United States Senate

|

|

Us_senate_seal.png

The United States Senate is one of the two houses of the Congress of the United States, the other being the House of Representatives. In the Senate, each state is equally represented by two members, regardless of population; as a result, the total membership of the body is 100. Senators serve for six-year terms, which are staggered so that elections are held in approximately one-third of the seats (a "class") every second year. The Vice President of the United States is the presiding officer of the Senate but is not a senator and does not vote except to break ties. The Senate is regarded as a more deliberative body than the House of Representatives; the Senate is smaller and its members serve longer terms, allowing for a more collegiate and less partisan atmosphere that is somewhat more insulated from public opinion than the House. The Senate has several exclusive powers enumerated in the Constitution not granted to the House; most significantly, the President must ratify treaties and make important appointments "with the Advice and Consent of the Senate" (Article I).

A bicameral Congress was created as a result of the Connecticut Compromise, a compromise made at the Constitutional Convention, under which states would be represented on the basis of population in the House of Representatives, but would be equally represented in the Senate. The Constitution provides that the approval of both houses is necessary for the passage of legislation. The exclusive powers enumerated to the Senate in the Constitution are regarded as more important than those exclusively enumerated to the House. As a result, the responsibilities of the Senate (the "upper house") are more extensive than those of the House of Representatives (the "lower house").

The Senate of the United States was named after the ancient Roman Senate. The chamber of the United States Senate is located in the north wing of the Capitol building, in Washington, D.C., the national capital. The House of Representatives convenes in the south wing of the same building.

| Contents |

History

Main article: History of the United States Senate

Under the Articles of Confederation, Congress was a unicameral body in which each state was equally represented. The inefficacy of the federal government under the Articles led Congress to summon a Constitutional Convention in 1787; all states except Rhode Island agreed to send delegates. Many delegates called for a second Congressional chamber, modeled on the House of Lords (the aristocratic upper house of the British Parliament). For example, John Dickinson argued that the second chamber should "consist of the most distinguished characters, distinguished for their rank in life and their weight of property, and bearing as strong a likeness to the British House of Lords as possible."

The structure of Congress was one of the most divisive issues facing the Convention. The Virginia Plan called for a bicameral Congress; the lower house would be elected directly by the people, and the upper house would be elected by the lower house. The Virginia Plan was primarily supported by the larger states, as it called for representation based on population in both Houses. The smaller states, however, favored the New Jersey Plan, which called for a unicameral Congress with equal representation for the states. Eventually, a compromise, known as the Connecticut Compromise or the Great Compromise, was reached; one house of Congress (the House of Representatives) would provide proportional representation, whereas the other (the Senate) would provide equal representation. In order to further preserve the authority of the states, it was provided that state legislatures, rather than the people, would elect senators. The Constitution was ratified by the requisite number of states (nine out of the 13) in 1788, but its full implementation was set for March 4, 1789. However, the Senate could not begin work until a majority of the members assembled on April 6 of the same year. The Founding Founders intended the Senate to be a more stable, deliberative body than the House of Representatives. James Madison described the Senate's purpose as "A necessary fence against...fickleness and passion". George Washington, in answer to a question by Thomas Jefferson, said "we pour legislation into the senatorial saucer to cool it (from the The House of Representatives)".

The early 19th century was marked by the service of distinguished orators and statesmen such as Daniel Webster, John C. Calhoun, Henry Clay, Stephen Douglas and Thomas Hart Benton. The era, however, was also marred by sectional clashes between the free North and the slaveholding South. For most of the first half of the 19th century, a balance between North and South existed in the Senate, as the numbers of free and slave states were equal. Southern senators could often block schemes passed by the House of Representatives, a body dominated by the populous North. Sectional conflict was most pronounced over the issue of slavery, and persisted until the Civil War (1861–1865). The war, which began soon after several southern states declared secession from the Union, culminated in the South's defeat and in the abolition of slavery. The ensuing years of Reconstruction witnessed large majorities for the Republican Party, which many Americans associated with the Union's victory in the Civil War. The efforts of "Radical Republicans" led to the impeachment of Democratic President Andrew Johnson in 1868 for political purposes; the trial ultimately ended in acquittal, with the Senate falling one vote short of the two-thirds majority requisite for conviction.

