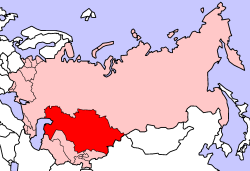

History of Kazakhstan

|

|

Native Kazakhs, a mix of Turkic and Mongol nomadic tribes who migrated into the region in the 13th century, were rarely united as a single nation. The area was conquered by Russia in the 18th century and Kazakhstan became a Soviet Republic in 1936.

1917-18: Alash Orda State in Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan.

During the 1950s and 1960s agricultural "Virgin Lands" program, Soviet citizens were encouraged to help cultivate Kazakhstan's northern pastures. This influx of immigrants (mostly Russians, but also some other deported nationalities) skewed the ethnic mixture and enabled non-Kazakhs to outnumber natives.

Independence in 1991 caused many of these newcomers to emigrate. Current issues include: developing a cohesive national identity; expanding the development of the country's vast energy resources and exporting them to world markets; achieving a sustainable economic growth outside the oil, gas, and mining sectors; and strengthening relations with neighboring states and other foreign powers.

| Contents |

Background

By far the largest of the Central Asian republics of the former Soviet Union, independent Kazakhstan is the world's ninth-largest nation in geographic area. The population density of Kazakhstan is among the lowest in the world, partly because the country includes large areas of inhospitable terrain. Kazakhstan is located deep within the Asian continent, with coastline only on the landlocked Caspian Sea. The proximity of unstable countries such as Afghanistan, Tajikistan, and Azerbaijan to the west and south further isolates Kazakhstan.

Within the centrally controlled structure of the Soviet system, Kazakhstan played a vital industrial and agricultural role; the vast coal deposits discovered in Kazakhstani territory in the twentieth century promised to replace the depleted fuel reserves in the European territories of the union. The vast distances between the European industrial centers and coal fields in Kazakhstan presented a formidable problem that was only partially solved by Soviet efforts to industrialize Central Asia. That endeavor left the newly independent Republic of Kazakhstan a mixed legacy: a population that includes nearly as many Russians as Kazakhs; the presence of a dominating class of Russian technocrats, who are necessary to economic progress but ethnically unassimilated; and a well-developed energy industry, based mainly on coal and oil, whose efficiency is inhibited by major infrastructural deficiencies.

Kazakhstan has followed the same general political pattern as the other four Central Asian states. After declaring independence from the Soviet political structure completely dominated by Moscow and the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) until 1991, Kazakhstan retained the basic governmental structure and, in fact, most of the same leadership that had occupied the top levels of power in 1990. Nursultan Nazarbayev, first secretary of the Communist Party of Kazakhstan (CPK) beginning in 1989, was elected president of the republic in 1991 and remained in undisputed power five years later. Nazarbayev took several effective steps to ensure his position. The constitution of 1993 made the prime minister and the Council of Ministers responsible solely to the president, and in 1995 a new constitution reinforced that relationship. Furthermore, opposition parties were severely limited by legal restrictions on their activities. Within that rigid framework, Nazarbayev gained substantial popularity by limiting the economic shock of separation from the security of the Soviet Union and by maintaining ethnic harmony, despite some discontent among Kazakh nationalists and the huge Russian minority.

In the mid-1990s, Russia remained the most important sponsor of Kazakhstan in economic and national security matters, but in such matters Nazarbayev also backed the strengthening of the multinational structures of the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), the loose confederation that succeeded the Soviet Union. As sensitive ethnic, national security, and economic issues cooled relations with Russia in the 1990s, Nazarbayev cultivated relations with China, the other Central Asian nations, and the West. Nevertheless, Kazakhstan remains principally dependent on Russia.

Kazakhstan entered the 1990s with vast natural resources, an underdeveloped industrial infrastructure, a stable but rigid political structure, a small and ethnically divided population, and a commercially disadvantageous geographic position. In the mid-1990s, the balance of those qualities remained quite uncertain.

