History of Pakistan

|

|

Pakistan, along with India, was one of two states created out of the territory of British colonial India in 1947. In 1971, East Pakistan became independent as Bangladesh.

Prehistory and early civilization

Earliest settlements

The Bolan river runs through the Bolan Pass in Baluchistan, Pakistan, a natural passageway connecting the Indus plain to the Iranian plateau. The Bolan region is home to Mehrgarh, the earliest known agricultural settlement in Pakistan, dating from about 7000 BCE.

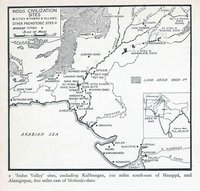

Indus Valley Civilization

The Indus Valley Civilization, 2800 BCE-1800 BCE, was one of the most ancient civilizations, thriving along the Indus River and other rivers of the Indus basin in what is now Pakistan. The Indus Valley Civilization is also sometimes referred to as the Harappa or Harappan Civilization of the Indus Valley, in reference to the city of Harappa, located in Punjab, Pakistan. Another large city, Mohenjo-daro, is located in Sind.

Indusvalleyexcavation.jpg

Other nearby sites include those found in modern northwest India as well as sites in Baluchistan, notably Kej, and even as far northwest as the North-West Frontier Province where the remains of a city-state called Judeiro-Daro can be found. The people of the Indus civilization may have been an Elamo-Dravidian people, possibly related to the Elamite people of southern Iran and to the Dravidians of India, but this remains a speculative theory at present. The Indus civilization appears to have maintained commercial and diplomatic ties with the nearby Sumerian/Babylonian civilization of Iraq as well as Central Asia and possibly Egypt. Colonies from the Indus civilization spanned a vast area from northwest India to Afghanistan. This civilization declined around 1500-1900 BCE One major theory is that the Indus Valley civilization was crushed by successive invasions (circa 2000 BCE and 1400 BCE) of Aryans, Indo-European warrior tribes who came from somewhere around the Black Sea (see Aryan invasion). Other theories seem to point towards an internal decay, even an internecine conflict (ancient mercenaries may be implicated), within the Indus Valley civilization prior to the alleged Aryan invasions.

To date, over 1,052 cities and settlements have been found, mainly in the general region of the Indus River in Pakistan.

Ancient Pakistan

Achaemenid rule

Map_of_Iran_Achaemenid_Dynasty.gif

Ancient Pakistan was ruled by the Persian Achaemenid empire from c.520 BCE in the reign of Darius the Great to its conquest by Alexander the Great. It became part of the empire as a satrapy that included the lands of present-day Pakistani Punjab, the Indus river from the borders of Gandhara down to the Arabian Sea, together with other parts of the Indus plain, According to Herodotus of Halicarnassus, it was the most populous and richest satrapy of the twenty satrapies of the empire. Troops levied from Pakistan are quoted by Herodotus as being part of the army of the Achaemenid Persian emperor Xerxes who led them in an expedition to invade Ancient Greece. Achaemenid rule lasted about 186 years. The Achaemenids used Aramaic script for the Persian language. After the end of Achaemenid rule, the use of Aramaic script in the Indus plain was diminished, although we know from Asokan inscriptions that it was still in use two centuries later. Other scripts, such as Kharosthi (a script derived from Aramaic) and Greek became more common after the arrival of the Macedonians and Greeks.

Greco-Buddhist period

Overview

Greco-Buddhism, sometimes spelled Gręco-Buddhism, is the cultural syncretism between the culture of Classical Greece and Buddhism, which developed over a period of close to 800 years in the area corresponding to modern-day Afghanistan and Pakistan, between the 4th century BCE and the 5th century CE. Greco-Buddhism influenced the artistic (and, possibly, conceptual) development of Buddhism, and in particular Mahayana Buddhism, before it was adopted by Central and Northeastern Asia from the 1st century CE, ultimately spreading to China, Korea and Japan.

