Tibetan people

|

|

Kham2.bmp

The Tibetan people are a people living in Tibet and some surrounding areas. They are one of the largest among the fifty-six nationalities officially recognized by the People's Republic of China (PRC) to constitute the Zhonghua Minzu (Chinese nation), although in anthropological terms they include more than one ethnic group. According to an official census of 1959, the number of Tibetans in the PRC was 6,330,567 [1] (http://www.tibet.com/WhitePaper/white8.html). The SIL Ethnologue documents an additional 125,000 speakers of Tibetan living in India, 60,000 in Nepal, and 4,000 in Bhutan.

| Contents |

Divisions

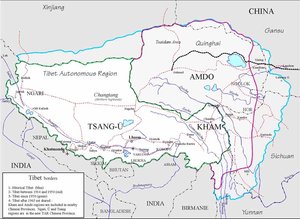

The Tibetan people are divided into several groups, which include the Changri, Nachan and Hor, who are further divided into fifty-one sub-tribes, each of them maintaining a distinct yet related cultural identity.

The Tibetans living in Kham are of Qiang descent and speak a Qiangic language, although they are not officially classified part of the Qiang minority. The Hor, who are further sub-divided into thirty-nine sub-tribes, are of Mongolian descent. The Tibetans in Qamdo are also known as the Khampa, while those in the far west and north are known as Poiba. Descendants of the Karjia are known as the Ando. Although the Tangut are now extinct as a distinct people, their descendants can be found among the Tibetans and Salar of Gansu.

TAR-TAP-TAC.png

Origins

It is generally agreed that Tibetans share a considerable genetic background with Mongols, although other main influences do exist. Some anthropologists have suggested an Indo-Scythian component, and others a Southeast Asian component; both are credible given Tibet's geographic location. The romantic claim that American Hopi and Tibetans are close cousins is not likely to find support in genetic studies, although strong cultural similarities may be found between the two groups.

Tibetans traditionally explain their own origins as rooted in the marriage of the bodhisattva Chenrezig and a mountain ogress. Tibetans who display compassion, moderation, intelligence, and wisdom are said to take after father, while Tibetans who are "red-faced, fond of sinful pursuits, and very stubborn" are said to take after mother.

There are two main ethnic groups in Tibet, in addition to the Han Chinese moved there in recent years by the PRC government. Central Tibetans (those living in the vast area around Lhasa, Ü-Tsang) obviously share a strong Mongolian component in their ancestry, whereas the tent-dwelling nomads of the high Tibetan plateau (known as Drokpa or, in Tibetan, Hbrog-pa, meaning "steppe-dwellers") and the "Khambas" in Kham are by comparison taller and longer-limbed, with sharper features and more aquiline noses. Some have suggested they are of Scythian descent. The Eastern Tibetans are not as mixed as the Central Tibetans in the sedentary areas. In Western Tibet, notably around Ladakh and Kashmir, people are closer to those of Indo-Aryan descent.

Notable features

Since the late 19th century, the Chinese presence in Eastern Tibet has increased, and often the Khambas there are bilingual. Still, mixed marriages between Tibetans and Chinese are not common.

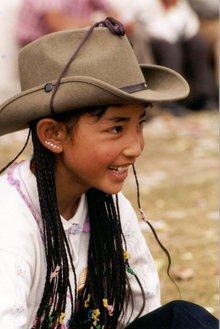

Tibetans typically have light brown skin, black, somewhat wavy or even curly hair, moderately high cheekbones, and brown eyes, although some have very light hazel or green eyes, due to their Mongol heritage. The men typically have full mustaches but sparse beards; traditionally, they pluck out their beards with tweezers. Nomads have long braided hair, and the women usually braid their hair in 108 braids.

Tibetans have a legendary ability to survive extremes of altitude and cold, an ability no doubt conditioned by the extreme environment of the Tibetan plateau. Recently, scientists have sought to isolate the cultural and genetic factors behind this adaptability[2] (http://www.cwru.edu/affil/tibet/HAN.html). Among their findings was a gene which improves oxygen saturation in hemoglobin, and the fact that Tibetan children grow faster than other children to the age of five (presumably as a defense against heat loss since larger bodies have a more favorable volume to surface ratio). The Tibet Paleolithic Project (http://paleo.sscnet.ucla.edu/TibetGroupPage.html) is studying the Stone Age colonization of the plateau, hoping to gain insight into human adaptability in general and the cultural strategies the Tibetans developed as they learned to survive in this harsh environment.

