Anglo-Zulu War

|

|

Zulusmall.jpg

The Anglo-Zulu War was fought in 1879 between Britain and the Zulus, and signalled the end of the Zulus as an independent nation. It had complex beginnings, some bad decisions, bloody battles that caused the British to engage earlier than they intended, but played out a common story of British colonialism.

| Contents |

Background

Disputes as to the causes of the war which broke out on January 11, 1879 concerned, chiefly, the occupied territory which in 1854 was proclaimed the republic of Utrecht, and the Boers who had settled there, who had that year obtained a deed of cession from king Mpande. In 1860 a Boer commission was appointed to beacon the boundary, and to obtain from the Zulu, if possible, a road to the sea at St Lucia Bay. However the commission achieved nothing.

In 1861, Umtonga, a brother of Cetshwayo, fled to the Utrecht district, and Cetshwayo assembled an army on that frontier. According to evidence later brought forward by the Boers, Cetshwayo offered the farmers a strip of land along the border if they would surrender his brother. The Boers complied on the condition that Umtonga's life was spared, and in 1861 Mpande signed a deed transferring this land to the Boers. The southern boundary of the land added to Utrecht ran from Rorke's Drift on the Buffalo to a point on the Pongola River.

The boundary was beaconed in 1864, but when in 1865 Umtonga fled from Zululand to Natal, Cetshwayo, seeing that he had lost his part of the bargain (for he feared that Umtonga might be used to supplant him, as Mpande had been used to supplant Dingane), caused the beacon to be removed, and also claimed the land ceded by the Swazis to Lydenburg. The Zulu asserted that the Swazis were their vassals and therefore had no right to part with this territory. During the year a Boer comando under Paul Kruger and an army under Cetshwayo were posted to defend the newly acquired Utrecht border. The Zulu forces took back their land north of the Pongola. Questions were also raised as to the validity of the documents signed by the Zulu concerning the Utrecht strip; in 1869 the services of the lieutenant-governor of Natal were accepted by both parties as arbitrator, but the attempt then made to settle disagreements proved unsuccessful.

Such was the political background when Cetshwayo became absolute ruler of the Zulu position upon his father's death. As ruler, Cetshwayo set about reviving the military methods of his uncle Shaka as far as possible, and even succeeded in equipping his regiments with firearms. It is believed that he caused the Kaffirs in the Transkei to revolt, and he aided Sikukuni in his struggle with the Transvaal. His rule over his own people was tyrannous. For example, Bishop Schreuder (of the Norwegian Missionary Society) described Cetshwayo as "an able man, but for cold, selfish pride, cruelty and untruthfulness, worse than any of his predecessors."

In September 1876 the massacre of a large number of girls (who had married men of their own age instead of men from an older regiment, as ordered by Cetshwayo) provoked a strong protest from the government of Natal (which was itself responsible for tyrannous injustices towards Africans), the occupying governments were usually inclined to look patronisingly upon the affairs of the subjected African nations. The tension between Cetshwayo and the Transvaal over border disputes continued, and when in 1877 Britain annexed the Transvaal, the new occupiers of the country inherited these problems.

The Ultimatum

A commission was appointed by the lieut.-governor of Natal in February 1878 to report on the boundary question. The commission reported in July, and found almost entirely in favour of the contention of the Zulu. Sir Henry Bartle Frere, then High Commissioner, who thought the award one-sided and unfair to the Boers (Martineau, Life of Frere, ii. xix.), stipulated that, on the land being given to the Zulu, the Boers living on it should be compensated if they left, or protected if they remained. Cetshwayo (who now found no defender in Natal save Bishop Colenso) was in a defiant mood, and permitted outrages by Zulu both on the Transvaal and Natal borders.

In 1878, Frere used a minor border incursion — two warriors had fetched two eloped girls from Natal — as a pretext to demand 500 head of cattle from the Zulu as reparations. Cetshwayo only sent £50 worth of gold. When two surveyors were captured in Zululand, Frere demanded more reparations and Cetshwayo again refused. Frere sent emissaries to meet him and tell his demands.

Frere was convinced that the peace of South Africa could be preserved only if the power of Cetshwayo was curtailed. Therefore in forwarding his award on the boundary dispute the High Commissioner demanded that the military system should be remodelled. The youths were to be allowed to marry as they came to man's estate, and the regiments were not to be called up except with the consent of the council of the nation and also of the British government. Moreover, the missionaries were to be unmolested and a British resident was to be accepted. An ultimatum was made to Zulu deputies on December 11th 1878, a definite reply being required by the 31st of that month.