Alexander' conquest of ancient Pakistan, was followed by over a century of Mauryan rule based in what is today India, in the 4th century BCE. Ancient Pakistan came to be dominated by the Bactrian Greeks and later the Indo-Greeks. King Demetrius led a Bactrian Greek army that conquered the region by 200 BCE and subsequently rulers such as the Indo-Greek Menander showed an unusual syncretic fusion of cultures as the Indo-Greeks appear to have embraced Buddhism during this period. The Indo-Greek descendants of Alexander's armies and later colonists of Bactrian Greek extraction saw the most creative period of the Gandhara (Buddhist) culture. In the Punjab and the east the Greeks were often referred to as "Yavana" in Pali, or "Yonani" in Persian, derived from "Ionian", as many of the Greek colonists were from the Ionian coast. The remnants of the Indo-Greeks were subdued and assimilated by Central Asian conquerers including the Scythians (Sakas) and Parthians who ruled the region from the first century BCE to the middle of the first century of the common era. Another Central Asian group, the Tocharian Kushans arrived and would rule Pakistan for three centuries.

Alexander the great

The interaction between Hellenistic Greece and Buddhism started when Alexander the Great conquered Asia Minor, the Achaemenid Empire and ancient Pakistan in 334 BCE, defeating Porus at the Battle of the Hydaspes (near modern-day Jhelum, Pakistan) and conquering much of the Punjab. Alexander's troops refused to go beyond the Beas river — which today runs along part of the Indo-Pakistan border — and he took most of his army southwest, adding nearly all of ancient Pakistan to his empire.

Alexander created garrisons for his troops in his new territories, and founded several cities in the areas of the Oxus, Arachosia, and Bactria, and Macedonian/Greek settlements in Gandhara (see Taxila) and the Punjab. The regions included the Khyber Pass — a geographical passageway south of the Himalayas and the Hindu Kush mountains — and the Bolan Pass, on a trade route connecting Drangiana, Arachosia and other Persian and Central Asia areas to the lower Indus plain. It is through these regions that most of the interaction between India and Central Asia took place, generating intense cultural exchange and trade. The Hellenic-influenced Gandhara culture would flourish for several centuries after Alexander.

Mauryan period

The Mauryan dynasty lasted about 180 years, nearly as long as Achaemenid rule, and began with Chandragupta Maurya. Chandragupta Maurya lived in Taxila and met Alexander, and had many opportunities to observe the Macedonian army there. According to Plutarch, Alexander encouraged him to invade the Gangetic kingdom (of Magadha) by capitalizing on the extreme unpopularity of the reigning monarch. Chandragupta recruited warriors from among the northwestern hill tribes and trained them in Macedonian fighting techniques, With this army, and with Macedonian mercenaries, Chandragupta went east to the Gangetic plain to overthrow the Nanda dynasty in Magadha, thereby founding the Maurya dynasty.

Following Alexander's death on June 10, 323 BCE, his Diadochi (generals) founded their own kingdoms in Asia Minor and Central Asia. General Seleucus set up the Seleucid Kingdom, which included ancient Pakistan. Chandragupta Maurya, taking advantage of the fragmentation of power that followed Alexander's death, invaded and captured the Punjab and Gandhara. Later, the Eastern part of the Seleucid Kingdom broke away to form the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom (3rd–2nd century BCE).

Ashoka the Great

Ashokan_empire.gif

Ashoka the Great was the ruler of the Mauryan empire from 273 BC to 232 BC. A convert to Buddhism, Ashoka reigned over most of the Indian subcontinent, from present day Afghanistan to Bengal and as far south as Mysore. According to secular historians, Asoka was the first Indian emperor to rule such a large area, being comparable in size to present-day India.

He converted to the Buddhist faith following remorse for his bloody conquest of the kingdom of Kalinga in Orissa. He became a great proselytiser of Buddhism, and sent Buddhist emissaries to many lands. He set in stone the Edicts of Asoka. In ancient Pakistan, nearly all of the Asokan edicts are written either in the Aramaic script (Aramiac had been the lingua franca of the Achaemenid empire) or in Kharosthi, a script derived from Aramaic.

Brhadrata, the last ruler of the Mauryan dynasty, ruled territories that had shrunk considerably from the time of emperor Ashoka, but he was still upholding the Buddhist faith. He was assassinated in 185 BCE by his general Pusyamitra Sunga, who made himself the ruler and established the Sunga dynasty. The assassination of Brhadrata and the rise of the Sunga empire led to a wave of persecution for Buddhists, and a resurgence of Hinduism.

