Pontiac's Rebellion

|

|

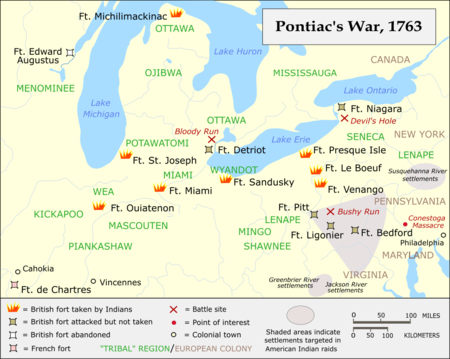

Pontiac's Rebellion was a war launched in 1763 by Native Americans ("Indians") who were dissatisfied with British rule in the Great Lakes region and the Ohio Country after the British victory in the French and Indian War. The war began in 1763 when Native Americans attacked a number of British forts and Anglo-American settlements; hostilities came to an end after British army expeditions in 1764 led to peace negotiations. The war was a failure for the Indians in that it did not drive away the British, but the widespread uprising prompted the British government to modify the policies that had provoked the conflict.

The war is named after its most famous participant, the Ottawa leader Pontiac; variations include "Pontiac's Conspiracy" and "Pontiacís Uprising." Scholars have long questioned the appropriateness of naming the war after Pontiac, since no single Native American led the conflict. Furthermore, descriptions such as "conspiracy" and "rebellion"—first used in an era when white historians wrote from an overtly racist perspective—suggest an illegitimate revolt against British authority. Alternate titles such as the "Western Indians' Defensive War of 1763" have not caught on; the predominant usage among historians today is "Pontiac's War."

Today, perhaps the best-known incident from the war is when British officers at Fort Pitt attempted to infect the attacking Indians with blankets that had been exposed to smallpox. (See "Siege of Fort Pitt" below.)

| Contents |

Origins of the war

| Origins of Pontiac's War |

|---|

| *Military occupation |

| *Perceived insults |

| *Gift giving |

| *Trade restrictions |

| *Religious revival |

| *Colonial expansion |

- You think yourselves Masters of this Country, because you have taken it from the French, who, you know, had no Right to it, as it is the Property of us Indians. --Nimwha, Shawnee diplomat, to George Croghan, 1768

Although the French and Indian War did not officially end until 1763, the fighting in North America came to an end after British General Jeffrey Amherst captured French Montrťal in 1760. British troops proceeded to occupy the various forts in the Ohio Country and Great Lakes region previously garrisoned by the French. Before long, Native Americans who had been allies of the defeated French found themselves increasingly dissatisfied with the British occupation and the new policies imposed by the victors. In essence, while the French had long cultivated alliances among the Indians, the British post-war approach was to treat the Indians as a conquered people.

General Amherst was in overall charge of administering Indian policy. The British Crown was looking to reduce expenses after a costly war, and so in 1761 Amherst began to cut back on the gifts and provisions customarily distributed to the Indians. Amherst, who made little effort to conceal his contempt for Native Americans, considered diplomatic gift giving to be unnecessary now that the British did not have to compete with the French for the allegiance of the Indian tribes. However, Native Americans of the region considered this gift giving to be an essential part of a reciprocal relationship. In refusing to share some of their bounty with the Indians as the French had done, the British were not fulfilling their obligations as leaders, and the Indians felt insulted. Sir William Johnson, the Superintendent of the Indian Department, tried to warn Amherst of the dangers of this frugal policy, to no avail.1

Amherst also outlawed the sale of alcohol to Indians, which created much resentment among some tribesmen. Additionally, the Indians needed gunpowder and ammunition for hunting in order to provide food for their families and to procure skins for trading. While the French had always made gunpowder and ammunition available, Amherst did not trust his former Indian adversaries and so restricted the distribution of these supplies.

