Louis XV of France

|

|

| Missing image Louis15-4.jpg Louis XV King of France and Navarre |

Louis XV (February 15, 1710 – May 10, 1774), called the Well-Beloved (French: le Bien-Aimé), was King of France from 1715 to 1774. Miraculously surviving the death of his entire family, he was loved by the French at the beginning of his reign. However, in time, his inability to reform the French monarchy and his policy of appeasement on the European stage lost him the support of his people, and he died one of the most unpopular kings of France.

Louis XV is the king with the most ambivalent personality in the history of France. Though he has been much maligned by historians, modern research shows that he was in fact very intelligent and dedicated to the task of ruling the largest kingdom of Europe. However, his indecisiveness, fueled by his awareness of the complexity of problems ahead, as well as his profound timidity, hidden behind the mask of an imperious king, account for the poor results achieved during his reign. In many ways, Louis XV prefigures the bourgeois rulers of the romantic 19th century: although dutifully playing the role of the imperial king carved out by his great-grandfather Louis XIV, Louis XV in fact cherished nothing more than his private life far away from pomp and ceremony. Having lost his mother while still an infant, he always longed for a motherly and reassuring presence, which he tried to find in the intimate company of women, for which he was much slandered both during and after his life.

| Contents |

The Miracle Child

LouisXVchild.jpg

Louis XV was born at Versailles on February 15, 1710, while his great-grandfather Louis XIV was still on the throne. He was the son of Louis, Duke of Burgundy and of Marie-Adélaïde of Savoy. Marie-Adélaïde was a very lively woman of whom the old king Louis XIV was very fond, and the young couple, deeply in love with each other (quite an unusual fact at the court in Versailles), had rejuvenated the court of the old king and become the centre of attraction in Versailles. Louis XV had a brother, Louis, Duke of Brittany, who was older by three years. The Duke of Burgundy was the eldest son of Louis, the Grand Dauphin, who was the only son of Louis XIV. The Duke of Burgundy had two younger brothers: Charles, Duke of Berry, and Philip, Duke of Anjou, soon to be confirmed as Philip V of Spain. Thus, by 1710, Louis XIV had plenty of male descendants: one son, three grandsons, and two great-grandsons from his oldest grandson.

However, dramatic events altered the shape of the royal family. In 1700, the Duke of Anjou had become King of Spain under the name Philip V, inheriting the crown from his grandmother, wife of Louis XIV and a Spanish princess. In the War of the Spanish Succession that had followed, Philip V had had to renounce all claims to the French throne. England was loath to see Spain and its colonial empire united with France under a single king in the future. The renunciation of Philip V was not a major problem for Louis XIV since he had so many other male descendants. However, in April 1711 the Grand Dauphin died suddenly, and the Duke of Burgundy became heir to the throne. Then one year later, the vigorous and lively Marie-Adélaïde of Savoy contracted smallpox (or measles) and died on February 12, 1712, to the dismay of the old king Louis XIV. The Duke of Burgundy, heartbroken by the death of his wife, died within a week of the same disease. Within a week of the Duke of Burgundy's death, it was also clear that the two children of the couple had caught the virus. The eldest son, the Duke of Brittany, was bled repeatedly by doctors and died on March 8, 1712. His younger brother Louis XV was saved by his governess Madame de Ventadour, who vigorously forbade doctors to bleed the young boy and personally looked after him during his illness. Then finally in 1714 the Duke of Berry, second son of the Grand Dauphin, died.

Thus Louis XIV had lost four male descendants in just three years, and the fate of the dynasty now lay in the survival of a four-year-old boy. Should the boy die, the crown would pass to Philippe d'Orléans, the nephew of Louis XIV, and first cousin of the late Grand Dauphin. However, it appeared quite probable that Philip V of Spain would denounce the treaty whereby he had renounced the crown of France, and that a major European war, as well as a French civil war, was sure to happen. The young four-year-old boy was made very conscious of the heavy responsibility lying on his shoulders, and his life was carefully watched every single minute. Moreover, the young boy was now an orphan, with no surviving siblings, no uncles or aunts (except Philip V who was in Madrid and whom he would never meet), and no first cousins (again, excepting those in Madrid). This family context shaped much of the later personality of the king.