Indo-Greeks

The Sunga persecution also triggered the 180 BCE invasion of northern India by the king Demetrius (the son of the Greco-Bactrian king Euthydemus) going as far as Pataliputra and established an Indo-Greek kingdom that lasted nearly two centuries, until around 10 BCE.Demetrius_I_of_Bactria.jpg

The invasion was completed by 175 BCE, and the Sungas were confined to the east, although the Indo-Greeks lost some territory in the Gangetic plain. Meanwhile in Bactria, the usurper Eucratides overcame the Euthydemid dynasty, killing Demetrius in battle.

Menander

Menander_(Alexandria-Kapisa).jpg

Obv: King Menander throwing a spear.

Rev: Athena with thunderbolt. Greek legend: BASILEOS SOTIROS MENANDROY "King Menander, the Saviour".

Menander I was one of the Greek kings of the Indo-Greek Kingdom in ancient Pakistan from 155 to 130 BC. He had been a general under king Demetrius, who was killed in battle. As a general, Menader drove the Greco-Bactrians out of Gandhara and beyond the Hindu Kush, becoming king shortly after his victory.

Menander's territories covered the eastern dominions of the divided Greek empire of Bactria (from the areas of the Panjshir and Kapisa) and extended to the modern Pakistani province of Punjab with diffuse tributaries to the south and east, possibly even as far as Mathura.

Menander is one of the few Bactrian kings mentioned by Greek authors, among them Apollodotus of Artemita, who claim that he was an even greater conqueror than Alexander the Great. Strabo (XI.II.I) says Menander was one of the two Bactrian kings who extended their power farthest into India.

Sagala (modern Sialkot) became his capital and propered greatly under Menander's rule. His reign (c.155 BC - c.80 BC) was long and successful. Generous findings of coins testify to the prosperity and extension of his empire.

The Milinda Pańha, a classical Buddhist text praises Menander, saying that "as in wisdom so in strength of body, swiftness, and valour there was found none equal to Milinda in all India " (Translation by T. W. Rhys Davids, 1890)

Fragmented Indo-Greek kingdoms

Menander's empire survived him in a fragmented manner until the last independent Greek king, Hermaeus, disappeared around 10 AD.

The Indo-Greeks suffered a new attack from the descendants of Eucratides around 125 BCE, as the Greco-Bactrian king Heliocles, son of Eucratides, was fleeing from the invasion of the Yuezhi in Bactria and trying to relocate in Gandhara. The Indo-Greeks retreated to their territories east of the Jhelum River as far as Mathura, and the two houses coexisted in the northern Indian subcontinent.

Various kings ruled into the beginning of the 1st century CE, as petty rulers (such as Theodamas) and as administrators, after the conquests of the Indo-Scythians, Indo-Parthians and Yuezhi.

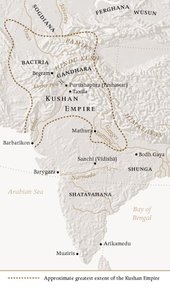

Kushan Empire

Indo-Greek rule was followed by the Kushan Empire (1st–3rd century CE).

Kanishka is renowned in Buddhist tradition for having convened a great Buddhist council in Kashmir. This council is attributed with having marked the official beginning of the pantheistic Mahayana Buddhism and its scission with Nikaya Buddhism. Kanishka also had the original Gandhari vernacular, or Prakrit, Mahayana Buddhist texts translated into the high literary language of Sanskrit. Along with the Indian king Ashoka, the Indo-Greek king Menander I (Milinda), and Harsha Vardhana, Kanishka is considered by Buddhism as one of its greatest benefactors.

The art and culture of Gandhara, at the crossroads of the Kushan hegemony, are the best known expressions of Kushan influences to Westerners.

The interaction of Greek and Buddhist cultures continued over several centuries. The Kushan empire collapsed with the invasion of the Sassanian Persians in the middle of the 3rd century CE). From this period onwards Pakistan remained under the rule of the remnants of various Kushan-Parthian powers, while the Persian Sassanians held the western and southern regions stretching from Baluchistan to Sind. The invading White Huns in the fifth century CE replaced both the Sassanians and Kushans in Pakistan.