Furthermore, in the early 1760s a religious awakening was sweeping through Indian settlements in the region, which was fed by discontent with the British as well as food shortages and epidemic disease. The most influential individual in this phenomenon was Neolin, known as the "Delaware Prophet," who called upon Indians to shun the trade goods, alcohol, and weapons of the whites. Merging elements from Christianity into traditional religious beliefs, Neolin told listeners that the Master of Life was displeased with the Indians for taking up the bad habits of the white men, and that the British posed a threat to their very existence. "If you suffer the English among you," said Neolin, "you are dead men. Sickness, smallpox, and their poison [alcohol] will destroy you entirely." It was a powerful message for a people whose world was changing by forces that seemed to be beyond their control.2

Another cause of the war was the issue of land. While the French colonists had always been relatively few in number, there seemed to be no end of settlers in the British colonies, which inevitably compelled native villages in the east to relocate further west. Delaware and Shawnees in the Ohio Country had been displaced by expanding white settlement, and this motivated their involvement in the war. However, as historian Gregory Dowd emphasizes, Pontiac and his allies around Detroit had not been much affected by white settlement, and even the Delawares and Shawnees "were under no immediate threat of dispossession." The presence of British troops, not British settlers, was the pressing problem. The expansion of white settlement was a contributing factor—but not a primary cause—of Pontiac's War.3

Attacks on the British forts, 1763

All of the above factors contributed to the outbreak of the war in 1763, which began at Fort Detroit under the local leadership of Pontiac, and quickly spread to other British forts in the region. Eight forts fell to Indian attackers; others, including Fort Detroit and Fort Pitt, were unsuccessfully besieged. In his 1851 book The History of the Conspiracy of Pontiac, historian Francis Parkman portrayed these attacks as a carefully coordinated operation planned by Pontiac. Parkman's interpretation remains well known, but some historians have long pointed out that there is no reliable evidence that Pontiac—or anyone else—planned these attacks in advance. Rather than the product of a master plan, it is possible that the war evolved spontaneously, as Pontiac's actions at Detroit inspired other already discontented Indians to similarly take up arms against the British. Likewise, although it was widely assumed at the time that Frenchmen were secretly instigating the war, the evidence for this is also slight. Although Pontiac frequently spoke of reviving the Franco-Indian alliance, his rhetoric was probably intended to inspire the French to support him, rather than an indication that he had French backing.4

Siege of Fort Detroit

On April 27, 1763, Pontiac spoke at a council about 10 miles below Detroit. Using the teachings of Neolin to inspire his listeners, Pontiac convinced a number of Ottawas, Ojibwas, Potawatomis, and Hurons to join him in an attempt to seize Fort Detroit and drive out the British. According to a French chronicler, Pontiac proclaimed:

- "It is important for us, my brothers, that we exterminate from our lands this nation which seeks only to destroy us. You see as well as I that we can no longer supply our needs, as we have done from our brothers, the French. [...] From all this you can see well that they are seeking our ruin. Therefore, my brothers, we must all swear their destruction and wait no longer. Nothing prevents us; they are few in numbers, and we can accomplish it."5

On May 7, Pontiac entered the fort with about 300 men, armed with sawed-off muskets and other weapons hidden under blankets, determined to take the fort by surprise. However, the British commander had apparently been informed of Pontiacís plan, and the garrison of about 120 men was armed and ready. Pontiac withdrew and, two days later, laid siege to the fort. A number of British soldiers and settlers in the area outside the fort were captured or killed. Eventually more than 900 Indian warriors from a half-dozen tribes joined the siege.

Late in July, British reinforcements arrived at Fort Detroit and, on July 31, 1763, about 250 men attempted to make a surprise attack on Pontiacís encampment. Pontiac was ready and waiting, and defeated the British at the Battle of Bloody Run. However, the situation at the fort remained a stalemate, and Pontiacís influence among his followers began to wane. Groups of Indians began to abandon the siege, some of them making peace with the British before departing. On October 31, 1763, finally convinced that the French in Illinois would not come to his aid, Pontiac lifted the siege and removed to the Maumee River, where he continued his efforts to rally resistance against the British.

