Crater Lake National Park

|

|

| Crater Lake | |

|

Missing image LocMap_Crater_Lake_National_Park.png Image:LocMap_Crater_Lake_National_Park.png | |

| Designation | National Park |

| Location | Oregon USA |

| Nearest City | Eugene, Oregon |

| Coordinates | Template:Coor dm |

| Area | 183,224 acres 74,148 ha |

| Date of Establishment | May 22, 1902 |

| Visitation | 451,322 (2003) |

| Governing Body | National Park Service |

| IUCN category | II (National Park) |

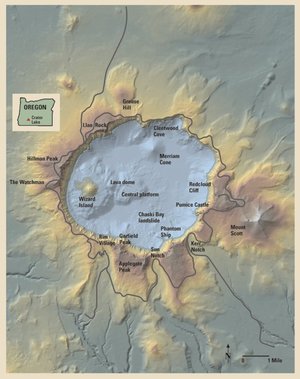

Crater Lake National Park is a U.S. National Park located in Oregon whose most famous feature is Crater Lake. The park encompasses the Crater Lake caldera, which rests in the remains of a destroyed volcano called Mount Mazama. The lake is 1958 feet (597 meters) deep at its deepest point, which makes it the deepest lake in the United States and the seventh deepest anywhere in the world. The caldera rim ranges in elevation from 7000 to 8000 feet (apx. 2130 to 2440 meters). The park covers 286 mi˛ (741 km˛).

Crater Lake has no streams flowing into or out of it. As a result, the water is extraordinarily clear, and the lake has a striking blue hue.

| Contents |

Geology

For detail, see Mount Mazama.

Volcanic activity in the area is fed by subduction off the coast of Oregon as the Juan de Fuca Plate slips below the North American Plate (see plate tectonics). Heat and compression generated by this movement has created a mountain chain topped by a series of volcanoes, which together are called the Cascade Range. The large volcanoes in the range are called the High Cascades. However, there are many other volcanoes in the range as well, most of which are much smaller.

About 400,000 years ago, Mount Mazama began life in much the same way as the other mountains of the High Cascades, as overlapping shield volcanoes. Over time, alternating layers of lava flows and pyroclastic flows built Mazama's overlapping cones until it reached about 11000 feet (~3550 meters) in height.

As the young stratovolcano grew, many smaller volcanoes and volcanic vents were built in the area of the park and just outside what are now the park's borders. Chief among these were cinder cones. Although the early examples are gone—cinder cones erode easily—there are at least 13 much younger cinder cones in the park, and at least another 11 or so outside its borders, that still retain their distinctive cinder cone appearance. There continues to be debate as to whether these minor volcanoes and vents were parasitic to Mazama's magma chamber and system or if they were related to background Oregon Cascade volcanism.

After a period of dormancy, Mazama became active again. Then, around 4860 BC, Mazama collapsed into itself during a tremendous volcanic eruption, losing 2500 to 3500 feet (760 to 1070 meters) in height. The eruption formed a large caldera that was later filled with a deep blue lake known today as Crater Lake.

The eruptive period that decapitated Mazama also laid waste to much of the greater Crater Lake area and deposited ash as far east as the northwest corner of what is now Yellowstone National Park, as far south as central Nevada, and as far north as southern British Columbia. It produced more than 150 times as much ash as the May 18, 1980 eruption of Mount St. Helens.

Park features

Some notable park features created by this huge eruption are:

- The Pumice Desert: A very thick layer of pumice and ash leading away from Mazama in a northerly direction. Even after thousands of years, this area is largely devoid of plants due to excessive porosity (meaning water drains through quickly) and poor soil composed primarily of regolith.

- The Pinnacles: When the very hot ash and pumice came to rest near the volcano, it formed 200 to 300 foot (60 to 90 meter) thick gas-charged deposits. For perhaps years afterward, hot gas moved to the surface and slowly cemented ash and pumice together in channels and escaped through fumaroles. Erosion later removed most of the surrounding loose ash and pumice, leaving tall pinnacles and spires.

Other park features:

- Mount Scott is a steep andesitic cone whose lava came from magma from Mazama's magma chamber; geologists call such volcano a 'parasitic' or 'satellite' cone. Volcanic eruptions apparently ceased on Scott sometime before the end of the Pleistocene; one remaining large cirque on Scott's northwest side was left unmodified by post-ice age volcanism.

- In the southwest corner of the park stands Union Peak, an extinct volcano whose primary remains consist of a large volcanic plug, which is lava that solidified in the volcano's neck.