Historical Setting

Until the arrival of Russians in the 18th century, the history of Kazakhstan was determined by the movements, conflicts, and alliances of Turkic and Mongol tribes. The nomadic tribal society of what came to be the Kazakh people then suffered increasingly frequent incursions by the Russian Empire, ultimately being included in that empire and the Soviet Union that followed it.

Early Tribal Movements

Humans have inhabited present-day Kazakhstan since the earliest Stone Age, generally pursuing the nomadic pastoralism for which the region's climate and terrain are best suited. The earliest well-documented state in the region was the Turkic Kaganate, created by Mongolian tribe A-Shono (tribe of "Wolf"), which came into existence in the 6th century AD. The Qarluqs, a confederation of Turkic tribes, established a state in what is now eastern Kazakhstan in 766. In the 8th and 9th centuries, portions of southern Kazakhstan were conquered by Arabs, who also introduced Islam. The Oghuz Turks controlled western Kazakhstan from the 9th through the 11th centuries; the Kimak and Kipchak peoples, also of Turkic origin, controlled the east at roughly the same time. The large central desert of Kazakhstan is still called Dashti-Kipchak, or the Kipchak Steppe.

In the late 9h century, the Qarluq state was destroyed by invaders who established the large Qarakhanid state, which occupied a region known as Transoxiana, the area north and east of the Oxus River (the present-day Amu Darya), extending into what is now China. Beginning in the early 11th century, the Qarakhanids fought constantly among themselves and with the Seljuk Turks to the south. In the course of these conflicts, parts of present-day Kazakhstan shifted back and forth between the combatants. The Qarakhanids, who accepted Islam and the authority of the Arab Abbasid caliphs of Baghdad during their dominant period, were conquered in the 1130s by the Karakitai, a Turkic confederation from northern China. In the mid-12th century, an independent state of Khorazm along the Oxus River broke away from the weakening Karakitai, but the bulk of the Karakitai state lasted until the invasion of Genghis Khan in 1219-1221.

After the Mongol capture of the Karakitai state, Kazakhstan fell under the control of a succession of rulers of the Mongolian Golden Horde, the western branch of the Mongol Empire. (The horde, or zhuz, is the precursor of the present-day clan, which is still an important element of Kazakh society). By the early 15th century, the ruling structure had split into several large groups known as khanates, including the Nogai Horde and the Uzbek Khanate.

Forming the Modern Nation

The present-day Kazakhs became a recognizable group in the mid-15th century, when clan leaders broke away from Abul Khayr, leader of the Uzbeks, to seek their own territory in the lands of Semirechie, between the Chu and Talas rivers in present-day southeastern Kazakhstan. The first Kazakh leader was Khan Kasym (r. 1511-1523), who united the Kazakh tribes into one people. In the 16th century, when the Nogai Horde and Siberian khanates broke up, clans from each jurisdiction joined the Kazakhs. The Kazakhs subsequently separated into three new hordes: the Great Horde, which controlled Semirech'ye and southern Kazakhstan; the Middle Horde, which occupied north-central Kazakhstan; and the Lesser Horde, which occupied western Kazakhstan.

Russian traders and soldiers began to appear on the northwestern edge of Kazakh territory in the 17th century, when Cossacks established the forts that later became the cities of Oral (Ural'sk) and Atyrau (Gur'yev). Russians were able to seize Kazakh territory because the khanates were preoccupied by Kalmyk invaders of Mongol origin, who in the late 16th century had begun to move into Kazakh territory from the east. Forced westward in what they call their Great Retreat, the Kazakhs were increasingly caught between the Kalmyks and the Russians. Two of Kazakh Hordes were depend of Oirat Huntaiji. In 1730 Abul Khayr, one of the khans of the Lesser Horde, sought Russian assistance. Although Abul Khayr's intent had been to form a temporary alliance against the stronger Kalmyks, the Russians gained permanent control of the Lesser Horde as a result of his decision. The Russians conquered the Middle Horde by 1798, but the Great Horde managed to remain independent until the 1820s, when the expanding Kokand Khanate to the south forced the Great Horde khans to choose Russian protection, which seemed to them the lesser of two evils.

