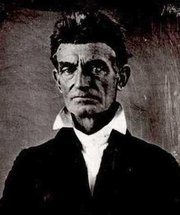

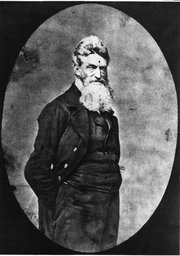

John Brown (abolitionist)

|

|

John Brown (May 9, 1800 – December 2, 1859) was an American abolitionist who played a major part in the history of slavery in the United States leading up to the American Civil War. Brown took part in the violence during the Bleeding Kansas crisis, but his most famous action was his leadership of the raid on the federal armory at Harpers Ferry, Virginia (in modern-day West Virginia). The killings that followed, Brown's subsequent capture by Robert E. Lee, his trial, and execution by hanging are generally considered an important part of the origins of the Civil War.

Brown's nicknames were Oswatomie Brown, Old Man Brown, Captain Brown and Old Brown of Kansas. His aliases were "Nelson Hawkins," "Shabel Morgan," and "Isaac Smith." Later the song "John Brown's Body" became a Union marching song during the Civil War.

| Contents |

Early years

Brown was born in Torrington, Connecticut. He was the second son of Owen Brown and Ruth Mills Brown. His father was a tanner and strict Calvinist who hated slavery and taught his trade to his son. In 1805, the family moved to Hudson, Ohio, where Owen Brown opened a tannery.

At the age of 16, John Brown moved, left his family, and went to Plainfield, Massachusetts, where he enrolled in school. Shortly afterward, he transferred to an academy in Litchfield, Connecticut. He hoped to become a Congregationalist minister, but money ran out and he suffered from eye inflammations, which forced him to give up the academy and return to Ohio. In Hudson, he worked briefly at his father's tannery before opening a successful tannery of his own outside town with his adopted brother.

On June 21, 1820, Brown married Dianthe Lusk. Their first child, John Jr., was born 13 months later. In 1825, Brown and his family moved to Randolph, Pennsylvania, where he purchased 200 acres (800,000 m²). He cleared an eighth of it, built a cabin, a barn and a tannery. Within a year the tannery employed 15 men. Brown also made money raising cattle and surveying. He helped to establish a post office and a school.

Adverse times

In 1831, one of his sons died. Brown fell ill, and his businesses began to suffer, which left him into terrible debt. In the summer of 1832, shortly after the death of a new born son, his wife Dianthe died. On June 14, 1833, Brown married 16-year-old Mary Ann Day (April 15, 1817—May 1, 1884), originally of Meadville, Pennsylvania. They eventually had 13 children, in addition to the five children from his previous marriage.

In 1836, Brown moved his family to Franklin Mills in Ohio (now part of Kent). There he borrowed money to buy land in the area. He suffered great financial losses in the economic Panic of 1837 and was even jailed once. He attempted everything to get out of debt, including tanning, cattle trading, horse breeding and sheep tending. He was declared bankrupt by a federal court on September 28, 1842. In 1843, four of his children died of dysentery.

One year later, Brown partnered with Simon Perkins of Akron to enter the wool business. Two years later, the partners opened an office in Springfield, Massachusetts, where Brown moved to become manager. His family remained in Ohio, and the Springfield office suffered financially. Brown then convinced Perkins to send him to England to sell their wool.

Before departing, Brown moved his family from Akron to North Elba, New York, and settled on lands set aside by Gerrit Smith, a wealthy abolitionist who had donated 120,000 acres (486 km²) of his property in the Adirondack Mountains to African American families willing to clear and farm the land. Brown lasted only two months in England, and he lost about $40,000 on the venture. While in North Elba, Brown taught his neighbors how to farm the rocky soil. Perkins and Brown closed the Springfield office in 1850, and Brown returned with his family to Ohio a year later. In Ohio, Brown developed the ague, his son Frederick fell into a serious mental illness, and his youngest son died of the whooping cough. In 1854, Brown and Perkins dissolved their relationship.