Small forts taken

- Fort Sandusky (on the site of Sandusky, Ohio) was taken on May 16, 1763 by Wyandot Indians, using the same stratagem that had failed in Detroit. The Indians had gained entry to the fort under the pretense of holding a council, and then seized the commander and killed the fifteen-man garrison. A great number of British traders were put to death as well, and the fort was burned.

- Fort St. Joseph (on the site of the present Niles, Michigan) was captured on May 25, 1763 by the same method as at Sandusky. The commander was seized by Potawatomis, and most of the fifteen-man garrison was killed outright.

- Fort Miami (on the site of present Fort Wayne, Indiana) was the third fort to fall. On May 27, 1763, the commander was lured out of the fort by his Indian mistress and shot dead by Miami Indians. The nine-man garrison surrendered after the fort was surrounded.

- Fort Ouiatenon (about 5 miles southwest of present Lafayette, Indiana) was taken by Indians on June 1, 1763. Soldiers were lured outside for a council, and the entire twenty-man garrison was taken captive without bloodshed.

- Fort Michilimackinac (Mackinac), Michigan, was the largest fort taken by surprise. On June 4, 1763, local Ojibwas had staged a kind of lacrosse game with visiting Sauks. The soldiers watched the game, as they had done on previous occasions. The ball was hit through the open gate of the fort; the teams rushed in and were then handed weapons previously smuggled into the fort by Indian women. About fifteen men of the 35 man garrison were killed in the struggle; five more were later executed.

- Fort Venango (near the site of the present Venango, Pennsylvania) was taken around June 16, 1763 by Senecas. The entire twelve-man garrison was killed.

- Fort Le Boeuf (on the site of Waterford, Pennsylvania) was attacked on June 18, possibly by the same Senecas who had destroyed Fort Venango. Most of the twelve-man garrison escaped to Fort Pitt.

- Fort Presque Isle (on the site of Erie, Pennsylvania) was surrounded by about 250 Ottawas, Ojibwas, Wyandots, and Senecas on June 19, 1763. After holding out for two days, the garrison of approximately sixty men surrendered on the condition that they could return to Fort Pitt. Most were instead murdered after emerging from the fort.

Siege of Fort Pitt

Fort Pitt, with a garrison of 330 men (and over 200 women and children inside), was attacked on June 22, 1763, primarily by Delaware (Lenape) Indians. Too strong to be taken by force, the fort was kept under siege throughout July. Meanwhile, Delaware and Shawnee war parties raided deep into the Pennsylvania settlements, taking captives and killing unknown numbers of men, women, and children who were living on what was Indian land a generation earlier. Panicked settlers fled eastwards.

For General Amherst, who before the war had dismissed the possibility that the Indians would offer any effective resistance to British rule, the military situation over the summer became increasingly grim. He wrote his subordinates and instructed them not to take any Indian prisoners. To Colonel Henry Bouquet at Lancaster, Pennsylvania, who was preparing to lead an expedition to relieve Fort Pitt, Amherst made the following proposal on about 29 June 1763: "Could it not be contrived to send the small pox among the disaffected tribes of Indians? We must on this occasion use every stratagem in our power to reduce them."6

Bouquet agreed, writing to Amherst on 13 July 1763: "I will try to inoculate the bastards with some blankets that may fall into their hands, and take care not to get the disease myself." Amherst responded favorably on 16 July 1763: "You will do well to inoculate the Indians by means of blankets, as well as every other method that can serve to extirpate this execrable race."7