Frere was either very arrogant or wanted to deliberately insult Cetshwayo. If so, he succeeded. Cetshwayo rejected the demands of December 11, by not responding by the end of the year. A concession was granted by the British until January 11, 1879, after which a state of war was deemed to exist.

British invasion

Main articles: Battle of Isandlwana, Rorke's Drift, Siege of Eshowe, Battle of Hlobane and Battle of Kambula

Cetshwayo returned no answer, and in January 1879 a British force under Lieutenant general Frederick Augustus Thesiger, 2nd Baron Chelmsford invaded Zululand. Lord Chelmsford had under him a force of 5000 Europeans and 8200 Africans; 3000 of the latter were employed in guarding the frontier of Natal; another force of 1400 Europeans and 400 Africans were stationed in the Utrecht district. Three columns were to invade Zululand, from the Lower Tugela, Rorke's Drift, and Utrecht respectively, their objective being Ulundi, the royal kraal.

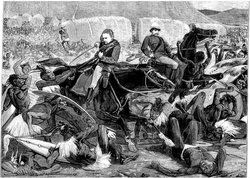

Cetshwayo's army numbered fully 40,000 men. The entry of all three columns was unopposed. On 22 January the centre column (1600 Europeans, 2500 Africans), which had advanced from Rorke's Drift, was encamped near Isandlwana; on the morning of that day Lord Chelmsford split his forces and moved out to support a reconnoitring party. After he had left, the camp, in charge of Colonel Durnford, was surprised by a Zulu army nearly 20,000 strong. The British were overwhelmed and almost every man killed, the casualties being 806 Europeans (more than half belonging to the 24th regiment) and 471 Africans. Those transport buffalo not killed were seized by the Zulus. Lord Chelmsford and the reconnoitring party returned after paying little attention to the signals of attack; they arrived at the battlefield that evening and camped amidst the slaughter. The next day the survivors retreated to Rorke's Drift, which had been the scene of a successful defence. After the victory at Isandhlwana, several regiments of the Zulu army which had missed the battle had moved on to attack Rorke's Drift. The garrison stationed there, under Lieutenants John Chard and Gonville Bromhead, numbered about 80 men of the 24th regiment, and they had in the hospital there between 30 and 40 men. Late in the afternoon they were attacked by about 4000 Zulu. On six occasions, the Zulu got within the entrenchments, to be driven back each time at bayonet point. At dawn the Zulu withdrew, leaving 350 of their men dead. The British loss was 17 killed and 10 wounded.

In the meantime the Coastal column — 2700 men under Colonel Pearson — had reached Eshowe from the Tugela; on receipt of the news of Isandhlwana most of the mounted men and the native troops were sent back to the Natal, leaving at Eshowe a garrison of 1300 Europeans and 65 Africans. For two months during the Siege of Eshowe this force was hemmed in by the Zulus, and lost 20 men to sickness and disease.

The left column under Colonel (afterwards Sir) Evelyn Wood was forced onto the defensive after the disaster to the centre column. For a time the British feared an invasion of Natal.

Chelmsford had lost his centre column and his plans were in tatters. However, Zulu victory in Isandlwana had been gained with heavy casualties and Cetshwayo could not mount a counter-offensive. Chelmsford regrouped and called for reinforcements when Zulu troops kept raiding over the border. As a result of Isandlwana the British Government replaced Lord Chelmsford with Sir Garnet Wolseley but it took several weeks for him to reach Natal, during which Lord Chelmsford remained in command.

The British sent for troops from all over the empire to Cape Town. By the end of 29 March Chelmford could mount an offensive of 8500 men (including men from the Royal Navy and 91st Highlanders) from Fort Tenedos to relieve Eshowe.

During this time (12 March) an escort of stores marching to Luneberg, the headquarters of the Utrecht force, was attacked when encamped on both sides of the Intombe river. The camp was surprised, 62 out of 106 men were killed, and all the stores were lost.

The first troops arrived at Durban on 7 March. On the 29th a column, under Lord Chelmsford, consisting of 3400 European tribesmen and 2300 Africans, marched to the relief of Eshowe, entrenched camps being formed each night.

Chelmsford told Sir Evelyn Wood's troops (Staffordshire Volunteers and Boers, 675 men in total) to attack the Zulu stronghold in Hlobane. Lieutenant colonel Redvers Buller, later Second Boer War commander, led the attack on Hlobane on 28 March. However, The Zulu main army of 26,000 men arrived to help their besieged tribesmen and the British warriors scattered. Besides the loss of the African contingent (those not killed deserted) there were 100 casualties among the 400 Europeans engaged. The next day 25,000 Zulu warriors attacked Wood's camp (2068 men) in Kambula, apparently without Cetshwayo's permission. The British held them off in the Battle of Kambula and after five hours of heavy fighting the Zulus withdrew. British losses amounted to 29 the Zulus lost approximately 2000. It turned out to be a decisive battle.