Active role as an abolitionist

Brown moved his family back to North Elba in June 1855, but he considered leaving his family there and following his oldest sons John Jr., Owen, Salmon and Frederick to Kansas. Their motives were to start a new life in farming and to join the free-state settlers in the contentious, developing territory. The Kansas-Nebraska Act provided that the people of the Kansas territory would vote on the question of slavery there. Sympathizers from both sides of the question packed the territory with settlers (often using unscrupulous methods, such as bribery and coercion).

The sons asked their father to join them in Kansas. Brown was torn between settling in North Elba with his wife and moving to Kansas with his older sons. Through his deliberations, he consulted through correspondence with Gerrit Smith and Frederick Douglass. Brown had first met Douglass in Springfield, Massachusetts in 1847. Douglass wrote about Brown, "Though a white gentleman, he is in sympathy a black man, and as deeply interested in our cause, as though his own soul had been pierced with the iron of slavery." At their first meeting Brown outlined to Douglass his plan to lead a war to free slaves, including the establishment of a "Subterranean Pass Way" in the Allegheny Mountains. Douglass often referred to him as Captain Brown.

Brown eventually decided to move to Kansas. He took with him guns and ammunition, which he had collected from sympathetic free-state committees.

Actions in Kansas

Brown was particularly affected by the Sacking of Lawrence, in which a sheriff-led posse destroyed newspaper offices, a hotel, and killed two men. In the evening of May 24, 1856, Brown, his four sons, a son-in-law, and two other men, killed with broadswords five settlers who were presumed to be proslavery on Pottawatomie Creek. Brown later said that he had not participated in the killings during the Pottawatomie Massacre, but that he did approve of them. He went into hiding after the killings, and two of his sons, John Jr. and Jason, were arrested. During their confinement, they were mistreated, which left John Jr. mentally scarred.

On June 2, Brown led a successful attack on a band of Missourians led by Captain Henry Pate. Pate and his men had entered Kansas to capture Brown and others.

John Brown's struggle with proslavery forces in Kansas brought him national attention, and he became a hero to many Northern abolitionists. With only two dozen men he successfully defended the free-soil town of Osawatomie (on August 30) against an attack of about 400 men. The success earned him the nickname "Osawatomie Brown." A play titled Osawatomie Brown soon appeared on Broadway telling his story.

That autumn, Brown went into hiding and engaged in guerrilla activities.

Putting his Virginia plan together

By November 1856, Brown had returned to the East to solicit more funds. He spent the next two years travelling New England raising funds. Amos Adams Lawrence, a prominent Boston merchant, contributed a large amount of capital. Franklin Sanborn, secretary for the Massachusetts State Kansas Committee, introduced Brown to several influential abolitionists in the Boston area in January of 1857. They included William Lloyd Garrison, Thomas Wentworth Higginson, Theodore Parker and George Luther Stearns. This group was later called the Secret Six and the Committee of Six. It remains unclear how much of Brown's scheme the Secret Six were aware of.

On January 7, 1858, the Massacusetts Committee pledged to Brown 200 Sharp's rifles and ammunition, which was being stored at Tabor, Iowa.

In the following months, Brown continued to raise funds, visiting Worcester, Springfield, New Haven, Syracuse and Boston. In Boston he met Henry David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson. He received many pledges but little cash. In March, while in New York City, he was introduced to High Forbes. Forbes, an English mercenary, had experience as a military tactician gained while fighting with Giuseppe Garibaldi in Italy in 1848. Brown hired him to be the drillmaster for his men and to write their tactical handbook. They agreed to meet in Tabor that summer.

In March, Brown contracted Charles Blair of Collinsville, Connecticut for 1,000 pikes.

