Battle of Warsaw (1920)

|

|

The Battle of Warsaw (sometimes referred to as the Miracle at the Vistula, Polish Cud nad Wisłą) was the decisive battle of the Polish-Bolshevik War (also known as the Polish-Soviet War), the war that began soon after the end of World War I in 1918 and lasted until the Treaty of Riga in 1921.

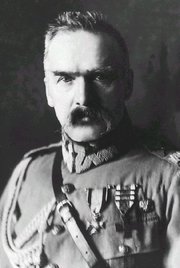

The Battle of Warsaw was fought between 13 and 25 August, 1920, as Red Army forces commanded by Mikhail Tukhachevski approached the Polish capital of Warsaw and the nearby Modlin Fortress. On August 16 Polish forces commanded by Józef Piłsudski counter-attacked from the south, forcing the Russian forces into a disorganised withdrawal east, behind the Niemen River. Estimated Bolshevik losses were 10,000 killed, 500 missing and 10,000 wounded and 66,000 taken prisoner, compared to Polish losses of approximately 4,500 killed, 10,000 missing and 22,000 wounded.

Before the Miracle at the Vistula, both the Bolsheviks and the majority of foreign experts considered Poland to be on the verge of defeat. The stunning and unexpected Polish victory in the Battle of Warsaw crippled the Bolshevik forces. Over the coming months, several more Polish victories would secure Polish independence and eastern borders.

| Contents [hide] |

The battle

Prelude to the battle

Poles were fighting to preserve their newly regained independence, lost in 1795 after the partitions of Poland, and to carve out the borders of the new country (Miedzymorze federation) from the territory of their former partitioners, Russia, Germany and Austro-Hungary.

The Bolsheviks had gained an upper hand in the Russian Civil War in 1919, dealing crippling blows to their opponents, the White Russians. Vladimir Lenin viewed Poland as the bridge that had to be crossed so that communist ideals could be brought to the Central and Western Europe, and the Polish-Bolshevik War seemed like a perfect way to test the Bolsheviks strength. Revolutionary speeches stated that the revolution was to be carried out on the bayonets of the Soviet "soldats" to Western Europe and that the shortest route to Berlin and Paris led through Warsaw. After early setbacks against Poland in 1919, the Bolshevik offensive that began in early 1920 had been overwhelmingly successful and by mid-1920, the entire world expected Poland to collapse at any moment. The Soviet strategy called for a massed push toward the Polish capital, Warsaw. The capture of Warsaw would have had a tremendous propaganda effect for the Soviets, who expected this not only to undermine the morale of the Poles but to start a series of international communist uprisings, and clear the path for the Red Army to join the German Revolution.

Polish-soviet_war_1920_Polish_defences_near_Milosna,_August.jpg

The Soviet 1st Cavalry Army under Semyon Budyonny broke through Polish lines in mid-June 1920. This led to a collapse of all Polish fronts in the east. On July 4, 1920, Mikhail Tukhachevski's Western Front began an all-out assault in Belarus from the Berezina River, forcing Polish forces into retreat. On July 19 the Red Army seized Grodno, on July 28 reached Białystok, and three days later captured the Brześć fortress. The withdrawal of Polish forces from the north-eastern front was rather disorganised.

The battle plan

Polish plan

By the beginning of August the Polish retreat had become more organized. At first Józef Piłsudski wanted to base his operation on the Bug River and Brest-Litovsk, but the unexpected fall of these two barriers made it impossible. On the night of August 5-August 6 Pilsudski at the Belweder Palace in Warsaw conceived a revised plan of action. This new plan called for the Polish forces to withdraw across the Vistula River and defend the bridgeheads in Warsaw and the Wieprz River. Some 25% of the available divisions would be concentrated to the south for a strategic counter-offensive.

