History of the People's Republic of China (3/4)

|

|

| Contents |

Recovery in the 1990s

After the June 4th Incident, a large number of overseas Chinese students were granted political refuge almost unconditionally by foreign governments. The political instability had extended to Hong Kong as well, resulting in a massive emigration tide before the handover of Hong Kong in 1997. (See History of Hong Kong)

It must be noted that the inflation characteristic of the years leading up to the Tiananmen protests has subsided. Political institutions have stabilized, thanks to the institutionalization of procedures of the Deng years and a generational shift from peasant revolutionaries to well-educated, professional technocrats. Social problems have eased as well, as the People's Republic of China rapidly becomes an increasingly well-off nation.

Following the resurgence of conservatives in the aftermath of June 4, economic reform slowed until given a new impetus by Deng Xiaoping's dramatic visit to southern China in early 1992. Deng's renewed push for a market-oriented economy received official sanction at the 14th Party Congress later in the year as a number of younger, reform-minded leaders began their rise to top positions. Deng and his supporters argued that further reform was necessary to raise China's standard of living.

After the visit, the Communist Party Politburo publicly issued an endorsement of Deng's policies of economic openness. Though not completely eschewing political reform, China has consistently placed overwhelming priority on the opening of its economy.

Although another massive protest is unlikely in the near future, social instability due to economic conflicts has become a greater challenge for the third and fourth generation of leaders.

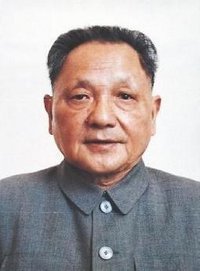

Deng's Legacy

Deng Xiaoping was one of only four peasant revolutionaries to lead China, along with Mao Zedong and the founders of the Han and Ming dynasties.

As mentioned, Deng's policies opened-up the economy to foreign investment and market allocation within a socialist framework. Since his death, under Jiang's tutelage, mainland China has sustained an average of 8% GDP growth annually, achieving one of the world's highest rates of per capita economic growth, if not the highest.

Also as mentioned, due in part to socialist measures and price/currency controls, the inflation characteristic of the years leading up to the Tiananmen protests has subsided. Political institutions have stabilized, thanks to the institutionalization of procedure of the Deng years and a generational shift from peasant revolutionaries to well-educated, professional technocrats. Social problems have eased as well, as the PRC rapidly becomes more of a modern, prosperous nation each year.

According to journalist Jim Rohwer, for example, "the Dengist reforms of 1979-1994 brought about probably the biggest single improvement in human welfare anywhere at any time." This improvement was due to the fact that the reforms affected hundreds of millions of people.

Deng's reforms, however, have left a number of issues unresolved. As a result of his market reforms, it became obvious by the mid-1990s that many state-owned enterprises (owned by the central government, unlike TVEs publicly owned at the local level) were unprofitable and needed to be shut down to prevent their being a permanent and unsustainable drain on the economy. Furthermore, by the mid-1990s most of the benefits of Deng's reforms, particularly in agriculture, had run their course; rural incomes had become stagnant, leaving the PRC's leaders in search of new means to boost economic growth or else risk a massive social explosion.

Finally, the Dengist policy of asserting the primacy of economic development, while maintaining the rule of the Communist Party, has raised questions in the West. Many observers both within China and outside question the degree to which a one-party system can indefinitely maintain control over an increasingly dynamic and prosperous Chinese society. The gravity of these concerns, however, pales in comparison to the social ills faced by China as late as the Tiananmen rebellion of 1989, not to mention the days of mass famine and civil war before the founding of the People's Republic.

Jiang Zemin made a eulogy to the late revolutionary and Long March veteran stating, "The Chinese people love Comrade Deng Xiaoping, thank Comrade Deng Xiaoping, mourn for Comrade Deng Xiaoping, and cherish the memory of Comrade Deng Xiaoping because he devoted his life-long energies to the Chinese people, performed immortal feats for the independence and liberation of the Chinese nation."

Third Generation of Leaders

Jiang Zemin was a compromise candidate chosen by Deng Xiaoping and other party elders to replace the then-party chief Zhao Ziyang, who was considered too conciliatory to student protesters. Although not directly involved with the crackdown, he was elevated to central party positions after the Tiananmen Square protests of 1989 for his role in averting similar protests in Shanghai.

