Harpsichord

|

|

A harpsichord is the general term for a family of European keyboard instruments, including the large instrument nowadays called a harpsichord, but also the smaller virginals, the muselar virginals and the spinet. All these instruments generate sound by plucking a string rather than striking one, as in a piano or clavichord. The harpsichord family is thought to have originated when a keyboard was affixed to the end of a psaltery, providing a mechanical means to pluck the strings.

| Contents |

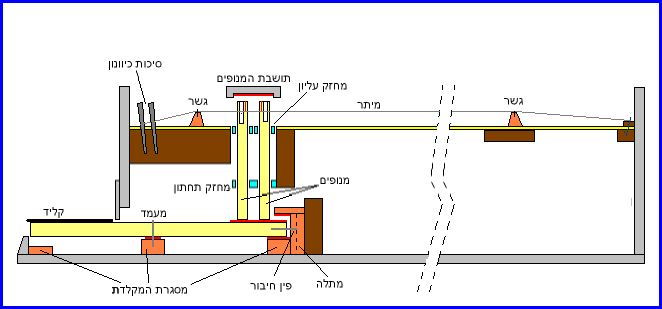

How harpsichords work

The action is fairly similar between all harpsichords:

- The keylever is a simple pivot which rocks on a pin passing through a hole drilled through it.

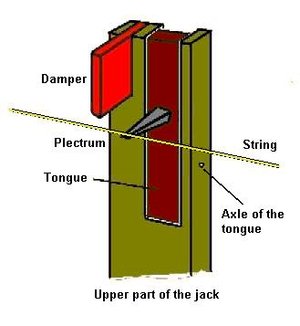

- The jack is a thin rectangular piece of wood which sits upright on the end of the keylever, held in place by the guides - upper and lower - which are two long pieces of wood with holes through which the jacks can pass.

- In the jack, a plectrum juts out almost horizontally, (normally the plectrum is angled upwards a tiny amount) and passes just under the string. Historically, plectra were normally made of crow quill, or leather, though most modern harpsichords use a plastic (delrin or celcon) instead.

- When the front of the key is pressed (2), the back is lifted up, the jack is raised, and the plectrum plucks the string (3).

Jack_action.PNG

- Upon lowering the key, the jack falls back down under its own weight, and the plectrum pivots backwards to allow it past the string (4). This is made possible by having the plectrum held in a tongue which is attached with a hinge and a spring to the body of the jack.

- At the top of the jack, a damper of felt sticks out and keeps the string from vibrating when the key is not depressed (1).

HPSCHD_shove_coupler.JPG

HPSCHD_dogleg_jack.JPG

Kinds of harpsichords

While the terms used to denote various members of the family are relatively standardized today, in the harpsichord's heyday, this was not the case.

Harpsichord

In modern usage, a harpsichord can either mean all the members of the family, or more specifically, the grand-piano-shaped member, with a vaguely triangular case accommodating long bass strings at the left and short treble strings at the right; characteristically, the profile is more elongated than that of a modern piano, with a sharper curve to the bentside. A harpsichord can have from one to three, and occasionally even more, strings per note. Often one is at four-foot pitch, an octave higher than the normal eight-foot pitch. Single manuals, or keyboards are common, especially in Italian harpsichords, though many other countries tended to produce double-manuals.

Virginals

The virginal or virginals is a smaller and simpler rectangular form of the harpsichord (that looks somewhat like a clavichord), with only one string per note running parallel to the keyboard on the long side of the case. The origin of the word is obscure but it is usually linked to the fact that the instrument was frequently played by young women. Note that the word "virginal" in Elizabethan times was often used to designate any kind of harpsichord; thus the masterworks of William Byrd and his contempories were often played on full-size Italian style harpsichords, and not just on the virginals as we call it today. Virginals are described either as spinet virginals (the usual type) or muselar virginals.

Spinet virginals

In spinet virginals, the keyboard is placed on the left, and the strings are plucked at one end, as in other members of the harpsichord family. This is the more common arrangement, and an instrument described simply as a "virginal" is likely to be a spinet virginal.

Muselar virginals

In muselar virginals, or muselars, the keyboard is placed to the right, so that the strings are plucked in the middle of their sounding length. This gives a warm and rich sound, but at a price: the action for the left hand is inevitably placed at the centre of the instrument's sounding board, with the result that any mechanical noise from this action is amplified. An eighteenth century commentator said that muselars "grunt in the bass like young pigs". In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, muselars were nonetheless popular, but they fell out of use in the eighteenth. In addition to mechanical noise, the central plucking point in the bass makes repetition difficult, because the motion of the still-sounding string interferes with the ability of the plectrum to connect again. Thus the muselar was better suited to chord-and-melody music, without complex left-hand parts.

Spinet

Finally, a harpsichord with the strings set at an angle to the keyboard (usually of about 30 degrees) is called a spinet. In such an instrument, the strings are too close to fit the jacks between them in the normal way; instead, the strings are arranged in pairs, the jacks are placed in the large gaps between pairs, and they face in opposite directions, plucking the strings adjacent to the gap.