The Regency of the Duke of Orléans

Regent-Philippe.JPG

Towards the end of August 1715, Louis XIV was dying of gangrene. On August 26 he called his five-year-old great-grandson Louis to his bedside and spoke to him, saying these famous words: "My child, you are going to be a great king. Do not imitate me in my liking for buildings and for wars. On the contrary, do try to have peace with your neighbors. Give to God what you owe him. Always follow good advice. Do try to relieve the suffering of your people, which I am most distressed at not having been able to do." Six days later, the man who had ruled France for more than 50 years died, and Louis XV was immediately greeted as the new King of France.

Distrustful of his nephew Philippe d'Orléans, Louis XIV in his will had named his bastard son Louis, Duke of Maine as the Regent for the young Louis XV. However, on September 2, one day after the death of the king, as the Parlement of Paris convened to proclaim the regency, Philippe d'Orléans made a deal with the parliamentarians, granting them the power to veto royal edicts, which had been withdrawn from them by Louis XIV, and so he had the will of the late king declared null and void. Philippe, now 41 years old, was officially made regent by the Parlement, in a court coup recorded in detail by Saint-Simon. The regent took the symbolic decision to relocate the government to Paris, and the court in Versailles disbanded.

The regent conducted affairs of state from his Parisian palace, the Palais Royal. The young Louis XV was moved to the modern lodgings attached to the medieval fortress of Vincennes, located 7 km/4.5 miles east of Paris in the Forest of Vincennes, where the air was deemed more wholesome and healthy than in Paris. Later during the regency he was moved to the Tuileries Palace, in the center of Paris, near the Palais Royal.

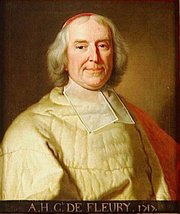

In 1717, the seven-year-old king was separated from his governess Madame de Ventadour, and put in the care of the Duke of Maine, superintendent of his education, aided by André-Hercule de Fleury (later to become Cardinal de Fleury), tutor to the young king, and the Duke of Villeroi, governor to the young king. The Duke of Villeroi, an old and vain courtier, loved to show the good manners and talents of his pupil. The young king, during endless public ceremonies, had to learn to hide his feelings and his natural shyness. He acquired the cold attitude and air of majesty that he would display during his entire life in public, as well as a taste for private apartments and intimate circles - in short an almost private bourgeois lifestyle.

Fleury, his tutor, gave him an excellent education, with renowned professors such as the geographer Guillaume Delisle. Louis XV had an extremely curious and open-minded personality. He was an avid reader, of eclectic tastes. A man of the Enlightenment, fond of science and new technologies, he pushed for the creation of a department of physics (1769) and mechanics (1773) at the Collège de France. The Cardinal de Fleury, an ambitious man, and, like the king, secretive, but above all affable, was deeply admired by Louis XV, and had a great influence on the rest of the king's life.

During the Régence, the Regent, Philippe d'Orléans, in search of support, favoured the nobility (aristocrats) who had been deprived of power during the reign of Louis XIV. He established the so-called polysynody (September 15, 1715), which allowed the aristocracy to participate in the government. He concluded an alliance with Great Britain in 1717 (Triple Alliance) in an effort to prevent Philip V of Spain from claiming the crown of France should the young Louis XV die. Confronted with a total lack of expertise amongst the aristocracy in government affairs, the Regent reverted to the monarchical organization of government that existed under Louis XIV and by 1718 had reinstated secretaries of state. Cardinal Dubois, close confident of the Regent, was made prime minister in 1722. In an attempt to replenish the French treasury the regency tried a number of original financial experiments, notable amongst which was the famous financial system of John Law, a financial bubble which ended up in bankruptcy and brought about the ruin of many aristocrats.

