United States Declaration of Independence

|

|

Us-decl-indep.jpg

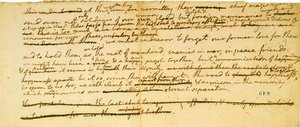

The Declaration of Independence is the document in which the Thirteen Colonies declared themselves independent of the Kingdom of Great Britain and explained their justifications for doing so. It was ratified by the Continental Congress on July 4, 1776; this anniversary is celebrated as Independence Day in the United States. The document is on display in the National Archives in Washington, D.C. The independence of the American colonies was recognized by Great Britain on September 3, 1783, by the Treaty of Paris.

| Contents |

Background

Throughout the 1760s and 1770s, relations between Great Britain and thirteen of her North American colonies had become increasingly strained. Fighting broke out in 1775 at Lexington and Concord marking the beginning of the American Revolutionary War. Although there was little initial sentiment for outright independence, the pamphlet Common Sense by Thomas Paine was able to promote the belief that total independence was the only possible route for the colonies.

Independence was adopted on July 2, 1776 pursuant to the "Lee Resolution" presented to the Continental Congress by Richard Henry Lee of Virginia on June 7, 1776, which read (in part): "Resolved: That these United Colonies are, and of right ought to be, free and independent States, that they are absolved from all allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the State of Great Britain is, and ought to be, totally dissolved."

On June 11, 1776, a committee consisting of John Adams of Massachusetts, Benjamin Franklin of Pennsylvania, Thomas Jefferson of Virginia, Robert R. Livingston of New York, and Roger Sherman of Connecticut, was formed to draft a suitable declaration to frame this resolution. Jefferson did most of the writing, with input from the committee. His original draft included a denunciation of the slave trade, which was later edited out, as was a lengthy criticism of the British people and parliament. His draft was presented to the Continental Congress on July 1, 1776. The Declaration was rewritten somewhat in general session prior to its adoption by the Continental Congress on July 4, 1776, at the Pennsylvania State House. While a critic of British policy, John Dickinson did not agree to this declaration. The adopted copy was then sent a few blocks away to the printing shop of John Dunlap. Through the night between 150 and 200 copies were made, now known as "Dunlap broadsides". The 25 Dunlap broadsides still known to exist are the oldest surviving copies of the document.

The declaration

The Declaration is divided into three main sections: a preamble, a list of grievances, and a conclusion:

1. Authority for Declaration stated to be Laws of Nature and Nature's God.

2. Self-evident truths: all men are created equal.

3. Nature's God, Creator of the Laws of Nature has endowed men with certain unalienable rights.

4. Among these unalienable rights are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.

5. Governments are established to safeguard these rights, and derive their just power from the consent of the governed

6. Whenever a government neglects its duties, the people have a right to change or abolish it and form a new government that will guarantee their safety and happiness

7. Long-established governments should not be overthrown for trivial reasons

8. However, repeated crimes and abuses require that the people revolt

9. Such has been the case with Great Britain

The Declaration then backs up its argument with a long list of grievances against the King and his actions. There are some historians that claim that many of the complaints are exaggerated propaganda, but that overall they are an accurate portrayal of royal crimes. Once the King's guilt is sufficiently proven, the document concludes with a statement on British-American relationships, a formal declaration of America's independence and powers as a sovereign nation, and a pledge by the signers to support the Declaration with their "Lives," "Fortunes," and "sacred Honor."

On July 19, 1776, Congress ordered a copy be handwritten for the delegates to sign. This copy of the Declaration was produced by Timothy Matlack, assistant to the secretary of Congress. Most of the delegates signed it on August 2, 1776, in geographic order of their colonies from north to south, though some delegates were not present and had to sign later. Two delegates never signed at all. As new delegates joined the congress, they were also allowed to sign. A total of 56 delegates eventually signed. This is the copy on display at the National Archives. Word of the declaration reached London on August 10.