On the 2nd of April the main camp was attacked at Gingingdlovu (In the Zulu language it means Swallower of the Elephant, for the British foreigners it was "Gin, Gin, I love you"), the Zulu being repulsed. Their heavy loss was estimated at 1200 while the British had only two killed and 52 wounded. The next day they relieved Pearson's men. They evacuated Eshowe on 5 April after which the Zulu forces burned it down.

Defeat of the Zulu

By the middle of April nearly all the reinforcements had reached Natal, and Lord Chelmsford reorganized his forces. The 1st division, under major-general Crealock, advanced along the coast belt and was destined to act as a support to the 2nd division, under major-general Newdigate, which with Wood's flying column, an independent unit, was to march on Ulundi from Rorke's Drift and Kambula. Owing to difficulties of transport it was the beginning of June before Newdigate was ready to advance.

The new start was not promising. Invading British troops were attacked in June 1. One of the British casualties was the exiled heir to the French throne, Napoleon Eugene Bonaparte, who had volunteered to serve in the British army and was killed while out with a reconnoitering party.

On the 1st of July Newdigate and Wood had reached the White Umfolosi, in the heart of their enemy's country. During their advance, messengers were sent by Cetshwayo to treat for peace, but he did not accept the terms offered. Meantime Sir Garnet (afterwards Lord) Wolseley had been sent out to supersede Lord Chelmsford, and on the 7th of July he reached Crealock's headquarters at Port Durnford. But by that time the campaign was practically over. The 2nd division (with which was Lord Chelmsford) and Wood's column crossed the White Umfolosi on the 4th of July the force numbering 4166 Europeans and 1005 indigenous soldiers, aided by artillery and Gatling guns. Within a mile of Ulundi the British force, formed in a hollow square, was attacked by a Zulu army numbering 12,000 to 15,000. The battle ended in a decisive victory for the British, whose losses were about 100, while of the Zulu some 1500 men lost their lives.

Aftermath

After this battle the Zulu army dispersed, most of the leading chiefs tendered their submission, and Cetshwayo became a fugitive. On the 28th August the king was captured and sent to Cape Town. (It is said that scouts spotted the water-carriers of the King, distinctive because the water was carried above, not upon, their heads). His deposition was formally announced to the Zulu, and Wolseley drew up a new scheme for the government of the country. The Chaka dynasty was deposed, and the Zulu country portioned among eleven Zulu chiefs, including Cetshwayo and one of his sons Usibepu, John Dunn, a white adventurer, and Hlubi, a Basuto chief who had done good service in the war.

Sir Frere was relegated to a minor post in Cape Town.

A Resident was appointed who was to be the channel of communication between the chiefs and the British government. This arrangement was productive of much bloodshed and disturbance, and in 1882 the British government determined to restore Cetshwayo to power. In the meantime, however, blood feuds had been engendered between the chiefs Usibepu (Zibebu) and Hamu on the one side and the tribes who supported the ex-king and his family on the other. Cetshwayo's party (who now became known as Usutus) suffered severely at the hands of the two chiefs, who were aided by a band of white freebooters.

When Cetshwayo was restored Usibepu was left in possession of his territory, while Dunn's land and that of the Basuto chief (the country between the Tugela River and the Umhlatuzi, i.e. adjoining Natal) was constituted a reserve, in which locations were to be provided for Zulu unwilling to serve the restored king. This new arrangement proved as futile as had Wolseley's. Usibepu, having created a formidable force of well-armed and trained warriors, and being left in independence on the borders of Cetshwayo's territory, viewed with displeasure the re-installation of his former king, and Cetshwayo was desirous of humbling his relative. A collision very soon took place; Usibepu's forces were victorious, and on the 22nd July 1883, led by a troop of mounted white mercenaries, he made a sudden descent upon Cetshwayo's kraal at Ulundi, which he destroyed, massacring such of the inmates of both sexes as could not save themselves by flight. The king escaped, though wounded, into Nkandla forest. After appeals by Sir Melmoth Osborn he moved to Eshowe, where he died soon after.

Anglo-Zulu war in film

Zulu_film_poster.jpg

Two film dramatizations of the war are: Zulu (1964), which is based on the Battle at Rorke's Drift, and Zulu Dawn (1979), which deals with the Battle of Isandlwana. A short and rather comical dramatization is present in Monty Python's The Meaning of Life (1983).