Newark, New Jersey

|

|

Newark (), nicknamed The Brick City, is the largest city in New Jersey and the county seat of urban Essex County. Located approximately five miles (8 km) west of Manhattan, its location near the Atlantic Ocean on Newark Bay has helped make its port facility, Port Newark, the major container shipping port for New York Harbor. It is the home of Newark Liberty International Airport (formerly Newark Airport) which was the first major airport to serve the New York metropolitan area.

DSCN3830_newarkskylinefrombridge_ef.JPG

| Contents |

History

Main article: History of Newark, New Jersey

P1170169.JPG

Newark was founded in 1666 by Connecticut Puritans led by Robert Treat, making it the third-oldest major city in the United States, after Boston and New York, though it is not the third-oldest settlement. Newark is the city's third name; previously, it was called Pasaic Town and New Milford. The name comes from Newark-on-Trent, a town in England from where some of the original settlers arrived.

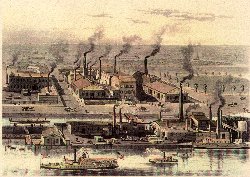

Newark's rapid growth began in the early 1800s through the making of patent leather and the construction of the Morris Canal in 1831. The canal connected Newark with the New Jersey hinterland, at that time a major iron and farm area. In 1826, Newark's population stood at 8,017, ten times the 1776 number. (Newark, John T. Cunningham, Chap. 11, Chap. 18)

In the middle of the 19th century, Newark's industrial base diversified into Celluloid, the first commercially successful plastic, which found its way into Newark-made carriages, billiard balls, and dentures. Thomas Edison himself made Newark home in the early 1870s, inventing the stock ticker in the Brick City (Ibid, Chap. 18, pg 181). Nor was Newark entirely industrial. In the middle 19th century, Newark added insurance to its repertoire of businesses; Mutual Benefit was founded in the city in 1845 and Prudential in 1873. Today, Newark sells more insurance than any city except Hartford, Connecticut. (Ibid, Chap. 19, pg 186)

Newark was bustling in the early to mid 20th century. It had four flourishing department stores – Hahne & Company, L. Bamberger and Company, L.S. Plaut and Company, and Kresge's (later known as K-Mart). "Broad Street today is the Mecca of visitors as it has been through all its long history," Newark merchants boasted, "they come in hundreds of thousands now when once they came in hundreds." (Newark, pg. 195) In 1948, just after World War II, Newark hit its peak population of just under 450,000.

Post-WWII era

But underneath the industrial hum, problems existed. Most New Jerseyans attribute Newark's demise to post-WWII phenomena—the 1967 riots, the construction of the New Jersey Turnpike, I-280 and I-78, decentralization of manufacturing, the GI Bill, and the general pro-suburban fiscal order—but Newark's relative decline actually began long before that. The city budget fell from $58 million in 1938 to only $45 million in 1944, despite the wartime boom and an increase in the tax rate from $4.61 to $5.30. Even in 1944, before anyone predicted the rise of the Sun Belt or the GI Bill, planners saw problems on Newark's horizon.

Some attribute Newark's downfall to building so many housing projects, however, Newark's housing was always a matter of concern. The 1944 city-commissioned study showed that 31% of all Newark dwelling units were below standards of health, and only 17% of Newark's units were owner-occupied. (Newark, Chap. 27)

Despite its problems, Newark did try in the postwar era. Prudential and Mutual Benefit were successfully enticed to stay and build new offices, and Rutgers University-Newark and Seton Hall University expanded their Newark presences, with the former building a brand-new campus on a 23 acre (93,000 m²) urban renewal site. The Port Authority of New York and New Jersey made Newark the first container port in the nation and turned swamps in the south of the city into one of the ten busiest airports in the United States.

