wars and Jacobitism

As the civil wars of the Three Kingdoms broke out in the early 17th century the Covenanters were supported by the territorially ambitious Argyll Campbells and House of Sutherland as well as some clans of the central Highlands opposed to the Royalist House of Huntly. While some clans remained neutral, others led by Montrose supported the Royalist cause, projecting their feudal obligations to clan chiefs onto the Royal House of Stuart, resisting the demands of the Covenanters for commitment and reacting to the ambitions of the larger clans. In the Scottish Civil War of 1644-47, the most prominent Royalist clan were Clan Donald led by Alasdair MacColla

With the Restoration of Charles II Episcopalianism became widespread among clans, which suited the hierarchical clan structure and encouraged obedience to Royal authority, some others were converted by Catholic missions. In 1682 James Duke of York, Charles' brother, instituted the Commission for Pacifying the Highlands which worked in co-operation with the clan chiefs in maintaining order as well as redressing Campbell acquisitiveness, and when he became King James VII he retained popularity with many Highlanders. All these factors contributed to continuing support for the Stuarts when James was deposed by William of Orange in the "Glorious Revolution".

The support among many clans, their remoteness from authority and the ready mobilisation of the clan hosts made the Highlands the starting point for the Jacobite Risings. In Scottish Jacobite ideology the Highlander symbolised patriotic purity as against the corruption of the Union, and as early as 1689 some Lowlanders wore "Highland habit" in the Jacobite army. In contrast, despite relying on support from Presbyterian clans the government depicted Highlanders as frightening savages who ate babies.

Decline of the Clan system

Successive Scottish governments had portrayed the clans as bandits needing occasional military expeditions to keep them in check and extract taxes. As Highlanders became associated with Jacobitism and rebellion the government made repeated efforts to curb the clans. Culminating after the battle of Culloden with a brutal repression. This followed in 1746 with the Act of Proscription, further measures making restrictions on their ability to bear arms, traditional dress, culture, and even music. The Heritable Jurisdictions Act removed the feudal authority the Clan Chieftains had once enjoyed.

With the failure of Jacobitism the clan chiefs and gentry increasingly became landlords, losing the traditional obligations of clanship. Becoming incorporated into the British aristocracy, looking to the clan lands to provide suitable income. From around 1725 clansmen had been immigrating to America with clan gentry looking to re-establish their lifestyle, or as victims of raids on the Hebrides looking for cheap labor. Increasing demand in Britain for cattle and sheep led to higher rents with surplus, clan population leaving in the mass migration later known as the Highland Clearances, finally undermining the traditional clan system.

Romantic "revival" of interest

The Ossian poems of James Macpherson in the 1760s suited the Romantic enthusiasm for the "sublime" "primitive" and achieved international success with a disguised elegy for the Jacobite clans, set in the remote past. Following the writings of Sir Walter Scott as well as the pomp surrounding the visit of King George IV to Scotland in 1822 spurred 19th century interest in the clans and a reawakening of Scottish culture and pride.

Soon after the Dress Act restricting kilt wearing was repealed in 1782, Highland aristocrats set up Highland Societies in Edinburgh and other centres including London and Aberdeen, landowners' clubs with aims including "Improvements" (which others would later call the Highland Clearances). Later clubs like the Celtic Society of Edinburgh included Highland chieftains and Lowlanders taking an interest in the clans.

Lowland clans

The central and southern Lowlands had been Brythonic Celtic, with the southeast coming under the Angles, then by 1034 Alba had expanded to bring the whole area under Gaelic Celtic rule. From 1124 King David I began the spread of Scots to the whole of the Lowlands, while the Highlands remained Gaelic under the Clan System. The term clan was still being used of Lowland families at the end of the 16th century and, while aristocrats may have been increasingly likely to use the word family, the terms remained interchangeable until the 19th century.

By the late 18th century the Lowlands were integrated into the British system, with an uneasy relationship to the Highlanders. The total population of Lowlanders diminished drastically in some parts of the south as a direct result of the Agricultural Revolution. That resulted in the Lowland Clearances, and the subsequent emigration of large numbers of Lowland Scots.

However, with the revival of interest in Gaeldom and the visit of King George IV to Scotland in 1822, there was a new enthusiasm amongst Lowlanders for identification with the Highlands. As a result many Lowland families and aristocrats now appear on clan lists with their own tartans, in some cases with a claim to ancestry from the Highland area – encouraged, no doubt, by companies who market supposed coats-of-arms and heraldic devices, manufacturers of tartan cloth, and by the immense growth of Internet genealogical research, beginning in the last few years of the twentieth century. As a result, many of these families now have their own clan societies, websites and annual reunions.

