History of women in the United States

|

|

U.S. History Timeline & Topics |

| Colonial America |

| 1776–1789 |

| 1789–1849 |

| 1849–1865 |

| 1865–1918 |

| 1918–1945 |

| 1945–1964 |

| 1964–1980 |

| 1980–1988 |

| 1988–present |

| Diplomatic history |

| Imperial history |

| Military history |

| Industrial history |

| Economic history |

| Cultural history |

| edit box (https://academickids.com:443/encyclopedia/index.php?title=Template:USHBS&action=edit) |

This is a history of feminism and the role of women throughout the history of the United States.

| Contents |

Women in colonial times

The experiences of women during the colonial era varied greatly from colony to colony. In New England, the Puritan settlers brought their strong religious values with them to the New World, which dictated that the wife be subordinate to her husband and dedicate herself to rearing God-fearing children to the best of her ability. In the early Chesapeake colonies, very few women were present. Much of the population consisted of young, single, white indentured servants, and as such the colonies to a large degree lacked any social cohesiveness. Much later on in the colonial experience, as the values of the Enlightenment were imported from Britain, the philosophies of such thinkers as John Locke weakened the view that husbands were natural "rulers" over their wives and replacing it with a (slightly) more liberal conception of marriage. Women also lost most control of their property when marrying.and even before then could not sue or be sued, could not make contracts, and divorce almost impossible until the late eighteenth century.

The Revolutionary period

The American Revolution had a deep effect on the philosophical underpinnings of American society. One aspect that was drastically changed by the democratic ideals of the Revolution was the roles of women. The idea of the republican mother was born in this period.

| Women of the era |

| Pocahontas |

| Anne Hutchinson |

| Anne Bradstreet |

| Eliza Lucas Pinckney |

| Martha Washington |

| Phillis Wheatley |

| Betsy Ross |

| Abigail Adams |

| Mother Ann Lee |

| "Molly Pitcher" |

| Deborah Sampson |

| Betty Zane |

The mainstream political philosophy of the day assumed that a republic rested upon the virtue of its citizens. Thus, women had the essential role of instilling their children with values conducive to a healthy republic. During this period, the wife's relationship with her husband also became more liberal, as love and affection instead of obedience and subservience began to characterize the ideal marital relationship. In addition, many women contributed to the war effort through fundraising and running family businesses in the absence of husbands.

Whatever gains they had made, however, women still found themselves subordinated, legally and socially, to their husbands, disenfranchised and with only the role of mother open to them. The desire of women to have a place in the new republic was most famously expressed by Abigail Adams to her husband:

- I desire you would remember the Ladies, and be more generous and favourable to them than your ancestors. Do not put such unlimited power into the hands of the Husbands.

The Cult of True Womanhood

During the 1830s and 1840s, many of the changes in the status of women that occurred in the post-Revolutionary period – such as the belief in love between spouses and the role of women in the home – continued at an accelerated pace. This was an age of reform movements, in which Americans sought to improve the moral fiber of themselves and of their nation in unprecedented numbers. The wife's role in this process was important because she was seen as the cultivator of morality in her husband and children. Besides domesticity, women were also expected to be pious, pure, and submissive to men. These four components were considered by many at the time to be "the natural state" of womanhood, echoes of this ideology still existing today. The view that the wife should find fulfillment in these values is called the Cult of True Womanhood or the Cult of Domesticity.

Early feminism

Early feminists active in the abolition movement increasingly began to compare women's situation with the plight of African American slaves. This new polemic squarely blamed men for all the restrictions of women's role, and argued that the relationship between the sexes was one-sided, controlling and oppressive.

Most of the early women's advocates were Christians, especially Quakers. It started with Lucretia Mott's involvement as one of the first women to join the Quaker abolitionist men in the abolitionist movement. The result was that Quaker women like Lucretia Mott learned how to organize and pull the levers of representative government. Starting in the mid-1830s, they decided to use those skills for women's advocacy. It was those early Quaker women who taught other women their advocacy skills, and for the first time used these skills for women's advocacy. As these new women's advocates began to expand on ideas about men and women, religious beliefs were also used to support them. Sarah Grimké suggested in her Letters on the Equality of the Sexes (1837) that the curse placed upon Eve in the Garden of Eden was God's prophecy of a period of universal oppression of women by men. Early feminists set about compiling lists of examples of women's plight in foreign countries and in ancient times.