Clavicytherium

A clavicytherium is a harpsichord that is vertically strung. Few were ever made. The same space-saving principle was later embodied in the upright piano.

Variations between harpsichords

Unsurprisingly, for an instrument that was produced in large numbers for over three centuries, there is a great deal of variation between harpsichords.

In addition to the varied forms that the instrument can take, and the different dispositions, or registrations, that can be fitted to a harpsichord, as mentioned above, the range can vary greatly.

Generally, earlier harpsichords have smaller ranges, and later ones larger, though there are frequent exceptions. In general, the largest harpsichords have a range of just over five octaves, and the smallest have under four. Usually, the shortest keyboards were given extended range using the method of the "short octave".

History of the harpsichord

The origin of the harpsichord is lost in the Middle Ages. The earliest written references to it date from the 1300's, and it is possible that harpsichord was indeed invented in that century. This was a time in which advances in clockwork and other forms of machinery were being made, and thus a likely time for the invention of those mechanical aspects that distinguish a harpsichord from a psaltery. A Latin manuscript work on musical instruments by Henri Arnault de Zwolle, c. 1440, includes detailed diagrams of a small harpsichord and three types of jack action.

The earliest complete harpsichords still preserved come from Italy, the oldest specimen being dated 1521. (The Royal Academy of Music, London, has an instrument of a curious upright form which may be older; unfortunately it lacks the action.) However, these early Italian instruments can shed no light on the origin of the harpsichord, as they represent an already well-refined form of the instrument. The Italian harpsichord makers made single-manual instruments with a very light construction and relatively little string tension. This design persisted with little alteration among Italian makers for centuries. The Italian instruments are considered pleasing but unspectacular in their tone, and serve well for accompanying singers or other instruments.

A revolution in harpsichord construction took place in Flanders some time around 1580 with the work of Hans Ruckers and his descendants, including Ioannes Couchet. The Ruckers harpsichord were more solidly constructed than the Italian. Because they used longer strings (always with the basic two sets of strings; either one 8' and a 4' or both at 8' pitch), greater string tension, and a heavier case, as well as a very slender and responsive spruce soundboard, the tone was more powerful and noble than with the Italian harpsichord, and served as the basis for subsequent harpsichord building in most other nations. The Flemish makers also innovated the two-manual harpsichord, which was initially used merely to permit easy transposition (at the interval of a fourth), rather than to increase the expressive range of the instrument. However, later in the 17th century the additional manual was also used for contrast of tone with the ability to couple the registers of both manuals for a fuller sound. The Flemish harpsichords were often elaborately painted and decorated.

The Flemish instrument received further development in 18th-century France, notably with the work of the Blanchet family and their successor Pascal Taskin. These French instruments imitated the construction of the Flemish ones, but they were extended in their range, from about four to about five octaves. In addition, two-manual French instruments used their manuals to vary the combination of stops being used (i.e., strings being plucked), rather than for transposition. The 18th century French harpsichord is often considered one of the pinnacles of harpsichord design, and it is widely adopted as a model for the construction of modern instruments.

A striking aspect of the 18th century French tradition was its near-fetishlike obsession with the Ruckers harpsichords. In a process called "grande ravalement", many of the surviving Ruckers instruments were torn apart and reassembled, with new soundboard material and case construction adding an octave to their range. It is considered likely that many of the harpsichords claimed at the time to be Ruckers restorations are fraudulent. From a contemporary point of view, these may be considered benevolent frauds, since they are superb instruments in their own right.

In England, two immigrant makers, Jacob Kirckman (from Alsace) and Burkat Shudi (from Switzerland) achieved eminence with harpsichords noted for their powerful tone and exquisite veneered cases. The sound of Kirckman and Shudi harpsichords has impressed many listeners, but the feeling that it overpowers the music has led to very few modern instruments being modeled on them. The Shudi firm was passed on to Shudi's son-in-law John Broadwood, who adapted it to the manufacture of the piano and became a leading creative force in the development of that instrument.

The German harpsichord makers roughly followed the French model, but with a special interest in achieving a variety of sonorities, perhaps because some of the most eminent German builders were also builders of organs. Some German harpsichords included a choir of two-foot strings (that is, strings pitched two octaves above the primary set). A few even included a 16-foot stop, pitched an octave below the main 8-foot choirs. One still-preserved German harpsichord even has three manuals to control all the many combinations of strings that were available. The 2-foot and 16-foot stops of the German harpsichord are not particularly in favor among harpsichordists today, who tend to prefer the French type of instrument.

At the peak of its development, the harpsichord lost favor to the piano. The piano quickly evolved away from its harpsichord-like origins, and as a result the knowledge of how to build good harpsichords died out for over a century.