It is also surmised that sometime during the first millennium CE, Pashtun tribes began their expansion into western Pakistan and would begin to supplant earlier Indo-Iranian tribes. Iranian-Kurdish Baluchi tribes appear to have not arrived in Pakistan until the early second millennium CE.

Buddhism however, appears to have taken root and remained the dominant faith, while Hinduism and Zoroastrianism as well as pagan religions made up sizeable and influential minorities. See also: History of Buddhism, Indo-Greek, Menander, and Ashoka

Pakistan in the Middle Ages

Pakistan's Islamic history began with the arrival of Muslim invaders in the 8th century CE. Led by a young Syrian Arab chieftain named Mohammed bin Qasim, 6,000 Muslim Syrian Arabs conquered what is today Sind and advanced as far north as Panjab past Multan in 712 CE. Expeditions were sent as far afield as Kashmir. From this period onwards, conversion to Islam led to the rapid decline of Buddhism in the region. For nearly three centuries much of what is today Pakistan existed as part of the vast Muslim Arab empire which stretched from Spain to Sind.

Following the decline of Muslim Arab rule, Central Asian Turks began to arrive in the 11th century. The Turkic rule of Mahmud of Ghazni (hailing from a region in modern Afghanistan) and subsequent Turkic rulers lasted until the 12th century. Turkic-Afghan invaders starting with Mohammed Ghori forged a vast empire that would also be replaced by another wave of Turkic invaders who formed what came to be known as the Turkic slave dynasties of Khilji dynasty, Tughlaq dynasty, and Syed who formed a vast Islamic empire that spanned much of South Asia and was known as the Delhi Sultanate and lasted until the 16th century. Pakistan west of the Indus came under the brief control of Mongol invaders in the 13th century and would shift between Islamic powers based in northern India and Iran.

During the 16th and 17th centuries, the Mughul Empire dominated most of South Asia, including much of present-day Pakistan. Founded by the Uzbek-born Babur (and briefly interrupted by the rule of the Pashtun/Afghan ruler Sher Shah Suri) whose capital at Kabul was later moved to Dehli by subsequent members of his dynasty, the Mughal Empire was one of the three major modern Islamic empires (the others being the Safavids of Persia and the Ottoman Empire of Turkey). Mughal emperors built various monuments such as the Taj Mahal (built by order of Shah Jehan) and the Shalimar Gardens of Lahore as well as the Badshahi Mosque (built during the reign of Aurangzeb) and the emperor Akbar was known for espousing an early form of multicultural tolerance. The Mughal dynasty is part of modern Pakistan's revered past, especially in the eastern provinces of Panjab and Sind. This empire's rule in Pakistan lasted for another two centuries until the invasions of the Turko-Iranian ruler Nadir Shah and the Pashtun Abdali chieftain Ahmad Shah Durrani which led to the annexation of Pashtun/Afghan territories in western Pakistan as well as the Panjab, Sind, and Kashmir to the Afghan empire from 1747 to 1800 (the Durrani period is conversely part of a revered past in western Pakistan). This short-live empire disintegrated in 1800 and Pakistan devolved into regional states following the Afghan-Sikh wars (see also Ranjit Singh) in the early 19th century. A Baluchi dynasty held sway in the south, while Sikhs and Pashtuns controlled and contested the north until the coming of the British.

British traders arrived in Bengal to the distant east in 1601 and the British Empire did not reach the region that would form modern Pakistan until the latter half of the 18th century. After 1850, the British or those influenced by them governed virtually the entire subcontinent (see British raj) and beyond. Pakistan's eastern provinces came under direct British rule, while the western regions were wrested in the latter half of the 19th century following the second of the first two Anglo-Afghan wars. The Durand Line divided the traditionally Pashtun territories of the Northwest Frontier and adjacent regions in Baluchistan and the Northern Areas from Afghanistan. The British held a tenuous peace in the area and granted additional autonomy to the fiercely independent Pashtun tribes who did not recognize the borders and would often cross back and forth with little regard to the arbitrary border. The region that would become Pakistan was pivotal in the Great Game, a strategic early cold war between the British and the Russian empire that had advanced into Central Asia.