As pesticides and mechanization reduced the need for cheap labor in the South, five million blacks migrated to northern cities between 1940 and 1970s, Newark being no exception. From 1950 to 1960, while Newark saw its overall population drop from 438,000 to 408,000, it gained 65,000 non-whites. By 1966, Newark was majority black, a faster turnover than most other northern cities experienced. In the 1950s alone, Newark's white population decreased from 363,000 to 266,000. From 1960 to 1967 its white population fell a further 46,000. Though white flight changed the complexion of Newark residents, white flight did not change the complexion of political and economic power in the city. In 1967, out of a police force of 1400, only 150 members were black, mostly in subordinate positions. The whiteness and brutality of the police force led it to be seen as an occupying force, rather than a protective entity. Since Newark's blacks lived in neighborhoods that had been white only two decades before, nearly all of their apartments and stores were white-owned as well. In 1967, when 70% of Newark's students were black, Mayor Hugh Addonizio refused to appoint a black secretary to the Board of Education. More importantly, Mayor Addonizio offered, without consulting any residents of the neighborhood to be affected, to condemn and raze for the University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey 150 acres (607,000 m²) of a densely populated black neighborhood in the central ward. (UMDNJ had wanted to settle in suburban Madison.)

The poverty and lack of political power contributed to a growing radicalization of Newark's black population. On July 12, 1967 there were scuffles between blacks and police in the fourth ward, but damage for the night was only $2,500. However, following television news broadcasts on July 13, new, larger riots took place. Twenty-six people were killed, 1,500 wounded, 1,600 arrested, and $10 million in property destroyed. More than a thousand businesses were torched or looted, including 167 groceries, most never to reopen. Newark's reputation suffered dramatically. Tens of thousands of whites moved out. Middle class areas like Weequahic went from middle class white to poor black seemingly overnight. It was said "wherever American cities are going, Newark will get there first."

Post-riots

Riots.jpg

NewarkRiot-Area.jpg

Nevertheless, Newark’s downtown saw growth in the post-riot decades. Less than two weeks after the riots, Prudential announced plans to underwrite a $24 million office complex near Penn Station – dubbed "Gateway." Today the Gateway hosts thousands of white-collar workers, though few live in Newark, and the buildings themselves were not designed with consideration for pedestrians.

Before the riots, there had been an issue over where the University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey would be built, the suburbs or Newark. The riots, and Newark's undeniable desperation, made definite that the medical school would be in Newark. However, instead of being built on 167 acres (676,000 m²), the medical school would be built on just 60, part of which was already city owned.

Newark had elected one of the first African-American mayors in the nation in 1970, Kenneth Gibson, and the 1970s was a time of battles between Gibson and the shrinking white population. In North Newark, Anthony "Tough Tony" Imperiale represented the white backlash. Imperiale initially won fame by organizing the defense of the North Ward during the riots, and had an unsuccessful run at the mayorship.

Today

Newark-broad-street.jpg

Newark elected a new mayor in 1986, Sharpe James. James has been a tireless promoter of the city in the media and in the state Senate, but he is criticized for his high salary (over $200,000 a year) and the corruption that he tolerates. James is also criticized by opponents of the new New Jersey Devils arena who argue that $200 million is far too much for a city as poor and small as Newark to pay for a one-sport venue.

In the 1990s Newark benefited from the soaring national economy and from huge increases in state aid for education. The city successfully attracted several high-tech concerns with its state of the art fiber optic network. Since 2000 Newark has actually gained population, its first increase since the 1940s. In 2004 its crime rate decreased 56%.

Culture

P7140087.JPG

Downtown Newark is not laid out on a grid, giving the downtown area character. There are several notable Beaux-Arts buildings, such as the Veterans' Administration building, the Newark Museum, the Newark Public Library, and the Cass Gilbert designed Essex County Courthouse. Notable Art Deco buildings include several 1920s era skyscrapers, like 1180 Raymond Boulevard, the intact Newark Penn Station, and Arts High School. Gothic architecture can be found at the Cathedral of the Sacred Heart by Branch Brook Park which is one of the largest gothic cathedrals in the United States. It is rumoured to have as much stained glass as the Cathedral of Chartres. Newark has two public sculpture works by Gutzon Borglum — Wars of America in Military Park and Seated Lincoln in front of the Essex County Courthouse.