Reconstruction ended in 1877, at approximately the same time as the Gilded Age began. This period was marked by sharp political divisions in the electorate; both the Democrats and the Republicans were in power in the Senate, but neither could obtain large majorities. At the same time the Senate descended into a period of irrelevance that stood in sharp contrast with the pre-Civil War era. Very few senators had long and distinguished careers, with most serving but for a single term. The corruption of state legislatures was also widespread; nine cases of bribery in Senate elections arose between 1866 and 1906. Many individuals, furthermore, perceived the Senate as a bastion of the rich and the �lite. Several reformers of the Progressive Era pushed for the direct election of senators by the people, rather than state legislatures; they achieved their objective in 1913 with the ratification of the Seventeenth Amendment. The Amendment ultimately had the result of making senators more responsive to the concerns of voters.

In the 1910s a Senate leadership structure developed, with Henry Cabot Lodge and John Worth Kern becoming the unofficial leaders of the Republican and Democratic parties, respectively. The Democrats appointed their first official leader, Oscar Underwood, in 1925; the Republicans followed with Charles Curtis in 1925. Initially, the powers of the leaders were very limited, and individual senators—especially the chairmen of important committees—still held more clout. The influence of the party leaders, however, would eventually grow, especially during the tenures of skilled leaders such as Lyndon B. Johnson.

Members and elections

Article One of the Constitution stipulates that each state may elect two senators. The Constitution further stipulates that no constitutional amendment may deprive a state of its equal suffrage in the Senate without the consent of the state concerned. The District of Columbia and territories are not entitled to any representation. As there are presently 50 states, the Senate comprises 100 members. The senator from each state with the longer tenure is known as the "senior senator," and his or her counterpart as the "junior senator"; this convention, however, does not have any special significance.

Senators serve for terms of six years each; the terms are staggered so that approximately one-third of the Senate seats are up for election every two years. The staggering of the terms is arranged such that both seats from a given state are never contested in the same general election. Senate elections are held on the first Tuesday after the first Monday in November, Election Day, and coincide with elections for the House of Representatives. Each senator is elected by his or her state as a whole. Generally, the Republican and Democratic parties choose their candidates in primary elections, which are typically held several months before the general elections. Ballot access rules for independent and third party candidates vary from state to state. For the general election, almost all states use the first-past-the-post system, under which the candidate with a plurality of votes (not necessarily an absolute majority) wins. The sole exception is Louisiana, which uses runoff voting.

Once elected, a senator continues to serve until the expiry of his or her term, death, or resignation. Furthermore, the Constitution permits the Senate to expel any member with a two-thirds majority. Fifteen members have been expelled in the history of the Senate; 14 of them were removed in 1861 and 1862 for supporting the Confederate secession, which led to the American Civil War. No senator has been expelled since; however, many have chosen to resign when faced with expulsion proceedings (most recently, Bob Packwood in 1995). The Senate has also passed several resolutions censuring members; censure requires only a simple majority and does not remove a senator from office.

The Seventeenth Amendment provides that vacancies in the Senate, however they arise, may be filled by special elections. A special election for a Senate seat need not be held immediately after the vacancy arises; instead, it is typically conducted at the same time as the next biennial congressional election. If a special election for one seat happens to coincide with a general election for the state's other seat, then the two elections are not combined, but are instead contested separately. A senator elected in a special election serves until the original six-year term expires, and not for a full term of his or her own.

Furthermore, the Seventeenth Amendment provides that any state legislature may empower the Governor to temporarily fill vacancies. The interim appointee remains in office until the special election can be held. All states, with the sole exception of Arizona, have passed laws authorizing the Governor to make temporary appointments. Senators are entitled to prefix "The Honorable" to their names. The annual salary of each senator, as of 2005, is $162,100; the President pro tempore and party leaders receive larger amounts. Analysis of financial disclosure forms by CNN in June 2003 revealed that at least 40 of the then senators were millionaires. In general, senators are regarded as more important political figures than members of the House of Representatives because there are fewer of them, and because they serve for longer terms, represent larger constituencies (except for House at-large districts, which comprise entire states), sit on more committees, and have more staffers. The prestige commonly associated with the Senate is reflected by the background of presidents and presidential candidates; far more sitting senators have been nominees for the presidency than sitting representatives.

