Shaka

|

|

- For the Shaka or Scythian dynasty of mediaeval India, see Indo-Scythians.

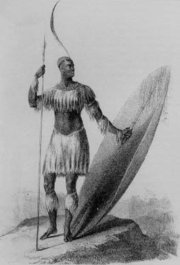

Shaka (sometimes spelled Chaka) (ca. 1781 - ca. 22nd September 1828) is widely credited with transforming the Zulu tribe from a small clan into the beginnings of a nation that held sway over that portion of Southern Africa between the Phongolo and Mzimkhulu rivers. His military prowess and destructiveness have been wildly exaggerated, as has the cohesion of the 'state' he created. Nevertheless, his statesmanship and vigour in assimilating some neighbours and ruling by proxy through others marks him as one of the greatest Zulu chieftains.

| Contents [hide] |

Sources

Scholarship over the last twenty years has radically revised our views of the sources on Shaka's reign. The earliest are two eyewitness accounts written by white adventurer-traders who met Shaka during the last four years of his reign. Nathaniel Isaacs published his Travels and Adventures in Eastern Africa in 1836, creating a picture of Shaka as a degenerate and pathological monster which survives in modified forms to this day. Isaacs was abetted in this by Henry Francis Fynn, whose so-called Diary (actually a rewritten collage of various papers)was edited up by James Stuart only in 1950. Both men were disreputable charlatans who ran guns, fought as mercenaries, murdered in cold blood, and tried to trade in slaves. This is clear from contemporary archival documents. Their now discredited accounts may be balanced by the rich resource of oral histories collected around 1900 by (ironically) the same James Stuart, now published in 6 volumes as The James Stuart Archive. This resource gives us a very different, Zulu-centred picture. Most popular accounts are based on E A Ritter's novel Shaka Zulu (1955), a potboiling romance which was re-edited by a Longmans ghostwriter into something more closely resembling a history, and thereafter swallowed whole by historians. Both its monstrous aspects and its heroic ones are largely inventions, and it must be discarded as a valid source. The work of John Wright (University of Pietermaritzburg), Julian Cobbing and Dan Wylie (Rhodes University, Grahamstown) have now definitively discredited or modified these stories.

Early years

Shaka was probably the first son of the chieftain Senzangakona and Nandi, a daughter of a past chief of the Langeni tribe, born near present-day Melmoth, KwaZulu-Natal Province. The Zulus had a practice of uku-hlobonga — a heavy-petting, safe-sex practice, that got out of hand in this case. Though conceived out of wedlock around 1781 (not 1787 as most accounts speculate, though there is little secure evidence), he was not, as the legend has it, disowned by his father or chased into exile. His parents married normally, and he was certainly not named after an intestinal beetle, though the insult became common later; he was probably named Mandhlesilo at this point. He almost certainly spent his childhood in his father's settlements, is recorded as having been initiated there and inducted into an ibutho or 'age-group regiment'. The tale of bullying by his Langeni cousin Makhadama is almost certainly a metaphor for later troubled politics between them. In fact, he did not exact revenge on the Langeni later, but largely peacefully allied with them. Most sources attest that only as a young man, when succession disputes surfaced, did Shaka conflict with his father and defect to Dingiswayo and the Mthethwa, to whom the Zulu were then paying tribute

It was probably Dingiswayo who named Shaka thus, with reference to the striking of an axe. Dingiswayo called up the emDlatsheni iNtanga (age-group), of which he was part, and incorporated it in the iziCwe regiment. He served as a Mthethwa warrior for perhaps as long as ten years, and distinguished himself with his courage, though he did not, as legend has it, rise to great position. Dingiswayo, having himself been exiled after a failed attempt to oust his father, had, along with a number of other groups in the region (including Mabhudu, Dlamini, Mkhize, Qwabe, and Ndwandwe, many probably responding to slaving pressures from southern Mozambique) helped develop new ideas of military and social organisation, in particular the ibutho, inaccurately translated as 'regiment'; it was rather an age-based labour gang which included some better-refined military activities, but by no means exclusively. Most battles before this time were to settle disputes, and while the appearance of the 'impi' (fighting unit) dramatically changed warfare at times, it largely remained a matter of seasonal raiding, political pressures rather than outright slaughter, the extent of which has been hugely exaggerated. The idea that more powerful armies caused the Mfecane migrations - conquest, disrupted societies fleeing, and in turn using the same military techniques to destroy other societies, that caused other wars and more displacement - must now be thoroughly questioned and modified; violence climbed over a period of half a century before Shaka, through multiple causes, and really exploded only after the white invasions of the late 1830s and after. The 'Mfecane' is now being discarded as a concept, and relatively few of the migrations can be directly or solely attributed to the Zulu.