Seneca Falls and the growth of the movement

At the Seneca Falls convention in 1848, Elizabeth Cady Stanton modeled her Declaration of Sentiments on the United States Declaration of Independence. Men were said to be in the position of a tyrannical government over women. This separation of the sexes into two warring camps was to become increasingly popular in feminist thought, despite some reform minded men such as William Lloyd Garrison and Wendel Phillips who supported the early women's movement.

As the movement broadened to include many women like Susan B. Anthony from the temperance movement, the slavery metaphor was joined by the image of the drunkard husband who batters his wife. Feminist prejudice that women were morally superior to men reflected the social attitudes of the day. It also led to the focus on women's suffrage over more practical issues in the latter half of the 19th century. Feminists assumed that once women had the vote, they would have the political will to deal with any other issues.

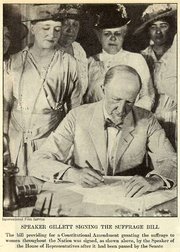

Victoria Woodhull argued in the 1870s that the 14th amendment to the United States Constitution already guaranteed equality of voting rights to women. She anticipated the arguments of the United States Supreme Court a century later. But there was a strong movement opposed to suffrage, and it was delayed another 50 years, during which time most of the practical issues feminists campaigned for, including the 18th amendment's prohibition on alcohol, had already been won.

Feminism during the Progressive Era

The growth of modern feminism

Stamp-ctc-women-support-the-war-effort.jpg

Feminism of the second wave in the 1960's focused more on lifestyle and economic issues; "The personal is the political" became a catchphrase. As the reality of women's status increased, the feminist rhetoric against men became more vitriolic. The dominant metaphor describing the relationship of men to women became rape; men raped women physically, economically and spiritually. Radical feminists argued that rape was the defining characteristic of men, and introduced a new phase of hostility to maleness. Lesbian separatists appealed to lesbian women, advocating the complete independence of women from what was seen as a male-dominated society.

Radical feminists, particularly Catharine MacKinnon, began to dominate feminist jurisprudence. Whereas first-wave feminism had concerned itself with challenging laws restricting women, the second wave tended to campaign for new laws that aimed to compensate women for societal discrimination. The idea of male privilege began to take on a legal status as judicial decisions echoed it, even in the United States Supreme Court.

One of the largest, earliest and most influential feminist organizations in the U.S., the National Organization for Women (NOW) illustrates the strong influence of radical feminism. Created in 1966 with Betty Friedan as president, the organization's name was deliberately chosen to say for women, and not of women. By 1968, the New York chapter lost many members who saw NOW as too mainstream. There was constant friction, most notably over the defense of Valerie Solanas. Solanas had shot Andy Warhol after writing the SCUM manifesto, seen by many as a passionately anti-male tract calling for the extermination of men. Ti-Grace Atkinson, the New York chapter president of NOW described her as, "the first outstanding champion of women's rights". Another member, Florynce Kennedy represented Solanas at her trial. Within a year of the split, the new group limited the number of women members who live with men to 1/3 of the group's membership. By 1971, all married women were excluded from the breakaway group and Atkinson had also defected.

Friedan denounced the lesbian radicals as the lavender menace and tried to distance NOW from lesbian activities and issues. The radicals accused her of homophobia. There was a constant fight for control of NOW which eventually Friedan lost. By 1992 Olga Vives, chair of the NOW's national lesbian rights taskforce estimated that 40 percent of NOW members were lesbians. However NOW remains open to male members in contrast to some groups.

In 1879, Belva Lockwood became the first woman to practice law before the U.S. Supreme Court, and in 1981, Sandra Day O'Connor became the first woman to become a member of the Supreme Court.