The Kazakhs began to resist Russian control almost as soon as it became complete. The first mass uprising was led by Khan Kene (Kenisary Kasimov) of the Middle Horde, whose followers fought the Russians between 1836 and 1847. Khan Kene is now considered a Kazakh national hero.

Russian Control

In 1863 Russia elaborated a new imperial policy, announced in the Gorchakov Circular, asserting the right to annex "troublesome" areas on the empire's borders. This policy led immediately to the Russian conquest of the rest of Central Asia and the creation of two administrative districts, the General-Gubernatorstvo (Governor-Generalship) of Russian Turkestan and that of the Steppe. Most of present-day Kazakhstan was in the Steppe District, and parts of present-day southern Kazakhstan, including Almaty (Verny), were in the Governor-Generalship.

In the early 19th century, the construction of Russian forts began to have a destructive effect on the Kazakh traditional economy by limiting the once-vast territory over which the nomadic tribes could drive their herds and flocks. The final disruption of nomadism began in the 1890s, when many Russian settlers were introduced into the fertile lands of northern and eastern Kazakhstan. In 1906 the Trans-Aral Railway between Orenburg and Tashkent was completed, further facilitating Russian colonisation of the fertile lands of Semirechie. Between 1906 and 1912, more than a half-million Russian farms were started as part of the reforms of Russian minister of the interior Petr Stolypin, putting immense pressure on the traditional Kazakh way of life by occupying grazing land and using scarce water resources.

Starving and displaced, many Kazakhs joined in the general Central Asian Revolt against conscription into the Russian imperial army, which the tsar ordered in July 1916 as part of the effort against Germany in World War I. In late 1916, Russian forces brutally suppressed the widespread armed resistance to the taking of land and conscription of Central Asians. Thousands of Kazakhs were killed, and thousands of others fled to China and Mongolia.

In the Soviet Union

In 1917 a group of secular nationalists called the Alash Orda (Horde of Alash), named for a legendary founder of the Kazakh people, attempted to set up an independent national government. This state lasted less than two years (1918-1920) before surrendering to the Bolshevik authorities, who then sought to preserve Russian control under a new political system. The Kyrgyz Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic was set up in 1920 and was renamed the Kazakh Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic in 1925 when the Kazakhs were differentiated officially from the Kyrgyz. (The Russian Empire recognized the ethnic difference between the two groups; it called them both "Kyrgyz" to avoid confusion between the terms "Kazakh" and "Cossack ((both names originating from "horse rider")).")

In 1925 the autonomous republic's original capital, Orenburg, was reincorporated into Russian territory. Almaty (called Alma-Ata during the Soviet period), a provincial city in the far southeast, became the new capital. In 1936 the territory was made a full Soviet republic, the Kazakh SSR, also called Kazakhstan. With an area of 2,717,300 km² (1,063,200 square miles), the Kazakh SSR was the second largest constituent republic of the Soviet Union. From 1929 to 1934, during the period when Soviet leader Joseph V. Stalin was trying to collectivize agriculture, Kazakhstan endured repeated famines because peasants had slaughtered their livestock in protest against Soviet agricultural policy. In that period, at least 1.5 million Kazakhs and 80 percent of the republic's livestock died. Thousands more Kazakhs tried to escape to China, although most starved in the attempt.

Many European Soviet citizens and much of Russia's industry were relocated to Kazakhstan during World War II, when Nazi armies threatened to capture all the European industrial centers of the Soviet Union. Groups of Crimean Tatars, Germans, and Muslims from the North Caucasus region were deported to Kazakhstan during the war because it was feared that they would collaborate with the enemy. Most Poles (about one million) from Eastern Poland invaded by USSR in 1939 were deported to Kazakhstan, and half of them died there. Local people became famous for sharing their meager food with the starving strangers. Many more non-Kazakhs arrived in the years 1953-1965, during the so-called Virgin Lands campaign of Soviet premier Nikita S. Khrushchev (in office 1956-1964). Under that program, huge tracts of Kazakh grazing land were put to the plow for the cultivation of wheat and other cereal grains. Still more settlers came in the late 1960s and 1970s, when the government paid handsome bonuses to workers participating in a program to relocate Soviet industry close to the extensive coal, gas, and oil deposits of Central Asia. One consequence of the decimation of the nomadic Kazakh population and the in-migration of non-Kazakhs was that by the 1970s Kazakhstan was the only Soviet republic in which the eponymous nationality was a minority in its own republic.