With support from Jiang Zemin and Li Peng, then president and premier respectively, the government enacted tough macroeconomic control measures. Favoring healthy, sustainable development, the PRC expunged low-tech, duplicated projects and sectors that would result in "a bubble economy" and projects in transport, energy, agriculture and sectors, averting violent market fluctuations. Attention has focused on strengthening agriculture, still the economic base of the developing country and on continuing a moderately tight monetary policy.

Deng's health deteriorated in the years prior to his death in 1997. During that time, President Jiang Zemin and other members of his generation gradually assumed control of the day-to-day functions of government. This "third generation" leadership governed collectively with President Jiang at the center.

In March 1998, Jiang was re-elected President during the 9th National People's Congress. Premier Li Peng was constitutionally required to step down from that post. He was elected to the chairmanship of the National People's Congress.

Vice Premier Zhu Rongji was nominated as premier of the State Council of the People's Republic of China by President Jiang Zemin to replace Li and confirmed by the Ninth National People's Congress (NPC) on March 17, 1998 at the NPC First Session. He was reelected Standing Committee member of Political Bureau of 15th CPC Central Committee in September 1997.

Under the leadership of the third generation, the People's Republic of China gained sovereignty of Hong Kong and Macau in 1997 and 1999, respectively. The third generation also oversaw the PRC's accession into the World Trade Organization after 15 years of negotiations, and Beijing was awarded to host the 2008 Summer Olympics.

Economic development

China_Provincial_Migration.jpg

Zhu kept things on track in the difficult years of the late 1990s, so that mainland China averaged growth of 9.7% a year over the two decades to 2000. The ability of the PRC to chart an effective course through the recent Asian crisis was also noteworthy. Against the backdrop of the Asian financial crisis (and catastrophic domestic floods) mainland China's GDP still grew by 7.9% in the first nine months of 2002, beating the government's 7% target despite a global economic slowdown. This was achieved, partly, through active state intervention to stimulate demand through wage increases in the public sector, and other measures.

While foreign direct investment (FDI) worldwide halved in 2000, the flow of capital into mainland China rose 10%. As global firms scramble to avoid missing the China boom; FDI in China has risen 22.6% in 2002. While global trade stagnated, growing by one percent in 2002, mainland China's trade soared by 18% in the first nine months of 2002, with exports outstripping imports.

Zhu tackled deep-seated structural problems: uneven development; inefficient state firms and a banking system mired in bad loans. Observers think there are few substantial disagreements over economic policy in the CPC; tensions focus on the pace of change.

The PRC leadership is struggling to modernize state owned enterprises (SOEs) without inducing massive urban unemployment. As millions lost their jobs as state firms closed, Zhu demanded financial safety nets for unemployed workers. While mainland China will need 100 million new urban jobs in the next five years to absorb laid off workers and rural migrants; so far they have been achieving this aim due to high per capita GDP growth. Under the auspices of Zhu and Wen Jiabao (his top deputy and successor), the state has been alleviating unemployment while promoting efficiency by pumping tax revenues into the economy and maintaining consumer demand.

Critics have charged that there is an oversupply of manufactured goods, driving down prices and profits while increasing the level of bad debt in the banking system. But so far demand for Chinese goods, domestically and abroad, is high enough to put those concerns to rest in the time being. Consumer spending is growing, boosted, in large part, due to longer workers' holidays.

Zhu's right-hand man, Vice Premier Wen Jiabao oversaw regulations for the stock market, campaigned to develop poorer inland provinces to stem migration and regional resentment. Zhu and Wen have been setting tax limits for peasants to protect them from high levies by corrupt officials. Well respected by ordinary Chinese citizens, Zhu also holds the respect of Western political and business leaders, who found him reassuring and credit him with clinching China's market-opening World Trade Organisation (WTO) deal, which has brought foreign capital pouring into the country.

Zhu remained as Premier until the National People's Congress met in March 2003, when it approved his struggle to clinch trusted deputy Wen Jiabao as his successor. Like his forth-generation colleague Hu Jintao, Wen's personal opinions are difficult to discern since he sticks very closely to his script. Unlike the frank strong-willed Zhu, Wen, who has earned a reputation as an equally competent manager, is known for his suppleness and discretion.

| << | continued... >> |