Bryce Canyon National Park

|

|

| Bryce Canyon | |

| |

| Designation | National Park |

| Location | Utah, United States |

| Nearest City | Tropic, Utah |

| Latitude | 37.628° N |

| Longitude | 112.167° W |

| Area | 35,835 acres 145 km² |

| Date of Establishment | June 8, 1923 (U.S. National Monument) September 15, 1928 (national park) |

| Visitation | 883,170 (2003) |

| Governing Body | National Park Service |

| IUCN category | II (National Park) |

Bryce Canyon National Park is a national park located in southwestern Utah in the United States. Contained within the park is Bryce Canyon. Despite its name, this is not actually a canyon, but rather a giant natural amphitheater created by erosion along the eastern side of the Paunsaugunt Plateau. Bryce is distinctive due to its unique geological structures, called hoodoos, formed from wind, water, and ice erosion of the river and lakebed sedimentary rocks. The red, orange and white colors of the rocks provide spectacular views.

Bryce is at a much higher elevation than nearby Zion National Park and the Grand Canyon. The rim at Bryce varies from 8,000 to 9,000 feet (2440 to 2740 m), whereas the south rim of the Grand Canyon sits at 7,000 feet (2130 m) above sea level. The area therefore has a very different ecology and climate, and thus offers a contrast for visitors to the region (who often visit all three parks in a single vacation).

The canyon area was settled by Mormon pioneers in the 1850s and was named after Ebenezer Bryce, who homesteaded in the area in 1875. The area around Bryce Canyon became a United States national monument in 1924 and was designated as a national park in 1928. The park covers 56 mi² (145 km²). The park receives relatively few visitors compared to Zion Canyon and the Grand Canyon, largely due to its remote location.

The national park also lends its name to Bryce, the 3D modelling software which specialises in rendering this kind of rugged landscape.

| Contents |

Geography

Bryce_Canyon_road_map.jpg

Bryce Canyon National Park is located in southern Utah about 50 miles (80 km) northeast and 1000 feet (300 meters) higher than Zion National Park. The weather in Bryce Canyon is therefore cooler and the park receives more precipitation. A nearby example very similar to Bryce Canyon but at a higher elevation is in Cedar Breaks National Monument.

The national park lies within the Colorado Plateau geographic province of North America and straddles the southeastern edge of the Paunsagunt Plateau west of the Paunsagunt Fault (Paunsagunt is Paiute for "home of the beaver"). Park visitors arrive from the plateau part of the park and look over the plateau's edge toward a valley containing the fault and the Paria River just beyond it (Paria is Paiute for "muddy or elk water"). The edge of the Kaiparowitz Plateau bounds the opposite side of the valley.

Bryce Canyon was not formed from erosion initiated from a central stream, meaning it technically is not a canyon. Instead headward erosion has excavated large amphitheater-shaped features in the Cenozoic-aged rocks of the Paunsagunt Plateau. This erosion exposed delicate and colorful pinnacles called hoodoos that are up to 200 feet (60 m) high. A series of amphitheaters extend more than 20 miles (30 km) within the park. The largest is 12 mile (19 km) long, 3 mile (4.8 km) wide and 800 foot (240 m) deep Bryce Amphitheater.

The highest part of the park, Rainbow Point, is at the end of this scenic drive. From there Aquarius Plateau, Bryce Amphitheater, Henry Mountains, the Vermilion Cliffs, and the White Cliffs can be seen.

Human history

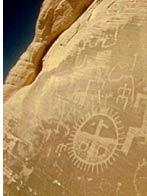

Native American habitation

Little is known about early human habitation in the Bryce Canyon area. Archaeological surveys of Bryce Canyon National Park and the Paunsaugunt Plateau show that people have been in the area for at least 10,000 years. Several thousand year old Basketmaker period Anasazi artifacts have been found south of the park. Other artifacts from the Pueblo period Anasazi and the Fremont culture (up to the mid 12th century) have also been found.

The Paiute Indians moved into the surrounding valleys and plateaus in the area around the same time that the other cultures left. These Native Americans hunted and gathered for most of their food but also supplemented their diet with some cultivated products. The Paiute in the area developed a mythology surrounding the hoodoos (pinnacles) in Bryce Canyon. They believed that hoodoos were the Legend People whom the trickster Coyote turned to stone. At least one older Paiute said his culture called the hoodoos Anka-ku-wass-a-wits, which is Paiute for "red painted faces".

