Arabic alphabet

|

|

Template:Alphabet The Arabic alphabet is the script used for writing the Arabic language. Because the Qur'an, the holy book of Islam, is written with this alphabet, its influence spread with that of Islam and it has been, and still is, used to write many other languages from families unrelated to the Semitic languages, such as Persian and Urdu. (See fuller list below.)

In order to accommodate the phonetics of other languages, the alphabet has been adapted by the addition of letters and other symbols. The alphabet presents itself in different styles such as Nasta'līq, Thulthī, Kūfī and others (see Arabic calligraphy), just like different fonts for the Roman alphabet. Superficially, these styles appear quite different, but the basic letterforms remain the same.

| Contents |

Structure of the Arabic alphabet

The Arabic alphabet is written from right to left and is composed of 28 basic letters. Adaptations of the script for other languages such as Persian and Urdu have additional letters. There is no difference between written and printed letters; the writing is unicase (i.e. the concept of upper and lower case letters does not exist). On the other hand, most of the letters are attached to one another, even when printed, and their appearance changes as a function of whether they connect to preceding or following letters. Some combinations of letters form special ligatures.

The Arabic alphabet is an "impure" abjad - since short vowels are not written, though long ones are - so the reader must know the language in order to restore the vowels. However, in editions of the Qurʼan or in didactic works a vocalization notation in the form of diacritic marks is used. Moreover, in vocalized texts, there is a series of other diacritics of which the most modern are an indication of vowel omission (sukūn) and the lengthening of consonants (šadda).

The names of Arabic letters can be thought of as abstractions of an older version where the names of the letters signified meaningful words in the Proto-Semitic language.

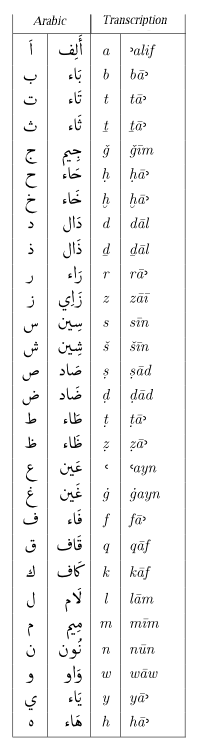

There are two orders for Arabic letters in the alphabet, the original Abjadī أبجدي order matches the ordering of letters in all alphabets derived from the Phoenician alphabet, including the English ABC. The other order featured in the table above is the Hejā'ī هجائي order where letters are grouped according to their shape proximity to each adjacent letters' shapes.

Presentation of the alphabet

There are at least a half dozen "standards" for transliterating Arabic characters, each with its own flaws. None of them works as well as the Arabic alphabet, but the basic idea is to make text accessible to people who do not know the Arabic alphabet.

The following table provides all of the Unicode characters for Arabic, and none of the supplementary letters used for other languages. Current browser technology still has not caught up, so some of forms may not display correctly. The table also shows some of the many Latin-alphabet characters that have been used in the past. For a more exhaustive treatment, see SATTS (Standard Arabic Technical Transliteration System), a U.S. military standard, and the links on the DIN-31635 page.

To complicate the entire question still further, there are regional differences in the way Arabic speakers pronounce the various letters. This chart only attempts to set forth the "standard" pronunciation as taught in universities. The phonetic equivalents are given in the Continental version of the International Phonetic Alphabet. For more details concerning the pronunciation of Arabic, consult the article on Arabic pronunciation.

Primary letters

Letters lacking an initial or medial version are never tied to the following letter, even within a word. As to ﺀ hamza, it has only a single graphic, since it is never tied to a preceding or following letter. However, it is sometimes 'seated' on a waw, ya or alif, and in that case the seat behaves like an ordinary waw, ya or alif.

This chart does not contain an exhaustive list of all the variant transliterations that European orientalists have invented. There are also numerous local variations on pronunciation, even when speaking the standard, literary language (Fusha).

The transliterations that use digits are commonly used by Arabs online, e.g., in chat rooms, where both Arabic script and the Roman characters with diacritics are unavailable. The numbers used bear a vague resemblance to the Arabic characters.