Using the alias Nelson Hawkins, Brown traveled through the Northeast and then went to visit his family in Hudson, Ohio. On August 7, he arrived in Tabor. Forbes arrived two days later. Over a number of weeks, the two men put together a "Well-Matured Plan" for fighting slavery in the South. The men quarreled over many of the details. In November, their troops left for Kansas. Forbes had not received his salary and was still feuding with Brown, so he returned to the East instead of venturing into Kansas. He would soon threaten to expose the plot to the government.

Because the October elections saw a free-state victory, Kansas was quiet. Brown made his men return to Iowa, where he fed them tidbits of his Virginia scheme. In January 1858, Brown left his men in Springdale, Iowa, and set off to visit Frederick Douglass in Rochester, New York. There he discussed his plans with Douglass, and reconsidered Forbes' criticisms. Brown wrote a Provisional Constitution that would create a government for a new state in the region of his invasion. Brown then traveled to Peterboro, New York and Boston to discuss matters with the Secret Six. In letters to them he indicated that, along with recruits, he would go into the South equipped with weapons to do "Kansas work."

Brown and twelve of his followers, including his son Owen, traveled to Chatham, Ontario where he convened on April 27 a Constitutional Convention. The convention was put together with the help of Dr. Martin Delany. One-third of Chatham's 6,000 residents were fugitive slaves. The convention assembled 34 blacks and 12 whites to adopt Brown's Provisional Constitution. During the convention, Brown illuminated his plans to make Kansas rather than Canada the end of the Underground Railroad. This would be the Subterranean Pass Way. He never mentioned or hinted at the idea of Harpers Ferry.

Although nearly all of the delegates signed the Constitution, very few volunteered to join Brown's forces. Brown was elected commander-in-chief and he named John Henrie Kagi as Secretary of War. Richard Realf was named Secretary of State. Elder Monroe, a black minister, was to act as president until another was chosen. A.M. Chapman was the acting vice president; Delany, the corresponding secretary. Either during this time or shortly after, the Declaration of the Slave Population of the U.S.A. was written.

At this time, Forbes began to expose the plans to Massachusetts Senator Henry Wilson and others. The Secret Six feared their names would be made public. Howe and Higginson wanted no delays in Brown's progress, while Parker, Stearns, Smith and Sanborn insisted on postponement. Stearn and Smith were the major sources of funds, and their words carried more weight.

To throw Forbes off the trail and to invalidate his assertions Brown returned to Kansas in June, and he remained in that vicinity for six months. There he joined forces with James Montgomery, who was leading raids into Missouri. On December 20, Brown led his own raid, in which he liberated eleven slaves, took captive two white men, and stole horses and wagons. On January 20, 1859, he embarked on a lengthy journey to take the eleven liberated slaves to Detroit, Michigan and then on a ferry to Canada.

Over the course of the next few months he traveled again through Ohio, New York, Connecticut and Massachusetts to draw up more support for the cause. On May 9, he delivered a lecture in Concord, Massachusetts. In attendance were Bronson Alcott, Rockwell Hoar, Emerson and Thoreau. Brown also reconnoitered with the Secret Six. In June he paid his last visit to his family in North Elba, before he departed for Harpers Ferry.

Raid on Harpers Ferry

Brown arrived in Harpers Ferry on June 3, 1859. A few days later, under the name Isaac Smith, he rented a farmhouse nearby in Maryland. He awaited the arrival of his recruits. They never materialized in the numbers he expected. In late August he met with Douglass in Chambersburg, Pennsylvania, where he revealed the Harpers Ferry plan. Douglass expressed severe reservations, rebuking Brown's pleas to join the mission.

In late September, the 950 pikes arrived from Charles Blair. Kagi's draft plan called for a brigade of 4,500 men, but Brown had only 21 (16 white and 5 black). They ranged in age from 21 to 49. Twelve of them had been with Brown in Kansas raids.

On October 16, 1859, Brown (leaving three men behind as a rear guard) led 18 men in an attack on the armory at Harpers Ferry. He had received 200 breechloading .52 caliber Sharps carbines and pikes from northern abolitionist societies in preparation for the raid. The armory was a large complex of buildings that contained 100,000 muskets and rifles, which Brown planned to seize and use to arm local slaves. They would then head south, and a general revolution would begin.