White exploration and settlement

It was not until the late 18th and the early 19th century that the first Caucasians explored the remote and hard to reach area. Mormon scouts visited the area in the 1850s to gauge its potential for agricultural development, use for grazing, and settlement.

The first major scientific expedition to the area was led by U.S. Army Major John Wesley Powell in 1872. Powell, along with a team of mapmakers and geologists, surveyed the Sevier and Virgin River area as part of a larger survey of the Colorado Plateaus. His mapmakers kept many of the Paiute place names.

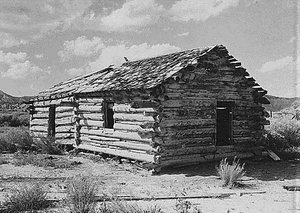

Small groups of Mormon pioneers followed and attempted to settle east of Bryce Canyon along the Paria River. In 1873 the Kanarra Cattle Company started to use the area for cattle grazing.

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints sent Scottish immigrant Ebenezer Bryce and his wife Mary to settle land in the Paria Valley because they thought Ebenezer's carpentry skills would be useful in the area. The Bryce family chose to live right below Bryce Canyon Amphitheater. Bryce grazed his cattle inside what are now park borders and reputedly thought that the amphitheaters were a "helluva place to lose a cow.". He also built a road to the plateau to retrieve firewood and timber and a canal to irrigate his crops and water his animals. Other settler's soon started to call the unusual place "Bryce's canyon", which was later formalized into Bryce Canyon.

A combination of drought, overgrazing, and flooding eventually drove the remaining Paiutes from the area and prompted the settlers to attempt construction of a water diversion channel from the Sevier River drainage. When that effort failed most of the settlers, including the Bryce family, left the area. Bryce moved his family to Arizona in 1880. The remaining settlers did manage to dig a 10 mile (16 km) long ditch from the Sevier's east fork into Tropic Valley.

Creation of the park

Bryce_Amphitheater.jpg

People like Forest Supervisor J.W. Humphrey promoted the scenic wonders of Bryce Canyon's amphitheaters and by 1918 nationally-distributed articles also helped to spark interest. However, poor access to the remote area and the lack of accommodations kept visitation to a bare minimum.

Ruby Syrett, Harold Bowman, and the Perry brothers later built modest lodging and set up "touring services" in the area. Syrett later served as the first postmaster of Bryce Canyon. Visitation steadily increased and by the early 1920s the Union Pacific Railroad became interested in expanding rail service into southwestern Utah to accommodate more tourists.

At the same time, conservationists became alarmed by the damage overgrazing and logging on the plateau along with unregulated visitation were having on the fragile features of Bryce Canyon. A movement to have the area protected was soon started and National Park Service Director Stephen Mather responded by proposing that Bryce Canyon be made into a state park. The governor of Utah and the Utah Legislature, however, lobbied for national protection of the area. Mather relented and sent his recommendation to President Warren G. Harding, who on June 8, 1923 declared Bryce Canyon National Monument into existence.

Bryce_Canyon_Lodge.jpg

A road was built the same year on the plateau to provide easy access to outlooks over the amphitheaters. From 1924 to 1925, Bryce Canyon Lodge was built from local timber and stone.

In 1924, members of U.S. Congress decided to start work on upgrading Bryce Canyon's protection status from a U.S. National Monument to a National Park to establish Utah National Park. A process of transferring ownership of private and state held land in the monument to the federal government started, the Utah Parks Company negotiating much of the transfer. The last of the land in the proposed park's borders was sold to the federal government four years later and on February 25, 1928 the renamed Bryce Canyon National Park was established.

Bryce_Canyon_visitors_center.jpg

In 1931, President Herbert Hoover annexed an adjoining area south of the park and in 1942, an additional 635 acres (257 hectares) were added. This brought the park's total area to the current figure of 35,835 acres (14502 hectares). Rim Road, the scenic drive that is still used today, was completed in 1934 by the Civilian Conservation Corps. Administration of the park was conducted from neighboring Zion Canyon National Park until 1956, when Bryce Canyon's first superintendent started work.