Other letters

The following are not actual letters, but rather different orthographical shapes for letters, and in the case of the lām ʼalif, a ligature.

| Stand-alone | Initial | Medial | Final | Name | Trans. | Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ﺁ | — | ﺂ | Template:Unicode | Template:Unicode | ||

| ﺓ | — | ﺔ | Template:Unicode | Template:Unicode | , | |

| ﻯ | — | ﻰ | Template:Unicode | Template:Unicode | ||

| ﻻ | — | ﻼ | Template:Unicode | Template:Unicode | ||

Notes

The Template:Unicode, commonly using Unicode 0x0649 (ى) in Arabic, is sometimes replaced in Persian or Urdu, with Unicode 0x06CC (ی), called "Farsi Yeh". This is appropriate to its pronunciation in those languages. The glyphs are identical in isolated and final form (ﻯ ﻰ), but not in initial and medial form, in which the Farsi Yeh gains two dots below (ﯾ ﯿ) while the Template:Unicode has neither an initial nor a medial form.

Writing the hamza

Initially, the letter Template:Unicode indicated an occlusive glottal, or glottal stop, transcribed by , confirming the alphabet came from the same Phoenician origin. Now it is used in the same manner as in other abjads, with Template:Unicode and Template:Unicode, as a mater lectionis, that is to say, a consonant standing in for a long vowel (see below). In fact, over the course of time its original consonantal value has been obscured, since Template:Unicode now serves either as a long vowel or as graphic support for certain diacritics (madda or hamza).

The Arabic alphabet now uses the hamza to indicate a glottal stop, which can appear anywhere in a word. This letter, however, does not function like the others: it can be written alone or on a support in which case it becomes a diacritic:

- alone: ء ;

- with a support: إ, أ (above and under a Template:Unicode), ؤ (above a Template:Unicode), ئ (above a Template:Unicode without points or Template:Unicode).

The details of writing of the hamza are discussed below, after that of the vowels and syllable-division marks, because their functions are related.

Ligatures

The only compulsory ligature is lām+'alif. All other ligatures (yaa - mīm, etc.) are optional.

Some fonts include a Salla-llahu 'alayhi wasallam glyph:

Muslims normally use this phrase after any mention of the prophet Muhammad.

Fonts also include a special glyph for the word "li-llah", which means "to God."

Combined with the letter 'alif, it becomes Allah:

The latter is a work-around for the shortcomings of most text processors, which are incapable of displaying the correct vowel marks for the word "Allah". Compare the display below, which depends on your browser and installed fonts:

- للّٰه

Alternatively, some fonts may be designed to replace the sequence lam-lam-heh or alif-lam-lam-heh to the ligature U+FDF2 ARABIC LIGATURE ALLAH ISOLATED FORM, but this seems to depends on the font, with Arial, Bitstream Cyberbit and Times New Roman, as examples of the former, and Arial Unicode MS as an example of the latter. This is probably because some font designers interpret U+FDF2 as "li-llah", and others as "Allah" and so design the glyph and replacement mapping as such.

lam-lam-heh:

alif-lam-lam-heh:

U+FDF2:

Diacritics

Vowels

Arabic short vowels are generally not written, except sometimes in sacred texts (such as the Qurʼan) and didactics, which are known as vocalised texts. Occasionally short vowels are marked where the word would otherwise be ambiguous and cannot be resolved simply from context.

Short vowels may be written with diacritics placed above or below the consonant that precedes them in the syllable. (All Arabic vowels, long and short, follow a consonant; contrary to appearances: there is a consonant at the start of a name like Ali — in Arabic Template:Unicode — or a word like Template:Unicode.)

Long "a" following a consonant other than hamzah is written with a short-"a" mark on the consonant plus an alif after it (Template:Unicode). Long "i" is a mark for short "i" plus a yaa yāʼ, and long u is mark for short u plus waaw, so aā = ā, iy = ī and uw = ū);

Long "a" following a hamzah sound may be represented by an alif-madda or by a floating hamzah followed by an alif.

In an un-vocalised text (one in which the short vowels are not marked), the long vowels are represented by the consonant in question (alif, yaa, waaw). Long vowels written in the middle of a word are treated like consonants taking sukūn (see below) in a text that has full diacritics.

For clarity, vowels will be placed above or below the letter د dāl so it is necessary to read the results [da], [di], [du], etc. Please note, د dāl is one of the six letters that do not connect to the left, and is used in this demonstration for clarity. Most other letters connect to Template:Unicode, Template:Unicode and Template:Unicode.

| Simple vowels | Name | Trans. | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| دَ | Template:Unicode | a | [a] |

| دِ | Template:Unicode | i | [i] |

| دُ | Template:Unicode | u | [u] |

| دَا | Template:Unicode | ā | [aː] |

| دَى | Template:Unicode | ā / aỳ | [aː] |

| دِي | Template:Unicode | ī / iy | [iː] |

| دُو | Template:Unicode | ū / uw | [uː] |

| tanwiin letters: | |

| ً, ٍ, ٌ | used to produce the grammatical endings /an/, /in/, and /un/ respectively. ً is usually used in combination with ا (اً) or taa marbuta. |

Other Symbols and Signs

Shadda

ّ šadda marks the gemination (doubling) of a consonant; kasra (when present) moves to between the shadda and the geminate (doubled) consonant.

