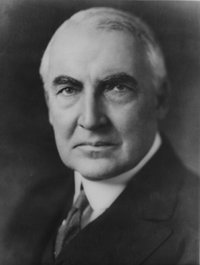

Warren G. Harding

|

|

| ||

| Order: | 29th President | |

| Vice President: | Calvin Coolidge | |

| Term of office: | March 4, 1921 – August 2, 1923 | |

| Preceded by: | Woodrow Wilson | |

| Succeeded by: | Calvin Coolidge | |

| Date of birth: | November 2, 1865 | |

| Place of birth: | Near Blooming Grove, Ohio | |

| Date of death: | August 2, 1923 | |

| Place of death: | San Francisco, California | |

| First Lady: | Florence Kling Harding | |

| Political party: | Republican party | |

Warren Gamaliel Harding (November 2, 1865–August 2, 1923) was an American politician and the 29th President of the United States, serving from 1921 to 1923, when he became the sixth president to die in office. A Republican from the U.S. state of Ohio, Harding was an influential newspaper publisher with a flair for public speaking before entering politics, first in the Ohio Senate (1899–1903) and later as Lieutenant Governor (1903–1905).

Harding was elected to the Ohio State Senate in 1899. He served four years before being elected Lieutenant Governor of Ohio, a post he occupied from 1903 to 1905. His leanings were conservative, his record in both offices relatively undistinguished. At the conclusion of his term, Harding returned to private life, only to reenter politics ten years later as a U.S. Senator (1914–1921), where he again had a relatively undistinguished record, missing over two-thirds of the roll-call votes. A political unknown at the time of the 1920 Republican National Convention, Harding emerged as a dark horse to become the presidential nominee through political maneuvering. In the 1920 election he defeated his Democratic opponent James M. Cox in a landslide, 60.36 to 34.19 percent (404 to 127 in the electoral college). He adopted hands-off laissez-faire policies both on economic and social policy. Plagued by scandals in his administration—despite being personally honest—Harding died suddenly three years into his term due to complications from pneumonia and possible food poisoning. He was succeeded by Vice President Calvin Coolidge.

| Contents |

Early life

Harding was born on November 2, 1865, near Corsica, Ohio (now Blooming Grove) in Morrow County. Harding was the oldest of the eight children of Dr. George Harding and Phoebe Dickerson Harding. His boyhood heroes were Alexander Hamilton and Napoleon. His mother was a midwife who later obtained her medical license. While a teenager, the Harding family moved to Caledonia in neighboring Marion County when Harding's father acquired The Argus, a local weekly newspaper, where Harding learned the basics of the newspaper business. Harding's education was completed at Ohio Central College (later Muskingum College) in Iberia.

After graduation, Harding moved to Marion, where he raised $300 with two friends to purchase the failing Marion Daily Star. It was the weakest of Marion's three newspapers and the only daily in the growing city. Harding converted the paper's editorial platform to support the Republicans and enjoyed a moderate degree of success. However, Harding's political stance was at odds with those who controlled most of Marion's local politics. When Harding moved to unseat the Marion Independent as the official paper of daily record, his actions brought the wrath of Amos Kling, one of Marion's wealthiest real estate speculators, down upon him.

While Harding won the war of words and made the Daily Star the biggest newspaper in Marion, the battle took a toll on his health. In 1889, when Harding was 24, he suffered exhaustion and nervous fatigue. He traveled to Battle Creek, Michigan to spend several weeks in a sanitarium regaining his strength, later returning to Marion to continue operating the Star. He spent his days boosting the community on the editorial pages, and his evenings "bloviating" (Harding's term for informal conversation) with his friends over games of poker.

In 1891, Harding married Florence Mabel Kling DeWolfe, a divorcee and the mother of one son. Five years older than Harding, she had pursued him persistently, until he reluctantly surrendered and proposed. Florence's father was Harding's nemesis, Amos Kling. Upon hearing that his only daughter intended to marry Harding, Amos Kling cut her completely out of the family and even forbade his wife to attend her wedding. He opposed the marriage vigorously and would not speak to his daughter or son-in-law for eight years.

While the marriage was not one of full-blown passions, the couple complemented one another, Harding's affable personality balancing his wife's no-nonsense approach to life. Florence Harding inherited her father's determination and business sense, and turned the Marion Daily Star into a profitable business. One of the Hardings' paperboys at the Star was the young Norman Thomas, son of the city's Presbyterian Church minister, who later became a noted journalist and socialist leader in New York City. Thomas, who ran for President on the socialist ticket, often credited his work ethic to Florence Harding, whom he remembered fondly in his recollections of life in Marion. Florence's drive has been credited with helping Harding to achieve greater things than he could have done alone, leading to speculation that she later pushed him all the way to the White House.