Several myths surround the document: because it is dated July 4, 1776, many people falsely believe it was signed on that date. John Hancock's name is larger than that of the other signatories, and an unfounded legend states that it is large so that King George III would be able to read it without his spectacles. A painting by John Trumbull, depicting the signing of the Declaration with all representatives present, hangs in the grand Rotunda of the Capitol of the United States: no such ceremony ever took place. There is no evidence that Benjamin Franklin ever made the statement often attributed to him: "We must all hang together, or most assuredly we shall hang separately". The Liberty Bell was not rung to celebrate independence, and it certainly did not acquire its crack on so doing: that story comes from a children's book of fiction, Legends of the American Revolution, by George Lippard. The Liberty Bell was actually named in the early nineteenth century when it became a symbol of the anti-slavery movement.

Syng_inkstand.jpg

A fictionalized (but somewhat historically accurate) version of how the Declaration came about is the musical play (and 1972 movie) 1776, which is usually termed a "musical comedy" but deals frankly with the political issues, especially how disagreement over the institution of slavery almost defeated the Declaration's adoption.

Some historians believe that the Declaration was used as a propaganda tool, in which the Americans tried to establish clear reasons for their rebellion that might persuade reluctant colonists to join them and establish their just cause to foreign governments that might lend them aid. The Declaration also served to unite the members of the Continental Congress. Most were aware that they were signing what would be their death warrant in case the Revolution failed, and the Declaration served to make anything short of victory in the Revolution unthinkable.

The Declaration appeals strongly to the concept of natural law and self-determination. The Declaration is heavily influenced by the Oath of Abjuration of the Dutch Republic and by the Discourses of Algernon Sydney, to whose legacy Jefferson and Adams were equally devoted. Ideas and even some of the phrasing was taken directly from the writings of John Locke, particularly his second treatise on government, titled "Essay Concerning the true original, extent, and end of Civil Government."

The Declaration of Independence contains many of the founding fathers' fundamental principles, some of which were later codified in the United States Constitution. It has also been used as the model of a number of later documents such as the declarations of independence of Vietnam and Rhodesia.

Philosophical background

The major difference between the application of the two words unalienable and inalienable, aside from the spelling, seems to be an original belief in a point of origin of these rights. In the original context of unalienable attribution is given to Nature's God and not to another human being. Inalienable, on the other hand, conotates a secular imperative, not contingent on an Origin.

According to Black's Law Dictionary, inalienable rights are rights which are not capable of being surrendered or transferred without the consent of the one possessing such rights, which include the rights of free speech, property ownership, freedom of religion, and personal liberty. Barron's Law Dictionary states that they are fundamental rights, including the right to practice religion, freedom of speech, due process, and equal protection under the laws, that cannot be transferred to another nor surrendered except by the person possessing them.

The 17th Century point of origination of the unalienable rights appears to have flowed through the pen of Thomas Paine who constantly used the word unalienable and who, in his other writings (such as The Age of Reason), lashed out at organized religion while maintaining attribution to a Creator. Others took this approach one step further into the philosophy of humanism which in turn gave birth to the concept of human rights. While some similarity can also be found in the works of the English political philosopher John Locke and especially his The Second Treatise of Government, Jefferson departed from Locke over his idea that property ownership could have flowed from Nature's God, but considered human rights, rather, a secular imperative, hence "inalienable", as distinct from "unalienable". As a secular imperative, these rights cannot be transferred nor surrendered by another, whether "God" or human, because they are "intrinsic and inherent" (as he wrote in the original draft of the Declaration) as distinct from "flowing from", i.e. originally possessed by the individual, not given to the individual by another, "original" possessor, such as Nature's God, and thereby not disputable under any circumstance, religious or otherwise.

Thomas Paine who was a Quaker, enjoyed similar views to fellow Englishman Freeborn John Lilburne of the generation before. He shared similar ideas and he had also become a member of the Quaker faith. Paine, like Lilburne, while contributing much to the foundation of the organic law upon which the United States was built, was in his day brushed aside and for many years forgotten while others took the credit for his work.

