History of North Korea

|

|

Ac.dprkposter.jpg

Following World War II, Korea, which had been a colonial possession of Japan since 1910, was occupied by the Soviet Union (in the north) and the United States (in the south). After a period of political conflict the country was divided into the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (generally known in the west as North Korea) and the Republic of Korea (known as South Korea). See History of Korea for Korean history before 1948.

The Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK) was proclaimed on September 9, 1948, under the supervision of the occupying Soviet forces. Although there was an indigenous Korean Communist Party, the Soviets preferred to place in power Korean Communists who had spent the war years in the Soviet Union — this was also the policy they followed in eastern Europe. Accordingly, in February 1946, the leading Korean exile Communist, Kim Il-sung, was named as head of the North Korean Provisional People's Committee, which was superseded in 1948 by the DPRK. Kim then became Prime Minister, a post he held until 1972, when he became President. But the real centre of authority was the Korean Workers Party (KWP), of which Kim was General-Secretary.

| Contents |

Establishment of socialism

Template:History of Korea Kim's government moved rapidly to establish a Soviet-style system, with political power monopolised by the KWP. The establishment of a socialist economic system followed. Most of the country's productive assets had been owned by the Japanese or by Koreans held to have been collaborators. The nationalization of these assets in 1946 placed 70% of industry under state control. By 1949 this percentage had risen to 90%. Since then virtually all manufacturing, finance and internal and external trade has been conducted by the state.

In agriculture, on which the viability of an economy which was still basically agricultural depended, the government moved more slowly, but equally firmly, towards socialism. The land reform of 1946 redistributed the bulk of agricultural land to the poor and landless peasant population, an undoubtedly popular and beneficial move. In 1954, however, a partial collectivization was carried out, with peasants being urged, and often forced, into agricultural co-operatives. By 1958 virtually all farming was being carried out collectively, and the co-operatives were increasingly merged into larger productive units.

Like all the postwar Communist states, the DPRK undertook massive state investment in heavy industry, state infrastructure and military strength, neglecting the production of consumer goods. By paying the collectivized peasants low state-controlled prices for their product, and using the surplus thus extracted to pay for industrial development, the state carried out a series of three-year plans, which brought industry's share of the economy from 47% in 1946 to 70% in 1959, despite the intervening devastation of the Korean War. There were huge increases in electricity production, steel production and machine building. The large output of tractors and other agricultural machinery achieved a great increase in agricultural productivity.

As a result of these revolutionary changes, there is no doubt that the population was better fed and, at least in urban areas, better housed than they had been before the war, and also better than were most people in the South in this period. Even hostile observers agree that standards of living rose rapidly in the DPRK in the later 1950s and into the 1960s, certainly more rapidly than in the South, where there had been no land reform and little industrial development. There was, however, a chronic shortage of consumer goods, and the urban population lived under a system of extreme labor discipline and constant demands for greater productivity.

The Korean War

Ac.kimilsung1.jpg

Kim did not accept the division of Korean into two states. The consolidation of Syngman Rhee's government in the South and the suppression of the October 1948 insurrection there ended hopes that the country could be reunified by way of revolution in the South, and from 1949 Kim sought Soviet and Chinese support for a military campaign to reunify it by force. The almost total withdrawal of U.S. forces from South Korea in June 1949 left the South defended only by a weak and inexperienced Republic of Korea army. The DPRK army, by contrast, had been the beneficiary of massive expenditure and of Soviet tutelage, as well as having a core of hardened veterans who had fought as anti-Japanese guerillas or with the Chinese Communists.

The DPRK attacked the south on June 25, 1950, achieving total surprise, and rapidly captured Seoul and advanced to the south of the peninsula. At the time, it was assumed in the west that Joseph Stalin had ordered this attack, but it now seems likely that it was Kim's initiative, in which the Soviets and China acquiesced only reluctantly. DPRK forces were soon driven out of South Korea by United Nations forces led by the U.S. By October the U.N. forces had retaken Seoul and captured Pyongyang, and Kim and his government were forced to flee to China. But in November, Chinese forces entered the war and threw the U.N. forces back, retaking Pyongyang in December and Seoul in January 1951. In March U.N. forces retook Seoul, and the front was stabilised along what eventually became the permanent Armistice Line of 1953. (See Korean War for a detailed account.)

After the war Kim re-established his absolute domination of DPRK politics, with the crucial support of the armed forces, who respected his genuine wartime record of resistance to the Japanese, inflated by propaganda though it was. The leader of the South Korean Communists, Pak Hon-yong, was blamed for the failure of the southern population to support the DPRK during the war and was executed after a show-trial in 1955. Other potential rivals such as Kim Tu-bong were also purged.

Postwar consolidation

Ac.kimilsung3.jpg

The 1954-56 three-year plan repaired the damage caused by the war and brought industrial production back to pre-war levels. This was followed by the five-year plan of 1957-61 and the seven-year plan of 1961-67. These plans brought about further growth in industrial production and substantial development of state infrastructure. But by the 1960s the DPRK's economy was beginning to show the same signs of distortion that eventually affected all the Soviet-economies. In particular, the gap between urban and rural living standards widened and agricultural production stagnated.