- Crater Peak is a shield volcano primarily made of andesite and basalt lava flows topped by andesitic and dacite tephra.

- Timber Crater is a shield volcano located in the northeast corner of the park. Like Crater Peak, it is made of basaltic and andesitic lava flows, but, unlike Crater, it is topped by two cinder cones.

- Rim Drive is the most popular road in the park; it follows a scenic route around the caldera rim.

History

Crater-lake-reduced.jpg

The first known white man to visit the lake was a young prospector named John Wesley Hillman who, in 1853, stumbled upon it while looking for a lost mine. Stunned by his find, he named the indigo body of water "Deep Blue Lake" and the place on the southwest side of the rim where he first saw the lake later became known as Discovery Point. Hillman's suggested name later fell out of favor by locals, who preferred the name Crater Lake, although crater is a misnomer because the lake's basin is in fact a caldera, a volcanic feature that forms from subsidence, not from excavation.

Judge William Gladstone Steel led late 19th century efforts to have the greater Crater Lake area designated a national park. With the help of geologist Clarence Dutton, Steel organized a USGS expedition to study the lake in 1886. The team used pipe and piano wire to obtain depth soundings in different parts of the lake; their deepest sounding was very close to the modern official depth. At the same time, a topographer surveyed the area and created the first professional map of the Crater Lake area. Steel also helped name many features.

Partly based on data from the expedition and lobbying from Steel and others, Crater Lake National Park was established May 22, 1902.

Highways were later built to the park to help facilitate visitation. The 1929 edition of O Ranger! [1] (http://www.cr.nps.gov/history/online_books/albright3/) described access and facilities available by then:

- Crater Lake National Park is reached by train on the Southern Pacific Railroad lines into Medford and Klamath Falls, at which stops motor stages make the short trip to the park. A hotel on the rim of the lake offers accommodations. For the motorist, the visit to the park is a short side trip from the Pacific and Dalles-California highways. He will find, in addition to the hotel, campsites, stores, filling stations. The park is open to travel from late June or July 1 for as long as snow does not block the roads, generally until October.

Oregon_quarter,_reverse_side,_2005.jpg

Activities

There are many hiking trails inside the park, and several campgrounds. Fishing and swimming are allowed in the lake, and boat tours operate daily during the summer. Visitors can also take a boat to Wizard Island, a cinder cone inside the lake.

Observation points along the caldera rim are easily accessible by automobile via Rim Drive. The best vantage point, however, is from Mt. Scott (8926 feet, 2720.6 meters). Getting there requires a fairly steep 2.5 mile (4 km) hike from the Rim Drive trailhead. On a clear day from Mt. Scott's summit, a hiker can see for 100 miles (160 km) and can, in one single view, take in the entire caldera. Also visible from this point are the white-peaked High Cascade volcanoes to the north, the Columbia River Plateau to the east, and the Western Cascades to the west (with the more distant Klamath Mountains still further west).

In general, the best time to visit Crater Lake is during the summer months, as heavy snow in the park during the fall, winter, and spring forces the closure of roads and trails in the park, including popular Rim Drive (which is generally open from July to October).

References

- Fire Mountains of the West: The Cascade and Mono Lake Volcanoes, Stephen L. Harris, (Mountain Press Publishing Company, Missoula; 1988) ISBN 0-87842-220-X

- Geology of National Parks: Fifth Edition, Ann G. Harris, Esther Tuttle, Sherwood D., Tuttle (Iowa, Kendall/Hunt Publishing; 1997) ISBN 0-7872-5353-7

See also

External links

- Official site: Crater Lake National Park (http://www.nps.gov/crla/)

- NASA Earth Explorer page (http://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/Newsroom/NewImages/images.php3?img_id=10902)

- Crater Lake National Park (http://www.nationalparksgallery.com/parks/Crater-Lake-National-Park) - National Parks Gallery

- Photos of Crater Lake National Park - Terra Galleria (http://www.terragalleria.com/parks/np.crater-lake.html)

- Photographic virtual tour of Crater Lake National Park. (http://www.Untraveledroad.com/USA/Parks/CraterLake.htm)

- Guide to Crater Lake National Park on Compassmonkey.com (http://www.compassmonkey.com/places/locations.php/26)

- Google maps (http://www.google.com/maps?ll=42.940407,-122.119217&spn=0.163078,0.253372&t=k&hl=en)

Template:National parks of the United States

de:Crater-Lake-Nationalpark fr:Crater Lake pl:Park Narodowy Crater Lake