In 1721, Louis XV was betrothed to his first cousin, Marie-Anne-Victoire, daughter of Philip V of Spain. The eleven-year-old king found no interest in the arrival in Paris of his future wife, the three-year-old Spanish infanta, who only caused boredom in him. In June 1722 the young king and the court returned to Versailles, where they would stay until the end of the reign. In October of the same year, Louis XV was officially crowned in Reims Cathedral. On February 151723, as he turned thirteen, the king was declared of majority by the Parlement of Paris, thus ending the Régence. The King left the Duke of Orléans in charge of state affairs. The Duke of Orléans was made prime minister on the death of Cardinal Dubois in August 1723, and he himself died in December of the same year. Following the advice of Fleury, Louis XV appointed his cousin the Duke of Bourbon, Prince of Condé, to replace the late Duke of Orléans.

The Ministry of the Duke of Bourbon

The king took no part in the decisions of the government under the Duke of Bourbon. The government was secretly under the influence of a group of speculators and wheeler-dealers such as É. Berthelot de Pléneuf and banker J. Pâris-Duverney.

The Duke of Bourbon was worried by the health of the young king, not so much out of concern for the king or the future of the dynasty, but in fact out of a desire to prevent the House of Orléans (of the late Regent) from ascending the throne should the king die. The Duke of Bourbon saw the House of Orléans as his enemy. The king was quite frail, and several alerts led to concern for his life. The Spanish infanta was too young to procreate and give an heir. Thus, the Duke of Bourbon, who was also hostile to Spain, sent the infanta back to Spain and set about choosing a European princess old enough to produce an heir. Eventually, the choice fell on 21-year-old Marie Leszczyńska, daughter of Stanislaus I of Poland, the toppled King of Poland. A poor princess who had followed her father's misfortunes, she was nonetheless said to be virtuous, and quite charming. She was also from a royal family who had never interbred with the French royal family, and it was hoped that she would bring new blood into the French royal family. The relatively low status of her father would also ensure that the marriage would not cause diplomatic embarrassment to France by having to choose one royal court over another. The marriage was celebrated in September 1725. The young king immediately fell in love with his new wife, who was seven years older than he. Nonetheless, the marriage of the most powerful king in Europe with such a low-ranking princess was considered to be improper and lacking in grandeur by most of Europe.

The ministry of the Duke of Bourbon was marked by the persecution of Protestants (1726), several monetary manipulations, the creation of new taxes such as the fiftieth (cinquantième) in 1725, and the high price of grain, all of which created troubles and economic depression.

In 1726, the king, who was now sixteen and had had since his marriage a new health and authority that everyone at court had noticed, dismissed the Duke of Bourbon, who was extremely unpopular and was preparing a war against Spain and Austria. As his replacement he chose his old tutor, Cardinal de Fleury, to serve as prime minister.

The Ministry of Cardinal de Fleury

From 1726 until his death in 1743, Cardinal de Fleury ruled France with the king's assent. It was the most peaceful and prosperous part of the reign of Louis XV, despite some Parliamentarian and Jansenist unrest. After the financial and human losses suffered at the end of the reign of Louis XIV, the rule of Fleury, generating peace and order, is seen by historians as a period of "recovery" (French historians talk of a gouvernement "réparateur"). It is hard to determine exactly which part the king took in the decisions of the Fleury government, but what remains certain is that the king steadily supported Fleury against the intrigues of the court and the conspiracies of ministers.

