Ebola

|

|

| Ebola virus | |

|---|---|

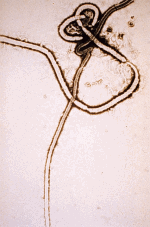

An electron micrograph showing the filamentous structure of the viral particle. The filaments are 60-80 nm in diameter. Template:Taxobox begin placement virus Template:Taxobox group v entry | |

| Order: | Mononegavirales |

| Family: | Filoviridae |

| Genus: | Ebolavirus |

|- style="text-align:center; background:violet;"

!Species

|-

| style="padding: 0 .5em;" |

Ivory Coast ebolavirus

Reston ebolavirus

Sudan ebolavirus

Zaire virus

|}

Ebola hemorrhagic fever (alternatively Ebola Haemorrhagic Fever, EHF, or just Ebola) is a very rare, but severe, often fatal infectious disease occurring in humans and other primates, caused by the Ebola virus.

The Ebola virus was first discovered in 1976. Epidemics with 50 to 90% mortality have occurred in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Gabon, Uganda and Sudan.

| Contents |

|

|

The Ebola virus

The virus comes from the Filoviridae family, of which the Marburg virus is also a member. It is named after the Ebola River in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (formerly Zaire), near the first epidemics.

It is traditional to name viral strains (subtypes) after the locations where they were first discovered. Two strains were identified in 1976: Ebola–Zaïre (EBO–Z) and Ebola–Sudan (EBO–S) with average mortality rates of 83% and 54% respectively. A third strain, Ebola–Reston, was discovered in November 1989 in a group of monkeys (Macaca fascicularis) imported from the Philippines to the Hazleton Primate Quarantine Unit in Reston, Virginia (US).

Further outbreaks have occurred in Zaire/Democratic Republic of the Congo (1995 and 2003), Gabon (1994, 1995 and 1996), Uganda (2000), and Sudan again (2004). A new subtype was identified from a single human case in the Côte d'Ivoire in 1994, EBO–CI. In 2003, 120 people died in Etoumbi, Republic of Congo, which has been the site of four recent outbreaks, including one in May 2005.

Of the approximate 1,500 identified Ebola cases worldwide, two-thirds of the patients have died. The animal/arthropod reservoir which sustains the virus between outbreaks has not been identified.

Structure

Electron micrographs of the Ebola virus show it to have the characteristic filamentous structure of a filovirus. The viral filaments can appear in images in various shapes including a "U", "6", a coil, or may be branched. The filaments are reported to be between 60–80 nm in diameter; the length of a filament associated with an individual viral particle is extremely variable, with Ebola particles of up to 14,000 nm in length being reported. An average length, which may represent the most infectious particles, is in the region of 1,000 nm. The first electronmicrograph of Ebola was obtained on 13 October, 1976 by Dr. F.A. Murphy, now at the University of California, Davis, who was then working at the CDC. The nucleocapsid structure consists of a central channel, 20–30 nm in diameter, surrounded by helically wound capsid with a diameter of 40–50 nm and an interval of 5 nm. Seven nm glycoprotein spikes that are 10 nm apart from each other are present within the outer envelope of the virus, which is derived from the host cell membrane. Each viral particle contains one molecule of single-stranded, negative-sense RNA, which encodes the seven viral proteins.

7042_lores-Ebola-Zaire-CDC_Photo.jpg

Georg

Ebola virus history

Ebola–Zaïre

Ebola Zaïre, the first-discovered Ebola strain, is also the most deadly with up to a 90% average mortality per epidemic. There have been more outbreaks of Ebola Zaïre than any other strain. The first outbreak took place on August 26th, 1976 in Yambuku, a town in northern Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo). The first recorded case (NOTE: not the index case) was a Mabalo Lokela, a 44 year old school teacher just returning from a trip around Northern Zaire, who was examined at a hospital run by Belgian nuns. His high fever was diagnosed as possible Malaria and he was given a quinine shot. Lokela returned to the hospital every day. A week later his symptoms included uncontrolled vomiting, severe diarrhea, headache, dizziness, and trouble breathing. Later the bleeding began from his nose, mouth, and rectum. Mabalo Lokela died on September 8th, 1976, roughly 14 days after the onset of symptoms.