In the early twentieth century, an awakening interest in authentic performance led to the revival of the harpsichord. This included crude "modernizations" of antique instruments, as well as the construction of harpsichords resembling modern concert grand pianos. These instruments sounded surprisingly weak for their size, because their frames and soundboards were too heavy to properly match the thin and lightly-tensioned strings of the harpsichord. Builders typically included a 16-foot stop in these instruments to bolster the sound, even though in historical times the 16-foot had played only a minor role.

Ultimately, it was realized that to make fine modern harpsichords it would be necessary to learn the methods followed by the old builders. Two important pioneers in the process of rediscovery were the builder-scholars Frank Hubbard and William Dowd, who took apart and inspected many old instruments and consulted the written material on harpsichords from the historical period. Today, harpsichords that are founded on the rediscovered principles of the old makers are built in workshops around the world. The workshops often also construct kits, which are assembled into final form by amateur enthusiasts.

Harpsichord music

The first music written specifically for solo harpsichord came to be published around the middle of the sixteenth century. Composers who wrote solo harpsichord music were numerous during the whole baroque era in Italy, Germany and, above all, France. Well into the eighteenth century, the harpsichord was considered to have advantages and disadvantages with respect to the piano. Besides solo works, the harpsichord is also well-suited to accompaniment in the basso continuo style (a function it maintained in opera even into the nineteenth century).

Through the 19th century, the harpsichord was ignored by composers, the piano having supplanted it. In the 20th century, however, with increasing interest in early music and composers on the lookout for new sounds, pieces began to be written for it once more. Concertos for the instrument were written by Francis Poulenc (the Concert champêtre), Manuel de Falla and, later, Henryk Górecki. Bohuslav Martinu wrote both a concerto and a sonata for it, and Elliott Carter's Double Concerto is for harpsichord, piano and two chamber orchestras. György Ligeti has written a small number of solo works for the instrument (including "Continuum"). More recently harpsichordist Hendrik Bouman has composed in the baroque style 32 solo pieces, 1 harpsichord Concerto and 2 compositions of chamber music with obligato harpsichord.

The Harpsichord also gained some popularity in light Jazz music during the 1960. Particularly in Britain. For example the Jazz theme tunes to the Avengers and Danger Man AKA Secret Agent TV programs from the 60s both feature Harpsichords. Also Lalo Shifrin sometimes featured harpsichords in his jazz recordings during the 1960s.

Harpsichordists

Musicians who play the harpsichord are known as harpsichordists. Modern harpsichord playing can be roughly divided into three eras, beginning with the career of the influential reviver of the instrument, Wanda Landowska (1879-1959). Landowska used a harpsichord made by Pleyel of the heavy, piano-influenced type discussed above. Such instruments, though now considered inappropriate for earlier music, retain some historical importance for the works that were specifically composed for them (concertos by Falla and Poulenc, for example). An influential later group of English players using post-Pleyel instruments by Thomas Goff and the Goble family included George Malcolm and Thurston Dart.

The next generation of harpsichordists were the pioneers of modern performance on instruments built according to the authentic practices of the earlier period, following the research of such scholar-builders as Frank Hubbard and William Dowd. This generation of performers included such players as Ralph Kirkpatrick, Igor Kipnis, and Gustav Leonhardt. More recently, many other outstanding harpsichordists have appeared, including Trevor Pinnock, Kenneth Gilbert, Christopher Hogwood, Ton Koopman, Christophe Rousset, and Andreas Staier.

For a list of harpsichord performers, see Harpsichordist.

See also

Baroque composers of solo harpsichord music

- Jean-Henri D'Anglebert

- Johann Sebastian Bach

- William Byrd

- Jacques Champion de Chambonnières

- François Couperin

- Louis Couperin

- Girolamo Frescobaldi

- Johann Jakob Froberger

- George Friderich Handel

- Louis Marchand

- Domenico Scarlatti

- Jean-Philippe Rameau

- Jean-Baptiste-Antoine Forqueray

Related instruments:

Miscellaneous related topics

Further reading

Three Centuries of Harpsichord Making by Frank Hubbard (1967, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; ISBN 0674888456) is an authoritative survey of how early harpsichords were built and how the harpsichord evolved over time in different national traditions.

External links

- A harpsichord site with images (http://www.bigduck.com/harp1.html)

- Hear the sound of various harpsichords (http://www-personal.umich.edu/~bpl/hpsi.html)

- A web ring of harpsichord and clavichord sites (http://d.webring.com/hub?ring=hpsiclavi)

- Latin mottoes painted on harpsichords (http://www.bigduck.com/mottos.html)

- Extensive source of harpsichord information (http://www.harpsichord.org.uk)da:Cembalo

de:Cembalo eo:Klaviceno es:Clavicémbalo fi:Cembalo fr:Clavecin it:Clavicembalo ja:チェンバロ nl:Klavecimbel pl:Klawesyn pt:Cravo sl:Čembalo sv:Cembalo zh:羽管é®ç´