Sukūn

An Arabic syllable can be open (ended by a vowel) or closed (ended by a consonant).

- open: CV[consonant-vowel] (long or short vowel)

- closed: CVC (short vowel only)

When the syllable is closed, we can indicate that the consonant that closes it does not carry a vowel by marking it with a sign called sukūn, which takes the form "°", to remove any ambiguity, especially when the text is not vocalised: it's necessary to remember that a standard text is only composed of series of consonants; thus, the word qalb, "heart", is written qlb. Sukūn allows us to know where not to place a vowel: qlb could, in effect, be read /qVlVbV/, but written with a sukūn over the l and the b, it can only be interpreted as the form /qVlb/ (as for knowing which vowel to use, the word has to be memorised); we write this قلْبْ.

You might think that in a vocalised text sukūn is not necessary, because the lack of vowel after a consonant might be signalled by simply not writing any mark above it, so قِلْبْ would be redundant. That is not so because such a convention ("lack of any vowel mark means lack of vowel sound") does not exist: k + u + t + b may indeed be read "kutib". Such a rule would make sense if everybody writing a vowel mark were forced to write all vowel marks in the same word, and that is not the case. In fact, you may write as many or as few of the vowel marks as you like.

In the Qurʼan, however, all vowel marks must be written: there, sukuun over a letter (other than the alif indicating long "a") indicates that it is pronounced but not followed by a short vowel, while the lack of any sign over a letter (other than alif) indicates that the consonant is not pronounced.

Outside of the Qurʼan, putting a sukuun above a yaa' which indicates long ee, or above a waaw which stands for long oo, is extremely rare, to the point that yaa with sukuun will be unambiguously read as the diphthong ai (as in English "eye") and waaw with sukuun will be read au (as in English "cow").

So, the word Template:Unicode, "husband", can be written simply Template:Unicode : زوج (which might be also read "zooj" if such a word existed); or with sukūn زوْجْ which is unambiguously "zowj"; or with sukūn and vowels: زَوْج.

The letters Template:Unicode (موسيقى with a Template:Unicode at the end of the word) will be read most naturally as the word "mooseekaa" ("music"). If you were to write sukuuns above the waaw, yaa and alif, you'd get وْسيْقىْ, which looks like "mowsaykay" (note that an Template:Unicode is an alif and never takes sukūn).

You cannot place a sukuun on the final letter ǧ of "zawǧ" even if you don't pronounce a vowel there, because fully vocalised texts are always written as if the ighraab vowels were in fact pronounced, and this word can never have a sukuun as an ighraab. Let's take the sentence "aḥmad zawǧ šarr", meaning "Ahmed is a bad husband". The theoretical pronunciation with the ighraab vowels is "aḥmadun zauǧun šarrun". Interestingly, regardless of the fact that most people say "aḥmad zauǧ šarr", you cannot write the mark for sukuun over that j; you either leave it markless, or use the mark for "un". By the same token, you can leave the final r of this sentence either completely unmarked or topped with a shadda plus "un", but a sukuun never belongs there, regardless of the fact that the only correct pronunciation of "šarrun" at the end of an utterance is "šar".

Arabic numerals

There are two kinds of numerals used in Arabic writing; standard Arabic numerals, and "East Arab" numerals, used in Iran, Pakistan and India. In Arabic, these numbers are referred to as "Indian numbers" (أرقام هندية). In most of present-day North Africa, the usual Western numerals are used; in medieval times, a slightly different set (from which, via Italy, Western "Arabic numerals" derive) was used. Unlike Arabic alphabetic characters, Arabic numerals are written from left to right.

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In addition, the Arabic alphabet can be used to represent numbers, a usage rare today. This usage is based on a different and older (abjad) order of the alphabet: أ ب ج د ه و ز ح ط ي ك ل م ن س ع ف ص ق ر ش ت ث خ ذ ض ظ غ. (In the Maghreb and West Africa, a few of these letters are transposed. See the article on abjad. ) أ ʼalif is 1, ب bāʼ is 2, ج ǧīm is 3, and so on until ي yāʼ = 10, ك kāf = 20, ل lām = 30, ... ر rāʼ = 200, ..., غ ġayn = 1000. This is sometimes used to produce chronograms.