Background to creation of Pakistan

In the early 20th century, South Asian leaders began to agitate for a greater degree of autonomy. Growing concern about Hindu domination of the Indian National Congress Party, the movement's foremost organization, led Muslim leaders to form the all-India Muslim League in 1906. In 1913, the League formally adopted the same objective as the Congress -- self-government for India within the British Empire -- but Congress and the League were unable to agree on a formula that would ensure the protection of Muslim religious, economic, and political rights.

The concept of Pakistan was first created by Syed Ahmed Khan, an Indian Muslim, who proposed that Muslims within India comprised a separate country next to the Hindu country. As the possibility of independence from British colonialism grew close, this idea gained in popularity among Indian Muslims, who were not keen to become a minority and possibly be subjugated to Hindu rule. The concept was given the name Pakistan by a student, Choudhary Rahmat Ali. Pakistan means "land of the pure", and also stands for the provinces it would include: P for Punjab, A for the Afghan States (aka North-West Frontier), K for Kashmir, S for Sindh, and Tan for Balochistan. A prominent early proponent for the creation of a Muslim state was Allama Iqbal.

Different conceptions of Pakistan varied widely: some people thought it would be a pan-Asian Muslim superstate, including Central and West Asia. Some viewed it as a state-within-a-state, a Muslim partner to a hypothetical Hindustan within a federated India, and some viewed it as it as a separate sovereign state. These concepts are commonly grouped under the so-called "Two Nation Theory".

On March 23, 1940, Muhammed Ali Jinnah, leader of the All India Muslim League, formally endorsed the "Lahore Resolution," calling for the creation of an independent state in regions where Muslims constituted a majority. At the end of World War II, the United Kingdom moved with increasing urgency to grant India independence. However, the Congress Party and the Muslim League could not agree on the terms for a constitution or establishing an interim government. In June 1947, the British Government declared that it would bestow full dominion status upon two successor states -- India and Pakistan. Under this arrangement, the various princely states could freely join either India or Pakistan. Consequently, a bisected Muslim nation separated by more than 1,600 kilometers (1,000 mi.) of Indian territory emerged when Pakistan became a self-governing dominion within the Commonwealth on August 14, 1947. West Pakistan comprised the contiguous Muslim-majority districts of present-day Pakistan; East Pakistan consisted of a single province, which is now Bangladesh.

The Maharaja of Kashmir was reluctant to make a decision on accession to either Pakistan or India. However, armed incursions into the state by tribesman from the Northwest Frontier Province (NWFP) led him to seek military assistance from India. The Maharaja signed accession papers in October 1947 and allowed Indian troops into much of the state. The Government of Pakistan, however, refused to recognize the accession and campaigned to reverse the decision. The status of Kashmir has remained in dispute.

When the United Kingdom left India in 1947, Pakistan split from India to form a separate Muslim country. From 1947 through 1971 the state consisted of West Pakistan and East Pakistan, separated from one another by India.

Post Independence Period

With the death in 1948 of its first leader and governor-general, Muhammed Ali Jinnah, and the assassination in 1951 of its first Prime Minister, Liaqat Ali Khan, political instability and economic difficulty became prominent features of post-independence Pakistan. Pakistan then became the first Islamic republic on March 23, 1956 with the signing of a new constitution. On October 7, 1958, President Iskander Mirza, with the support of the army, suspended the 1956 constitution, imposed martial law, and canceled the elections scheduled for January 1959. Twenty days later the military sent Mirza into exile in Britain and Gen. Mohammad Ayub Khan assumed control of a military dictatorship. After Pakistan's perceived loss in the Indo-Pakistani War of 1965, Ayub Khan's power declined. Subsequent political and economic grievances inspired agitation movements that compelled his resignation in March 1969. He handed over responsibility for governing to the Commander-in-Chief of the Army, General Agha Mohammed Yahya Khan, who became President and Chief Martial Law Administrator.