Qualifications

Article I, Section 3 of the Constitution sets forth three qualifications for senators: each senator must be at least thirty years old, must have been a citizen of the United States for at least the past nine years, and must be (at the time of the election) an inhabitant of the state he or she represents. The age and citizenship qualifications for senators are more stringent than those for representatives. In Federalist No. 62, James Madison justified this arrangement by arguing that the "senatorial trust" called for a "greater extent of information and stability of character."

Furthermore, under the Fourteenth Amendment, any federal or state officer who takes the requisite oath to support the Constitution, but later engages in rebellion or aids the enemies of the United States, is disqualified from becoming a senator. This provision, which came into force soon after the end of the Civil War, was intended to prevent those who sided with the Confederacy from serving. The Amendment, however, provides that a disqualified individual may still serve if two-thirds of both Houses of Congress vote to remove the disability.

Under the Constitution, the Senate (not the courts) is empowered to judge if an individual is qualified to serve. During its early years, however, the Senate did not closely scrutinize the qualifications of members. As a result, three individuals that were Constitutionally disqualified due to age were admitted to the Senate: twenty-nine-year-old Henry Clay (1806), and twenty-eight-year-olds Armistead Mason (1816) and John Eaton (1818). Such an occurrence, however, has not been repeated since. In 1934, Rush Holt was elected to the Senate at the age of twenty-nine; he waited until he turned thirty to take the oath of office.

Officers

The party with a majority of seats is known as the majority party; if two or more parties in opposition are tied, the Vice President's affiliation determines which is the majority party. Each party elects a senator to serve as floor leader, a position which entails acting as the party's chief spokesperson. The Majority Leader is, furthermore, responsible for controlling the agenda of the Senate; for example, he or she schedules debates and votes. Each party, furthermore, elects a whip to assist the leader. A whip works to ensure that his or her party's senators vote as the party leadership desires.

The Constitution provides that the Vice President of the United States serves as the President of the Senate and holds a casting vote. By convention, the Vice President presides over very few Senate debates, attending only on important ceremonial occasions (such as the swearing-in of new senators) or at times when his or her casting vote may be crucial. The Constitution also authorizes the Senate to elect a president pro tempore (Latin for "temporary president") to preside in the Vice President's absence; the most senior senator of the majority party is customarily chosen to serve in this position. Like the Vice President, the president pro tempore does not normally preside over the Senate. Instead, he or she typically delegates the responsibility of presiding to junior senators of the majority party. Frequently, freshmen senators (newly-elected members) are allowed to preside so that they may become accustomed to the rules and procedures of the body.

The presiding officer sits in a chair in the front of the Senate chamber. The powers of the presiding officer are extremely limited; he or she primarily acts as the Senate's mouthpiece, performing duties such as announcing the results of votes. The Senate's presiding officer controls debates by calling on members to speak; the rules of the Senate, however, compel him or her to recognize the first senator who rises. The presiding officer may rule on any "point of order" (a senator's objection that a rule has been breached), but the decision is subject to appeal to the whole house. Thus, the powers of the presiding officer of the senate are far less extensive than those of the Speaker of the House.

The Senate is also served by several officials who are not members. The Senate's chief administrative officer is the Secretary of the Senate, who maintains public records, disburses salaries, monitors the acquisition of stationery and supplies, and oversees clerks. The Secretary is aided in his or her work by the Assistant Secretary of the Senate. Another official is the Sergeant-at-Arms, who, as the Senate's chief law enforcement officer, maintains order and security on the Senate premises. The Sergeant-at-Arms position has evolved; now the Capitol Police handle routine police work, while the Sergeant-at-Arms main deals with administrative oversight of technological services.