Next, Piłsudski's plan required that the 1st and 2nd Army of Gen. Józef Haller's Central Front (10 1/2 divisions) take a passive role, facing the Soviet frontal attack on Warsaw from the east, keeping their entrenched positions at any cost. At the same time the 5th Army (5 1/2 divisions) under Gen. Władysław Sikorski, subordinate to gen. Haller, would defend the northern area near the Modlin fortress and when possible strike from behind Warsaw, thus cutting off the Soviet forces attempting to envelope Warsaw from that direction, and break through the enemy front and fall on the rear of the Soviet Northwestern Front. An additional 5 divisions in the 5th Army were defending Warsaw from the north. 1st Army if general Franciszek Latinik would defend the city of Warsaw itself and 2 Army of general Bolesław Roja was assigned to defend the Vistula river line from Góra Kalwaria to Dęblin. The most important role, however, was assigned to a relatively small (~20 000), newly assembled Reserve Army (known also as Assault Group - Grupa Uderzeniowa), commanded personally by Józef Piłsudski, composed of the most battle-hardened and determined Polish units shuffled from the southern front, strengthened by the 4th Army of general Leonard Skierski and 3rd Army of general Zygmunt Zieliński, which after retreating from the Western Bug river area moved not directly towards Warsaw but crossed the Wieprz river and broke off contact with the Soviet pursuers. Their task was to spearhead a lightning northern offensive, from the Vistula-Wieprz river triangle south of Warsaw, through a weak spot identified by Polish intelligence between the Soviet Western and Southwestern Fronts. That offensive would separate the Soviet Western Front from its reserves and disorganize its movements. Eventually the gap between Gen. Sikorski's 5th Army and the advancing Reserve Army would close near the East Prussian border and destroy the Soviet offensive, "trapped in a sack."

Although based on fairly reliable information provided by Polish intelligence and intercepted Soviet radio communications, the plan was labelled as 'amateurish' by many high-ranking army officers and military experts, who were quick to point out Piłsudski's lack of formal military education. Many Polish units, a mere week before the planned date of the counter-attack, were fighting in places as far as 100-150 miles from the concentration points. All of the movements of the troops were done within striking distance of the Red Army. One strong push by the Red Army could derail plans for a Polish counter-attack and endanger the cohesion of the whole Polish front. Piłsudski's plan was strongly criticized by Polish commanders and officers of the French Military Mission, and even Piłsudski himself in his memoires admitted that this was a very risky gamble and the reasons he decided to go forward with the plan were the defeatist mood of politicians, fear for the safety of the capital and the prevailing feeling that if Warsaw was to fall, all was lost. Only the desperate situation of the Polish forces persuaded other army commanders to go along with it, as they realized that under such circumstances it was the only possible solution to avoid a devastating defeat. Coincidentally, when a copy of the plan "accidentally" fell into Soviet hands it was considered to be a poor deception attempt and ignored. A few days later the Soviets paid dearly for this mistake.

Tukhachevsky-mikhail.jpg

Bolshevik plan

Mikhail Tukhachevski planned to encircle and surround Warsaw by crossing the Vistula river, near Włocławek, to the north and south of the city and launch an attack from the north-west. With his 24 divisions he planned to repeat the classic maneuvre of Ivan Paskievich, who in 1831, during the November Uprising, had crossed the Vistula at Toruń and reached Warsaw practically unopposed. This move would also cut the Polish forces off from Gdańsk, the only port open to shipments of arms and supplies.

The main weakness of the Soviet plan was the weak southern flank, secured only by the Pinsk Marshes and weak Mozyr Group, and the majority of Soviet Southwest Front were engaged in the battle of Lwów.

First phase, August 12

Meanwhile Bolsheviks pushed forward. Gay Dimitrievich Gay Cavarly Corps together with the 4th Army crossed Wkra river and advanced towards the town of Włocławek. 15th and 3rd Army were approaching Modlin fortress and 16th Army moved directly towards Warsaw.

The final Soviet assault on Warsaw began on August 12 with the Soviet 16th Army the attack at the town of Radzymin (only 23 km east of Warsaw), and its initial success prompted Piłsudski to speed up the execution of his defense plan by 24 hours.

Battle_of_Warsaw_-_Phase_1.png

The first phase of the battle started August 13 with a Red Army frontal assault on the Praga bridgehead. In heavy fighting, Radzymin changed hands several times and foreign diplomats with the exception of British and Vatican ambassadors, hastily left Warsaw. On August 14 it fell to the Red Army, and the lines of Gen. Władysław Sikorski's Polish 5th Army were broken. The 5th Army had to fight three Soviet armies at once: the 3rd, 4th and 15th. The Modlin sector was reinforced with reserves (the Siberian Brigade, and Gen. Franciszek Krajowski's fresh 18th Infantry Division--both, elite, battle-tested units), and the 5th Army held out till dawn.