1971 Civil War

General elections held in December 1970 polarized relations between the eastern and western sections of Pakistan. Though Muslim, the ethnic composition of the former East Pakistan, consisting mostly people of Bengali origin, differed from that of West Pakistan. The government of Pakistan before 1971 was dominated by West Pakistan, with the East Pakistanis considering themselves discriminated against in government. The Awami League, which advocated autonomy for the more populous East Pakistan, swept the East Pakistan seats to gain a majority in Pakistan as a whole. The Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP), founded and led by Ayub Khan's former Foreign Minister, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, won a majority of the seats in West Pakistan, but the country was completely split with neither major party having any support in the other area. Negotiations to form a coalition government broke down. Consequently, East Pakistan demanded independence, which led to civil war, also referred to as Bangladesh Liberation War in 1971. In that war, troops of West Pakistan, under Yahya Khan, killed an estimated 1.5 million people in an attempt to subdue the rebellion (some other estimates put the number as 3 million). On December 6, 1971, India declared war on Pakistan and a joint Indian Army-Mukti Bahini coalition force captured Dhaka in December 16 1971, resulting in the emergence of the independent State of Bangladesh. Indian involvement in East Pakistan also led to fighting in West Pakistan and Kashmir, and this entire conflict was the third war between the two nations, the Indo-Pakistani War of 1971.

Follwing the war, Yahya Khan then resigned the presidency and handed over leadership of the western part of Pakistan to Bhutto, who became President and the first civilian Chief Martial Law Administrator.

Bhutto moved decisively to restore national confidence and pursued an active foreign policy, taking a leading role in Islamic and Third World forums. Although Pakistan did not formally join the non-aligned movement until 1979, the position of the Bhutto government coincided largely with that of the non-aligned nations. Domestically, Bhutto pursued a populist agenda and nationalized major industries and the banking system. In 1973, he promulgated a new constitution accepted by most political elements and relinquished the presidency to become Prime Minister. Although Bhutto continued his populist and socialist rhetoric, he increasingly relied on Pakistan's urban industrialists and rural landlords. Over time the economy stagnated, largely as a result of the dislocation and uncertainty produced by Bhutto's frequently changing economic policies. When Bhutto proclaimed his own victory in the March 1977 national elections, the opposition Pakistan National Alliance (PNA) denounced the results as fraudulent and demanded new elections. Bhutto resisted and later arrested the PNA leadership.

1977-1985 Martial Law

With increasing anti-government unrest, the army grew restive. On July 5, 1977, the military removed Bhutto from power and arrested him, declared martial law, and suspended portions of the 1973 constitution. Chief of Army Staff General Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq became Chief Martial Law Administrator and promised to hold new elections within three months.

Zia released Bhutto and asserted that he could contest new elections scheduled for October 1977. However, after it became clear that Bhutto's popularity had survived his government, Zia postponed the elections and began criminal investigations of the senior PPP leadership. Subsequently, Bhutto was convicted and sentenced to death for alleged conspiracy to murder a political opponent. Despite international appeals on his behalf, Bhutto was hanged on April 6, 1979.

Zia assumed the Presidency and called for elections in November. However, fearful of a PPP victory, Zia banned political activity in October 1979 and postponed national elections.

In 1980, most center and left parties, led by the PPP, formed the Movement for the Restoration of Democracy (MRD). The MRD demanded Zia's resignation, an end to martial law, new elections, and restoration of the constitution as it existed before Zia's takeover. In early December 1984, President Zia proclaimed a national referendum for December 19 on his "Islamization" program. He implicitly linked approval of "Islamization" with a mandate for his continued presidency. Zia's opponents, led by the MRD, boycotted the elections. When the government claimed a 63% turnout, with more than 90% approving the referendum, many observers questioned these figures.

On March 3, 1985, President Zia proclaimed constitutional changes designed to increase the power of the President vis-a-vis the Prime Minister (under the 1973 constitution the President had been mainly a figurehead). Subsequently, Zia nominated Muhammad Khan Junejo, a Muslim League member, as Prime Minister. The new National Assembly unanimously endorsed Junejo as Prime Minister and, in October 1985, passed Zia's proposed eighth amendment to the constitution, legitimizing the actions of the martial law government, exempting them from judicial review (including decisions of the military courts), and enhancing the powers of the President.

The Democratic Interregnum

On December 30, 1985, President Zia removed martial law and restored the fundamental rights safeguarded under the constitution. He also lifted the Bhutto government's declaration of emergency powers. The first months of 1986 witnessed a rebirth of political activity throughout Pakistan. All parties -- including those continuing to deny the legitimacy of the Zia/Junejo government -- were permitted to organize and hold rallies. In April 1986, PPP leader Benazir Bhutto, daughter of Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto, returned to Pakistan from exile in Europe.