P7140079.JPG

The Newark Museum's American art collection is first class, and its Tibetan collection is considered one of the best in the world. Through September 4th, the Newark Museum has a special exhibition on the art and dresses of weddings. Newark is also home to the New Jersey Historical Society, which has rotating exhibits on New Jersey and Newark. The New Jersey Historical Society's exhibits through mid-2005 are on tuberculosis, Ellis Island, and on a black nightclub called "Dreamland." The Newark Public Library also produces a series of fascinating historical exhibits. Their current exhibit is on the cemetery art of New Jersey.

In February 2004, plans were announced for a new Smithsonian-affiliated Museum of African-American Music to be built in the city's Lincoln Park neighborhood. The museum will be dedicated to black musical styles, from gospel to rap. The new museum will incorporate the facade of the old South Park Presbyterian Church, where Abraham Lincoln once spoke. Groundbreaking is planned for winter 2006 and the grandopening will be in 2007.

Plans were formalized in November of 2004 for a New Jersey Jewish Museum at Temple Ahavas Shalom, in the Broadway neighborhood, the last synagogue in Newark. The museum will memorialize the Jewish community of Newark, which once numbered 60,000 and had fifty shuls.

Newark is also proceeding with plans for an arena for the New Jersey Devils.

Newark is the home of Rutgers University (Newark Campus); the New Jersey Institute of Technology (NJIT); Seton Hall University's School of Law; the University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey (Newark Campus); and Essex County College. Most of Newark's academic institutions are located in the city's University Heights district. Rutgers-Newark and NJIT are in the midst of major expansion programs, including plans to purchase surrounding buildings and revitalize current campuses. More students are requesting to live on campus and the universities have plans to build and expand several dorms. Such overcrowding is contributing to revitalization of nearby apartments. Nearby restaurants primarily serve college students and well lit, frequently policed walks have been organized by the colleges to encourage students to venture downtown as well.

Interestingly enough, Newark has produced more influential rap artists than one would expect from a city of Newark’s size. Queen Latifah, The Fugees, Naughty by Nature, and Redman all came from Newark or neighboring East Orange and South Orange, as did several lesser known hip-hop artists such as Jaheim, Faith Evans, and Joe. Also, from 1947 until the mid-1990s, Herman Lubinsky's influential jazz label, Savoy Records, was located at 58 Market Street in downtown Newark.

Neighborhoods

Main article: List of neighborhoods in Newark, New Jersey

As New Jersey's largest and second-most-diverse (after neighboring Jersey City) city, Newark's neighborhoods are flavored with people from various backgrounds, including African-Americans, Italians, Jews, various Latinos such as Brazilians, Ecuadorians, Haitians, and the largest Portuguese population of any American city. The city is divided into five political wards - North, South, East, West, and Central - that encompass some 15 neighborhoods.

Geography

Newarklocator.jpg

The official City of Newark, New Jersey web site gives the following information:

- Area, 24.14 square miles (63 km²). Smallest land area among 100 most populous cities in U.S.

- Altitude, 0 to 273.4 feet (83 m) above sea level; average, 55 feet (17 m).

- Latitude, 40o44'14". Longitude, 74o10'55". [1] (http://www.ci.newark.nj.us/About_Newark/Fast_Facts/Geography.htm)

Demographics

As of the censusTemplate:GR of 2000, there are 273,546 people. The population density is 11,400/mile² (4,400/km²), or 21,000/mile² (8,100 km²) once airport, railroad, and seaport lands are excluded, one of the highest in the nation.

The racial makeup of the city is 26.52% White or Euro-American, 53.46% Black or African American, 0.37% Native American, 1.19% Asian, 0.05% Pacific Islander, 14.05% from other races, and 4.36% from two or more races. 29.47% of the population are Hispanic or Latino of any race. There is a significant Portuguese-speaking community, made up by Brazilian and Portuguese ethnicities, concentrated mainly at the Ironbound neighborhood.

There are 91,382 households out of which 35.2% have children under the age of 18 living with them, 31.0% are married couples living together, 29.3% have a female householder with no husband present, and 32.2% are non-families. 26.6% of all households are made up of individuals and 8.8% have someone living alone who is 65 years of age or older. The average household size is 2.85 and the average family size is 3.43.