The situation was saved around midnight when the 203rd Uhlan Regiment managed to break through the Bolshevik lines and destroy the radio station of Dimitriy Shuvayev's Soviet 4th Army. The latter thus lost contact with its headquarters and continued marching toward Toruń and Płock, unaware of Tukhachevski's order to turn south. The raid by the 203rd Uhlans is sometimes referred to as the Miracle of Ciechanów.

At the same time, the Polish 1st Army under Gen. Franciszek Latinik resisted a Red Army direct assault on Warsaw by six rifle divisions. The struggle for control of Radzymin forced Gen. Józef Haller, commander of the Polish Northern Front, to start the 5th Army's counterattack earlier than planned.

During this time, behind the front lines, Pilsudski was finishing his plans for the counter-offensive. Pilsudski decided to personally supervise the attack and because of the enormous risks involved, understanding the danger of combat, before departing for the front he handed a letter with his resignation from all state functions which he held. Thereafter, between August 13 and 15, he visited all the units of the 4th Army concentrating near Puławy, about 100km south of Warsaw. He tried to raise the morale of the units, since many soldiers were tired and demoralized and numerous recently incorporated replacements showed everyone the extent of the losses the Polish forces had endured during the recent retreats. Logistics were a nightmare, as the Polish army was supported by guns made in five countries and used rifles manufactured in six different countries, each of them needing different ammunition. Adding to the problem was the acknowledged fact that the equipment was in poor shape. Pilsudski remembers: "In 21 Division almost half of the soldiers paraded in front of me barefoot." Nevertheless in only three days Pilsudski was able to raise the morale of his troops and motivate them for one of their greatest efforts. Within a short period of time the spirits of the troops changed from a very low morale to full confidence in absolute victory.

Second phase, August 14

The 27th Infantry Division of the Red Army managed to get to the village of Izabelin 8 miles from the capital of Poland, but this was the closest that Russian forces would come to Warsaw. Soon the tides of battle would change.

Tukhachevski, certain that all was going according to his plan, was actually falling into Piłsudski's trap. The Russian march across the Vistula in the north was striking into an operational vacuum as there was no sizeable group of Polish troops in that area. On the other hand, south from Warsaw, where the fate of the war was about to be decided, Tukhachevski left only token forces to guard the vital link between North-Western and South-Western Fronts. Mozyr Group, which was to fulfil this task, numbered only 8 thousand soldiers. Another error committed by the Soviet generals, which influenced the outcome of the war, neutralized the 1st Cavalry Army of Semyon Budyonny, a unit much feared by Piłsudski and other Polish commanders. Soviet High Command, at Tukhachevski's insistence, ordered the 1st Cavalry Army to march toward Warsaw from the south. Semyon Budyonny did not obey this order due to a grudge between commanding South-Western Front generals Aleksandr Yegorov and Tukhachevski. In addition, the political games of Joseph Stalin who was at the time chief political commissar of the South-Western Front, further contributed to Yegorov's and Budyonny's disobedience. Joseph Stalin, in search of personal triumph, desired to capture the important industrial center of Lwów, besieged by Bolshevik forces but still resisting their assaults. Ultimately Budyonny's forces, which could have changed the course of the history, marched on Lwow instead of Warsaw and excluded themselves from the battle.

Battle_of_Warsaw_-_Phase_2.png

The Polish 5th Army counter-attacked August 14, crossing the Wkra River. It faced the combined forces of the Soviet 3rd and 15th Armies (both numerically and technically superior). The struggle at Nasielsk lasted until August 15 and resulted in an almost complete destruction of the town. However, the Soviet advance toward Warsaw and Modlin was halted at the end of August 15th and on that day Polish forces recaptured Radzymin, which boosted the Polish morale.