And then more patients arrived with varying but similar symptoms: fever, headache, muscle/joint aches, fatigue, nausea, dizziness etc. which often progressed to bloody diarrhea, severe vomiting, and bleeding from the nose, mouth, and rectum. The initial vector of transmission was believed to be the needle used for Lokelas's injection and then reused without sterilization (a common practice in many countries). Followed by transmission due to care of the sick patients without barrier nursing and traditional burial preparations that involve washing and GI tract cleansing.

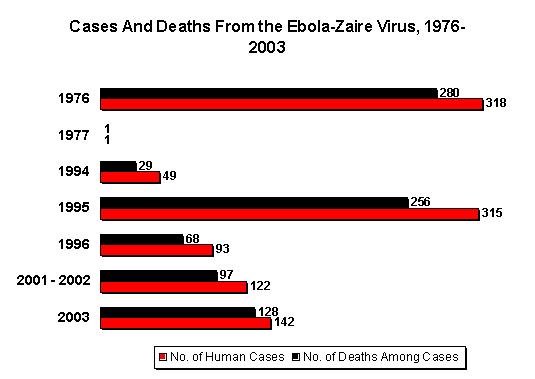

The fatality rates were 88% in 1976, 100% in 1977, 59% in 1994, 81% in 1995, 73% in 1996, 80% in 2001/2002 and 90% in 2003. The average fatality rate for Ebola Zaïre is 82.6%.

Ebola–Sudan

Meanwhile, another outbreak was occurring in the cities of Nzara and Maridi, Sudan. The first case that occurred in Nzara involved a worker who had been exposed to the potential natural reservoir at the local cotton factory. A natural reservoir is a carrier of the virus that is immune to its effects. Although many of the creatures — ranging from spiders to insects to rats and bats — found in the factory were tested for Ebola, none of the tests came back testing positive (Draper 30–31). The natural reservoir for Ebola is still unknown today (Fact Sheet No. 103).

Another case was the death of a nightclub owner in Nzara who could afford to go to the fancier hospital located in Maridi. Unfortunately, the nurses there also did not properly sterilize their needles, and the hospital, like the one in Yambuku, became a breeding ground for new Ebola cases (Draper 30–31). Several epidemics of Ebola–Zaïre and Ebola–Sudan have occurred since 1976.

The most recent outbreak of Ebola–Sudan occurred in May 2004. As of May 24, 2004, 20 cases (including five deaths) of Ebola–Sudan were reported in Yambio County, Sudan. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention confirmed the virus a few days later. The neighboring countries of Uganda and the Democratic Republic of Congo have increased surveillance in bordering areas, and other similar measures have been taken to control the outbreak.

The fatality rates for Ebola Sudan are 53% in 1976, 68% in 1979, and 53% in 2000/2001. The average fatality rate is 53.76%.

Ebola–Reston

This strain was discovered in November of 1989 in a group of 100 cynomolgus macaque monkeys (Macaca fascicularis) imported from Ferlite Farms in Mindanao, Philippines to Hazleton Research Products Primate Quarantine Unit in Reston, Virginia, about 10 miles from Washington DC. A parallel infected shipment was also sent to Philadelphia. There was evidence to support airborne (aerosol) transmission. This strain was highly lethal in monkeys, but did not cause any illness in humans. Six of the Reston primate handlers tested positive (2 due to previous exposure) for the virus, but none became ill. Further Ebola Reston infected monkeys were shipped to Hazleton facilities in both Reston Virginia and Alice Texas (Hazleton's Texas Primate Center) in February of 1990. More EBO-R infected monkeys were discovered in 1992 in Siena, Italy and at the Texas Hazleton facility again in March 1996. There was a high rate of co-infection with Simian Hemorrhagic Fever (SHF) in all of these EBO-R infected monkeys. No human illness has resulted from any of these outbreaks.

Ebola–Côte d'Ivoire

In 1994, a scientist became ill after conducting an autopsy on a wild chimpanzee. The scientist recovered6. Not much is known about this form of Ebola since only one case of it has been discovered.

