Galicia (Central Europe)

|

|

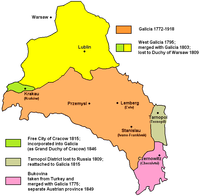

The Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria, or simply Galicia, was the largest and northernmost province of Austria from 1772 until 1918, with Lemberg (Lwów, L'viv) as its capital city. It was created from the territories taken from the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth during the partitions of Poland and lasted until the dissolution of Austria-Hungary at the end of the First World War. Today, Galicia is an historical region split between Poland and Ukraine.

| Contents |

Origin and variations of the name

The name Galicia et Lodomeria was first used in the 13th century by King Andrew II of Hungary. It was a Latinized version of the Slavic names Halych and Volodymyr, the major cities of the Ruthenian principality of Halych-Volhynia, which was under Hungarian rule at the time.

The origin of the Ukrainian name Halych (Halicz in Polish, Galich in Russian, Galic in Latin) is uncertain. Some historians believe it is of Celtic origin, and related to many similar place names found across Europe, such as Galaţi in Romania, Gaul (France), Galicia in Spain, and Wales in Britain. Others claim that the name is of Slavic origin – either from halytsa/galitsa meaning "a naked (unwooded) hill", or from halka/galka which means "a jackdaw". The jackdaw was used as a charge in the city's coat-of-arms and later also in the coat-of-arms of Galicia. The name, however, predates the coat-of-arms which may represent folk etymology.

Although Hungarians were driven out from Halych-Volhynia by 1221, Hungarian kings continued to add Galicia et Lodomeria to their official titles. In the 17th century, those titles were inherited, together with the Hungarian crown, by the Habsburgs. In 1772, Empress Maria Theresa, Archduchess of Austria and Queen of Hungary, decided to use those historical claims to justify her participation in the first partition of Poland. In fact, the territories acquired by Austria did not correspond exactly to those of former Halych-Volhynia. Volhynia, including the city of Włodzimierz Wołyński (Volodymyr Volyns'kyi)—after which Lodomeria was named—was taken by Russia, not Austria. On the other hand, much of Lesser Poland—which was historically and ethnically Polish, not Ruthenian—did become part of Galicia. Moreover, despite the fact that the claim derived from the historical Hungarian crown, Galicia and Lodomeria was not officially assigned to Hungary, and after the Ausgleich of 1867, it found itself in Cisleithania, or the Austrian part of Austria-Hungary.

The full official name of the new Austrian province was:

After the incorporation of the Free City of Kraków in 1846, it was extended to:

- Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria, and the Grand Duchy of Krakau with the Duchies of Auschwitz and Zator.

Each of those entities was formally separate; they were listed as such in the Austrian emperor's titles, each had its distinct coat-of-arms and flag. For administrative purposes, however, they formed a single province. The duchies of Auschwitz (Oświęcim) and Zator were small historical principalities west of Kraków, on the border with Prussian Silesia. Lodomeria existed only on paper; it had no territory and could not be found on any map.

Galicia and Lodomeria in different languages

- Latin: Galicia et Lodomeria

- German: Galizien und Lodomerien

- Hungarian: Gácsország és Lodoméria

- Polish: Galicja i Lodomeria

- Slovak: Halič a Vladimírsko or Galícia a Lodoméria

- Ukrainian: Halychyna i Volodymyria (Галичина і Володимирія)

History

Prior to partitions of Poland

The region of what later became known as Galicia appears to have been incorporated, in large part, into the Empire of Great Moravia. It appears in an historical reference 981, when the ruler of Kievan Rus' took over the Red Ruthenia (Cherven' Rus') cities in his military campaign on the border with Poland. In the following century, the area shifted briefly to Poland (1018-1031) and then back to Ruthenia. As the successor state to Kievan-Rus', the Principality of Halych (Halychyna) existed from 1087 to 1253, united with Volhynia in the state of Halych-Volynia from around 1200. It was a vassal kingdom of the Mongol Golden Horde from 1253 to 1340. During this time, the princes of Halych-Volhynia moved the capital from Halych to L'viv. They also attempted to gain papal and broader support in Europe for an alliance against the Mongols. Their efforts were rewarded by papal acclamation of the prince of Halich-Volynia as the "King of Rus'", an era which came to an end around 1340-1349, when King Casimir III of Poland conquered the region. The sister state of Volynia, together with Kyiv, then fell under Lithuanian control and the mantle of Rus' was transferred from Halych-Volynia to Lithuania.