The shortage of consumer goods and the decay in social infrastructure brought a decline in productivity despite harsh discipline. Most seriously, the massive and growing expenditure on armanents distorted the whole economy and led to increasing levels of debt. Since the Communist regime's hold on power ultimately depended on the loyalty of the army, it was not possible to restrain, let alone reduce, spending on the armed forces - a problem the DPRK shared with the Soviet Union and other Communist states. At the same time the DPRK's increasing international isolation made it difficult to expand foreign trade or secure credit.

The DPRK's position was complicated by the Sino-Soviet split, which began in 1960. Relations between the DPRK and the Soviet Union worsened when the Soviets concluded that Kim was supporting the Chinese side, although in fact Kim hoped to use the split to play China and the Soviets off against each other while pursuing a more independent policy. The result was a sharp decline in Soviet aid and credit, which could not be replaced by the less advanced Chinese even if China had been minded to do so. In fact Kim's enthusiasm for Mao Zedong's policies was limited, despite his rhetorical denunciations of "revisionism." While he supported Chinese campaigns such as the Great Leap Forward, he saw Maoist initiatives such as the Hundred Flowers Campaign and the Cultural Revolution as destabilising and dangerous.

As an alternative, Kim promoted Juche ("self-reliance"), a slogan he began to develop in the late 1950s and which he ultimately made the DPRK's official ideology, displacing Marxism-Leninism. This policy was to a large extent making a virtue of a necessity, since the DPRK's isolation from the world economy and its alienation from the Soviet Union left it with few friends or sources of support in the outside world. As a result the DPRK became increasingly introverted, and was dubbed "the hermit kingdom" by some foreign observers. To shore up his position, Kim fostered an increasingly bizarre personality cult around himself and his family, coming to be known by titles such as the "Great Leader" and worshipped in a god-like fashion by the state media.

Gathering crisis

In the 1970s the expansion of the DPRK's economy, with the accompanying rise in living standards, came to an end and then went into reverse. There were a number of reasons for this. One was the huge increase in the price of oil following the oil shock of 1974. The DPRK has no oil of its own, and since it had few export commodities of interest to the west, it could not afford to pay for oil imports - this was the downside of Juche. Secondly the huge levels of state expenditure on armaments could no longer be sustained, but for political reasons could not be reduced. In fact Kim's stated determination to achieve the reunification of Korea in his lifetime meant that military expenditure could only increase.

Most importantly, however, the Soviet-style command economy, based on heavy industry, had reached the limits of its productive potential in the DPRK, as it had in the Soviet Union and elsewhere. By the 1970s the capitalist world, including South Korea, was advancing into new phases of technology and economic development and phasing out the coal-and-steel-based economies of the earlier period. This gave the United States and Japan a huge and increasing technological and economic advantage over the Soviet-style economies, and during the presidency of Ronald Reagan this was translated into a corresponding military advantage.

One of the consequences of this new phase of capitalist development was the export of manufacturing jobs to low-wage economies, and South Korea was one of the main beneficiaries of this. Until the 1970s the South had had a poorly performing economy, held back by corruption and inefficiency. Under Park Chung-hee, however, there had been major economic reforms in the South, and this, combined with the export of capital from the high-wage economies, produced a self-reinforcing boom in the South which began in about 1980 and has continued ever since. After the fall of Chun Doo-hwan in 1988, South Korea became a stable democracy, increasing the contrast with the unreformed Stalinist regime in the North.

The ageing Kim Il-sung was unable to respond effectively to the challenge of an increasingly prosperous, democratic and well-armed South Korea, which undermined the legitimacy of his own regime. Instead of turning to market-economy reforms like those carried out in China by Deng Xiaoping, Kim opted for continued ideological purity and isolation from the outside world, coupled with increasingly belligerent rhetoric towards South Korea, Japan and the U.S. The DPRK defaulted on its loans in 1980 and by the late 1980s its industrial output was declining.

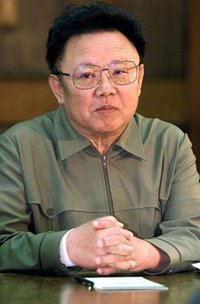

Kim Jong-il's regime

Kim Il-sung died in 1994, and his son, Kim Jong-il, succeeded him as General-Secretary of the Korean Workers Party. Although the post of President was left vacant, Kim Jong-il became Chairman of the National Defense Commission, a position described as the nation's "highest administrative authority," and thus the DPRK's de facto head of state. His succession had been decided as early as 1980, with the support of the most important interest group, the armed forces led by Defence Minister Oh Jin-wu.

During the decade of Kim Jong-il's rule, the DPRK's economy has continued to deteriorate and the standard of living of its 22 million people has continued to fall. The fundamental cause of this decline is that the state, which runs the entire economy, is bankrupt, and cannot pay for the necessary imports of capital goods to undertake the desperately needed modernisation of its industrial plant. The DPRK spends a third of its GDP on armaments, including the development of nuclear weapons, and keeps one-fifth of males aged 18-45 in uniform, while the basic infrastructure of the state is allowed to crumble.