Ebola hemorrhagic fever

Among humans, the virus is transmitted by direct contact with infected body fluids such as blood. The incubation period is 2 to 21 days. Symptoms are variable and often appear suddenly. Initial symptoms include: high fever (at least 101°F), severe headache, muscle/joint/abdominal pain, severe weakness and exhuastion, sore throat, nausea, and dizziness. Before an epidemic is suspected, these early symptoms are easily mistaken for malaria, typhoid fever, dysentery, or various bacterial infections, which are all far more common. The secondary symptoms often involve bleeding both internally and externally from any opening in the body. Dark or bloody stools and diarrhea, vomiting blood, red eyes from swollen blood vessels, red spots on the skin from subcutaneous bleeding, and bleeding from the nose, mouth, rectum, genitals and needle puncture sites. Other secondary symptoms include low blood pressure (less than 90mm Hg) and a fast but weak pulse, eventual organ damage including the kidney and liver by co-localized necrosis, and proteinuria (the presence of proteins in urine). From onset of symptoms to death (from shock due to blood loss or organ failure) is usually between 7 and 14 days .

Transmission

Ebola is one of the rarest human diseases known. Based on the limited number of cases seen to date, it is difficult to be certain of all possible routes of transmission.

Although easy to demonstrate in laboratory conditions with monkeys16,17,18, there has never been a documented case of airborne transmission in human epidemics. Nurse Mayinga may represent the only possible case. The means by which she contracted the virus remains uncertain.

So far all epidemics of Ebola have occurred in sub-optimal hospital conditions, where practices of basic hygiene and sanitation are often either luxuries or unknown to caretakers and where disposable needles and autoclaves are unavailable or too expensive. In modern hospitals with disposable needles and knowledge of basic hygiene and barrier nursing techniques (mask, gown, gloves), Ebola rarely spreads on such a large scale.

In the early stages, Ebola may not be highly contagious. As illness progresses, bodily fluids from diarrhea, vomiting, and bleeding represent an extreme biohazard. Due to lack of proper equipment and hygienic practices, large scale epidemics are mostly problematic in poor, isolated areas without modern hospitals and/or well-educated medical staff. Many areas where the infectious reservoir exists have just these characteristics. In such environments all that can be done is to immediately cease all needle sharing or use without adequate sterilization procedures, to isolate patients, and to observe strict barrier nursing procedures with the use of a N95/P95/P100 or medical rated disposable face mask, gloves, (if possible) googles, and gown at all times. This should be strictly enforced for all medical personnel and visitors.

Vaccines

Recent efforts1,15 have produced vaccines for both Ebola and Marburg that are 100% effective in protecting a group of monkeys from the disease. Recent tests were conducted at USAMRIID in collaboration with Canada's National Microbiology Laboratory in Winnipeg. A dutch company Crucell has also announced a successful tests of their commercial vaccine in monkeys. No human testing has yet been announced for any of these filovirus vaccines. Earlier vaccine efforts, like the one at NAIAD14 in 2003 that was entering human trials have so far not reported any successes.

Treatments

Despite some initial anecdotal evidence to the contrary, blood serum from Ebola survivors has been shown to be ineffective in treating the virus.

In 1999, Maurice Iwu announced at the International Botanical Congress that a fruit extract of Garcinia kola, a West African tree long used by local traditional healers for other illnesses, stopped Ebola virus replication in lab tests. These tests involved cell samples; no animal or human trials had yet been conducted. No further information is available on this as of June 2005.

Economic impact

Ebola has affected tourism in the Democratic Republic of the Congo12, and Uganda (Busharizi). The cost to transport laboratory monkeys has tripled in some locations. 12.

Bioterrorism

Airborne transmission of Ebola Zaire has been demonstrated in monkeys in a controlled laboratory environment at USAMRIID several times in 1995/1996.16,17,18.

In his book Biohazard, former Soviet biological warfare researcher Ken Alibek claimed that the former Soviet Union experimented extensively with use of Ebola as a biological weapon.

The book Executive Orders by Tom Clancy describes an extensive bioterrorist attack on the United States via a newly discovered strain of Ebola (titularly the same strain that killed Mayinga) that propagates by air.

The book Rainbow Six by Tom Clancy describes a group of radical environmentalists who want to rid the world of people, who are destroying the environment. They use a modified version of Ebola that is estimated 99.999% virulent, leaving alive only one person in 10,000 who is infected, and they create a vaccine for the few thousand people who are chosen to live on Earth.