- See also: Red Ruthenia and Halych-Volhynia.

Thereafter, the region comprised a Polish possession divided into a number of voivodships. This began an era of heavy Polish settlement among the Ruthenian population. Armenian and Jewish emigration to the region also occurred in large numbers. Numerous castles were built during this time and some new cities were founded: Stanisławów (now Ivano-Frankivsk) and Krystynopol (now Chervonohrad).

From partitions of Poland to the Congress of Vienna

In 1772, Galicia became the largest part of the area annexed by Austria in the First Partition. As such, the Austrian region of Poland and Ukraine was known as the Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria to underline the Hungarian claims to the country. However, a large portion of Little Poland was also added to the province, which changed the geographical reference of the term, Galicia. L'viv—Lemberg—served as the capital of Austrian Galicia, which was dominated by the Polish aristocracy, despite the fact that the population of the eastern half of the province was in the majority Ruthenian or Ukrainian with large minorities of Jews and Poles. The Poles were also overwhelmingly more numerous in the newly-added western half of Galicia.

- More to be written.

From 1815 to 1860

In 1846, the former Polish capital city of Cracow became part of the province following the Austrian suppression of that independent republic.

- More to be written.

Galician autonomy

Following the Battle of Sadova and the Austrian defeat in the Austro-Prussian War, the Austrian empire began to tremble. Politically and militarily defeated, the empire was also experiencing internal problems. In an effort to shore up support for the monarchy, Emperor Franz Joseph began negotiations for a compromise with the Magyar nobility to ensure their support. Some members of the government, such as Austrian prime minister Count Belcredi, advised the Emperor to make a more comprehensive constitutional deal with all of the nationalities that would have created a federal structure. Belcredi worried that an accommodation with the Magyar interests would alienate the other nationalities. However, Franz Joseph was unable to ignore the power of the Magyar nobility, and they would not accept anything less than dualism between themselves and the traditional Austrian élites.

Finally, after the so-called Ausgleich of February of 1867, the Austrian Empire was reformed into a dualist Austria-Hungary. Although the Polish and Czech plans for their parts of the monarchy to be included in the federal structure failed, a slow yet steady process of liberalisation of Austrian rule in Galicia started. This was aided by a large part of the Poles inhabitating the area, who were dissatisfied with extreme poverty and the failure of the romantic January Uprising. The prominent Polish politicians and members of the intelligentsia adressed the Emperor asking for greater authonomy of Galicia. Their plea was accepted and in 1867 the region was granted its own parliament located in Lwów. Until 1871 a completely new political structure of the area was formed.

From 1868 Galicia was an autonomous province of Austria-Hungary with Polish as an official language. The Germanisation was halted and soon afterwards the censorship was halted as well. Galicia was subject to the Austrian part of the Dual Monarchy, but the Galician Sejm had increasingly more privileges and prerogatives. Until 1871 it was responsible for education, taxation, culture and construction efforts. It was also entitled to send its deputies to the Austrian parliament in Vienna, with full rights of members of the parliament.

The positive changes were supported by many Galician intellectuals. In 1869 a group of young conservative publicists, including Józef Szujski, Stanisław Tarnowski, Stanisław Koźmian and Ludwik Wodzicki, published a series of satirical pamphlets entitled Teka Stańczyka (Stańczyk's Portfolio). Only five years after the tragic end of the January Uprising, the pamphlets ridiculed the idea of armed national uprisings and suggested a compromise with Poland's enemies, especially the Austrian Empire, and more concentration on economic growth. The basic conclusion was that Poles are generally unable to think of themselves as a state rather than a nation and that increasing the authonomy instead of senseless armed struggles would teach the nation how to govern itself.

First World War and Polish-Ukrainian conflict

During the First World War Galicia saw heavy fighting between the forces of Russia and the Central Powers. The Russian forces overran most of the region in 1914 after defeating the Austro-Hungarian army in a chaotic frontier battle in the opening months of the war. They were in turn pushed out in the spring and summer of 1915 by a combined German and Austro-Hungarian offensive.