Harding was also a member of the Freemasons. He was raised to the Sublime Degree of a Master Mason on August 27, 1920, in Marion Lodge No. 70, F. & A.M., Marion, Ohio.

Political rise

As an influential newspaper publisher with a flair for public speaking, Harding was elected to the Ohio State Senate in 1899. He served four years before being elected Lieutenant Governor of Ohio, a post he occupied from 1903 to 1905. His leanings were conservative, his record in both offices relatively undistinguished. At the conclusion of his term as Lieutenant Governor Harding returned to private life.

Senator

Re-entering politics five years later later, Harding lost a race for governor in 1910, but won election to the United States Senate in 1914, serving from 1915 until his inauguration on Friday, March 4, 1921, having earned the distinction of becoming the first sitting Senator to be elected President.

As with his first term as Senator, Harding had a relatively undistinguished record, missing over two-thirds of the roll-call votes. Among them was the vote to send the 19th Amendment (granting Women's Suffrage) to the states for ratification, a measure he had supported.

Election of 1920

Main article: U.S. presidential election, 1920

A relative unknown outside his own state, Harding was a true "dark horse" candidate, winning the Republican Party nomination due to the political machinations of his friends after the nominating convention had become deadlocked. Before receiving the nomination, he was asked whether there were any embarrassing episodes in his past that might be used against him. His formal education was limited, he had a longstanding affair with the wife of an old friend, and was a social drinker. Harding answered "No" and the Party moved to nominate him, only to discover later his relationship with Carrie Fulton Phillips. Phillips and her family received an extended tour of Asia courtesy of the Republican Party in exchange for her silence. Mrs. Harding's newlywed brother Vetallis ("Tal") Kling and his bride Elnora ("Nona") Younkins-Hinaman also received a full expenses-paid tour of Europe from the Hardings; the bride was a Catholic widow, and the marriage performed in the Catholic Church at a time when Catholics were viewed as a liability in American politics and the recently revived Ku Klux Klan, anti-Catholic as well as anti-black and anti-Jewish, was rapidly becoming popular in the Midwest.

In the 1920 election, Harding ran against Democrat Ohio Governor James M. Cox, whose vice presidential candidate was Assistant Secretary of the Navy Franklin D. Roosevelt. The election was seen in part as a referendum on whether to continue with the progressive work of the Woodrow Wilson administration or to revert to the laissez-faire approach of the William McKinley era.

Harding ran on a promise to "Return to Normalcy," a term he coined, which reflected three trends of his time: a renewed isolationism in reaction to World War I, a resurgence of nativism, and a turning away from the government activism of the reform era.

Harding's "Front Porch Campaign" during the late summer and fall of 1920 captured the imagination of the country. Not only was it the first campaign to be heavily covered by the press, and to receive widespread newsreel coverage, but it was also the first modern campaign to use the power of Hollywood and Broadway stars who traveled to Marion for photo opportunities with Harding and his wife. Al Jolson, Lillian Russell, Douglas Fairbanks and Mary Pickford were among the luminaries to make the pilgrimage to central Ohio. Business icons Thomas Edison, Henry Ford and Harvey Firestone also lent their cachet to the Front Porch Campaign. From the onset of the campaign until the November election, over 600,000 people traveled to Marion to participate.

The campaign owed a great deal to Florence Harding, who played perhaps a more active role than any previous candidate's wife in a Presidential race. She cultivated the relationship between the campaign and the press; as the business manager of the Star, she understood reporters and their industry and played to their needs by making herself freely available to answer questions, pose for pictures or deliver home cooked food from her kitchen to the press office, a bungalow she had constructed at the rear of their property in Marion. Mrs. Harding even went so far as to coach her husband on the proper way to wave to newsreel cameras to make the most of coverage.

The campaign also drew upon Harding's popularity with women. Considered handsome, Harding photographed well compared to Cox. However, it was Harding's support for women's suffrage in the Senate that made him extremely popular with women: the ratification of the 19th Amendment to the Constitution in August 1920 brought huge crowds of women to Marion, Ohio to hear Harding.