Shaka's Social Revolution

On the death of Senzangakona, Dingiswayo aided Shaka to defeat his brother and assume leadership in around 1812. Shaka began further to refine the ibutho system followed by Dingiswayo and others, and with Mthethwa support over the next several years forged alliances with his smaller neighbours, mostly to counter the growing threat from Ndwandwe raiding from the north. The initial Zulu manoeuvres were strictly defensive, and mostly Shaka preferred to intervene or pressure diplomatically, aided by just a few judicial assassinations. His changes to local society built on existing structures, and were as much social and propagandistic as they were military; there were very few open fights, as the Zulu sources make clear. Shaka is often said to have been dissatisfied with the long throwing assegai, and credited with introducing a new weapon - the Iklwa, a short stabbing spear, with a long, swordlike spearhead. It was named, allegedly, for the sound made as it went in, then out, of the body. Shaka is also supposed to have introduced a larger, heavier shield made of cowhide and to have taught each warrior how to use the shield's left side to hook the enemy's shield to the right, exposing his ribs for a fatal spear stab. In fact, such tactics had been long in use, and the Zulu continued to use throwing spears, too.

Much has been made of the story that to toughen his men Shaka discarded their leather sandals, having them train and fight in bare feet. This is fiction. It's probably true, nevertheless, that Shaka's troops practiced by covering more than fifty miles in a fast trot over hot, rocky terrain in a single day so that they could surprise the enemy. Young boys from the age of six up joined Shaka's force as apprentice warriors (udibi) and served as carriers of rations and extra weapons until they joined the main ranks. This was used more for very light forces designed to extract tribute in cattle, women or young men from neighbouring groups; they preferred this surprise tactic to open battle, in which they were, contrary to popular impressions, as often unsuccessful as they were victorious. There is virtually no evidence that Shaka actually invented new tactics, or participated in battles after he became 'inkosi' or chieftain. There is only one instance in the evidence that the so-called 'horns and chest', or 'bull's head' formation was used (in 1826 against the Ndwandwe), in which event the two 'horns' accidentally ended up stabbing each other!

In the initial years, Shaka had neither the clout nor the kudos to compel any but the smallest of groups to join him, and he operated under Dingiswayo's aegis until the latter's death at the hands of Zwide's Ndwandwe. At this point Shaka was so under-resourced that he was forced to flee southwards across the Thukela river, establishing his capital Bulawayo in Qwabe territory, with Qwabe help. He never did personally move back into the traditional Zulu heartland. In Qwabe, Shaka was able to intervene in an existing succession dispute, and help his own choice, Nqetho, into power; Nqetho then ruled as a proxy chieftain for Shaka. This was the pattern, so that the bulk of the so-called Zulu kingdom at this time was ruled by almost entirely independent but friendly chieftains, including Zihlandlo of the Mkhize, Jobe of the Sithole, and Mathubane of the Thuli. These peoples were never defeated in battle by the Zulu; they did not have to be. Shaka won them over by subtler tactics of patronage and reward. The ruling Qwabe, for example, began re-inventing their genealogies to give the impression that Qwabe and Zulu were closely related in the past - a handy fiction. In this way a greater sense of cohesion was created, though it never became complete, as subsequent civil wars attest.

Hence the idea that Shaka 'changed the nature of warfare in Africa' (or even in his corner of southern Africa) from 'a ritualised exchange of taunts with minimal loss of life into a true method of subjugation by wholesale slaughter', is a wild exaggeration. There is virtually no evidence in the Zulu sources that any such slaughter occurred - with the solitary exception of a renegade unit, the iziYendane, who went on a horrific but geographically limited rampage south of the Thukela, against Shaka's orders; when he learned the truth, he killed off the leaders and disbanded the unit. Some of them consequently conspired with his half-brother Dingane to assassinate Shaka.

The major conflicts

In 1816, after the death of his father, Shaka had seized power over the then-insignificant Zulu clan. Though he was boosted in by the Mthethwa, and his brother Sigujana was killed, the coup was relatively bloodless and accepted by the Zulu. Shaka still recognised Dingiswayo and his larger Mthethwa clan as overlord after he returned to the Zulu, but some years later Dingiswayo was ambushed by Ndwandwe and killed. There is absolutely no evidence to suggest that Shaka betrayed Dingiswayo. Indeed, the core Zulu had to retreat before several Ndwandwe incursions; the Ndwandwe were clearly the most aggressive grouping in the sub-region.