Religion

Three_monks_chanting_in_Lhasa,_1993.jpg

Tibetans generally observe Tibetan Buddhism and a close affiliate known as Bön, although pockets of Tibetan Muslims, known as Kache, can be found.

Legend said that the 28th king of Tibet, Lhatotori Nyentsen, dreamed of a sacred treasure falling from heaven, which contained a Buddhist sutra, mantras, and religious objects. However, owing to the fact that the modern Tibetan script was not introduced to the people, no one knew what was written on the sutra upon the first look. However, Buddhism did not take root in Tibet at that time.

It was not until during the reign of Songtsen Gampo, who married two Buddhist princesses, Tritsun and Wencheng, did Buddhism take root. It then gained popularity when Padmasambhava, widely known as Guru Rinpoche, visited Tibet at the intivation of the 38th Tibetan king, Trisong Deutson.

Today, one can see Tibetans placing Mani stones all over. Tibetan lamas, both Buddhist and Bön, play a major role in the lives of the Tibetan people, conducting religious ceremonies and taking care of the monasteries. Pilgrims plant their prayer flags onto the sacred grounds as a symbol of good luck.

The Dorje, or prayer wheel, is a sacred means of chanting the mantra by revolving the object several times in a clockwise direction, is widely seen among the Tibetans people. In order not to desecrate religious artefacts such as Stupas, mani stones and Gompas, Tibetan Buddhists walk around them in a clockwise direction, although the reverse direction is true for Bön. Tibetan Buddhists chant the prayer Om mani padme hum; while the practicioners of Bön chant a distinct mantra, Om matri muye sale du.

Culture

The Tibetan civilization boasts a rich culture. Tibetan festivals such as Losar, Xuedun, Linka and the Bathing Festival are deeply rooted in indigenous religion, and also contain foreign influences. Each person takes part in the Bathing Festival three times: at birth, at marriage, and at death. It is traditionally believed that people should not bathe casually, but only on the most important occasions.

Art

Tibetan art is deeply religious in nature, from the exquistely detailed statues found in Gompas to wooden carvings and the intricate designs of the Thangka paintings. Tibetan art can be found in almost every object and every aspect of daily life.

Thangka paintings, a syncrestism of Chinese scroll-painting with Nepalese and Kashmiri painting, appeared in Tibet around the 10th century. Rectangular and painted on cotton or linen, they are usually traditional motifs depicting religious, astrological, and theological subjects, and sometimes the Mandala. To ensure that the image will not fade, organic and mineral pigments are added, and the painting is framed in colorful silk broadcades.

Drama

The Tibetan folk opera, known as Ache llhamo, which literally means "fairy", is a combination of dances, chants and songs. The repertoire is drawn from Buddhist stories and Tibetan history.

The Tibetan opera was founded in the 14th century by Thangthong Gyalpo, a Lama and a bridge builder. Gyalpo and seven recruited girls organized the first performance to raise funds for building bridges, which would facilitate transportation in Tibet. The tradition continued, and llhamo is held on various festive occasions such as the Linka and Shoton festival.

The performance is usually a drama, held on a barren stage, that combines dances, chants and songs. Colorful masks are sometimes worn to identify a character, with red symbolizing a king and yellow indicating deities and lamas.

The performance starts with a stage purification and blessings. A narrator then sings a summary of the story, and the performance begins. Another ritual blessing is conducted at the end of the play.

Architecture

Tibetan architecture contains Chinese and Indian influences, and reflects a deeply Buddhist approach. The Buddhist wheel, along with two dragons, can be seen on nearly every Gompa in Tibet. The design of the Tibetan Chörtens can vary, from roundish walls in Kham to squarish, four-sided walls in Ladakh.

The most unusual feature of Tibetan architecture is that many of the houses and monasteries are built on elevated, sunny sites facing the south, and are often made out a mixture of rocks, wood, cement and earth. Little fuel is available for heat or lighting, so flat roofs are built to conserve heat, and multiple windows are constructed to let in sunlight. Walls are usually sloped inwards at 10 degrees as a precaution against frequent earthquakes in the mountainous area.

Standing at 117 meters in height and 360 meters in width, the Potala Palace is considered as the most important example of Tibetan architecture. Formerly the residence of the Dalai Lama, it contains over a thousand rooms within thirteen stories, and houses portraits of the past Dalai Lamas and statues of the Buddha. It is divided between the outer White Palace, which serves as the administrative quarters, and the inner Red Quarters, which houses the assembly hall of the Lamas, chapels, 10,000 shrines, and a vast library of Buddhist scriptures.