Clan membership, tartans and badges

The article Clans, Families and Septs (http://www.electricscotland.com/webclans/clans_families_septs.htm) by Sir Crispin Agnew of Lochnaw Baronet, Queens Counsel, Rothesay Herald of Arms (ie one of the four most senior members of the Lord Lyon's court), states that the terms clan and family are interchangeable, and makes it clear that membership is determined by the chief of the clan or family, who can accept or reject those who offer their allegiance. Historically the clan was those living on the chief's territory, though certain of his immediate family owed him allegiance wherever they lived. With changes in clan boundaries or migration of families the clan could include members with other surnames. A chief could add to his clan by adopting other families, and also had the legal right to outlaw anyone from his clan, including members of his own family. In modern terms a chief can accept whom he wants to, or limit clan membership to those with particular surnames. Those who have the chief's surname are deemed to be clan members, and anyone who offers allegiance to the chief by joining his clan society or wearing his clan tartan is considered a member unless disallowed by the chief, individually or by name group. Many people nowadays wish to claim clan membership on their mother's side, and while Sir Crispin does not mention this situation, there seems to be no reason for them not to offer allegiance to the chief of their mother's clan.

Where clans included groups with other surnames these are often listed as septs, but while the clan or family is a legally recognised group, sept lists have no official authority and merely reflect an estimate of historical associations.

Official Clan tartans are authorised by the chief and registered by the Lord Lyon, but there is no legal prohibition against wearing the "wrong" tartan. Originally there appears to have been little association of tartans with particular clans or areas, but the idea gained currency in the late 18th century and in 1815 the Highland Society of London began the naming and registration of "official" clan tartans, and gradually the original belted plaid was supplanted by the modern tailored kilt. For more information see Tartan and Kilt.

A sign of allegiance between clans is represented badges, and both clans and families have heraldic Coats of arms controlled by the Lord Lyon Court. In principle these badges should only be used with the permission of the clan chief and the Lyon Court has intervened in cases where permission has been withheld.

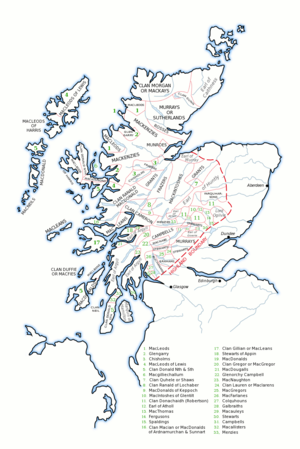

Clan lists and maps

The revival of interest, and demand for clan ancestry, has led to the production of lists and maps covering the whole of Scotland giving clan names and showing territories, sometimes with the appropriate tartans. While some lists and clan maps confine their area to the Highlands, others also show Lowland clans or families. Territorial areas and allegiances changed over time, and there are also differing decisions on which (smaller) clans and families should be omitted. Some alternative online sources are listed in the External links section below.

This list of Clans, with Chiefs where they are known, contains clans registered with the Lord Lyon Court. The Lord Lyon Court defines a clan or family as a legally recognised group, but does not differentiate between Families and Clans.

| Clan | Chief | Motto | Background |

| Agnew | Sir Crispin Agnew of Lochnaw, 11th Bt. | Consilio non impetu | |

| Anstruther | Sir Ian Anstruther of that Ilk, 8th and 13th Bt. | Periissem ni periissem | |

| Arbuthnott | John Campbell Arbuthnott, 16th Viscount of Arbuthnott | Laus Deo | |

| Bannerman | David Gordon Bannerman of Elsick, 15th Baronet | Pro Patria | |

| Barclay | Peter Barclay of Towie Barclay and of that Ilk | Aut agere aut mori | |

| Borthwick | John Hugh Borthwick of that Ilk, 24th Lord Borthwick | Qui conducit | |

| Boyd | Alastair Ivor Gilbert Boyd, 7th Baron Kilmarnock | Confido | |

| Boyle | Patrick Robin Archibald Boyle, 10th Earl of Glasgow | Dominus providebit | |

| Brodie | Alexander Brodie of Brodie | Unite | |

| Bruce | Andrew Douglas Alexander Thomas Bruce, 11th Earl of Elgin | Fuimus | |

| Buchan | David Buchan of Auchmacoy | Non inferiora secutus | |

| Buchanan | Unknown | Clarior hinc Honos | |

| Burnett | James Burnett of Leys | Virescit vulnere virtus | |

| Cameron | Sir Donald Cameron of Lochiel | Aonaibh ri cheile | |

| Campbell | Torquhil Ian Campbell, 13th Duke of Argyll | Ne obliviscaris | |

| Carmichael | Richard Carmichael of Carmichael | Tout jour prest | |

| Carnegie | James George Alexander Bannerman Carnegie, 3rd Duke of Fife | Dred God | |