During the campaign, rumors were spread by persons (unaffiliated with the Cox campaign) that Harding's great-great-grandfather was a West Indian black and that other blacks lurked in his family tree (see Scandals, below). In response, Harding's campaign manager said "No family in the state [of Ohio] has a clearer, a more honorable record than the Hardings, a blue-eyed stock from New England and Pennsylvania, the finest pioneer blood." To a friend, however, Harding confided that one of his ancestors may have "jumped the fence," though Harding himself was never certain whether or not this was true. These rumors, perhaps based on no more than local Ohio gossip, were circulated by William Estabrook Chancellor.

The milestone election of 1920 was the first in which women could vote nationwide. Harding received 61 percent of the national vote and 404 electoral votes, an unprecedented margin of victory. Cox received 36 percent of the national vote and 127 electoral votes. Socialist Eugene V. Debs, campaigning from Federal prison, received 3 percent of the national vote.

Presidency

Throughout his administration, Harding adopted laissez-faire policies, and there are few lasting achievements to his name. One important event, however, was the Washington Naval Conference of 1921-1922, which at Secretary of State Charles Evans Hughes' instigation limited the size of navies and reduced tension between the US, the UK and Japan in the Pacific. Also notable was the establishment of the Bureau of the Budget (now the Office of Management and Budget), which increased the powers of the President by directing departmental spending plans to him rather than to U.S. Congress, and the General Accounting Office to audit government expenditiures. Harding was also able to bring the reality of an eight-hour work day to millions of Americans (which happened some days after his death). In a special session of congress shortly after his inaugaration he called for retrenchment of government, low taxes, repeal of the wartimes excesses tax, reduction of railroad rates, a great merchant marine, a Public Welfare Department (realized in 1953 as U.S Health, Education and Welfare Department), a national budget system and promotion of agricultural interests.

In 1921, Harding delivered a speech while on a trip to the state of Alabama, making him the first United States President to advocate the rights of blacks while on southern soil.

As President, Harding played both golf (in season) and poker twice a week. Although as a U.S. senator from Ohio he had voted for Prohibition, Harding kept the White House well stocked with bootleg liquor. He attended baseball games regularly.

Despite the reputation that later clung to him, Harding did appoint several capable and honest men to his Cabinet, including especially Hughes, Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover, Secretary of the Treasury Andrew Mellon, Secretary of War John W. Weeks, Postmaster General Will Hays, and Secretary of Agriculture Henry C. Wallace. Wallace was the father of Henry A. Wallace, the future Cabinet Secretary, Vice President and 1948 progressive presidential candidate.

Both President Harding and his wife were extremely popular during their tenure in the White House.

Cabinet

Supreme Court appointments

Harding appointed the following justices to the Supreme Court of the United States:

- William Howard Taft - Chief Justice - 1921

- Harding was the only President to have appointed a previous President as chief justice (or associate justice, for that matter; Taft is the only person to have served as both President and Supreme Court Justice).

- George Sutherland - 1922

- Pierce Butler - 1923

- Edward Terry Sanford - 1923

Death

In June of 1923, Harding set out on a cross-country "Voyage of Understanding," planning to meet ordinary people and explain his policies. During this trip, he became the first President to visit Alaska. Rumors of corruption in his administration were beginning to circulate in Washington by this time, and Harding was profoundly shocked by a long message he received while in Alaska, apparently detailing illegal activities previously unknown to him. At the end of July, while traveling south from Alaska, he developed what was thought to be a severe case of food poisoning. Arriving at the Palace Hotel in San Francisco, he developed pneumonia. Harding died of either a heart attack or a stroke at 7:35 p.m. on August 2, 1923 at age 57. Naval physicians surmised that he had suffered a heart attack; however, this diagnosis was not made by Dr. Charles Sawyer, the Surgeon General, who was traveling with the presidential party. Upon Sawyer's recommendation, Mrs. Harding refused permission for an autopsy, which soon led to speculation that the President had been the victim of a plot. Sawyer's medical qualifications were also called into question. Harding was succeeded by his Vice President, Calvin Coolidge, who was sworn in by his father, a Justice of the Peace, in Plymouth Notch, Vermont.

Following his death, Harding's body was returned to Washington, where it was placed in the Gold Room of the White House pending a state funeral at the United States Capitol. White House employees at the time were quoted as saying that the night before the funeral, they heard Mrs. Harding speak for more than an hour to the face of her dead husband. The most commonly reported (though never verified) remark attributed to Mrs. Harding at this time was: "They can't hurt you now, Warren."