Following the lifting of martial law, the increasing political independence of Prime Minister Junejo and his differences with Zia over Afghan policy resulted in tensions between them. On May 29, 1988, President Zia dismissed the Junejo government and called for November elections. In June, Zia proclaimed the supremacy in Pakistan of Shari'a (Islamic law), by which all civil law had to conform to traditional Muslim edicts.

On August 17, a plane carrying President Zia, American Ambassador Arnold Raphel, U.S. Brig. General Herbert Wassom, and 28 Pakistani military officers crashed on a return flight from a military equipment trial near Bahawalpur, killing all of its occupants. In accordance with the constitution, Chairman of the Senate Ghulam Ishaq Khan became Acting President and announced that elections scheduled for November 1988 would take place.

After winning 93 of the 205 National Assembly seats contested, the PPP, under the leadership of Benazir Bhutto, formed a coalition government with several smaller parties, including the Muhajir Qaumi Movement (MQM). The Islamic Democratic Alliance (IJI), a multi-party coalition led by the PML and including religious right parties such as the Jamaat-i-Islami (JI), won 55 National Assembly seats.

Differing interpretations of constitutional authority, debates over the powers of the central government relative to those of the provinces, and the antagonistic relationship between the Bhutto Administration and opposition governments in Punjab and Balochistan seriously impeded social and economic reform programs. Ethnic conflict, primarily in Sindh province, exacerbated these problems. A fragmentation in the governing coalition and the military's reluctance to support an apparently ineffectual and corrupt government were accompanied by a significant deterioration in law and order.

In August 1990, President Khan, citing his powers under the eighth amendment to the constitution, dismissed the Bhutto government and dissolved the national and provincial assemblies. New elections, held in October of 1990, confirmed the political ascendancy of the IJI. In addition to a two-thirds majority in the National Assembly, the alliance acquired control of all four provincial parliaments and enjoyed the support of the military and of President Khan. Muhammad Nawaz Sharif, as leader of the PML, the most prominent Party in the IJI, was elected Prime Minister by the National Assembly.

Sharif emerged as the most secure and powerful Pakistani Prime Minister since the mid-1970s. Under his rule, the IJI achieved several important political victories. The implementation of Sharif's economic reform program, involving privatization, deregulation, and encouragement of private sector economic growth, greatly improved Pakistan's economic performance and business climate. The passage into law in May 1991 of a Shari'a bill, providing for widespread Islamization, legitimized the IJI government among much of Pakistani society.

After PML President Junejo's death in March 1993, Sharif loyalists unilaterally nominated him as the next party leader. Consequently, the PML divided into the PML Nawaz (PML/N) group, loyal to the Prime Minister, and the PML Junejo group (PML/J), supportive of Hamid Nasir Chatta, the President of the PML/J group.

However, Nawaz Sharif was not able to reconcile the different objectives of the IJI's constituent parties. The largest religious party, Jamaat-i-Islami (JI), abandoned the alliance because of its perception of PML hegemony. The regime was weakened further by the military's suppression of the MQM, which had entered into a coalition with the IJI to contain PPP influence, and allegations of corruption directed at Nawaz Sharif. In April 1993, President Khan, citing "maladministration, corruption, and nepotism" and espousal of political violence, dismissed the Sharif government, but the following month the Pakistan Supreme Court reinstated the National Assembly and the Nawaz Sharif government. Continued tensions between Sharif and Khan resulted in governmental gridlock and the Chief of Army Staff brokered an arrangement under which both the President and the Prime Minister resigned their offices in July 1993.

An interim government, headed by Moeen Qureshi, a former World Bank Vice President, took office with a mandate to hold national and provincial parliamentary elections in October. Despite its brief term, the Qureshi government adopted political, economic, and social reforms that generated considerable domestic support and foreign admiration.

In the October 1993 elections, the PPP won a plurality of seats in the National Assembly and Benazir Bhutto was asked to form a government. However, because it did not acquire a majority in the National Assembly, the PPP's control of the government depended upon the continued support of numerous independent parties, particularly the PML/J. The unfavorable circumstances surrounding PPP rule -- the imperative of preserving a coalition government, the formidable opposition of Nawaz Sharif's PML/N movement, and the insecure provincial administrations -- presented significant difficulties for the government of Prime Minister Bhutto. However, the election of Prime Minister Bhutto's close associate, Farooq Leghari, as President in November 1993 gave her a stronger power base.