| Cathcart | Charles Alan Andrew Cathcart, 7th Earl Cathcart | I hope to speed | |

| Charteris | Francis David Charteris, 12th Earl of Wemyss and 8th Earl of March | This is our charter | |

| Clan Chattan | Kenneth MacKintosh of MacKintosh | Touch not the cat bot (without) a glove | |

| Chisholm | Andrew Francis Hamish Chisholm of Chisholm | Feros ferio | |

| Cochrane | Iain Alexander Douglas Blair Cochrane, 15th Earl of Dundonald | Virtute et labore | |

| Colquhoun | Sir Ivar Colquhoun of Luss, 8th Bt. | Si je puis | |

| Cranstoun | David Cranstoun of that Ilk and Corehouse | Thou shalt want ere I want | |

| Crichton | David Maitland Makgill Crichton of that Ilk | God send grace | |

| Cumming | Sir Alexander Gordon Cumming of Altyre, 7th Bt. | Courage | |

| Darroch | Duncan Darroch of Gourock | Be watchfull | |

| Davidson | Alister Davidson of Davidston | Sapienter si sincere | |

| Dewar | Michael Kenneth Dewar of that Ilk and Vogrie | Quid non pro patria | |

| Douglas | Unknown | Jamais arriere | |

| Drummond | John Eric Drummond, 18th Earl of Perth | Virtutem coronat honos | |

| Dunbar | Sir James Dunbar of Mochrum, 14th Bt. | In promptu | |

| Dundas | David Dundas of Dundas | Essayez | |

| Durie | Andrew Durie of Durie | Confido | |

| Eliott | Margaret Eliott of Redheugh | Fortiter et recte | |

| Erskine | James Thorne Erskine, 14th Earl of Mar and 16th Earl of Kellie | Je pense plus | |

| Farquharson | Alwyne Farquharson of Invercauld | Fide et fortitudine | |

| Fergusson | Sir Charles Fergusson of Kilkerran, 9th Bt. | Dulcius ex asperis | |

| Forbes | Nigel Ivan Forbes, 23rd Lord Forbes | Grace me guide | |

| Forsyth | Alistair Forsyth of that Ilk | Instaurator ruinae | |

| Fraser | Flora Marjory Fraser, Lady Saltoun (21st in line) | All my hope is in God | |

| Fraser of Lovat | Simon Fraser, 16th Lord Lovat | Je suis prest | |

| Gayre | Reinold Gayre of Gayre and Nigg | Super astra spero | |

| Gordon | Granville Charles Gomer Gordon, 13th Marquess of Huntly | Bydand | |

| Graham | James Graham, 8th Duke of Montrose | Ne oublie | |

| Grant | James Patrick Trevor Grant of Grant, 6th Baron Strathspey | Stand fast | |

| Grierson | Sir Michael Grierson of Lag, 12th Bt. | Hoc securior | |

| Gunn | Unknown | Aut pax aut bellum | |

| Haig | George Alexander Eugene Douglas Haig, 2nd Earl Haig | Tyde what may | |

| Haldane | Martin Haldane of Gleneagles | Suffer | |

| Hamilton | Angus Douglas Hamilton, 15th Duke of Hamilton | Through | Lowland & Highland |

| Hannay | Ramsey Hannay of Kirkdale and of that Ilk | Per ardua as alta | |

| Hay | Merlin Sereld Victor Gilbert Moncreiffe, 24th Earl of Erroll | Serva jugum | |

| Henderson | John Henderson of Fordell | Sola virtus nobilitat | |

| Hunter | Pauline Hunter of Hunterston | Cursum perficio | |

| Innes | Unknown | Be traist | |

| Irvine of Drum | David Charles Irvine of Drum | Sub sole sub umbra virens | |

| Jardine | Sir Alexander Jardine of Applegarth, 12th Bt. | Cave adsum | |

| Johnstone | Patrick Andrew Wentworth Johnstone of Annandale and of that Ilk, 11th Earl of Annandale and Hartfell | Nunquam non paratus | |

| Keith | James William Falconer Keith, 14th Earl of Kintore | Veritas vincit | |

| Kennedy | Archibald Angus Charles Kennedy, 8th Marquess of Ailsa | Avise la fin | |

| Kerr | Michael Andrew Foster Jude Kerr, 13th Marquess of Lothian | Sero sed serio | |