Medicine

Tibetan medicine is one of the oldest forms in the world, and utilizes up to 2,000 types of plants, 40 animal species and 50 minerals.

One of the key figures in its development was the renowned eighth century physician Yutok Yonten Gonpo, who produced the Four Medical Tantras integrating material from the medical traditions of Persia, India and China. The tantras contained a total of 156 chapters in the form of Thangkas, which tell about the archaic Tibetan medicine and the essences of medicines in other places.

Yutok Yonten Gonpo's descendant, Yuthok Sarma Yonten Gonpo, further consolidated the tradition with his addition of his 18 medical works. One of his books includes paintings depicting the resetting of a broken bone. In addition, he compiled a set of anatomical pictures of internal organs. Yuthok was considered the deity of medicine in the mortal world.

Life cycles

Traditionally, Tibetans believed in reincarnation, and religious ceremonies relating to birth and death are conducted at appropriate times. Many of these rituals stem from ceremonies of the ancient Bön religion.

In the birth ceremony, Pangsai, the relatives come together for a celebration and ritual. Gifts are presented to the parents and baby, including food, clothing, and the white Hada scarves. A pancake feast may also be prepared for the visitors. A high-ranking lama is also present to name the baby.

At death, Tibetans are given a "sky burial", which, they believe, will take the spirit of the dead safely to heaven.

Before the sky burial, the body is wrapped in a white cloth and kept in the house for several days while lamas chant sin-redeeming sutras. A red jar containing tsampa dough mixed with blood and other food products is decorated with a white hada and hung at the door of the house. The friends of the deceased also mourn, bringing pots of wine a day before the removal of the body.

On the day of the funeral, a body-cutter arrives to carry the deceased body up to the burial ground, with friends and a lama following closely behind. The body-cutter rips open the body of the deceased, then calls for the vultures.

Tibetans believe that the vultures have the power to bring the spirit of the body to heaven. In the event that the vultures do not eat, or only devour a portion of the body, then the person has committed sins and is doomed to hell. If the vultures devour every part of the body, or at least the majority of it, the soul rises to nirvana in a pure state. The skeleton is abandoned at the burial site.

Clothing

Most Tibetans wear their hair long, although in recent times some men do crop their hair short. The women plait their hair into two queues, while the girls into a single queue. Men who keep their hair long coil it on top of their heads, often wrapped in a red cloth that serves as a turban.

Because of Tibet's cold weather, women wear skirts and silk or cloth jackets. The men wear long, loose trousers, accompanied by a loose and sometimes sleveless gown, with a band at the top tied on the right, and woollen or leather boots. One or both sleeves on a garment are generally let off and tied around the waist. Herders sometimes wear sheepskin robes in place of the jacket. In addition, men wear long waistbands, and women wear colorful aprons.

Customs

Tibetans usually greet a friend or relative by saying "Tashi Delek", removing their hats, and bowing gently. However, when greeting an elderly man or respected person, they lower the hats to the floor as a sign of respect.

The 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article on Tibet reported that "among the customs of the Tibetans, perhaps the most peculiar is polyandry, the brothers in a family having one wife in common, mainly for the reason of avoiding the dividing of property."

"Monogamy, however," the article continued, "seems to be the rule among the pastoral tribes . . . ." Polygamy is also practiced by some, mainly by the Tibetans in Kham. Tibetan fraternal polyandry continues in recent times. Intermarriage with Han Chinese exists but is uncommon, as many ethnic Tibetans have negative sentiments towards the Han.

References

- Goldstein, Melvyn C., "Study of the Family structure in Tibet", Natural History, March 1987, 109-112 ([3] (http://web.archive.org/web/20030306141537/http://www.cwru.edu/affil/tibet/family.html) on the Web Archive).

External links

- Tibetan costume (http://www.china.org.cn/english/culture/96152.htm)

|

Chinese ethnic groups (classification by PRC government) |

|

Achang - Bai - Blang - Bonan - Buyei - Chosen - Dai - Daur - De'ang - Derung - Dong - Dongxiang - Ewenki - Gaoshan - Gelao - Gin - Han - Hani - Hezhen - Hui - Jingpo - Jino - Kazak - Kirgiz - Lahu - Lhoba - Li - Lisu - Man - Maonan - Miao - Monba - Mongol - Mulao - Naxi - Nu - Oroqen - Pumi - Qiang - Russ - Salar - She - Sui - Tajik - Tatar - Tu - Tujia - Uygur - Uzbek - Va - Xibe - Yao - Yi - Yugur - Zang - Zhuang |