History

The Arabic alphabet can be traced back to the Nabatean alphabet used to write the Nabataean dialect of Aramaic, itself descended from Phoenician (which, among others, gave rise to the Greek alphabet and, thence, to Etruscan and Latin letters.). The first known text in the Arabic alphabet is a late fourth-century inscription from Jabal Ramm (50 km east of Aqaba), but the first dated one is a trilingual inscription at Zebed in Syria from 512. However, the epigraphic record is extremely sparse, with only five certainly pre-Islamic Arabic inscriptions surviving, though some others may be pre-Islamic. Later, dots were added above and below the letters to differentiate them (the Aramaic model had fewer phonemes than the Arabic, and some originally distinct Aramaic letters had become indistinguishable in shape, so in the early writings 15 distinct letter-shapes had to do duty for 28 sounds!) The first surviving document that definitely uses these dots is also the first surviving Arabic papyrus (PERF 558), dated April 643, although they did not become obligatory until much later. Important texts like the Qurʼan were frequently memorized; this practice, which survives even today, probably arose partially from a desire to avoid the great ambiguity of the script.

Yet later, vowel signs and hamzas were added, beginning sometime in the last half of the sixth century, roughly contemporaneous with the first invention of Syriac and Hebrew vocalization. Initially, this was done by a system of red dots, said to have been commissioned by an Umayyad governor of Iraq, Hajjaj ibn Yusuf: a dot above = a, a dot below = i, a dot on the line = u, and doubled dots gave tanwin. However, this was cumbersome and easily confusable with the letter-distinguishing dots, so about 100 years later, the modern system was adopted. The system was finalized around 786 by al-Farahidi.

Arabic alphabets of other languages

Arabic script is not used solely for writing Arabic, but for a variety of languages. In each language, it has been modified to fit the language's sound system. There are phonemes not found in Arabic, but found in, for instance, Persian, Malay and Urdu. For example, the Arabic language lacks a "P" sounding letter, so many languages add their own "P" in the script, though the symbol used may differ between languages. These modifications tend to fall into groups; so all the Indian and Turkic languages written in Arabic tend to use the Persian modified letters, whereas West African languages tend to imitate those of Ajami, and Indonesian ones those of Jawi. The script in which the Persian modified letters are used, is called Perso-Arabic script by the scholars.

Generally, in countries where national education is effective and where the national language is written in Arabic script, Arabic script is also used to write the other languages used in that country.

The Arabic alphabet is currently used for:

- Kurdish and Turkmen in Northern Iraq. (In Turkey, the Latin alphabet is now used for Kurdish);

- Official language Persian and regional languages including Azeri, Sorani-Kurdish and Baluchi in Iran;

- Official languages Dari and Pashto and regional languages including Tajik and Uzbek in Afghanistan;

- Official language Urdu and regional languages including Punjabi (where the script is known as Shahmukhi), Sindhi, Kashmiri, and Baluchi in Pakistan;

- Urdu and Kashmiri in India (see List of national languages of India);

- Uyghur (changed to Roman script in 1969 and back to a simplified, fully voweled, Arabic script in 1983), Kazakh and Kyrgyz by a minority of Kyrgyz in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region in northwest China;

- Malay in the Arabic script known as Jawi is co-official in Brunei, and used for religious purposes in Malaysia, Indonesia, and Singapore;

- Comorian (Comorian) in the Comoros, currently side by side with the Latin alphabet (neither is official);

- Hausa for many purposes, especially religious (known as Ajami);

- Mandinka, widely but unofficially; (another alphabet used is N'Ko)

- Wolof (at zaouias), known as Wolofal.

- Tamazight and other Berber languages were traditionally written in Arabic in the Maghreb. There is now a competing 'revival' of neo-Tifinagh.

In the past, it has also been used to represent other languages. Most education was once religious instead of governmental and uniform within a state, so choice of script was determined by the user's religion and Muslims would use Arabic script to write any language they used.

- Afrikaans (as was first written among the "Cape Malays");

- Albanian;

- Azeri in Azerbaijan (now written in the Latin alphabet and Cyrillic alphabet scripts in Azerbaijan);

- Belarusian (among ethnic Tatars);

- Berber in North Africa, particularly Tachelhit in Morocco (still being considered, along with Tifinagh and Latin for Tamazight);

- Bashkir (for some years: from October Revolution (1917) until 1928);

- Bosnian;

- Chaghatai across Central Asia;

- Chechen (for some years: from October Revolution (1917) until 1928);

- Chinese and Dungan, among the Chinese Hui Muslims[1] (http://www.aa.tufs.ac.jp/~kmach/xiaoerjin/xiaoerjin-e.htm);

- Fulani, known as Ajami;

- Hebrew;

- Kazakh in Kazakhstan;

- Kyrgyz in Kyrgyzstan;

- Malay in Malaysia and Indonesia;

- Mozarabic, when the Moors ruled Spain (and later Aragonese, Portuguese, and Spanish proper; see aljamiado);

- Nubian;

- Sanskrit has also been written in Arabic script, though it is more well known as using the Devanagari script - the same script used for writing the Hindi language.