With the help of controllers-general of finances Michel Robert Le Peletier des Forts (1726-1730) and above all Philibert Orry (1730-1745), Fleury stabilized the French currency (1726) and eventually managed to balance the budget in 1738. Economic expansion was also a central goal of the government: communications were improved, with the completion of the Saint-Quentin canal (linking the Oise and Somme rivers) in 1738, later extended to the Escaut River and the Low Countries, and above all with the systematic building of a national road network. The body of ponts et chaussées engineers, instituted by the central state, built modern straight highways starting in Paris and reaching the far-away borders of France, in the typical star pattern that is still the backbone of the National Highway network of France today. By the middle of the 18th century, France had the most modern and extensive road network in the world, with most of these highways still used today by automobile traffic. Maritime trade was also stimulated by the Bureau and the Council of Commerce, and the French foreign maritime trade increased from 80 to 308 million livres between 1716 and 1748. However, rigid Colbertist laws (prefiguring dirigisme) hindered industrial development.

The power of the absolute monarchy was demonstrated with the quelling of the Jansenist and Gallican oppositions. The troubles caused by the convulsionaries of the Saint-Médard graveyard in Paris (a group of Jansenists pretending that miracles took place in this graveyard) were put to an end in 1732. On the other hand, after the "exile" of 139 Parliamentarians in the provinces, the parlement of Paris had to register the Unigenitus papal bull and was forbidden to hear religious cases in the future.

Abroad, Fleury sought peace at all cost, averse as he was to wars. His peace policy was based on an English alliance and the reconciliation with Spain. In September 1729, at the end of her third pregnancy, the queen finally gave birth to a male child, Louis, dauphin de France, who immediately became heir to the throne. The birth of a long awaited heir, which ensured the survival of the dynasty for the first time since 1712, was welcome with tremendous joy and celebrations in all spheres of French society, and indeed in most European courts. The royal couple was at the time very united and in love of each other, and the young king was extremely popular. The birth of a male heir also dispelled the risks of a succession crisis and the likely war with Spain that would have resulted.

In 1733, despite Fleury's peace policy, the king, won over by his Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs Germain Louis Chauvelin (1727-1737), intervened in the War of the Polish Succession in an attempt to restore his father-in-law Stanislaus Leszczynski on the Polish throne. France also hoped to secure the long coveted duchy of Lorraine from its duke Francis III, who was expected to marry Holy Roman Emperor Charles VI's daughter, Maria Theresa, which would bring Austrian power dangerously close to the French border. The half-hearted French intervention in the east was unable to reverse the course of the war, and Stanislaus could not recover his throne. In the west, however, French troops rapidly overran Lorraine, and peace was restored as early as 1735. By the Treaty of Vienna (November 1738), Stanislaus was compensated for the loss of his Polish throne with the duchy of Lorraine, which was scheduled to pass to France on his death (through his daughter), while Duke Francis III of Lorraine was made heir to the Grand Duchy of Tuscany. The war cost very little to France, compared to the financial and human drains of Louis XIV's wars, and was a clear success for French diplomacy. The acquisition of Lorraine (effective in 1766 at Stanislaus' death) was to be the last territorial expansion of France on the continent before the French Revolution.

Shortly after this favorable result, France's mediation in the war between the Austrian Empire and the Ottoman Empire led to the Treaty of Belgrade (September 1739) which ended the war in favor of the Ottoman Empire, a traditional ally of France against the Habsburgs (since the early 16th century). As a result, in 1740 the Ottoman Empire renewed the French capitulations, which marked the supremacy of French trade in the Middle East. After all these successes, the prestige of Louis XV, arbiter of Europe, was at its highest.

In 1740, the death of Emperor Charles VI and his succession by his daughter Maria Teresa started the European War of the Austrian Succession. The old cardinal de Fleury did not have enough energy left to oppose the war, and the king gave in to the strong pressure of the anti-Austrian party at court: he entered the war in 1741 by allying with Prussia. The war would last seven long years. France was renewing with the cycle of wars so typical of Louis XIV's reign. Fleury, however, did not live to see the end of the war, and died in January 1743. The king, following at last the example of his predecessor Louis XIV, decided henceforth to rule without a prime minister, thus starting his personal reign.