Initially, the raid went well. They met no resistance entering the town. They cut the telegraph wires and easily captured the armory, which was being defended by a single watchman. They next rounded up hostages from nearby farms, including Colonel Lewis Washington, great-grand-nephew of George Washington. They also spread the news to the local slaves that their liberation was at hand. Things started to go wrong when an eastbound Baltimore & Ohio train approached the town. The train's baggage master tried to warn the passengers. Brown's men yelled for him to halt and then opened fire. The baggage master, Hayward Shepherd, became the first casualty of John Brown's war against slavery. Ironically, Shepherd was a free black man. For some reason, after shooting Shepherd, Brown allowed the train to continue on its way. News of the raid reached Washington, D.C. by late morning.

In the early morning, they captured and took prisoner John Daingerfield, an armory clerk who had come into work. Daingerfield was taken to the guardhouse, presented to Brown and then imprisoned with the other hostages.

In the meantime, local farmers, shopkeepers, and militiamen pinned down the raiders in the armory by firing from the heights behind the town. Some of the local men were shot by Brown's men. All of the stores and the arsenal were in the hands of Brown's men, making it impossible for the townsmen to get arms or ammunition. At noon, a company of militiamen seized the bridge, blocking the only escape route. The remaining raiders took cover in the engine house, a small brick building near the armory. Brown then moved his prisoners and remaining men into the engine house. He had the doors and windows barred and portholes were cut through the brick walls. The surrounding forces barraged the engine house, and the men inside fired back with occasional fury. The exchanges lasted throughout the day.

By morning (October 18) the building was surrounded by a company of U.S. Marines under the command of Lt. Col. Robert E. Lee. A young lieutenant, J.E.B. Stuart, approached under a white flag and told the raiders that their lives would be spared if they surrendered. Brown refused and the Marines stormed the building. Stuart served as a messanger between Lee and Brown. Throughout the negotiations, Brown refused to surrender. Brown's final chance came when Stuart approached and asked "Are you ready to surrender, and trust to the mercy of the government?" Brown replied, "No, I prefer to die here." Stuart then gave a signal. The Marines used sledge hammers and a make-shift battering-ram to break down the engine room door. Amid the chaos, Lieutenant Green cornered Brown and gave him a thrust with his sword that was powerful enough to raise Brown completely off the ground. Brown's life was spared because Green's sword struck Brown's belt. Brown fell forward and Green struck him several times over the head, wounding his scalp.

One Marine was killed. Ten of Brown's men were killed (including his sons Watson and Oliver). Five of Brown's men escaped (including his son Owen), and six were captured along with Brown.

Brown and the others captured were held in the office of the armory. On October 18, Virginia Governor Henry A. Wise, Virginia Senator James M. Mason, and Representative Clement Vallandingham of Ohio arrived in Harpers Ferry. Mason led the three-hour questioning session of Brown.

Although the attack had taken place on Federal property, Wise ordered that Brown and his men would be tried in Virginia. The trial began October 27, after a doctor pronounced Brown fit for trial. Brown was charged with murdering four whites and a black, with conspiring with slaves to rebel, and with treason against Virginia. A series of lawyers were assigned to Brown, including George Hoyt. Hiram Griswold concluded the defense on October 31. He argued that Brown could not be guilty of treason against a State to which he owed no loyalty, that Brown had not killed anyone himself, and that the failure of the raid indicated that Brown had not conspired with slaves. Andrew Hunter presented the closing arguments for the prosecution.

On November 2, after a week-long trial and 45 minutes of deliberation, the Charles Town jury found Brown guilty on all three counts. Brown was sentenced to be hanged in public on December 2. In response to the sentence, Ralph Waldo Emerson remarked that "[John Brown] will make the gallows as holy as the crucifix."