Procedure

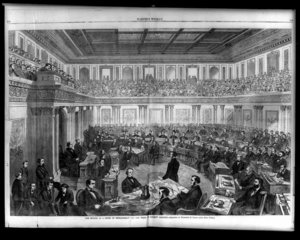

Like the House of Representatives, the Senate meets in the United States Capitol in Washington, D.C. At one end of the Chamber of the Senate is a dais from which the president pro tempore presides. The lower tier of the dais is used by clerks and other officials. One hundred desks are arranged in the Chamber in a semicircular pattern; the desks are divided by a wide central aisle. By tradition, Democrats sit on the right of the center aisle, while Republicans sit on the left, as viewed from the presiding officer's chair. Each senator chooses a desk on the basis of seniority within his or her party; by custom, the leader of each party sits in the front row. Sittings are normally held on weekdays; meetings on Saturdays and Sundays are rare. Sittings of the Senate are generally open to the public and are broadcast live on television by C-SPAN 2.

Senate procedure depends not only on the rules, but also on a variety of customs and traditions. In many cases, the Senate waives some of its stricter rules by unanimous consent. Unanimous consent agreements are typically negotiated beforehand by party leaders. Any senator may block such an agreement, but, in practice, objections are rare. The presiding officer enforces the rules of the Senate, and may warn members who deviate from them. The presiding officer often uses the gavel of the Senate to maintain order.

The Constitution provides that a majority the Senate constitutes a quorum to do business. Under the rules and customs of the Senate, a quorum is always assumed to be present unless a quorum call explicitly demonstrates otherwise. Any senator may request a quorum call by "suggesting the absence of a quorum"; a clerk then calls the roll of the Senate and notes which members are present. In practice, senators almost always request quorum calls not to establish the presence of a quorum, but to temporarily delay proceedings. Such a delay may serve one of many purposes; often, it allows Senate leaders to negotiate compromises off the floor. Once the need for a delay has ended, any senator may request the presiding officer to rescind the quorum call.

During debates, senators may only speak if called upon by the presiding officer. The presiding officer is, however, required to recognize the first senator who rises to speak. Thus, the presiding officer has little control over the course of debate. Customarily, the Majority Leader and Minority Leader are accorded priority during debates, even if another senator rises first. All speeches must be addressed to the presiding officer, using the words "Mr. President" or "Madam President." Only the presiding officer may be directly addressed in speeches; other Members must be referred to in the third person. In most cases, senators do not refer to each other by name, but by state, using forms such as "the senior senator from Virginia" or "the junior senator from California."

There are very few restrictions on the content of speeches; there is no requirement that speeches be germane to the matter before the Senate.

The rules of the Senate provide that no senator may make more than two speeches on a motion or bill on the same legislative day. (A legislative day begins when the Senate convenes and ends with adjournment; hence, it does not necessarily coincide with the calendar day.) The length of these speeches is not limited by the rules; thus, in most cases, senators may speak for as long as they please. Often, the Senate adopts unanimous consent agreements imposing time limits. In other cases (for example, for the Budget process), limits are imposed by statute. In general, however, the right to unlimited debate is preserved.

The filibuster is a tactic used to defeat bills and motions by prolonging debate indefinitely. A filibuster may entail long speeches, dilatory motions, and an extensive series of proposed amendments. The longest filibuster speech in the history of the Senate was delivered by Strom Thurmond, who spoke for over twenty-four hours in an unsuccessful attempt to block the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1957. The Senate may end a filibuster by invoking cloture. In most cases, cloture requires the support of three-fifths of the Senate; however, if the matter before the Senate involves changing the rules of the body, a two-thirds majority is required. Cloture is invoked very rarely, particularly because bipartisan support is usually necessary to obtain the required supermajority. If the Senate does invoke cloture, debate does not end immediately; instead, further debate is limited to one hundred hours.

When debate concludes, the motion in question is put to a vote. In many cases, the Senate votes by voice vote; the presiding officer puts the question, and Members respond either "Aye" (in favor of the motion) or "No" (against the motion). The presiding officer then announces the result of the voice vote. Any senator, however, may challenge the presiding officer's assessment and request a recorded vote. The request may be granted only if it is seconded by one-fifth of the senators present. In practice, however, senators second requests for recorded votes as a matter of courtesy. When a recorded vote is held, the clerk calls the roll of the Senate in alphabetical order; each senator responds when his or her name is called. Senators who miss the roll call may still cast a vote as long as the recorded vote remains open. The vote is closed at the discretion of the presiding officer, but must remain open for a minimum of 15 minutes. If the vote is tied, the Vice President, if present, is entitled to a casting vote. If the Vice President is not present, however, the motion is resolved in the negative.