More recent history

The USS Bryce Canyon was named for the park and served as a supply and repair ship in the U.S. Pacific Fleet from March 7, 1947 to June 30, 1981. She was the only ship in the United States Navy to be decorated with the Gold E, having won five consecutive efficiency awards.

Responding to increased visitation and traffic congestion, the National Park Service implemented a voluntary summer-only in-park shuttle system in June 2000. In 2004, reconstruction began on the aging and inadequate road system in the park.

Geology

- Main article: Geology of the Bryce Canyon area

Natural_bridge_in_Bryce_Canyon.jpg

The Bryce Canyon area shows a record of deposition that spans from the last part of the Cretaceous period and the first half of the Cenozoic era. The ancient depositional environment of region around what is now the park varied:

- The Dakota Sandstone and the Tropic Shale were deposited in the warm shallow waters of the advancing and retreating Cretaceous Seaway (outcrops of these rocks are found just outside park borders).

- The colorful Claron Formation that the park's delicate hoodoos are carved from was laid down as sediments in a system of cool streams and lakes that existed from 63 to about 40 million years ago (from the Paleocene to the Eocene epochs). Different sediment types were laid down as the lakes deepened and became shallow and as the shoreline and river deltas migrated.

Several other formations were also created but were mostly eroded away following two major periods of uplift:

- The Laramide orogeny affected the entire western part of what would become North America starting about 70 million years ago and lasting for many millions of years after. This event helped to build the ancestral Rocky Mountains and in the process closed the Cretaceous Seaway. The Straight Cliffs, Wahweap, and Kaiparowits formations were victims of this uplift.

- The Colorado Plateaus were uplifted 10 to 15 million years ago and were segmented into different plateaus — each separated from its neighbors by faults and each having its own uplift rate. The Boat Mesa Conglomerate and the Sevier River Formation were removed following this uplift.

Vertical joints were created by this uplift, which were eventually (and still are) preferentially eroded. The easily eroded Pink Cliffs of the Claron Formation respond by forming free-standing pinnacles in badlands called hoodoos, while the more resistant White Cliffs formed monoliths. The pink color is from iron oxide and manganese. Also created were arches, natural bridges, walls, and windows. Hoodoos are composed of soft sedimentary rock, and are topped by a piece of harder, less easily-eroded stone that protects the column from the elements. Bryce Canyon has one of the highest concentrations of hoodoos of any place on Earth.

The formations exposed in the area of the park are part of the Grand Staircase. The oldest members of this supersequence of rock units are exposed in the Grand Canyon, the intermediate ones in Zion National Park, and its youngest parts are laid bare in Bryce Canyon area. A small amount of overlap occurs in and around each park.

Biology

Mule_Deer_in_Bryce_Canyon.jpg

The forests and meadows of Bryce Canyon provide the habitat to support diverse animal life, from birds and small mammals to foxes and occasional Bobcats, Mountain Lions, and Black Bears. Mule Deer are the most common large mammals in the park. Elk and Pronghorn Antelope, which have been reintroduced nearby, sometimes venture into the park. More than 160 species of birds visit the park each year, including swifts and swallows.

Most bird species migrate to warmer regions in winter, but jays, ravens, nuthatches, eagles, and owls stay. In winter, the Mule Deer, Mountain Lion, and coyotes will migrate to lower elevations. Ground squirrels and marmots pass the winter in hibernation.

There are there life zones in the park based on elevation:

- The lowest areas of the park are dominated by dwarf forests of pinyon pine and juniper with manzanita, serviceberry, and antelope bitterbrush in between. Aspen cottonwoods, Water birch, and willow grow in along streams.

- Ponderosa Pine forests cover the mid elevations with Blue Spruce and Douglas-fir in water-rich areas and manzanita and bitterbrush as underbrush.

- Douglas-fir and White Fir along with Aspen and Engelmann Spruce make up the forests on the Paunsaugunt Plateau. The harshest areas have Limber Pine and ancient Great Basin Bristlecone Pine holding on.

Also in the park are the black, lumpy, very slow-growing colonies of cryptobiotic soil, which are a mix of lichens, algae, fungi, and cyanobacteria. Together these organisms slow erosion, add nitrogen to soil and helps it to retain moisture.

While humans have greatly reduced the amount of habitat that is available to wildlife in most parts of the United States, the relative scarcity of water in southern Utah restricts human development and helps account for the region's greatly enhanced diversity of wildlife.