Fiction

This disease has captured the imagination of not only the general public (after it was popularized), but of virologists as well. Some of whom couldn't resist making references to Michael Crichton's 1978 Novel The Andromeda Strain, which describes events in a small Nevada town resulting from a newly discovered virus of extra-terrestial origin, written in a documentary style. The Ebola virus was first popularized by novelist Richard Preston in his medical thriller, The Hot Zone, an exciting novel based on the Ebola outbreaks in Reston, Virginia and Central Africa. The novel is significant because it is very dramatic and yet attempts to portray itself as a factual account of events, which has led to much misunderstanding about this virus from the general public and popular press. It is important to note that, unlike The Andromeda Strain, Preston's novel was placed in the non-fiction section at many bookstores. The Hot Zone remains an excellent example of the kind of pseudo-documentary which Crichton used for dramatic effect in many of his science fiction novels including Jurassic Park, and the more recent Prey. Films have recently followed suit with The Blair Witch Project and Incident at Loch Ness.

Another piece of fictional work that dramatisizes Ebola (in particular, Ebola Zaire Mayinga) is Executive Orders by Tom Clancy. In it, Iranian doctors replicate the virus, which they proved to be airborne. They unleashed the virus on the United States.

Myths

Unfortunately, due to exaggerations in The Hot Zone and probably Hollywood films like Outbreak, it can be difficult for non-virologists to separate fact from fiction. Especially when the popular press compounds the problem by treating a highly dramatized story as if it were real. Among certain biologists/virologists Mr. Preston is not highly regarded. A fifth strain of Ebola known as 'Ebola Preston' has been reported, "which attacks via print and visual media" (Ed Regis), and where "Bricks of bad information and fear-mongering set up a highly-efficient, deadly cycle of hysteria replication in the populace. The public hemorrages, spilling hysteria to the next unwitting victim. Fear gushes from every media orifice. No one is safe from the hype." (Brian Hjelle)

Myth: The virus kills so fast that it has little time to spread. Victims die very soon after contact with the virus.

Reality: The incubation time is actually 2-21 days. That means that you can be walking around with the virus for up to 3 weeks before you show any symptoms at all. The average time from onset of early symptoms to death varies but is often around 8-10 days and sometimes up to 2 weeks. More than long enough to infect many people before you die. Even after contracting a fatal case of Ebola Zaire, you could have up to 5 weeks to live.

Myth: The virus symptoms are horrifying beyond belief. Terrifyingly messy with squirting blood, liquifying flesh, faces like zombies, dramatic projectile bloody vomiting, a human body literally melting into a soup of bloody virus particles.

Reality: We all enjoy reading about that. It sounds exciting and sells lots of books. Preston's next novel is even more gory. But it's just not the reality. Only a tiny fraction of Ebola victims have severe bleeding of a kind that would be even somewhat dramatic to see. Most of the bleeding is subtle, occurring internally. Ebola victims still look like people. They are mainly very tired and are in a great deal of pain with a high fever, horrible headaches and body pains. Sort of like a person with a very bad flu (which people also die of). It is certainly a painful way to die, but it bears little relationship to what was portrayed in The Hot Zone. It's just not that dramatic to watch in real life. At least according to those who actually have watched it. People that would not include Richard Preston.

The following is an excerpt from Ed Regis's interview21 with Philippe Calain, M.D. Chief Epidemiologist, CDC Special Pathogens Branch, Kikwit 1995:

"At the end of the disease the patient does not look, from the outside, as horrible as you can read in some books. They are not melting. They are not full of blood. They're in shock, muscular shock. They are not unconscious, but you would say 'obtunded', dull, quiet, very tired. Very few were hemorrhaging. Hemorrhage is not the main symptom. Less than half of the patients had some kind of hemorrhage. But the ones that bled, died"

See also

- Marburg Hæmorrhagic fever, the first known filovirus disease

- Bolivian hæmorrhagic fever

- Crimean Congo hæmorrhagic fever (CCHF)

External links

- http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/JID/journal/contents/v179nS1.html

- http://www.itg.be/ebola/ebola-06.htm

- http://www.scripps.edu/newsandviews/e_20020114/ebola1.html

- http://www.itg.be/ebola/ebola-12.htm

References

- Vaccines protect monkeys from Ebola, Marburg (http://www.cbc.ca/story/science/national/2005/06/05/monkey-vaccines050605.html). CBC News 5 June 2005

- Breakthrough in Ebola Vaccine (http://news.bbc.co.uk/go/pr/fr/-/2/hi/health/3126365.stm). BBC News World Edition 6 August 2003. 3 September 2003.