Committees

Dirksen226.jpg

The Senate uses committees (as well as their subcommittees) for a variety of purposes, including the review of bills and the oversight of the executive branch. The appointment of committee members is formally made by the whole Senate, but the choice of members is actually made by the political parties. Generally, each party honors the preferences of individual senators, giving priority on the basis of seniority. Each party is allocated seats on committees in proportion to its overall strength.

Most committee work is performed by sixteen standing committees, each of which has jurisdiction over a specific field such as Finance or Foreign Relations. Each standing committee considers, amends, and reports bills that fall under its jurisdiction. Furthermore, each standing committee considers presidential nominations to offices related to its jurisdiction. (For instance, the Judiciary Committee considers nominees for judgeships, and the Foreign Relations Committee considers nominees for positions in the Department of State.) Committees have extensive powers with regard to bills and nominees; they may block either from reaching the floor of the Senate. Finally, standing committees also oversee the departments and agencies of the executive branch. In discharging their duties, standing committees have the power to hold hearings and to subpoena witnesses and evidence.

The Senate also has several committees that are not considered standing committees. Such bodies are generally known as select committees or special committees; examples include the Select Committee on Ethics and the Special Committee on Aging. Legislation is referred to some of these committees, though the bulk of legislative work is performed by the standing committees. Committees may be established on an ad hoc basis for specific purposes; for instance, the Senate Watergate Committee was a special committee created to investigate the Watergate scandal. Such temporary committees cease to exist after fulfilling their tasks.

Finally, the Congress includes joint committees, which include members of both the Senate and the House of Representatives. Some joint committees oversee independent government bodies; for instance, the Joint Committee on the Library oversees the Library of Congress. Other joint committees serve to make advisory reports; for example, there exists a Joint Committee on Taxation. Bills and nominees are not referred to joint committees. Hence, the power of joint committees is considerably lower than those of standing committees.

Each Senate committee and subcommittee is led by a chairman (always a member of the majority party). Formerly, committee chairmanship was determined purely by seniority; as a result, several elderly senators continued to serve as chairmen despite severe physical infirmity or even senility. Now, committee chairmen are in theory elected, but in practice, seniority is very rarely bypassed. The chairman's powers are extensive; he or she controls the committee's agenda, and may prevent the committee from approving a bill or presidential nomination. Modern committee chairmen are typically not forceful in exerting their influence, although there have been some exceptions. The second-highest member, the spokesperson on the committee for the minority party, is known in most cases the Ranking Member. In the Select Committee on Intelligence and the Select Committee on Ethics, however, the senior minority member is known as the Vice Chairman.

Legislative functions

Most bills may be introduced in either House of Congress. However, the Constitution provides that "All bills for raising Revenue shall originate in the House of Representatives." As a result, the Senate does not have the power to initiate bills imposing taxes. Furthermore, the House of Representatives holds that the Senate does not have the power to originate appropriation bills, or bills authorizing the expenditure of federal funds. Historically, the Senate has disputed the interpretation advocated by the House. However, whenever the Senate originates an appropriations bill, the House simply refuses to consider it, thereby settling the dispute in practice. The constitutional provision barring the Senate from introducing revenue bills is based on the practice of the British Parliament, in which only the House of Commons may originate such measures.

Although it cannot originate revenue bills, the Senate retains the power to amend or reject them. The approval of both the Senate and the House of Representatives is required for any bill, including a revenue bill, to become law. Both Houses must pass the exact same version of the bill; if there are differences, they may be resolved by a conference committee, which includes members of both bodies. For the stages through which bills pass in the Senate, see Act of Congress.