During his month in jail, he was allowed to receive and send letters. Brown refused to be rescued by Silas Soule, a friend from Kansas, who had somehow broken into the prison. Brown said that he was ready to die as a martyr, and Silas left him to be executed. On December 1, his wife joined him for his last meal. She was denied permission to stay for the night, prompting Brown to lose his composure for the only time through the ordeal.

On the morning of December 2, Brown read his Bible and wrote a final letter to his wife, which included his will. At 11:00 he was escorted through a crowd of 2,000 spectators and soldiers. He was accompanied by the sheriff and his assistants, but no minister. Brown elected to receive no religious services in the jail or at the scaffold. He was hanged at 11:15 and pronounced dead at 11:50.

On the day of his death he wrote "I, John Brown, am now quite certain that the crimes of this guilty land will never be purged away but with blood. I had, as I now think, vainly flattered myself that without very much bloodshed it might be done."

John Brown is buried on the John Brown Farm in North Elba, New York, south of Lake Placid.

Senate investigation

On December 14, 1859, the U.S. Senate appointed a bipartisan committee to discover the facts of the Harpers Ferry attack and to determine whether any citizens contributed arms, ammunition or money. The Democrats attempted to implicate the Republicans in the raid; the Republicans tried to disassociate themselves with Brown and his acts.

The Senate committee heard testimony from 32 witnesses. The report, authored by chairman James M. Mason, was published in June 1860. It found no direct evidence of a conspiracy, but implied that the raid was a result of Republican doctrines. The two committee Republicans published a minority report.

Aftermath of the raid

The raid on Harpers Ferry is generally thought to have done much to set the nation on a course toward civil war. Southern slaveowners, fearful that other abolitionists would emulate Brown and attempt to lead slave rebellions, began to organize militias to defend their property (being both their land and their slaves). These militias, well established by 1861, were in effect a ready-made Confederate army, making the South more prepared for secession than it otherwise might have been.

In light of the upcoming elections in November 1860, the Republican political and editorial response to John Brown was that he was insane. Democrats charged that Brown's raid was an inevitable consequence of Abolitionism.

After the Civil War, Douglass wrote, "Did John Brown fail? John Brown began the war that ended American slavery and made this a free Republic. His zeal in the cause of my race was far greater than mine. I could live for the slave, but he could die for him."

See also

Further reading

- The Life and Letters of John Brown, edited by Franklin Sanborn (1891)

- John Brown and his Men, by Richard Hinton (1894)

- John Brown 1800-1859: A Biography Fifty Years After, by Oswald Garrison Villard (1910)

- John Brown, by W.E.B. Du Bois (ISBN 0679783539)

- The Burden of Southern History, by C. Vann Woodward (1960)

- To Purge This Land With Blood: A Biography of John Brown, by Stephen B. Oates (1970) (ISBN 0870234587)

- John Brown: The Legend Revisited by Merrill D. Peterson (2002) (ISBN 0813921325)

- John Brown, Abolitionist : The Man Who Killed Slavery, Sparked the Civil War, and Seeded Civil Rights, by David S. Reynolds (2005) (ISBN 0375411887)

External links

- Debs, Eugene. John Brown: History’s Greatest Hero (http://www.marxists.org/archive/debs/works/1907/johnbrown.htm). Originally published in Appeal to Reason, November 23, 1907. Retrieved May 16, 2005.

- Johnson, Andrew. What John Brown Did in Kansas (http://www.adena.com/adena/usa/cw/cw234.htm), a speech to the United States House of Representatives, December 12 1859. Originally published in The Congressional Globe, The Official Proceedings of Congress, Published by John C. Rives, Washington, D. C. Thirty-Sixth Congress, 1st Session, New Series...No. 7, Tuesday, December 13, 1859, pages 105-106. Retrieved May 16, 2005.de:John Brown

it:John Brown (abolizionista) pl:John Brown sk:John Brown (abolicionista) zh-cn:约翰·布朗