Reform and Nationalist Conflict

The 1980s brought glimmers of political independence, as well as conflict, as the central government's hold progressively weakened. In this period, Kazakhstan was ruled by a succession of three Communist Party officials; the third of those men, Nursultan Nazarbayev, continued as president of the Republic of Kazakhstan when independence was proclaimed in 1991.

In December 1986, Soviet premier Mikhail S. Gorbachev (in office 1985-1991) forced the resignation of Dinmukhamed Kunayev, an ethnic Kazakh who had led the republic as first secretary of the CPK from 1959 to 1962, and again starting in 1964. During 1985, Kunayev had been under official attack for cronyism, mismanagement, and malfeasance; thus, his departure was not a surprise. However, his replacement, Gennadiy Kolbin, an ethnic Russian with no previous ties to Kazakhstan, was unexpected. Kolbin was a typical administrator of the early Gorbachev era - enthusiastic about economic and administrative reforms but hardly mindful of their consequences or viability.

The announcement of Kolbin's appointment provoked spontaneous street demonstrations by Kazakhs, to which Soviet authorities responded with force. Demonstrators, many of them students, rioted. Two days of disorder followed, and at least 200 people died or were summarily executed soon after. Some accounts estimate casualties at more than 1,000.

Kunayev had been ousted largely because the economy was failing. Although Kazakhstan had the third-largest gross domestic product in the Soviet Union, trailing only Russia and Ukraine, by 1987 labor productivity had decreased 12%, and per capita income had fallen by 24 percent of the national norm. By that time, Kazakhstan was underproducing steel at an annual rate of more than a million tons. Agricultural output also was dropping precipitously.

While Kolbin was promoting a series of unrealistic, Moscow-directed campaigns of social reform, expressions of Kazakh nationalism were prompting Gorbachev to address some of the non-Russians' complaints about cultural self-determination. One consequence was a new tolerance of bilingualism in the non-Russian regions. Kolbin made a strong commitment to promoting the local language and in 1987 suggested that Kazakh become the republic's official language. However, none of his initiatives went beyond empty public-relations ploys. In fact, the campaign in favor of bilingualism was transformed into a campaign to improve the teaching of Russian.

While attempting to conciliate the Kazakh population with promises, Kolbin also conducted a wholesale purge of pro-Kunayev members of the CPK, replacing hundreds of republic-level and local officials. Although officially "nationality-blind," Kolbin's policies seemed to be directed mostly against Kazakhs. The downfall of Kolbin, however, was the continued deterioration of the republic's economy during his tenure. Agricultural output had fallen so low by 1989 that Kolbin proposed to fulfill meat quotas by slaughtering the millions of wild ducks that migrate through Kazakhstan. The republic's industrial sector had begun to recover slightly in 1989, but credit for this progress was given largely to Nursultan Nazarbayev, an ethnic Kazakh who had become chairman of Kazakhstan's Council of Ministers in 1984.

As nationalist protests became more violent across the Soviet Union in 1989, Gorbachev began calling for the creation of popularly elected legislatures and for the loosening of central political controls to make such elections possible. These measures made it increasingly plain in Kazakhstan that Kolbin and his associates soon would be replaced by a new generation of Kazakh leaders.

Rather than reinvigorate the Soviet people to meet national tasks, Gorbachev's encouragement of voluntary local organizations only stimulated the formation of informal political groups, many of which had overtly nationalist agendas. For the Kazakhs, such agendas were presented forcefully on national television at the first Congress of People's Deputies, which was convened in Moscow in June 1989. By that time, Kolbin was already scheduled for rotation back to Moscow, but his departure probably was hastened by riots in June 1989 in Novyy Uzen, an impoverished western Kazakhstan town that produced natural gas. That rioting lasted nearly a week and claimed at least four lives.