Checks and balances

The Constitution provides that the President can make certain appointments only with the "advice and consent" of the Senate. Officials whose appointments require the Senate's approval include members of the Cabinet, heads of federal executive agencies, ambassadors, Justices of the Supreme Court, and other federal judges. However, Congress may pass legislation to authorize the appointment of less important officials without the Senate's consent. Typically, a nominee is first subject to a hearing before a Senate committee. Committees may block nominees, but do so relatively infrequently. Thereafter, the nomination is considered by the full Senate. In a majority of the cases, nominees are confirmed; rejections of Cabinet nominees are especially rare (there have been only nine nominees rejected outright in the history of the United States).

The powers of the Senate with respect to nominations are, however, subject to some constraints. For instance, the Constitution provides that the President may make an appointment during a congressional recess without the Senate's advice and consent. The recess appointment remains valid only temporarily; the office becomes vacant again at the end of the next congressional session. Nevertheless, Presidents have frequently used recess appointments to circumvent the possibility that the Senate may reject the nominee. Furthermore, as the Supreme Court held in Myers v. United States, although the Senate's advice and consent is required for the appointment of certain executive branch officials, it is not necessary for their removal.

The Senate also has a role in the process of ratifying treaties. The Constitution provides that the President may only ratify a treaty if two-thirds of the senators vote to grant advice and consent. However, not all international agreements are considered treaties, and therefore do not require the Senate's approval. Congress has passed laws authorizing the President to conclude executive agreements without action by the Senate. Similarly, the President may make congressional-executive agreements with the approval of a simple majority in each House of Congress, rather than a two-thirds majority in the Senate. Neither executive agreements nor congressional-executive agreements are mentioned in the Constitution, leading some to suggest that they unconstitutionally circumvent the treaty-ratification process. However, the validity of such agreements has been upheld by the courts.

The Constitution empowers the House of Representatives to impeach federal officials for "Treason, Bribery, or other high Crimes and Misdemeanors" and empowers the Senate to try such impeachments. If the sitting President of the United States is being tried, the Chief Justice of the United States must preside over the trial. During any impeachment trial, senators are constitutionally required to sit on oath or affirmation. Conviction requires a two-thirds majority of the senators present. A convicted official is automatically removed from office; in addition, the Senate may stipulate that the party be banned from holding office in the future. No further punishment is permitted during the impeachment proceedings; however, the party may face criminal penalties in a normal court of law.

In the history of the United States, the House of Representatives has impeached sixteen officials, of whom seven were convicted. (One resigned before the Senate could complete the trial.) Only two Presidents of the United States have ever been impeached: Andrew Johnson in 1868 and Bill Clinton in 1999. Both trials ended in acquittal; in Johnson's case, the Senate fell one vote short of the two-thirds majority required for conviction.

Under the Twelfth Amendment, the Senate has the power to elect the Vice President if no vice presidential candidate receives a majority of votes in the electoral college. The Twelfth Amendment requires the Senate to choose from the two candidates with the highest numbers of electoral votes. Electoral college deadlocks are very rare; in the history of the United States, the Senate has only had to break a deadlock once, in 1837, when it elected Richard Mentor Johnson. The power to elect the President in the case of an electoral college deadlock belongs to the House of Representatives.

Current composition

- Main article: List of United States Senators

| Affiliation | Members | |

| Republican Party | 55 | |

| Democratic Party | 44 | |

| Independent | 1 | |

| Total | 100 | |

See also

References

- Berman, Daniel M. (1964). In Congress Assembled: The Legislative Process in the National Government. London: The Macmillan Company.

- Byrd, Robert C. (1989–1994). The Senate, 1789-1989: Addresses on the History of the United States. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office.

- Congressional Quarterly's Guide to Congress, 5th ed. (2000). Washington, D.C.: Congressional Quarterly Press.

- Story, Joseph. (1891). Commentaries on the Constitution of the United States. (2 vols). Boston: Brown & Little.

- [1] (http://www.yale.edu/lawweb/avalon/debates/626.htm)

- [2] (http://www.thisnation.com/question/037.html)

External links

- The United States Senate. Official Website. (http://www.senate.gov)

- Biographical Directory of the United States Congress, 1774 to Present. (http://bioguide.congress.gov/biosearch/biosearch.asp)