- Swahili;

- Somali (has used the Latin alphabet since 1972);

- Songhay in West Africa, particularly in Timbuktu;

- Tatar (iske imlâ) before 1928 (changed to Latin), reformed in 1880's, 1918 (deletion of some letters);

- Turkish in the Ottoman Empire was written in Arabic script until Mustafa Kemal Atatürk declared the change to Roman script in 1928. This form of Turkish is now known as Ottoman Turkish and is held by many to be a different language, due to its much higher percentage of Persian and Arabic loanwords;

- Turkmen in Turkmenistan;

- Uzbek in Uzbekistan;

- All the Muslim peoples of the USSR between 1918-1928 (many also earlier), including Bashkir, Chechen, Kazakh, Tajik etc. After 1928 their script became Latin, then later Cyrillic.

Computers and the Arabic alphabet

The Arabic alphabet can be encoded using several character sets, including ISO-8859-6 and Unicode, in the latter thanks to the "Arabic segment", entries U+0600 to U+06FF. However, neither of these sets indicate the form each character should take in context. It is left to the rendering engine to select the proper glyph to display for each character.

When one wants to encode a particular written form of a character, there are extra code points provided in Unicode which can be used to express the exact written form desired. The Arabic presentation forms A (U+FB50 to U+FDFF) and Arabic presentation forms B (U+FE70 to U+FEFF) contain most of the characters with contextual variation as well as the extended characters appropriate for other languages. These effects are better achieved in Unicode by using the zero width joiner and non-joiner, as these presentation forms are deprecated in Unicode, and should generally only be used within the internals of text-rendering software, when using Unicode as an intermediate form for conversion between character encodings, or for backwards compatibility with implementations that rely on the hard-coding of glyph forms.

Finally, the Unicode encoding of Arabic is in logical order, that is, the characters are entered, and stored in computer memory, in the order that they are written and pronounced without worrying about the direction in which they will be displayed on paper or on the screen. Again, it is left to the rendering engine to present the characters in the correct direction, using Unicode's bi-directional text features. In this regard, if the Arabic words on this page are written left to right, it is an indication that the Unicode rendering engine used to display them is out-of-date. For more information about encoding Arabic, consult the Unicode manual available at http://www.unicode.org/

- Multilingual Computing in Arabic with Windows, major word processors, web browsers, Arabic keyboards, and Arabic transliteration fonts (http://www.nclrc.org/inst-arabic3.pdf)

Arabic keyboard layout

Microsoft_Arabic_Keyboards_Madhany.png

See also

- Arabic calligraphy - considered an art form in its own right

- Arabic numerals

- ArabTeX - provides Arabic support for TeX and LaTeX

- Jawi - an adapted Arabic alphabet for the Malay language

- Unicode characters for the Arabic alphabet

External links

- Arab writing and calligraphy (http://www.al-bab.com/arab/visual/calligraphy.htm)

- Article about Arabic alphabet (http://www.omniglot.com/writing/arabic.htm)

- Arabic alphabet and calligraphy (http://www.islamicart.com/main/calligraphy/)

- aralpha (freeware) to learn the characters (http://members.aol.com/OlivThill/)

- Guide to the use of Arabic in Windows, major word processors and web browsers (http://www.uga.edu/islam/arabic_windows.html)

This article contains major sections of text from the very detailed article Arabic alphabet/from the French Wikipedia, which has been partially translated into English. Further translation of that page, and its incorporation into the text here, are welcomed.ar:عربية (كتابة) ca:Alfabet àrab cs:Arabské písmo de:Arabisches Alphabet es:Alfabeto árabe eo:Araba alfabeto fa:خط عربی fr:Alphabet arabe he:אלפבית ערבי hu:Arab ábécé nl:Arabisch alfabet ja:アラビア文字 pl:Alfabet arabski pt:Alfabeto árabe ro:Alfabetul arab sl:Arabska abeceda tt:Ğäräp älifbası zh:阿拉伯语字母表 sv:Arabiska alfabetet