In November 1996, President Leghari dismissed the Bhutto government, charging it with corruption, mismanagement of the economy, and implication in extra-judicial killings in Karachi. Elections in February 1997 resulted in an overwhelming victory for the PML/Nawaz, and President Leghari called upon Nawaz Sharif to form a government. In March 1997, with the unanimous support of the National Assembly, Sharif amended the constitution, stripping the President of the power to dismiss the government and making his power to appoint military service chiefs and provincial governors contingent on the "advice" of the Prime Minister. Another amendment prohibited elected members from "floor crossing" or voting against party lines. The Sharif government engaged in a protracted dispute with the judiciary, culminating in the storming of the Supreme Court by ruling party loyalists and the engineered dismissal of the Chief Justice and the resignation of President Leghari in December 1997. The new President elected by Parliament, Rafiq Tarar, was a close associate of the Prime Minister. A one-sided accountability campaign was used to target opposition politicians and critics of the regime. Similarly, the government moved to restrict press criticism and ordered the arrest and beating of prominent journalists. As domestic criticism of Sharif's administration intensified, Sharif attempted to replace Chief of Army Staff General Pervez Musharraf on October 12, 1999, with a family loyalist, Director General ISI Lt. Gen. Ziauddin. Although General Musharraf was out of the country at the time, the Army moved quickly to depose Sharif.

Return of Military Rule

On October 14, 1999, General Musharraf declared a state of emergency and issued the Provisional Constitutional Order (PCO) which suspended the federal and provincial parliaments, held the constitution in abeyance and designated Musharraf as Chief Executive. While delivering an ambitious seven-point reform agenda, Musharraf did not provide a timeline for a return to civilian democratic rule. Musharraf appointed a National Security Council, with mixed military/civilian appointees, a civilian Cabinet, and a National Reconstruction Bureau (think tank) to formulate structural reforms. A National Accountability Bureau (NAB), headed by an active duty military officer was appointed to prosecute those accused of willful default on bank loans and corrupt practices, with convictions resulting in disqualification from political office for twenty-one years. The NAB Ordinance attracted criticism for holding the accused without charge and, in some instances, access to legal counsel. While military trial courts were not established, on January 26, 2000, the government stipulated that Supreme, High, and Shari'a Court justices should swear allegiance to the Provisional Constitutional Order and the Chief Executive. Approximately 85 percent of justices acquiesced, but a handful of justices were not invited to take the oath and were forcibly retired. Political parties were not banned, but a couple of dozen ruling party members remained detained, with Sharif and five colleagues facing charges of attempted hijacking.

Kashmir

A dispute over the state of Kashmir has been ongoing ever since the separation from India. This dispute has led to war on three occasions, including the 1971 war. In response to Indian nuclear weapons testing, Pakistan conducted its own nuclear tests and on April 6, 1998 the nation tested a medium-range missile capable of delivering a nuclear warhead to India. Then on May 28 of the same year Pakistan responded to a series of Indian nuclear tests with five tests of its own, prompting the United States, Japan, and other nations to impose economic sanctions.

The following year saw the breakout of a conflict between the two states in the Kargil Conflict. The conflict arose due to advances made in Kashmir by Pakistani regular and irregular troops. The positions taken by these forces threatened Indian supply lines in Kashmir and lead to an Indian response. Tensions between the two nations would reach alarming heights, but following diplomatic pressure from the United States, Pakistan was forced to retreat from the land it had taken.

Tensions again grew high in 2002 following an attack on the Indian parliament by militants that were believed to have been trained by Pakistan.

However, the following year led to a decrease in tensions amid meetings between high-level Pakistani and Indian officials. 2004 brought meetings between Prime Ministers of both nations, and hopes are high that the Kashmir conflict will reach a resolution soon. Nevertheless, history has proven this to be an exceedingly elusive goal.

See also: Pakistan, Bangladesh, Kashmir, Kargil Conflict

External Links

Story of Pakistan (http://www.storyofpakistan.com)

Pakistan on Encarta (http://encarta.msn.com/encyclopedia_761560851_1/Pakistan.html)fr:Histoire du Pakistan