Deng Xiaoping

|

|

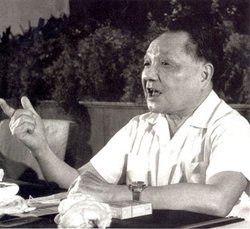

Deng Xiaoping Template:Audio (Template:Zh-stpw; pronounced "Dung Shyao-ping"; August 22, 1904—February 19, 1997) was a revolutionary elder in the Communist Party of China (CPC) who served as the de facto ruler of the People's Republic of China from the late 1970s to the early 1990s, forming the core of the "second generation" CPC leadership. Under his tutelage, China developed one of the fastest growing economies in the world.

| Contents |

Background

Deng was born Deng Xixian (鄧希賢 / 邓希贤) in Paifang Village in Xiexing township, Guang'an County, Sichuan Province. He was educated in France, participating in a work-study program for Chinese students, where many notable Asian revolutionaries, such as Ho Chi Minh and Zhou Enlai, discovered Marxism-Leninism.

Deng married 3 times. His first wife, Zhang Xiyuan, one of his schoolmates from Moscow, died when she was 24, a few days after giving birth to Deng's first child, a baby girl, who also died. His second wife, Jin Weiying, left him after he came under political attack in 1933.

His third wife, Zhuo Lin, was the daughter of an industrialist in Yunnan Province. She became a member of the Communist Party in 1938, and a year later married Deng in front of Mao's cave dwelling in Yan'an. They had 5 children: 3 daughters (Deng Lin, Deng Nan, Deng Rong) and 2 sons (Deng Pufang, Deng Zhifang).

Early career

He joined the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) while he was a student, becoming a member of the China Socialist Youth League in 1922 and studying in Moscow for several months in 1926. He was a veteran of the Long March, during which Deng served as General Secretary of the Central Committee. While acting as political commissar for Liu Bocheng, he organized several important military campaigns during the war with Japan and during the Civil War against the Kuomintang. As an old fellow combatant and supporter of Mao Zedong, Deng was named by Mao to several important posts, including General Secretary of the Communist Party, soon after the Revolution.

After officially supporting Mao Zedong in his Anti-Rightist Campaign of 1957, Deng became General Secretary of the Communist Party of China and ran the country's daily affairs with then President Liu Shaoqi. Amid growing disenchantment with Mao's Great Leap Forward, Deng and Liu gained influence within the CPC. They embarked on economic reforms that bolstered their prestige among the party apparatus and the national populace. Deng and Liu followed more progressive policies, as opposed to Mao's radicalist ideas.

Mao grew apprehensive that such prestige could lead to himself being reduced to a mere figurehead. Amongst other reasons, Mao launched the Cultural Revolution in 1966, during which Deng fell out of favor and was forced to retire from all his offices. He was sent to a rural engines factory in Sichuan to work as a regular worker. While there Deng spent his spare time writing. He was purged nationally, but to a lesser scale than Liu Shaoqi.

With Premier Zhou Enlai ill from cancer, Deng became Zhou's choice for a successor, and Zhou was able to convince Mao to bring Deng Xiaoping back into politics in 1974 as First Deputy Premier, in practice running daily affairs. However, the Cultural Revolution was not yet over, and a radicalist political group called the Gang of Four caused a lot of power struggle. The Gang saw Deng as their greatest challange to success. After Zhou's death in January 1976, Deng lost firm support in the party, and after delivering Zhou's official eulogy at the state funeral, was purged once again. Deng was forced to give up all posts by the Gang of Four.

Reemergence of Deng

A strong-willed and highly intelligent peasant revolutionary, the diminutive and aging Deng gradually emerged as the de-facto leader of the world's most populous nation in the few years following Mao's death in 1976. Deng was also one of only a handful of peasant revolutionaries to lead China, a group that includes Mao Zedong and the founders of the Han and Ming dynasties.

By carefully mobilizing his supporters within the Chinese Communist Party, Deng was able to outmaneuver Mao's anointed successor Hua Guofeng, who had previously pardoned him, and then oust Hua from his top leadership positions by 1980-1981. In contrast to previous leadership changes, Deng allowed Hua, who is still alive and retained membership in the Central Committee until November 2002, to quietly retire, and helped to set a precedent that losing a high-level leadership struggle would not result in physical harm.

Deng then repudiated the Cultural Revolution and launched the "Beijing Spring," which allowed open criticism of the excesses and suffering that had occurred during the period. Meanwhile, he was the impetus for the abolishment of the class background system. Under this system, the CPC put up employment barriers to Chinese deemed associated with the former landlord class.

Deng gradually outmaneuvered his political opponents. By encouraging public criticism of the Cultural Revolution, he weakened the position of those who owed their political positions to that event, while strengthening the position of those like himself who had been purged during that time. Deng also received a great deal of popular support.