From that moment on Gen. Sikorski's 5th Army's progress was extremely successful, pushing exhausted Soviet units away from Warsaw which resulted in an almost blitzkrieg-like operation. Sikorski's units, supported by the majority of the small number of Polish tanks, armoured cars and artillery of the two armoured trains, advanced at the speed of thirty kilometres a day, soon destroying any Soviet hopes for completing their "enveloping" manoeuvre in the north.

Third phase, August 16

On August 16, the Polish Reserve Army commanded by Józef Piłsudski began its march north from the Wieprz River. It faced the Mozyr Group, a Soviet corps that had defeated the Poles during the Kyiv operation several months earlier. However, during its pursuit of the retreating Polish armies, the Mozyr Group had lost most of its forces and been reduced to a mere two divisions covering a 150-kilometre front-line on the left flank of the Soviet 16th Army. On the first day of the counter-offensive, only one of the five Polish divisions reported any sort of opposition, while the remaining four, supported by a cavalry brigade, managed to push north 45 kilometres, unopposed. When evening fell the town of Włodawa had been liberated, and the communication and supply lines of the Soviet 16th Army had been cut. Even Piłsudski was surprised by these early successes, when the Reserve Army units covered about seventy kilometres in 36 hours splitting the Soviet offensive and meeting virtually no resistance. It turned out that the Mozyr Group consisted solely of the 57th Infantry Division which had been beaten in the first day of the operation. Consequently executing Piłsudski's plan, Polish armies found a huge gap between the Russian fronts and exploited it, continuing their northward offensive with two armies following and wiping out the surprised and confused enemy.

On August 18 Mikhail Tukhachevski, in his headquarters in Minsk some 300 miles east from Warsaw, became fully aware of the extent of his defeat and ordered remnants of his forces to retreat and regroup. His intention was to straighten the front line, stop the Polish attack and to regain the initiative, but the orders either arrived too late or failed to arrive at all. Soviet General Gay's 3rd Cavalry Corps continued to advance toward Pomerania, its lines endangered by the Polish 5th Army, which had finally managed to push back the Bolshevik armies and gone over in pursuit. The Polish 1st Division of the Legion, in order to cut the enemy's retreat, did a remarkable march from Lubartow to Bialystok - 163 miles in 6 days. The soldiers fought in two battles, slept only a few hours and marched for up to 21 hours a day. Their sacrifice and endurance was rewarded by cutting off the entire 16th Soviet Army at Bialystok and taking most of its troops prisoner.

The Soviet armies in the center of the front fell into chaos. Some divisions continued to fight their way toward Warsaw, while others turned to retreat, lost their cohesion and panicked. The Russian commander-in-chief lost contact with most of his forces, and all the Soviet plans were thrown into disorder by the loss of contact. Only the Russian 15th Army remained an organised force and tried to obey Tukhachevski's orders, shielding the withdrawal of the most western extended 4th Army. But it was defeated twice on August 19th and 20th and it joined the general rout of the Red Army's North-Western Front. Tukhachevski had no choice but to order a full retreat toward the Western Bug River. By August 21st all organized resistance ceased to exist and by August 31 the Soviet South-Western Front was completely routed.

Aftermath

Although Poland managed to achieve victory and push back the Russians, Piłsudski's plan to outmanoeuvre and surround the Red Army did not succeed completely. Four Soviet armies began to march toward Warsaw on July 4th in the framework of the North-Western Front. By the end of August the 4th and 15th Armies were defeated in the field, their remnants crossed the Prussian border and were disarmed. Nevertheless, these troops were soon released and fought against Poland again. The 3rd Army retreated east so quickly that Polish troops could not catch up with them; consequently, this army sustained the least amount of losses. The 16th Army disintegrated at Bialystok and most of its soldiers became prisoners of war. Majority of the Gay's 3rd Cavalry Corps would be forced to cross the German border and be interned in East Prussia.

Polish-soviet_war_1920_Aftermath_of_Battle_of_Warsaw.jpg

Soviet losses were about 10,000 dead, 500 missing, 10,000 wounded and 65,000 captured (compared to Polish losses of approximately 4,500 killed, 22,000 wounded and 10,000 missing). Between 25,000 and 30,000 Soviet troops managed to reach the borders of Germany. After crossing into East Prussia, they were briefly interned, then allowed to leave with arms and equipment. Poland captured about 231 artillery guns and 1,023 machine-guns.