In the city the population is spread out with 27.9% under the age of 18, 12.1% from 18 to 24, 32.0% from 25 to 44, 18.7% from 45 to 64, and 9.3% who are 65 years of age or older. The median age is 31 years. For every 100 females there are 94.2 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there are 91.1 males.

Newark is the most populated city in New Jersey.

The median income for a household in the city is $26,913, and the median income for a family is $30,781. Males have a median income of $29,748 versus $25,734 for females. The per capita income for the city is $13,009. 28.4% of the population and 25.5% of families are below the poverty line. Out of the total population, 36.6% of those under the age of 18 and 24.1% of those 65 and older are living below the poverty line.

Business

Newark has over 300 types of businesses including 1,800 retail and 540 wholesale establishments, eight major bank headquarters, including those of New Jersey's three largest banks, and twelve savings and loan association headquarters. Deposits in Newark-based banks are over $20 billion.

Newark is the third-largest insurance center in U.S., after New York and Hartford. Prudential Insurance and Mutual Benefit Companies originated and the former is still headquartered in Newark. Prudential is the largest insurance company in the world.

Newark is not the industrial colossus of yesteryear, but the city does have a considerable amount of industry. The southern portion of the Ironbound, also known as the Industrial Meadowlands, has seen many factories built since World War II, including a large brewery.

Other facts

Pioneer radio station WOR AM was originally licensed to and broadcast from the Bamberger's Department Store in Newark.

Newark was Paul Simon's and Wayne Shorter's birthplace. Rapper Redman is from Newark, and has written many raps about Newark, including "Welcome 2 Da Bricks" on his Doc's Da Name 2000 album. Film director Brian De Palma was born and lives in Newark.

The City of Newark is presently governed under the Faulkner Act (Mayor-Council) system of municipal government.

References

- Cunningham, John T. Newark. New Jersey Historical Society

- Immerso, Michael. Newark's Little Italy: The Vanished First Ward. Rutgers University Press

- Stummer, Helen M. No Easy Walk: Newark, 1980-1993. Temple University Press

External links

- The City of Newark, New Jersey (http://www.ci.newark.nj.us/About_Newark/About_Newark.htm)

- Map of Newark (http://www.gonewark.com/atWork/CityMaps/documents/city_map2003_FP.pdf)

- Go Newark (http://www.gonewark.com/) - Guide to news, culture, history, and leisure activities in and around Newark.

- Newark History (http://www.ci.newark.nj.us/About_Newark/About_Newark.htm)

- Old Newark (http://www.oldnewark.com/)

- Newark News (http://www.nj.com/columns/ledger)

- Newark City Subway (http://www.nycsubway.org/nyc/newark/) - Overview and history of the subway.

- New Jersey Performing Arts Center (http://www.njpac.org/)

- Newark Public Library (http://www.npl.org/)

- New Jersey Historical Society (http://www.jerseyhistory.org/)

- Article: Newark rated #9 major city for business by INC (http://www.inc.com/magazine/20040301/top25.html)

- Article: Village Voice on Newark (http://www.villagevoice.com/issues/0411/jacobi.php)

- US Census Bureau - Newark - QuickFacts (http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/34/3451000.html)

| Regions of New Jersey |

|

| Jersey Shore | Meadowlands | North Jersey | Pine Barrens | South Jersey | New York metropolitan area | Delaware Valley | |

| Largest cities | |

|

Atlantic City | Bayonne | Camden | Clifton | East Orange | Elizabeth | Hackensack | Hoboken | Jersey City | Linden | Long Branch | New Brunswick | Newark | Passaic | Paterson | Perth Amboy | Plainfield | Trenton | Union City | Vineland | |

| Counties of New Jersey | |

|

Atlantic | Bergen | Burlington | Camden | Cape May | Cumberland | Essex | Gloucester | Hudson | Hunterdon | Mercer | Middlesex | Monmouth | Morris | Ocean | Passaic | Salem | Somerset | Sussex | Union | Warren |

bg:Нюарк da:Newark de:Newark (New Jersey) et:Newark es:Newark, Nueva Jersey fr:Newark (New Jersey) ja:ニューアーク (ニュージャージー州) pl:Newark (miasto w New Jersey) pt:Newark (Nova Jérsia) zh:紐華克