As it turned out, however, officers at the besieged Fort Pitt had already attempted to do what Amherst and Bouquet were still discussing. During a parley at Fort Pitt on 24 June 1763, Captain Simeon Ecuyer (the commander at Fort Pitt) gave representatives of the besieging Delawares two blankets and a handkerchief that had been exposed to smallpox, in hopes of spreading the disease to the Indians in order to end the siege. Indians in the area did indeed contract smallpox. However, some historians have noted that it is impossible to verify how many people (if any) contracted the disease as a result of the Fort Pitt incident; the disease was already in the area and may have reached the Indians through other vectors. Indeed, even before the blankets had been handed over, the disease may have been spread to the Indians by native warriors returning from attacks on infected white settlements. So while it is certain that these British soldiers attempted to intentionally infect Indians with smallpox, it is uncertain is whether or not their attempt was successful.8

On August 1, 1763, most of the Indians broke off the siege at Fort Pitt in order to intercept a body of 500 British troops marching to the fort under Colonel Bouquet. On August 5, these two forces met at the Battle of Bushy Run. Bouquet fought off the attack and relieved Fort Pitt on August 20.

End of the 1763 campaign

Fort Niagara, one of the most critical western forts, was not assaulted, but on September 14, 1763 at least 300 Senecas, Ottawas, and Ojibwas attacked a supply train along the Niagara Falls portage. Two companies sent from Fort Niagara to rescue the supply train were also defeated. Seventy-two soldiers and wagoners were killed in these actions, which Anglo-Americans called the "Devil's Hole Massacre."

At this point, major combat in Pontiac's War was effectively over. Although the Indians had won many small victories in 1763, they were short of ammunition by the end of the year, and the large forts remained in British hands. About 450 British soldiers had been killed in the fighting; total Indian losses are unknown. Approximately 4,000 white settlers from Pennsylvania and Virginia had been compelled to flee their homes. The number of white settlers killed has often been given as 2,000, although Gregory Dowd writes that this figure "cannot be taken seriously" because the estimate was a "wild guess" made by George Croghan while in faraway London. Historian Daniel Richter characterizes the Indian offensive of 1763 as a campaign of ethnic cleansing. Before the British military could effectively seize the initiative in the war, an angry group of Pennsylvanians responded to the violence with an ethnic cleansing campaign of their own.9

British response

The Paxton Boys' Uprising

The violence and terror of Pontiac's War convinced many white Pennsylvania frontiersmen that their government was not doing enough to protect them. This discontent was manifest most seriously in an uprising led by a vigilante group that came to be known as the Paxton Boys, so-called because they were primarily from the area around the Pennsylvania village of Paxtang (Paxton).

The Paxtonians turned their anger towards Native Americans—many of them Christians—who lived peacefully in small enclaves in the midst of white Pennsylvania settlements. On December 14, 1763 a group of more than fifty Paxton Boys marched on an Indian village and murdered the six Conestoga (or Susquehannock) Indians they found there. The remaining fourteen Susquehannocks were placed in protective custody in Lancaster in order to protect them from the Paxton mob. This failed: on December 27, Paxton Boys broke into the workhouse at Lancaster and brutally slaughtered all fourteen Indians. These two actions, which resulted in the deaths of all but two of the last of the Susquehannocks, are sometimes known as the Conestoga Massacre. Governor John Penn issued bounties for the arrest of the murderers, but no one came forward to identify them.

The Paxton Boys then set their sights on other Indians living within eastern Pennsylvania, many of whom fled to Philadelphia for protection. Several hundred Paxtonians then marched on Philadelphia in January of 1764, where the presence of British troops and Philadelphia militia prevented them from doing more violence. Benjamin Franklin, who had raised the local militia, negotiated with the Paxton leaders and brought an end to the immediate crisis.

Expeditions and negotiations

Bouquettreaty.jpg

General Amherst, held responsible for the Indian uprising by the Board of Trade, was recalled to London in August of 1763. He was replaced by Major General Thomas Gage, who paid more attention to William Johnson's advice regarding Indian policy. There was a shift in overall approach, as Gage and Johnson worked to bring an end to the conflict through diplomatic as well as military means.