First attempts at reform

Louis XIV had left France in a financial mess and in a general decline. Unfortunately, Louis XV failed to overcome these fiscal problems, mainly due to his chronic indecision and lack of commitment. At Versailles, the King and the nobility surrounding him showed signs of ennui, signaling a monarchy in steady decline. Worse, Louis seemed to be aware of the forces of anti-monarchism threatening his family's rule and yet failed to do anything to stop them. Popular legend has it that Louis even predicted, "After us will come the deluge (Après nous, le déluge)." A chillingly accurate prediction, and one Louis XV could have done something to prevent.

King Louis expended a great deal of energy in the pursuit of women. His marriage to Marie Leszczynska produced many children (see below), but the King was persistently (and notoriously) unfaithful. Some of his mistresses, such as Madame de Pompadour and the former prostitute Madame du Barry, are as well-known as the King himself, and his affairs with all five Mailly-Nesle sisters are documented by the formal agreements into which he entered. In his later years, Louis developed a penchant for young girls, keeping several at a time in a house known as the Parc aux Cerfs ("Deer Park").

At first he was known popularly as Louis XV, Le Bien-aimé (the well-beloved) after a near-death illness in Metz in 1744 when the entire country prayed for his recovery. However, his weak and ineffective rule was a contributing factor to the general decline that culminated in the French Revolution. Popular faith in the monarchy was shaken by the scandals of Louis' private life, and by the end of his life he had become the well-hated. On January 5, 1757, would-be assassin Robert Damiens entered Versailles and stabbed him in the side with a penknife.

Louis15-1.jpg

In 1743, France entered the War of the Austrian Succession. During Louis' reign Corsica and Lorraine were won, but a few years later the huge colonial empire was lost, a result of the Seven Years' War with Great Britain. The Treaty of Paris (1763), which ended the Seven Years' War, was one of the most humiliating episodes of the French monarchy. France abandoned India, Canada, and the west bank of the Mississippi River. Although France still held New Orleans, lands west of the Mississippi, and Guadeloupe, it was this defeat and the signing of the treaty that marked the first stage of a total abandonment of the New World. France's foreign policies were a dismal failure. Its prestige sank dramatically.

King Louis XV died of smallpox at the Palace of Versailles. He was the first Bourbon whose heart was not, as tradition demanded, cut out and placed in a special coffer. Instead, alcohol was poured into his coffin and his remains were soaked in quicklime. In a surreptitious late-night ceremony attended by only one courtier, the body was taken to the cemetery at Saint Denis Basilica.

Because Louis XV's son, Louis, Dauphin de France, had died nine years earlier, Louis's grandson ascended to the throne as King Louis XVI.

The King's mismanagement of the financial situation and his scandalous private life undermined the entire French monarchy, and the problems of Louis XV's reign would haunt (and eventually destroy) the lives of his successors - Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette.

Two of Louis's other grandchildren also became Kings of France - Louis XVIII and Charles X.

Marriage and Children

- On September 4, 1725 he married Marie Leszczynska, Princess of Poland (1703-1768). They had ten children:

- Louise-Elisabeth (August 14, 1727 - December 6, 1759)

- Henriette-Anne (August 14, 1727 - February 10, 1752)

- Marie-Louise (July 28, 1728 - February 19, 1733)

- Louis, Dauphin de France (September 4, 1729 - December 20, 1765)

- Philippe (August 30, 1730 - April 17, 1733)

- Adélaïde (March 23, 1732 - February 27, 1800)

- Victoire-Louise (May 11, 1733 - June 7, 1799)

- Sophie-Philippine (July 17, 1734 - March 3, 1782)

- Thérèse-Félicité (May 16, 1736 - September 28, 1744)

- Louise-Marie (July 5, 1737 - December 23, 1787)

See also