Harding was entombed in the receiving vault of the Marion Cemetery, Marion, Ohio, in August 1923. Following Mrs. Harding's death in November 1924, she too was temporarily buried next to her husband. Both bodies were moved in December 1927 to the newly completed Harding Memorial in Marion, which was dedicated by President Herbert Hoover in 1931. The lapse between the final interment and the dedication was due in part to the aftermath of the Teapot Dome scandal.

In 1930, a former private investigator named Gaston Means wrote the exploitative book, The Strange Death of President Harding, in which he suggested many people had motives to murder the President, including his wife. Means claimed it was possible that Mrs. Harding poisoned the President, a rumor that has clouded the facts of Harding's death and heart condition. In 1933, an expos頩n Liberty magazine denounced Means as a fraud who used a ghost writer for The Strange Death of President Harding. The theories advanced by Means—who had previously been imprisoned for his suspect activities while an FBI agent—have never been proven; they remain as speculative as they were sensational.

Scandals

Harding's detractors began using the damaging rumor of his alleged negro ancestry against him in the 1880s, early in his political career. Among those spreading the rumor was Amos Kling, one of Marion's wealthiest citizens, who detested Harding and his newspaper, The Marion Daily Star. Kling got his comeuppance when his daughter Florence Kling DeWolfe married Harding. Eventually the Hardings and Klings reconciled, but the rumors persisted.

Those who hold to the theory of mixed race do so without proof, often relying on the research of William Estabrook Chancellor for details of Harding's supposed African-American lineage. There is no scientific or legal basis for these arguments. Chancellor's work never provided clear indications of his resources, or his proof. In fact, so few copies of his book exist—one of five known copies is owned by a private book collector in Marion, Ohio—that its availability to modern scholars is limited at best. Furthermore, there has never been a test of Harding's DNA. The claim is also impossible to verify through public records in Ohio; Harding was born in 1865, and the state of Ohio did not require registration or recording of births until 1867. Furthermore, Chancellor's theories find no basis in Federal Census Records, nor in probate court records. Harding's 1923 California-issued death certificate also indicates nothing to suggest Chancellor's theories were accepted as fact. With the release in the 1960s of Francis Russell's The Shadow of Blooming Grove, the specter of Harding's mixed blood was again raised and, lacking factual sources, quickly put down as innuendo.

Upon winning the election, Harding placed many of his old allies and cronies in prominent political positions. Known as the "Ohio Gang" (a misleading term used by Charles Mee, Jr., for his book of the same name), some of the appointees used their new powers to rob the government. Corruption was rampant throughout Harding's administration, though it is uncertain how much Harding himself knew about his friends' illicit activities. The most infamous scandal of the time was the Teapot Dome affair, which shook the nation for years after Harding's death. The scandal involved Secretary of the Interior Albert B. Fall, who was eventually convicted of covertly leasing public oil fields to business associates in exchange for personal loans. In 1931 Fall became the first member of a Cabinet to be sent to prison.

Thomas Miller, head of the Office of Alien Property, was convicted of accepting bribes. Jess Smith, personal aide to the Attorney General, destroyed papers and then committed suicide. Charles Forbes, Director of the Veterans Bureau, skimmed profits, earned fat kickbacks, and ran alcohol and drugs. He was convicted of fraud and bribery and drew a two-year sentence. Charles Cramer, an aide to Charles Forbes, also committed suicide.

No evidence to date suggests that Harding personally profited from these crimes, but he was apparently unable to stop them. "My God, this is a hell of a job!" Harding said. "I have no trouble with my enemies, but my damn friends, they're the ones that keep me walking the floor nights."

Extramarital affairs

Many self-appointed experts on Harding's infidelities base their suppositions on innuendo, speculation, and stories that swirled around the President following his death. What is known, and has been recorded in primary documents, is that during his lifetime, Harding had an affair with Mrs. Carrie Fulton Phillips; he was also rumored to have had an affair with Miss Nan Britton, though information for this comes mostly from her book, written after his death.

Rumors of the Harding love letters circulated through Marion, Ohio for many years. However, their existence was not confirmed until author Francis Russell gained access to them during his research for his book, The Shadow of Blooming Grove. The letters were in the possession of Harding's one true love, Carrie Fulton Phillips, who by the 1960s was very elderly. Phillips kept the letters in a box in a closet and was reluctant to share them. Russell persuaded her to relent, and the letters showed conclusively that Harding had a 15-year relationship with Mrs. Phillips, who was then the wife of his friend James Phillips, owner of the local department store, the Uhler-Phillips Company. Mrs. Phillips was ten years younger than Harding. By 1915, she began pressing Harding to leave his wife. When he refused, she left her husband and moved to Berlin with her daughter Isabel. However, as the United States became increasingly likely to be drawn into World War I, Mrs. Phillips moved back to the U.S. and the affair reignited. Harding was now an Ohio Senator, and a vote was coming up on a declaration of war against Germany.