Shaka was able to form an alliance with the leaderless Mthethwa clan, and was able to establish himself amongst the Qwabe, after Phakathwayo was overthrown without much of a fight, if any. With Qwabe, Hlubi and Mkhize support, Shaka was finally able to summons a force capable of resisting the Ndwandwe. It is asserted everywhere that his first major battle against Zwide of the Ndwandwe was the Battle of Gqokli Hill, on the Mfolozi river. In fact this battle is a pure invention of E A Ritter's: there is not a single scrap of evidence in preceding literature and records that it ever happened. One minor scrap is attested to, known as the 'kisi' fight, in which a night fight occurred; Shaka is said to have told his troops to use the password 'kisi' to avoid stabbing each other; the outcome is unclear in the sources. This is the sole example of a tactic being suggested by Shaka.

The decisive fight eventually took place on the Mhlatuze river, at the confluence with the Mvuzane stream. This is very well attested in Zulu accounts, with only minor variations in detail. Shaka feinted a retreat,then caught the lightly-equipped Ndwandwe on the river bank and inflicted a resounding defeat. The Zulu force pursued the invaders to Zwide's capital, but failed to capture the chief. In fact, the Ndwandwe remained formidable; Zwide did move off north, to inflict further damage on less resistant foes and avail himself of slaving opportunities, and Shaka later had to contend again with Zwide's son, Sikhunyane, in 1826.

Mfecane - The Scattering

- See main article: Mfecane

The increased military efficiency led to more and more clans being incorporated into Shaka's Zulu empire, while other tribes moved away to be out of range of Shaka's impis. The ripple effect caused by these mass migrations would become known (though only in the twentieth century) as the Mfecane. Some groups which moved off were (like the Hlubi and Ngwane to the north of the Zulus) impelled by the Ndwandwe, not the Zulu. Some moved south (like the Chunu and the Thembe), but never suffered much in the way of attack; it was precautionary, and they left many people behind in their traditional homelands. It is often asserted that Mzilikaziof the Khumalo was a 'general' of Shaka's, who fled; but there is no evidence for this, or that there was a major fight. Mzilikazi moved away with a small group, and his path into Zimbabwe over twenty years was impelled by forces which had nothing to do with Shaka at all. The Jere and Msana groups under Shoshangane and Zwangendaba, who were allied to Zwide and moved north after the Mhlatuze fight, were never attacked by Shaka, and probably moved more to take advantage of slaving opportunities in Mozambique than out of fear of the Zulu. Hence the term 'Mfecane' is falling into disfavour with scholars.

This is not to say that the Zulu did not themselves show aggression or competence. Shaka was clearly a tough, able leader, the most able of his time, and during the last four years of his reign indulged in several long-distance raids. Two were against the Mpondo to the south, an increasing vector of his attention (Shaka moved his capital southwards even further in 1827, to Dukuza); the first, in 1824, was a failure; the second in 1828, only partly successful. A raid against Macingwane of the Chunu, possibly in 1825, is virtually the only one which conforms to the stereotype of the large Zulu army inflicting a serious defeat on another large force. A totally unauthorised raid, led by Dingane against Matiwane of the Ngwane in 1826, was a disaster; and so was an ill-explained foray towards Delagoa Bay in 1828, the so-called 'Balule' campaign. Only in 1826, against Sikhunyane, was there an unqualified victory which allowed Zulu sovereignty to be extended (though again under a proxy ruler, Maphitha). In no case does there appear to have been widespread slaughter, and the record is at best mixed. The 'nation' was cobbled together under difficult circumstances and with patchy success - and there was always internal dissention to deal with.

Death and Succession

When the walls fell, Dingane and Mhlangana, Shaka's half-brothers, appear to have made at least two attempts to assassinate Shaka before they succeeded, with support from Mpondo elements, some disaffected iziYendane people, and the white traders at Port Natal (now Durban). The details must remain controversial, including the exact date (late September 1828). What is clear is that Dingane was obliged to embark on an extensive purge of pro-Shaka elements and chieftains, running over several years, in order to secure his position. A virtual civil war broke out. Dingane ruled for some twelve years, during which time he was obliged to fight, disastrously, against the Voortrekkers, and against another half-brother Mpande, who with Boer and British support, took over the Zulu leadership in 1840, and ruled for some 30 years. Later in the 19th century the Zulus would be one of the few African peoples who managed to defeat the British Army at the Battle of Isandlwana.

See also

- List of Zulu kings

- King Dingiswayo of the Mthethwa

- King Moshoeshoe I of Lesotho

- King Zwide of the Ndwandwe

- King Mzilikazi of the Ndebele

- Father Senzangakona, mother Nandi

- Brother, assassinator, successor Dingane

- Brother, assassinator, Umthlangana

- Brother, later successor Mpande

- Shaka Zulu, an SABC TV series about Shaka

- List of South Africans - Voted 14th in the TV Show 100 Greatest South Africans

External links

- The South African Military History Society - The Zulu Military Organization and the Challenge of 1879 (http://www.rapidttp.com/milhist/vol044sb.html)de:Shaka