On July 11 1764, Johnson opened a treaty conference at Fort Niagara with about 2,000 Indians, primarily members of the Iroquois League. Because of the diplomatic ties between the Iroquois and the British colonies (the Covenant Chain relationship), most Iroquois had not taken part in the war. Nevertheless, the westernmost Iroquois peoples—Senecas from Genesee River valley—had taken up arms against the British, and Johnson worked to bring them back into the fold. As restitution for the Devil's Hole ambush, the Senecas were compelled to cede the strategically important Niagara portage to the British. Johnson also worked to diplomatically isolate the Delawares and Shawnees from the Six Nations, convincing some Oneidas and Tuscarawas to send out a war party against the Ohio Indians.

With the area around Fort Niagara more secure, the first of two military expeditions began. On August 6, 1764, Colonel John Bradstreet set out from Fort Niagara with about 1,200 British soldiers and a large contingent of Native Americans. Bradstreet's ultimate goal was to reach Detroit and bring Pontiac to terms. Moving along Lake Erie, the expedition stopped at Presque Isle on August 12, where Bradstreet negotiated a treaty with a number of Ohio Indians including the Seneca-Mingo leader Guyasuta. However, Bradstreet exceeded his authority in making this agreement, since the terms called for the halt of the expedition led by Colonel Henry Bouquet (see below). Bradstreet's superiors believed that the Ohio Indians only made peace with Bradstreet in order to stop Bouquet, and so General Gage rejected Bradstreet's treaty. Bradstreet continued on to Detroit and conducted more negotiations, but Pontiac, still hopeful of reviving French support, refused to meet with him.

On October 3, 1764, Colonel Bouquet set out from Fort Pitt with 1,150 men, marching to the Muskingum River in the Ohio Country, within striking distance of a number of native villages. Bouquet negotiated with Delawares, Shawnees, and Mingos, demanding that they return all captives, including those not yet returned from the French and Indian War. The Indians were compliant, since they were low on ammunition and isolated now that treaties had been negotiated at Fort Niagara and Fort Detroit. With reluctance, the Indians turned over more than 200 captives to Bouquet, most of who had been adopted into Indian families. A number of these people—primarily those who had lived with the Indians since childhood—were reluctant to leave, and Bouquet had to use guards to prevent them from returning to the Indians. Not all of the captives were present, and the Indians were compelled to surrender some hostages as a guarantee that the other captives would be returned to the British colonies.

Bouquet returned to Fort Pitt in November without having fired a shot. His expedition is usually portrayed as a decisive, victorious end to Pontiac's War, demonstrating the weakness of the Indians and the power of the British military. Some historians question that interpretation, noting that Bouquet was compelled to stop short of his goal of punishing the leaders of the war, since his position in the Ohio Country as winter approached was quite vulnerable.

Indeed, in 1765 the British decided that the occupation of the former French forts further west in the Illinois Country could only be accomplished by diplomatic—not military—means. Johnson's deputy George Croghan travelled to the Illinois Country that summer, and although he was injured along the way in an attack by Kickapoo and Mascouten warriors, he managed to meet and negotiate with Pontiac. British officials were under the mistaken notion that Pontiac had more power than he actually possessed; paradoxically, by making Pontiac the focus of their diplomatic efforts, they greatly increased his stature. Pontiac, now certain that the French would not come to his aid, agreed to travel to New York, where he made a more formal treaty with William Johnson on 25 July 1766 at Fort Ontario. It was hardly a surrender: no lands were ceded, no prisoners returned, and no hostages were taken.

Aftermath

This war worsened Britain's financial health and resulted in the Proclamation of 1763, preventing the colonists from moving westward.

Notes

- Note 1: White, p. 180, 286; Dowd, War Under Heaven, pp. 70-75; Anderson, pp. 469-71; McConnell p. 164.

- Note 2: Neolin quoted in Dowd, A Spirited Resistance, p. 34.

- Note 3: Dowd, War Under Heaven, pp. 82-3.