Mrs. Phillips threatened to go public with their affair if the Senator supported the war, but Harding defied her and voted for war, and Carrie did not reveal the scandal to the world. When Harding won the Republican presidential nomination in 1920, he did not disclose the relationship to party officials. Once they learned of the affair, it was too late to find another nominee. To reduce the likelihood of a scandal breaking, the Republican National Committee sent Carrie and her family on a trip to Japan and paid them over $50,000. Mrs. Phillips also received monthly payments thereafter, becoming the first and only person known to have successfully extorted money from a major political party.

The letters Harding wrote to Mrs. Phillips were confiscated at the request of the Harding heirs, who requested and received a court injunction prohibiting their inclusion in Francis Russell's book, The Shadow of Blooming Grove. Russell in turn left quoted passages from the letters as blank passages in protest against the Harding heirs' actions. The Harding-Phillips love letters remain under an Ohio court protective order that expires in 2024, after which the content of the letters may be published and/or reviewed.

Besides Mrs. Phillips, Harding also reportedly had an affair with Nan Britton, the daughter of Harding's late friend, a Dr. Britton of Marion. Nan's obsession with Harding started at an early age when she began pasting pictures of then-Senator Harding on her bedroom walls. According to Nan's kiss-and-tell book The President's Daughter, published after Harding's death, she and Senator Harding conceived "their" daughter, Elizabeth Ann, in January 1919 in his Senate office. Harding never met Nan's daughter, but paid large amounts of child support. Harding and Britton, according to unsubstantiated reports, continued their affair while he was President, using a closet adjacent to the Oval Office for privacy. Following Harding's death, Nan Britton unsuccessfully sued the estate of Warren G. Harding on behalf of Elizabeth Ann. Under cross-examination by the Harding heirs' attorney, Grant Mouser (a former member of Congress himself), Britton's testimony was riddled with inconsistencies, and she lost her case. Britton married a Mr. Christian, who adopted Elizabeth Ann. Now Elizabeth Ann Blaesing, Nan Britton's daughter has been a resident of California for most of her life and was still living as of 2002.

History Clipart and Pictures

- Pictures of the US Presidents (http://classroomclipart.com/cgi-bin/kids/imageFolio.cgi?direct=History/United_States/Presidents)

- Clipart of American Presidents (http://classroomclipart.com/cgi-bin/kids/imageFolio.cgi?direct=Clipart/American_Presidents)

- Historical Pictures of the United States (http://classroomclipart.com/cgi-bin/kids/imageFolio.cgi?direct=History/United_States)

- Pictures of the American Revolution (http://classroomclipart.com/cgi-bin/kids/imageFolio.cgi?direct=History/United_States/American_Revolution)

- Civil Rights Pictures (http://classroomclipart.com/cgi-bin/kids/imageFolio.cgi?direct=History/United_States/Civil_Rights)

- Civil War Images (http://classroomclipart.com/cgi-bin/kids/imageFolio.cgi?direct=History/United_States/Civil_War)

- Pictures of Colonial America (http://classroomclipart.com/cgi-bin/kids/imageFolio.cgi?direct=History/United_States/Colonial_America)

- Historical US Illustrations (http://classroomclipart.com/cgi-bin/kids/imageFolio.cgi?direct=History/United_States/Illustrations)

- World War II Pictures (http://classroomclipart.com/cgi-bin/kids/imageFolio.cgi?direct=History/United_States/World_War_II)

- Pictures of Historical People (http://classroomclipart.com/cgi-bin/kids/imageFolio.cgi?direct=History/United_States/People)

External links

- Audio clips of Harding's speeches (http://vvl.lib.msu.edu/showfindingaid.cfm?findaidid=HardingW)

- Inaugural Address (http://www.usa-presidents.info/inaugural/harding.html)

- The Harding home (historic site, Ohio) (http://www.ohiohistory.org/places/harding/)

- First State of the Union Address of Warren Harding (http://www.usa-presidents.info/union/harding-1.html)

- Second State of the Union Address of Warren Harding (http://www.usa-presidents.info/union/harding-2.html)

- C-Span The American Presidents (http://www.americanpresidents.org/presidents/president.asp?PresidentNumber=28)

- Warren G. Harding Links (http://www.davidpietrusza.com/Harding-links.html)