As a result of the writings of United States Supreme Court Justice Hugo Black, beginning with Adamson v. California in 1947 and many other case opinions that climaxed in Miranda v. Arizona in 1966 which incorporated references to John Lilburne and his court cases; followed by his major article for the 1968 Yearbook of Encyclop�dia Britannica, the work of John Lilburne (especially his contribution to the third constitutional draft of An Agreement of the Free People of England in 1649, have now been accepted by scholars on both the right and left as being the bedrock source for the United States Bill of Rights.

Inalienable vs. unalienable

Many questions have been raised concerning the use of the word unalienable rather than inalienable. The Constitution of Pennsylvania, dated August 16, 1776 also uses the word unalienable, rather than inalienable. Suggestions as to the origins of the use of this word in the context of both the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution of Pennsylvania, have pointed to a common source of inspiration in the writings and ideas of Thomas Paine which predate the Declaration of Independence.

While Thomas Jefferson is popularly accredited with being the author of the Declaration, it is clear from the record that he was not its originator. Both John Adams and Jefferson began with copies of a similar document that was written in the writing style of Thomas Paine who also used the word unalienable. Paine was also a major advocate for the abolition of slavery. Jefferson's original draft of the Declaration included a paragraph attacking both slavery and the Christian king who championed it. Jefferson's first documented use of the phrase "all men are born free" was as a lawyer in defense of a man of mixed race seeking his freedom (Jefferson lost that case). For the next 50 years, until his death on July 4, 1826, Jefferson was frequently asked for a copy of the Declaration. He would always send the original draft, with the condemnation of the slave trade, and the other deletions voted by the Continental Congress noted. He never believed that the final document was "better" than the original.

It was Jefferson and not Paine who was given full credit for the Declaration, while Paine who had advocated the ideas behind the Revolution itself, died a poor, broken and despised man. Generations had to pass before historians began to understand the true importance of Thomas Paine.

The fact that Thomas Jefferson took full credit for something that was not necessarily his to take credit for, is reflected in behavior of Thomas Jefferson with regards to all matters that he did not wish to address. He avoided them, brushed over them or portrayed them in a slightly different manner. Thus Jefferson avoided all discussion about his familial relationship to John Lilburne, by suggesting that little was known about his family history when the reverse was true. Thomas Paine quickly lost favor with the up and coming ruling class of the Revolution, primarily because of his stand against slavery.

The final working draft of the Declaration, authored by Thomas Jefferson, used the spelling inalienable. The original signed version of the final draft (the master document) of the Declaration of Independence and the inscription on the Jefferson Memorial both read inalienable. (Inalienable etymologically, comes from the French word inali�nable.) When subsequent printed and hand-copied reproductions were made, fellow Declaration Committee member (and later second President of the United States) John Adams, changed the spelling to unalienable and this is the spelling used in the copy that is in the National Archives.

Text of the declaration

Template:Wikisourcepar The Preamble:

When in the Course of human events, it becomes necessary for one people to dissolve the political bands which have connected them with another, and to assume among the powers of the earth, the separate and equal station to which the Laws of Nature and of Nature's God entitle them, a decent respect to the opinions of mankind requires that they should declare the causes which impel them to the separation.

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness. -- That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed, -- That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness. Prudence, indeed, will dictate that Governments long established should not be changed for light and transient causes; and accordingly all experience hath shewn, that mankind are more disposed to suffer, while evils are sufferable, than to right themselves by abolishing the forms to which they are accustomed. But when a long train of abuses and usurpations, pursuing invariably the same Object evinces a design to reduce them under absolute Despotism, it is their right, it is their duty, to throw off such Government, and to provide new Guards for their future security. -- Such has been the patient sufferance of these Colonies; and such is now the necessity which constrains them to alter their former Systems of Government. The history of the present King of Great Britain is a history of repeated injuries and usurpations, all having in direct object the establishment of an absolute Tyranny over these States. To prove this, let Facts be submitted to a candid world.