Activities

Most park visitors sightsee using the 18 mile (29 km) scenic drive, which provides access to 13 viewpoints over the amphitheaters.

Bryce Canyon has eight marked and maintained hiking trails that can be hiked in less than a day (round trip time, trailhead):

- Mossy Cave (One hour, Utah State Route 12 northwest of Tropic), Rim Trail (5–6 hours, anywhere on rim), Bristlecone Loop (One hour, Rainbow Point), and Queens Garden (1–2 hours, Sunrise Point) are easy to moderate hikes.

- Navajo Loop (1–2 hours, Sunset Point) and Tower Bridge (2–3 hours, north of Sunrise Point) are moderate hikes.

- Fairyland Loop (4–5 hours, Fairyland Point) and Peekaboo Loop (3–4 hours, Bryce Point) are strenuous hikes.

Several of these trails intersect, allowing hikers to combine routes for more challenging hikes.

The park also has two trails designated for overnight hiking; the 9-mile (14 km) long Riggs Loop Trail and the 23-mile (37 km) long Under the Rim Trail. Both require a backcountry camping permit. All told there are 50 miles (80 km) of trails in the park.

Horseriders_in_Bryce_Canyon-NPS_photo.jpg

More than 10 miles (16 km) of marked but ungroomed skiing trails are available off of Fairyland, Paria, and Rim trails in the park. Twenty miles of connecting groomed ski trails are in nearby Dixie National Forrest and Ruby's Inn.

The air in the area is so clear that on most days from Yovimpa and Rainbow points, Navajo Mountain and the Kaibab Plateau can be seen 90 miles (140 km) away in Arizona. On a really clear day the 200 mile (320 km) distant Black Mesas of eastern Arizona and western New Mexico can be seen. The park also has a 7.3 magnitude night sky, making it the one of the darkest in North America. Stargazers can therefore see 7500 stars with the naked eye, while in most places fewer than 2000 can be seen due to light pollution (in many large cities only a few dozen can be seen).

There are two campgrounds in the park, North Campground and Sunset Campground. Loop A in North Campground is open year-round. Additional loops and Sunset Campground are open from late spring to early autumn. The 114-room Bryce Canyon Lodge is another way to overnight in the park.

References

- Geology of National Parks: Fifth Edition, Ann G. Harris, Esther Tuttle, Sherwood D., Tuttle (Iowa, Kendall/Hunt Publishing; 1997) ISBN 0-7872-5353-7

- Secrets in The Grand Canyon, Zion and Bryce Canyon National Parks: Third Edition, Lorraine Salem Tufts (North Palm Beach, Florida; National Photographic Collections; 1998) ISBN 0-9620255-3-4

- The Hoodoo, National Park Service, Fall, Winter, Spring 2003–2004 edition

- Bryce Canyon visitors guide, National Park Service (some public domain text in the biology section)

- American Park Network: Bryce Canyon (http://www.americanparknetwork.com/parkinfo/bc/index.html) — Flora and Fauna (http://www.americanparknetwork.com/parkinfo/bc/flora/index.html), Preservation (http://www.americanparknetwork.com/parkinfo/bc/pres/index.html)

Further reading

- DeCourten, Frank. 1994. Shadows of Time, the Geology of Bryce Canyon National Park. Bryce Canyon Natural History Association.

- Kiver, Eugene P., Harris, David V. 1999. Geology of U.S. Parklands 5th ed. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- Sprinkel, Douglas A., Chidsey, Thomas C. Jr., Anderson, Paul B. 2000. Geology of Utah's Parks and Monuments. Publishers Press.

External links

- Brycecanyontour.com (2004). Bryce Canyon Travel Guide (http://www.brycecanyontour.com/). Retrieved February 13, 2005.

- National Park Service (2005). Bryce Canyon National Park (http://www.nps.gov/brca/). US Department of the Interior. Retrieved February 13, 2005.

- Breaking The Gigapixel Barrier (2003). Gigapixel Images (http://www.tawbaware.com/maxlyons/gigapixel.htm). Retrieved March 6, 2005.

Template:National parks of the United Statesde:Bryce-Canyon-Nationalpark fr:Bryce Canyon ko:브라이스캐니언 국립공원 pl:Park Narodowy Bryce Canyon