| Kincaid | Arabella Kincaid of Kincaid | This I'll defend | |

| Lamont | Peter N. Lamont of that Ilk | Ne parcas nec spernas | |

| Leask | Anne Leask of Leask | Virtute cresco | |

| Lennox | Edward J. H. Lennox of that Ilk and Woodhead | I'll defend | |

| Leslie | Ian Lionel Malcolm Leslie, 21st Earl of Rothes | Grip fast | |

| Lindsay | Robert Alexander Lindsay, 29th Earl of Crawford and 12th Earl of Balcarres | Endure fort | |

| Lockhart | Angus H. Lockhart of the Lee | Corda serrata pando | |

| Lumsden | Patrick Gillem Lumsden of that Ilk and Blanerne | Amor patitur moras | |

| MacAlester | William St J. S. MacAlester of Loup and Kennox | Fortiter | |

| McBain | James H. McBain of McBain | ||

| Malcolm (MacCallum) | Robin N. L. Malcolm of Poltalloch | In ardua petit | |

| Macdonald | Godfrey James Macdonald of Macdonald, 8th Baron Macdonald | Per mare per terras | |

| MacDonald of Clanranald | Ranald A. MacDonald of Clanranald | My hope is constant in thee | |

| MacDonald of Sleat | Sir Ian Bosville MacDonald of Sleat, 17th Bt. | Per mare per terras | |

| MacDonell of Glengarry | Aeneas Ranald MacDonnel of Glengarry | Creag an Fhitich | |

| MacDougall | Buaidh no bas | ||

| MacDowall | Fergus D. H. MacDowall of Garthland | Vincere vel mori | |

| MacFarlane | Unknown | This I'll Defend | |

| MacGillivray | Unknown | Touch Not This Cat | |

| MacGregor | Sir Malcolm Gregor MacGregor of MacGregor, 7th Bt. | 'S rioghal mo dhream | |

| MacIntyre | James W. MacIntyre of Glenoe | Per ardua | |

| MacKay | Hugh William Mackay, 14th Lord Reay | Manu forti | |

| MacKenzie | John Ruaridh Grant MacKenzie, 5th Earl of Cromartie | Luceo non uro | |

| MacKinnon | Anne MacKinnon of MacKinnon | Audentes fortuna juvat | |

| Mackintosh | John Lachaln Mackintosh of Mackintosh | Touch not the cat bot a glove | |

| MacLachlan | (Marjorie Maclachlan of Maclachlan) | Fortis et fidus | |

| MacLaren | Donald MacLaren of MacLaren and Achleskine | Creag an Turie | |

| Maclean | Hon Sir Lachlan Maclean of Duart and Morvern, 12th Bt. | Virtue mine honour | |

| MacLennan | Ruairidh MacLennan of MacLennan | Dum spiro spero | |

| MacLeod | John MacLeod of Macleod | Hold fast | |

| MacMillan | George MacMillan of Macmillan and Knap | Miseris succurrere disco | |

| Macnab | James Charles Macnab of Macnab | Timor omnis abesto | |

| Macnaghten | Sir Patrick Macnaghten of Macnaghten and Dundarave, 11th Bt. | I hope in God | |

| Macneacail | Ian Macneacail of Macneacail and Scorrybreac | Sgorr-a-bhreac | |

| MacNeil of Barra | Ian R. MacNeil of Barra | Vincere vel mori | |

| Macpherson | Sir William Macpherson of Cluny and Blairgowrie | Touch not a cat bot a glove | |

| MacRae | Unknown | Fortitudine | |

| MacThomas | Andrew P. C. MacThomas of Finegand | Deo juvante invidiam superabo | |

| Maitland | Patrick Francis Maitland, 17th Earl of Lauderdale | Consilio et animis | |

| Makgill | Ian Arthur Alexander Makgill, 14th Viscount of Oxfuird | Sine fine | |

| Mar | Margaret of Mar, Countess of Mar, 30th in line | Pans Plus | |

| Marjoribanks | Andrew George Marjoribanks of that Ilk | Et custos et pugnax | |

| Matheson | Sir Fergus John Matheson of Matheson, 7th Bt. | Fac et spera | |

| Menzies | David R.S. Menzies of Menzies | Vill God I Zall | |

| Moffat | Jean Moffat of that Ilk | Spero meliora | |

| Moncrieffe | Peregrine D.E.M. Moncrieffe of that Ilk | Sur esperance | |

| Montgomerie | Archibald George Montgomerie, 18th Earl of Eglinton and 6th Earl of Winton | Gardez bien | |