As Deng gradually consolidated control over the CPC, Hua was replaced by Zhao Ziyang as premier in 1980, and by Hu Yaobang as party chief in 1981. Deng remained the most influential CPC cadre, although after 1987 his only official posts were as chairman of the state and Communist Party Central Military Commissions.

Originally, the president was conceived of as a figurehead head of state, with actual state power resting in the hands of the premier and the party chief, both offices being conceived of as held by separate people in order to prevent a cult of personality from forming (as it did in the case of Mao); the party would develop policy, whereas the state would execute it. Ironically, Deng held none of these top posts.

Opening up

Under Deng's direction, relations with the West improved markedly. Deng traveled abroad and had a series of amicable meetings with western leaders, traveling to the United States in 1979 to meet President Carter at the White House shortly after the U.S. broke diplomatic relations with the Republic of China and established them with the PRC. Sino-Japanese relations also improved significantly. Deng used Japan as an example of a rapidly progressing economic power that sets a good example for China's future economic directions.

Another achievement was the agreement signed by Britain and China on December 19, 1984 (Sino-British Joint Declaration) under which Hong Kong was to be handed over to the PRC in 1997. With the end of the 99-year lease on the New Territories expiring, Deng agreed that the PRC would not interfere with Hong Kong's capitalist system for 50 years. A similar agreement was signed with Portugal for the return of colony Macau. Dubbed "one country-two systems," this approach has been touted by the PRC as potential framework within which Taiwan could be reunited with the Mainland in more recent years.

Deng, however, did little to improve relations with the Soviet Union, continuing to adhere to the Maoist line of the Sino-Soviet Split era that the Soviet Union was a superpower equally as "hegemonist" as the United States, but even more threatening to China because of its closer proximity.

"Socialism with Chinese characteristics"

The goals of Deng's reforms were summed up by the Four Modernizations, those of agriculture, industry, science and technology and the military. The strategy for achieving these aims of becoming a modern, industrial nation was the socialist market economy.

Deng argued that China was in the primary stage of socialism and that the duty of the party was to perfect "socialism with Chinese characteristics." This interpretation of Chinese Marxism reduced the role of ideology in economic decision-making and deciding policies of proven effectiveness. Downgrading communitarian values but not necessarily Marxism-Leninism, Deng emphasized that socialism does not mean shared poverty.

Unlike Hua Guofeng, Deng believed that no policy should be rejected out of hand simply for not having been associated with Mao, and unlike more conservative leaders such as Chen Yun, Deng did not object to policies on the grounds that they were similar to ones which were found in capitalist nations.

Although Deng provided the theoretical background and the political support to allow economic reform to occur, few of the economic reforms that Deng introduced were originated by Deng himself. Typically a reform would be introduced by local leaders, often in violation of central government directives. If successful and promising, these reforms would be adopted by larger and larger areas and ultimately introduced nationally. Many other reforms were influenced by the experiences of the East Asian Tigers.

This is in sharp contrast to the pattern in the perestroika undertaken by Mikhail Gorbachev in which most of the major reforms were originated by Gorbachev himself. The bottom-up approach of the Deng reforms, in contrast to the top-down approach of perestroika, was likely a key factor in the success of the former.

Deng's reforms actually included the introduction of planned, centralized management of the macro-economy by technically proficient bureaucrats, abandoning Mao's mass campaign style of economic construction. However, unlike the Soviet model, management was indirect through market mechanisms.

Deng sustained Mao's legacy to the extent that he stressed the primacy of agricultural output and encouraged a significant decentralization of decision making in the rural economy teams and individual peasant households. At the local level, material incentives, rather than political appeals, were to be used to motivate the labor force, including allowing peasants to earn extra income by selling the produce of their private plots at free market.

In the main move toward market allocation, local municipalities and provinces were allowed to invest in industries that they considered most profitable, which encouraged investment in light manufacturing. Thus, Deng's reforms shifted China's development strategy to an emphasis on light industry and export-led growth.

Light industrial output was vital for a developing country coming from a low capital base. With the short gestation period, low capital requirements, and high foreign-exchange export earnings, revenues generated by light manufacturing were able to be reinvested in more technologically-advanced production and further capital expenditures and investments.

However, in sharp contrast to the similar but much less successful reforms in Yugoslavia and Hungary, these investments were not government mandated. The capital invested in heavy industry largely came from the banking system, and most of that capital came from consumer deposits. One of the first items of the Deng reforms was to prevent reallocation of profits except through taxation or through the banking system; hence, the reallocation in state-owned industries was somewhat indirect, thus making them more or less independent from the government interference. In short, Deng's reforms sparked an industrial revolution in China.