As a result, the DPRK is now dependent on international food aid to feed its population. According to Amnesty International, more than 13 million people suffered from malnutrition in the DPRK in 2003. In 2001 the DPRK received nearly $US300 million in food aid from the U.S., South Korea, Japan, and the European Union, plus much additional aid from the United Nations and non-governmental organizations. Despite this the DPRK maintained its violent rhetoric against the U.S., South Korea and Japan. The supply of heating and electricity outside the capital is practically non-existent, and food and medical supplies are scarce. When there is a bad harvest, as has been persistently the case over recent years, the population faces actual famine: a situation never before seen in a peacetime industrial economy. Since 2000 there has been a steady stream of emigration to China, despite the efforts of both countries to prevent it.

Kim's regime has said that the solution to this crisis is earning hard currency, developing information technology and attracting foreign aid, but despite some gestures towards reform it has made no real progress towards reducing the state's control over the economy or introducing the market-oriented reforms which have produced such spectacular economic growth in China since 1979, and are now doing the same in Vietnam. Without these reforms the regime's strategy for recovery remains unattainable. So far the DPRK, not surprisingly, has made little progress in attracting private capital.

In July 2002 some limited reforms were announced. The currency was devalued and food prices were allowed to rise in the hope of stimulating agricultural production. It was announced that food rationing systems as well as subsidized housing would be phased out. A "family-unit farming system" was introduced on a trial basis for the first time since collectivization in 1954. The government also set up a "special administrative zone" in Sinuiju, a town near the border with China. The local authority was given near-autonomy, especially in its economic affairs. This was an attempt to emulate the success of such free-trade zones in China, but it attracted little outside interest. Despite some optimistic talk in the foreign press the impetus of these reforms has not been followed through with, for example, a large-scale decollectivization such as occurred in China under Deng.

Current situation

During the presidency of Kim Dae-jung in South Korea, there was an attempt by reduce tensions between the two Koreas and unfreeze the political situation on the peninsula, but this produced few practical results. Since the election of George W. Bush as President of the United States, the DPRK has faced renewed external pressure over its nuclear program, reducing the prospect of international economic assistance.

Meanwhile, the DPRK remains what it had been since 1948, a Stalinist-style state in which all political, religious and intellectual freedom is denied. No political opposition of any kind is tolerated. The lack of access to the foreign media and the tradition of secrecy in the DPRK means that there is little news about political conditions, but Amnesty International's 2003 report on the DPRK says that "there were reports of severe repression of people involved in public and private religious activities, including imprisonment, torture and executions. Unconfirmed reports suggested that torture and ill-treatment were widespread in prisons and labour camps. Conditions were reportedly extremely harsh."

Despite all these problems, there seems little immediate prospect that the DPRK will undergo an East German-style collapse: a prospect that South Korea views with great trepidation. On the other hand, it is hard to see the current situation continuing indefinitely. An international bailout, which may be the best way to bring about a "managed transition" of the DPRK, would only be possible with the co-operation of the U.S., and that seems unlikely under the Bush administration unless North Korea agrees on solving international concerns about its nuclear arsenal. It would also require a clear commitment to fundamental reform from the DPRK, something with Kim Jong-il seems unwilling or unable to give.

There appears to be no internal opposition to the regime, despite the acute hardships been undergone by its people: a tribute to the all-pervading personality cult of the Kim family over two generations as well as a consequence of the extremely harsh repression with which the DPRK deals with any kind of behaviour not approved by the government. The only group with the capacity to act autonomously of the KWP is the army, and a military coup is thus one possible way the Kim regime could be overthrown. Since any reform of the DPRK would inevitably reduce the army's power and wealth, however, this would be a difficult course for it to follow.

North Korea declared on Feb. 10, 2005 that it has nuclear weapons [1] (http://www.kcna.co.jp/item/2005/200502/news02/11.htm#1) bringing widespread expressions of dismay and near-universal calls for the North to return to the six-party negotiations aimed at curbing its nuclear program.

"Their nuclear capability was never really doubted, and they didn't really give us any new information to raise our concerns," said Michael O'Hanlon, a foreign policy specialist at the Brookings Institution who is the author of "Crisis on the Korean Peninsula." "They didn't tell us they had weapons that can fit on top of missiles," he said. "They didn't tell us how many weapons they had. They didn't test a weapon. There were a lot of things they could've done that would have been worse.

"I think whatever damage occurred today can be walked back," he said. "I don't think the North Koreans are suicidal." [2] (http://www.iht.com/bin/print_ipub.php?file=/articles/2005/02/10/news/react.html)

See also

External link

- Speak Out About Human Rights In North Korea (http://hrw.org/english/docs/2004/04/16/nkorea8445.htm) (a commentary from Human Rights Watch, published in The Asian Wall Street Journal, April 16, 2004)pt:História da Coreia do Norte