- [List of charges against the King follows]

The conclusion and formal declaration: We, therefore, the Representatives of the united States of America, in General Congress, Assembled, appealing to the Supreme Judge of the world for the rectitude of our intentions, do, in the Name, and by the Authority of the good People of these Colonies, solemnly publish and declare, That these United Colonies are, and of Right ought to be Free and Independent States; that they are Absolved from all Allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the State of Great Britain, is and ought to be totally dissolved; and that as Free and Independent States, they have full Power to levy War, conclude Peace, contract Alliances, establish Commerce, and to do all other Acts and Things which Independent States may of right do. And for the support of this Declaration, with a firm reliance on the Protection of Divine Providence, we mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes and our sacred Honor.

Signatories of the declaration

The first and most famous signature on the Declaration was that of John Hancock, President of the Continental Congress. The other fifty-six signers of the Declaration represented the new states as follows:

- Robert Morris, Benjamin Rush, Benjamin Franklin, John Morton, George Clymer, James Smith, George Taylor, James Wilson, George Ross

- George Wythe, Richard Henry Lee, Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Harrison, Thomas Nelson, Jr., Francis Lightfoot Lee, Carter Braxton

1951PreservationOfDeclarationOfIndependenceByNBS.jpg

See also

- Declaration of independence

- History of the United States

- Virginia Declaration of Rights

- Karantania

- Strabane

- Life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness

- Wawrzyniec Grzymala Goslicki, whose book may have influenced Jefferson.

External links

- National Archives Declaration of Independence Page (http://www.nara.gov/exhall/charters/declaration/decmain.html)

- The Declaration of Independence: A History (http://www.archives.gov/national_archives_experience/charters/declaration_history.html) A National Archives page detailing the history of the physical document from conception to today.

- The Stylistic Artistry of the Declaration of Independence (http://www.archives.gov/national_archives_experience/charters/declaration_style.html) By Stephen E. Lucas - A thorough linguistic examination of the document.

The Preservation and History of the Declaration (http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/charters/)

"Drafting of the Declaration of Independence. The Committee: Franklin, Jefferson, Adams, Livingston, and Sherman." 1776. Copy of engraving after Alonzo Chappel. - credits National Archives and Records Administration (http://teachpol.tcnj.edu/amer_pol_hist/thumbnail31.html) -- large version (http://teachpol.tcnj.edu/amer_pol_hist/fi/0000001f.htm)

- Mural of the Declaration of Independence by John Trumbull (http://teachpol.tcnj.edu/amer_pol_hist/thumbnail32.html) -- *large version (http://teachpol.tcnj.edu/amer_pol_hist/fi/00000020.htm)

- Teaching about the Declaration of Independence (http://ericdigests.org/2003-4/independence.html)

- Declaration of Independence (http://www.generalatomic.com/AmericanHistory/declaration_of_independence.html)

- Video of Declaration of Independence being read (http://www.declareyourself.com/videos.htm) by Mel Gibson, Michael Douglas, Kevin Spacey, Whoopi Goldberg, Edward Norton, Benicio Del Toro, Ren�e Zellweger, Winona Ryder, Graham Greene (actor), Ming-Na, and Kathy Bates. Introduction is by Morgan Freeman.

- U.S. Independence celebrated on the wrong day? - National Geographic (http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2004/06/0629_040629_july4.html)

- Download High-resolution images of Declaration (http://www.archives.gov/national_archives_experience/charters/charters_downloads.html) From the National Archives

- Text of the Declaration of Independence (http://www.geocities.com/qubestrader/declaration.html)

- The fate of the original Declaration of Independence (http://www.artlebedev.ru/kovodstvo2/sections/113/) (Excellent illustrations,in Russian)