These reforms were a reversal of the Maoist policy of economic self-reliance. China decided to accelerate the modernization process by stepping up the volume of foreign trade, especially the purchase of machinery from Japan and the West. By participating in such export-led growth, China was able to step up the Four Modernizations by attaining certain foreign funds, market, advanced technologies and management experiences, thus accelerating its economic development.

Deng attracted foreign companies to a series of special Economic Zones, where foreign investment and market liberalization were encouraged.

The reforms centered on improving labor productivity as well. New material incentives and bonus systems were introduced. Rural markets selling peasants' homegrown products and the surplus products of communes were revived. Not only did rural markets increase agricultural output, they stimulated industrial development as well. With peasants able to sell surplus agricultural yields on the open market, domestic consumption stimulated industrialization as well and also created political support for more difficult economic reforms.

There are some parallels between Deng's market socialism especially in the early stages, and Lenin's New Economic Policy as well as those of Bukharin's economic policies, in that both foresaw a role for private entrepreneurs and markets based on trade and pricing rather than central planning.

An interesting anecdote on this note is the first meeting between Deng and Armand Hammer. Deng pressed the industrialist and former investor in Lenin's Soviet Union for as much information on the NEP as possible.

The Tiananmen Square Crackdown

While reforming and opening up the economy, Deng attempted to strengthen the power of the Communist Party by regularization of procedure, but is widely regarded as having undermined his own intentions by acting contrary to party procedure.

In the late 1980s, Deng Xiaoping attempted the implementation of a system where the Party develops policy and the State executes it, with the President and Party Secretary being two different people, and the President acting as mostly a figurehead. Deng's subsequent actions caused the presidency to have much larger powers than were originally intended. In 1989, President Yang Shangkun was able in cooperation with the then-head of the Central Military Commission, Deng Xiaoping, to use the office of the President to declare martial law in Beijing and order the military crackdown of the Tiananmen Square protests of 1989. This was in direct opposition to the wishes of the Party General Secretary Zhao Ziyang and probably a majority of the Politburo Standing Committee. The decision went ahead regardless, leading to army intervention.

Zhao's opposition and "attempts to divide the party" made him disgraced politically. Deng subsequently selected Jiang Zemin over Tianjin's Li Ruihuan as a compromise candidate and other party elders to replace Zhao, who was considered too conciliatory to student protesters. Although not directly involved with the crackdown, Jiang was elevated to central party positions after the Tiananmen Square protests of 1989 for his role in averting similar protests in Shanghai.

Internationally, China was damaged significantly from the crackdown of the Tiananmen Protests, and Deng was held with the greatest responsibility. Trade embargos were enforced by nations of the European Union, the United States and other countries. China was once again isolated after years of recovery in the area of foreign affairs.

After Resignation

Officially, Deng decided to retire from top positions when he stepped down as Chairman of the Central Military Commission in 1989, and retired from the political scene in 1992. China, however, was still in the era of Deng Xiaoping. He continued to maintain his position as paramount leader of the country, believed to have backroom control. Hu Jintao, Deng's hand-picked man, is now the leader the fourth generation of PRC Leadership. Deng was recognized officially as "The architect of China's economic reforms and China's socialist modernization". To the Communist Party, he was believed to have set a good example for communist cadres refusing to retire at old age. He broke earlier conventions of holding offices for life. He was often referred to as simply Comrade Xiaoping, with no title attatched.

In the spring of 1992, Deng went on a southern tour of China, visiting Guangzhou, Shenzhen, Zhuhai and Shanghai, making various speeches. He stressed the importance of economic construction in China, and criticized those who were against the reforms and opening up. He stated that "leftist" elements of Chinese society were much more dangerous than "rightist" ones. He maintained that the economic reforms was a policy unchangeable in China, and essential to China's further development. His southern tour was followed closely by Chinese media, and was taken very seriously by local officials. Many people recognized the southern tour as a new achievement, making up for the mistake in the Tiananmen Crackdown.

Death and reaction

Deng Xiaoping died on February 19, 1997, at age 92, but his influence continued. At 1.5 meters (4 feet 11 inches), Chinese often called him "The Short Giant"(矮巨人) as Deng was short yet powerful. Even though Jiang Zemin was in firm control, the applicable policies still followed Deng's ideas, thoughts, methods, and direction. The Central Government called Deng the "Great Marxist, Great Proletarian Revolutionary, politician, militarist, diplomat; one of the main leaders of the Communist Party of China, the People's Liberation Army of China, and the People's Republic of China; The great architect of China's socialist opening-up and modernized construction; the founder of Deng Xiaoping theory." Solemn tunes of funeral music played on television, radio and on the streets. China was in an official state of mourning. On February 19, the CCTV Xinwen Lianbo at 7PM was extended for around three hours from the normal half-hour time. News coverage was lengthened for a week for the events related to Deng's death.