- Busharizi, Paul. Ebola Hits Uganda’s Tourism Revival Effort (http://www.planetark.org/dailynewsstory.cfm?newsid=0385). Planet Ark. 27 December 2000. 3 September 2003.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and World Health Organization. Infection for Health Control of Viral Hemorrhagic Fevers in the African Health Care Setting (http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dvrd/spb/mnpages/vhfmanual/entire.pdf). Atlanta, Center for Disease Control and Prevention, 1998. 3 September 2003.

- Draper, Allison Stark. Ebola. New York: The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc., 2002.

- Ebola Hemorrhagic Fever (http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dvrd/spb/mnpages/dispages/ebola.htm). Centers for Disease Control Special Pathogens Branch. 8 September 2003.

- Ebola Hemorrhagic Fever Table Showing Known Cases and Outbreaks, in Chronological Order (http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dvrd/spb/mnpages/dispages/ebotabl.htm). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 18 October 2002. 3 September 2003.

- Fact Sheet Number 103 Ebola Hemorrhagic Fever (http://www.who.int/inf-fs/en/fact103.html). World Health Organization. December 2000. 3 September 2003.

- Filoviruses (http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dvrd/spb/mnpages/dispages/filoviruses.htm). Centers for Disease Control Special Pathogens Branch. 3 September 2003.

- Horowitz, Leonard G. Emerging Viruses: AIDS & Ebola — Nature, Accident, or Intentional?. Rockport, MA: Tetrahedron, Inc., 1996.

- Preston, Richard. The Hot Zone. New York: Anchor Books Doubleday, 1994.

- Russell, Brett. What are the Chances? (http://www.brettrussell.com/personal/what_are_the_chances_.html) Ebola FAQ. 3 September 2003.

- TED Case Study: Ebola and Trade (http://www.american.edu/projects/mandala/TED/ebola.htm). Trade and Environment Databases. May 1997. 7 November 2003.

- Oplinger, Anne A. NIAID Ebola Vaccine Enters Human Trial (http://www2.niaid.nih.gov/newsroom/releases/ebolahumantrial.htm). NIAID: The National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. November 2003. 3 May 2005.

- Live attenuated recombinant vaccine protects nonhuman primates against Ebola and Marburg viruses (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=pubmed&dopt=Abstract&list_uids=15937495&query_hl=9) PubMed 5 June 2005

- Lethal experimental infection of rhesus monkeys with Ebola-Zaire (Mayinga) virus by the oral and conjunctival route of exposure (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=pubmed&dopt=Abstract&list_uids=8712894&query_hl=12) PubMed February 1996 Jaax/Davis/Geisbert/Jahrling

- Transmission of Ebola virus (Zaire strain) to uninfected control monkeys in a biocontainment laboratory (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=pubmed&dopt=Abstract&list_uids=8551825&query_hl=12) PubMed December 1995

- Lethal experimental infections of rhesus monkeys by aerosolized Ebola virus (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=pubmed&dopt=Abstract&list_uids=7547435&query_hl=12) PubMed August 1995

- Marburg and Ebola viruses as aerosol threats (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=pubmed&dopt=Abstract&list_uids=15588056&query_hl=12) PubMed 2004 USAMRIID

- Other viral bioweapons: Ebola and Marburg hemorrhagic fever (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=pubmed&dopt=Abstract&list_uids=15207310&query_hl=12) PubMed 2004

- Regis, Ed. Virus Ground Zero; Simon & Schuster: New York, 1996; p104

ar:ايبولا da:Ebola de:Ebolavirus es:Ébola fr:Ebola ja:エボラ出血熱 ms:Ebola nl:Ebola pl:Wirus Ebola pt:Ébola ru:Геморрагическая лихорадка Эбола simple:Ebola fi:Ebola zh-cn:埃博拉病毒 sv:Ebolafeber