| Morrison | Iain M. Morrison of Ruchdi | Dun Eistein | |

| Munro | Hector W. Munro of Foulis | Dread God | |

| Murray | John Murray, 11th Duke of Atholl | Tout prest | |

| Nesbitt | Mark Nesbitt of that Ilk | I byd it | |

| Nicolson | David Henry Arthur Nicolson of that Ilk, 4th Baron Carnock | Generositate | |

| Ogilvy | David George Patrick Coke Ogilvy, 8th Earl of Airlie | A fin | |

| Ramsay | James Hubert Ramsay, 17th Earl of Dalhousie | Ora et labora | |

| Rattray | James S. Rattray of Craighall-Rattray | Super sidera votum | |

| Robertson | Alexander G. H. Robertson of Struan | Virtutis gloria merces | |

| Rollo | David Eric Howard Rollo, 14th Lord Rollo | La fortune passe partout | |

| Rose | Anna Elizabeth Guillemard Rose of Kilravock | Constant and true | |

| Ross | David Campbell Ross of Ross and Balnagowan | Spem successus alit | |

| Ruthven | Alexander Patrick Greysteil Ruthven, 2nd Earl of Gowrie | Deid schaw | |

| Scott | Walter Francis John Scott, 9th Duke of Buccleuch 11th Duke of Queensberry | Amo | |

| Scrymgeour | Alexander Henry Scrymgeour of Dundee, 12th Earl of Dundee | Dissipate | |

| Sempill | James William Stuart Whitmore Sempill, 21st Lord Sempill | Keep tryst | |

| Shaw | John Shaw of Tordarroch | Fide et fortitudine | |

| Sinclair | Malcolm Ian Sinclair, 20th Earl of Caithness | Commit thy work to God | |

| Skene | Danus Skene of Skene | Virtutis regia merces | |

| Stirling | Francis John Stirling of Cader | Gang forward | |

| Strange | Timothy Strange of Balcaskie | Dulce quod utile | |

| Sutherland | Elizabeth Millicent, Countess of Sutherland, 24th in line | Sans peur | |

| Swinton | John Walter Swinton of that Ilk | J'espere | |

| Trotter | Alexander Trotter of Mortonhall | In promptu | |

| Urquhart | Kenneth Trist Urquhart of Urquhart | Meane weil speak weil and doe weil | |

| Wallace | Ian Francis Wallace of that Ilk | Pro libertate | |

| Wedderburn of that Ilk | Henry David Wedderburn of that Ilk, Lord Scrymgeour, Master of Dundee | Non degener | |

| Wemyss | David Wemyss of that Ilk | Je pense |

Sources

- Clans and Tartans - Collins Pocket Reference, George Way of Plean and Romilly Squire, Harper Collins, Glasgow 1995 ISBN 0-00-470810-5

- MacBeth, High King of Scotland 1040 - 1057, Peter Beresford Ellis, Blackstaff Press Ltd. 3 Galway Park, Dundonald, Belfast BT16 0AN. 1990, ISBN 0-85640-448-9

- Scottish Clan & Family Encyclopedia, George Way of Plean and Romilly Squire, Barnes & Noble Books, New York 1998 ISBN 0-7607-1120-8

External links

- Clans, Families and Septs (http://www.electricscotland.com/webclans/clans_families_septs.htm)

- MyClan.com (http://www.myclan.com/): The Official Website of the Standing Council of Scottish Chiefs

- Balnagowan Castle: Use of the Ross badge without permission (http://www.greatclanross.org/balnagowan.html)

Links to alternative lists and maps

- Burke's Scotland — Scottish Clan Map (http://www.burkes-peerage.net/sites/scotland/sitepages/cmindex.asp) gives an key map linking to maps of areas of Scotland indicating many clans and their areas around the late 16th century, with links to information on the clans listed and a search field for other clans and families. Burke's Peerage & Gentry claims to be The authentic guide to the UK and Ireland's titled and untitled families.

- ScottishRadiance — A Map of the original Location of Scottish Clans (http://www.scottishradiance.com/clanmap.htm) provides an overview, including some Lowland clans/families.

- Electric Scotland guide to Scottish and Irish clans, families, tartans and history of the Gaels (http://www.electricscotland.com/webclans/index.html) links to a Map showing the districts of the highland clans of Scotland (http://www.electricscotland.com/webclans/clanmap.htm) (confined to the Highland area) and to their list of Official Scottish Clans and Families (http://www.electricscotland.com/webclans/clanmenu.htm) (with a comment from the Court of the Lord Lyon that "we would not normally use the word "official".).