- Note 4: Peckham (p. 108n) found no evidence of Pontiac's leadership beyond Detroit, but found circumstantial evidence of French involvement; Dowd (War Under Heaven, pp. 105-13) doubts French involvement.

- Note 5: Quoted in Peckham, pp. 119-20.

- Note 6: Peckham, p. 226; Anderson, p. 542; 809n.

- Note 7: Anderson, p. 809n; Grenier, p. 144.

- Note 8: Anderson, pp. 541-2; McConnell, p. 195; Dowd, War Under Heaven, p. 190.

- Note 9: British soldiers killed, Peckham p. 239; 4,000 white refugees, War Under Heaven p. 275; "not taken seriously", War Under Heaven p. 142; ethnic cleansing, Richter p. 190.

References

- Anderson, Fred. Crucible of War: The Seven Yearsí War and the Fate of Empire in British North America, 1754-1766. New York: Knopf, 2000. ISBN 0375406425. (discussion (http://www.common-place.org/vol-01/no-01/crucible/crucible-delay.shtml))

- Dowd, Gregory Evans. A Spirited Resistance: The North American Indian Struggle for Unity, 1745-1815. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1992.

- ———. War Under Heaven: Pontiac, the Indian Nations, & the British Empire. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2002. (review (http://www.common-place.org/vol-03/no-03/reviews/shannon.shtml))

- Grenier, John. The First Way of War: American War Making on the Frontier, 1607-1814. Cambridge University Press, 2005.

- McConnell, Michael N. A Country Between: The Upper Ohio Valley and Its Peoples, 1724-1774. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 1992. (review (http://publications.ohiohistory.org/ohstemplate.cfm?action=detail&Page=0103115.html&StartPage=75&EndPage=117&volume=103&newtitle=Volume%20103%20Page%2075))

- ———. "Introduction to the Bison Book Edition" of The Conspiracy of Pontiac by Francis Parkman. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 1994. ISBN 080328733.

- Parkman, Francis. The Conspiracy of Pontiac and the Indian War after the Conquest of Canada. 2 volumes. Originally published Boston, 1851. Parkman's landmark work has long been considered unreliable by academic historians, but Parkman's prose is still much admired.

- Peckham, Howard H. Pontiac and the Indian Uprising. University of Chicago Press, 1947.

- Richter, Daniel K. Facing East from Indian Country: A Native History of Early America. Cambridge, Massachusettes: Harvard University Press, 2001. (review (http://www.common-place.org/vol-03/no-03/reviews/oberg.shtml))

- White, Richard. The Middle Ground: Indians, Empires, and Republics in the Great Lakes Region, 1650-1815. Cambridge Universtiy Press, 1991. (info (http://www.washington.edu/research/showcase/1990a.html))

External links

- Ohio History Central: Pontiac's War (http://www.ohiohistorycentral.org/ohc/history/h_indian/events/pontwar.shtml)

- U-S-History.com: Early Pennsylvania History - Pontiac's Rebellion (http://www.u-s-history.com/pages/h598.html)

- "Colonial Germ Warfare" (http://www.history.org/Foundation/journal/Spring04/warfare.cfm) - (article from Colonial Williamsburg Journal)

- "Chief Pontiac's siege of Detroit" - article from The Detroit News (http://info.detnews.com/history/story/index.cfm?id=180&category=events)

- "Broken Promises, Broken Dreams: North America's Forgotten Conflict at Bushy Run Battlefield" (http://www.phmc.state.pa.us/ppet/bushyrun/page1.asp?secid=31) (article originally from Pennsylvania Heritage Magazine)

- "Battle of Bushy Run" from mohicanpress.com (http://www.mohicanpress.com/bushy_run.html)

- The War Chief of the Ottawas by Thomas Guthrie Marquis, 1915 (online book) (http://www.gutenberg.org/dirs/1/5/5/2/15522/15522.txt)de:Pontiac-Aufstand