In 1918, Western Galicia became a part of the restored Republic of Poland, while the local Ukrainian population briefly declared the independence of Eastern Galicia as the "Western Ukrainian Republic". During the Polish-Soviet War a short-lived Galician SSR in East Galicia existed. Eventually, the whole of the province was recaptured by Poles. Poland's annexation of Eastern Galicia was internationally recognized in 1923.

- More to be written.

Second World War and Distrikt Galizien

After the Nazi-Soviet pact, Stalin annexed Eastern Galicia to the Soviet Republic of Ukraine. Germany occupied it in 1941 and incorporated it into the General Government as Distrikt Galizien.

- More to be written.

Legacy

The border was later recognized by the Allies in 1945, and the region was ethnically cleansed by Soviets and a communist Polish government (Wisla Action). The old province, as modified by Austria around 1800, remains divided today, with the western part Polish, and the original eastern part, Ukrainian.

- More to be written.

Economy

Despite being one of the most populous regions in Europe, Galicia was also one of the least developed economically. The first detailed description of the economic situation of the region was prepared by Stanislaw Szczepanowski (1846-1900), a Polish lawyer, economist and chemist who in 1873 published the first version of his report titled Nędza galicyjska w cyfrach (The Galician Poverty in Numbers). Based on his own experience as a worker in the India Office, as well as his work on development of the oil industry in the region of Borysław and the official census data published by the Austro-Hungarian government, he described Galicia as one of the poorest regions in Europe.

In 1888 Galicia had 785,500 km² of area and was populated by ca. 6,4 million of people, including 4,8 million peasants (75% of the whole population). The population density was 81 people per square kilometre and was higher than in France (71 inhabitants/km²) or Germany.

The average life expectantcy was 27 years for men and 28,5 years for women, as compared to 33 and 37 in Bohemia, 39 and 41 in France and 40 and 42 in England. Also the quality of life was much lower. The yearly consumption of meat did not exceed 10 kilograms per capita, as compared to 24 kg in Hungary and 33 in Germany. This was mostly due to much lower average income.

The average income per capita did not exceed 53 Rhine guilders, as compared to 91 RG in the Kingdom of Poland, 100 in Hungary and more than 450 RG in England at that time. Also the taxes were relatively high and equalled to 9 Rhine guilders a year (ca. 17% of yearly income), as compared to 5% in Prussia and 10% in England. Also the percentage of people with higher income was much lower than in other parts of the Monarchy and Europe: the luxury tax, paid by people whose yearly income exceeded 600 RG, was paid by 8 people in every 1000 inhabitants, as compared to 28 in Bohemia and 99 in Lower Austria. Despite high taxation, the national debt of the Galician government exceeded 300 million RG at all times, that is approximately 60 RG per capita.

All in all, the region was used by the Austro-Hungarian government mostly as a reservoir of cheap workforce and recruits for the army, as well as a buffer zone against Russia. It was not until early in the 20th century that heavy industry started to be developed, and even then it was mostly connected to war production. The biggest state investments in the region were the railways and the fortresses in Przemyśl, Kraków and other cities. Industrial development was mostly connected to the private oil industry started by Ignacy Łukasiewicz and to the Wieliczka salt mines, operational since at least the Middle Ages.

Principal cities

- L'viv (Львів, formerly Lwów, Lvov, Lemberg, Leopolis)

- Kraków

- Przemyśl (Перемишль (Peremyshl') in Ukrainian)

- Ivano-Frankivs'k (Івано-Франківськ, formerly Stanisławów)

See also

Reference

- Taylor, A.J.P., The Habsburg Monarchy 1809-1918 1941, discusses Habsburg policy toward ethnic minorities.

External links

- Old map of Galicia (http://www.ceti.pl/~piwkowsk/locations/galicja/galicja.html)cs:HaliÄŤ

de:Galizien (Ukraine) es:Galicia (Europa Central) et:Galiitsia he:גליציה nl:Galicië (Oost-Europa) no:Galicia og Lodomeria pl:Galicja (zabór) pt:Galiza (Europa de Leste) ro:Galiţia sk:Halič (región) sv:Galizien uk:Галичина