The southern arm of the Red Army's forces had been routed and no longer posed a threat to the Poles. Semyon Budyonny's 1st Cavalry Army besieging Lwów had been defeated at the Battle of Komarów (August 31, 1920) and the Battle of Hrubieszów. By mid-October, the Polish Army had reached the Tarnopol-Dubno-Minsk-Drisa line.

Tukhachevski managed to reorganize the eastward-retreating forces and in September established a new defensive line near Grodno. In order to break it, the Polish Army had to fight the Battle of the Niemen River (September 15-September 21), once again defeating the Bolshevik armies. After the Battle of the Szczara River both sides were exhausted by war and on October 12, under heavy pressure from France and Britain, a cease-fire was signed. By October 18 the fighting was over, and on March 18, 1921, the Treaty of Riga was signed, ending hostilities.

Soviet propaganda before the Battle of Warsaw had described the fall of Poland's capital as imminent, and the anticipated fall of Warsaw was to be a signal for the start of a large-scale communist revolution in Poland, Germany and other European countries, economically devastated from the First World War. The Soviet defeat at Warsaw was thus a setback for some Soviet officials (including Vladimir Lenin) who wished to promote a communist revolution by force of arms in the aftermath of the First World War.

Orders of battle

Polish

Powazki_1920.JPG

3 Fronts (Northern, Central, Southern), 7 Armies, a total of 32 divisions: 46,000 infantry; 2,000 cavalry; 730 machine guns; 192 artillery batteries; and several units of (mostly FT-17) tanks.

| Northern Front Haller | Central Front Rydz-Śmigły | Southern Front Iwaszkiewicz |

|---|---|---|

| 5th Army Sikorski | 4th Army Skierski | 6th Army Jędrzejewski |

| 1st Army Latinik | 3rd Army Zieliński | Ukrainian Army Petlura |

| 2nd Army Roja |

Fronts:

- Northern Front: 250 km., from East Prussia, along the Vistula River, to Modlin:

- Central Front:

- Southern Front - between Brody and the Dniestr River

Soviet

| North-Western Front Tukhachevskiy |

|---|

| 4th Army Shuvayev |

| 3rd Cavalry Corps Gay |

| 15th Army Kork |

| 3rd Army Lazarievich |

| 16th Army Sollohub |

| Cavalry Army Budyonny |

See also

Notes

- Soviet casualties refer to all the Warsaw-related operations, from the fighting on the approaches to Warsaw, through the counteroffensive, to the battles of Białystok and Osowiec, while the estimate of Bolshevik strength may be only for the units that were close to Warsaw, not counting the units held in reserve that took part in the later battles.

References

- Edgar Vincent D'Abernon, The eighteenth decisive battle of the world: Warsaw, 1920, Hyperion Press, 1977, ISBN 0883554291.

- Norman Davies, White Eagle, Red Star: The Polish-Soviet War, 1919-20, Pimlico, 2003, ISBN 0712606947.

- J.F.C. Fuller, The Decisive Battles of the Western World, Hunter Publishing, ISBN 0586080368.

- Jeremy Keenan, The Pole: The Heroic Life of Jozef Pilsudski, Gerald Duckworth & Co. Ltd, 2004, ISBN 0715632108.

- Richard M. Watt, Bitter Glory: Poland and Its Fate, 1918-1939, Hippocrene Books, 1998, ISBN 0781806739.

- M. Tarczyński, Cud nad Wisłą, Warszawa, 1990.

- Józef Piłsudski, Pisma zbiorowe, Warszawa, 1937, reprinted by Krajowa Agencja Wydawnicza, 1991, ISBN 8303030590.

- Mikhail Tukhachevski, Lectures at Military Academy in Moscow, February 7-10, 1923, reprinted in Pochód za Wisłę, Łódź, 1989.

External links

- Battle Of Warsaw 1920 by Witold Lawrynowicz; A detailed write-up, with bibliography (http://www.hetmanusa.org/engarticle1.html)

- 3 scans Polish maps (http://www.geocities.com/hallersarmy/maps.html)