At 10 AM on the morning of February 24, from all walks of life in the whole nation, people paused in silence in unison for three minutes. The nation's flags flew at half-mast for over a week. During the nationally televised funeral of Deng that was broadcast on all cable channels, Jiang Zemin's emotional eulogy to the late reformist leader declared, "The Chinese people love Comrade Deng Xiaoping, thank Comrade Deng Xiaoping, mourn for Comrade Deng Xiaoping, and cherish the memory of Comrade Deng Xiaoping because he devoted his life-long energies to the Chinese people, performed immortal feats for the independence and liberation of the Chinese nation." Jiang vowed to continue Deng's policies. After the funeral, Deng was cremated and his ashes were subsequently sent into China's rivers, according to his wishes.

There was a significant amount of international reaction to Deng's death. UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan said Deng was to be remembered "in the international community at large as a primary architect of China's modernization and dramatic economic development." French President Jacques Chirac said "In the course of this century, few men have, as much as [Deng Xiaoping], led a vast human community through such profound and determining changes," British Prime Minister John Major commented about Deng's key role in the return of Hong Kong to Chinese control. The Taiwan presidential office also sent its condolences, saying it longed for peace, cooperation, and prosperity. The Dalai Lama voiced regret.

In the year that followed, songs like "Story of the Spring" by Dong Yuanhua were created in Deng's honour. The CCTV-1 network ran a lengthy documentary series on Deng's life.

Legacy

According to journalist Jim Rohwer, "the Dengist reforms of 1979–1994 brought about probably the biggest single improvement in human welfare anywhere at any time." This improvement was due to the fact that the reforms affected hundreds of millions of people.

As mentioned, Deng's policies opened up the economy to foreign investment and market allocation within a socialist framework. Since his death, under Jiang's tutelage, China has sustained a reported average of 8% GDP growth annually, achieving one of the world's highest rate of per capita economic growth, if not the highest. The inflation characteristic of the years leading up to the Tiananmen protests has subsided. Political institutions have stabilized, thanks to the institutionalization of procedure of the Deng years and a generational shift from peasant revolutionaries to well-educated, professional technocrats. Social problems have eased as well, as mainland China rapidly becomes more modern and prosperous each year.

Deng's reforms, however, have left a number of issues unresolved. As a result of his market reforms, it became obvious by the mid-1990s that many state-owned enterprises (owned by the central government, unlike TVEs publicly owned at the local level) were unprofitable and needed to be shut down if they were not to be a permanent and unsustainable drain on the economy. Furthermore, by the mid-1990s most of the benefits of Deng's reforms particularly in agriculture had run their course, rural incomes had become stagnant, leaving China's leaders in search of new means to boost economic growth or else risk a massive social explosion.

ChinaDeng.jpg

Finally, the Dengist policy of asserting the primacy of pragmatism over communitarian Maoist values, while maintaining the rule of the Communist Party, raised questions in the West. Many observers both within China and outside question the degree to which a one-party system can indefinitely maintain control over an increasingly dynamic and prosperous Chinese society. For these political and economic influences, among other things, Deng was named TIME's Man of the Year for two years.

External links

- Selected Works of Deng Xiaoping (http://english.peopledaily.com.cn/dengxp/)

- Life of Deng Xiaoping (http://www.cbw.com/asm/xpdeng/contents.html)

- China officially mourns Deng Xiaoping (http://www.cnn.com/WORLD/9702/24/china.deng/) (from CNN)

- Deng's Free Market Nightmare (http://rwor.org/a/firstvol/890-899/896/capchi.htm) (Maoist criticism)

- China 2002: Building socialism with Chinese characteristics (http://www.pww.org/article/articleview/899/1/68/) (Communist Party USA)

- China Daily Biography (http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/english/doc/2004-06/25/content_342508.htm)

| Preceded by: None | General Secretary of the Communist Party of China 1956–1957 | Succeeded by: Hu Yaobang |

| Preceded by: Hua Guofeng | Chairman of the Central Military Commission of CCP 1981–1989 | Succeeded by: Jiang Zemin |

| Preceded by: None | Chairman of the Central Military Commission of PRC 1983–1990 | Succeeded by: Jiang Zemin Template:End boxde:Deng Xiaoping es:Deng Xiaoping eo:DENG Xiaoping fr:Deng Xiaoping ko:덩샤오핑 he:דנג שיאופינג zh-min-nan:Tēng Siáu-pêng nl:Deng Xiaoping ja:トウ小平 pl:Deng Xiaoping pt:Deng Xiaoping fi:Deng Xiaoping sv:Deng Xiaoping zh:邓小平 |