The Rise of Nazarbayev

In June 1989, Kolbin was replaced by Nazarbayev, a politician trained as a metallurgist and engineer. Nazarbayev had become involved in party work in 1979, when he became a protégé of reform members of the CPSU. Having taken a major role in the attacks on Kunayev, Nazarbayev may have expected to replace him in 1986. When he was passed over, Nazarbayev submitted to Kolbin's authority and used his party position to support Gorbachev's new line, attributing economic stagnation in the Soviet republics to past subordination of local interests to the mandates of Moscow.

Soon proving himself a skilled negotiator, Nazarbayev bridged the gap between the republic's Kazakhs and Russians at a time of increasing nationalism while also managing to remain personally loyal to the Gorbachev reform program. Nazarbayev's firm support of the major Gorbachev positions in turn helped him gain national and, after 1990, even international visibility. Many reports indicate that Gorbachev was planning to name Nazarbayev as his deputy in the new union planned to succeed the Soviet Union.

Even as he supported Gorbachev during the last two years of the Soviet Union, Nazarbayev fought Moscow to increase his republic's income from the resources it had long been supplying to the center. Although his appointment as party first secretary had originated in Moscow, Nazarbayev realized that for his administration to succeed under the new conditions of that time, he had to cultivate a popular mandate within the republic. This difficult task meant finding a way to make Kazakhstan more Kazakh without alienating the republic's large and economically significant Russian and European populations. Following the example of other Soviet republics, Nazarbayev sponsored legislation that made Kazakh the official language and permitted examination of the negative role of collectivization and other Soviet policies on the republic's history. Nazarbayev also permitted a widened role for religion, which encouraged a resurgence of Islam. In late 1989, although he did not have the legal power to do so, Nazarbayev created an independent religious administration for Kazakhstan, severing relations with the Muslim Board of Central Asia, the Soviet-approved oversight body in Tashkent.

In March 1990, elections were held for a new legislature in the republic's first multiple-candidate contests since 1925. The winners represented overwhelmingly the republic's existing elite, who were loyal to Nazarbayev and to the Communist Party apparatus. The legislature also was disproportionately ethnic Kazakh: 54.2% to the Russians' 28.8%.

Sovereignty and Independence

In June 1990, Moscow declared formally the sovereignty of the central government over Kazakhstan, forcing Kazakhstan to elaborate its own statement of sovereignty. This exchange greatly exacerbated tensions between the republic's two largest ethnic groups, who at that point were numerically about equal. Beginning in mid-August 1990, Kazakh and Russian nationalists began to demonstrate frequently around Kazakhstan's parliament building, attempting to influence the final statement of sovereignty being developed within. The statement was adopted in October 1990.

In keeping with practices in other republics at that time, the parliament had named Nazarbayev its chairman, and then, soon afterward, it had converted the chairmanship to the presidency of the republic. In contrast to the presidents of the other republics, especially those in the independence-minded Baltic states, Nazarbayev remained strongly committed to the perpetuation of the Soviet Union throughout the spring and summer of 1991. He took this position largely because he considered the republics too interdependent economically to survive separation. At the same time, however, Nazarbayev fought hard to secure republic control of Kazakhstan's enormous mineral wealth and industrial potential. This objective became particularly important after 1990, when it was learned that Gorbachev had negotiated an agreement with Chevron, a United States oil company, to develop Kazakhstan's Tengiz oil fields. Gorbachev did not consult Nazarbayev until talks were nearly complete. At Nazarbayev's insistence, Moscow surrendered control of the republic's mineral resources in June 1991. Gorbachev's authority crumbled rapidly throughout 1991. Nazarbayev, however, continued to support him, persistently urging other republic leaders to sign the revised Union Treaty, which Gorbachev had put forward in a last attempt to hold the Soviet Union together.

Because of the coup attempted by Moscow hard-liners against the Gorbachev government in August 1991, the Union Treaty never was signed. Ambivalent about the removal of Gorbachev, Nazarbayev did not condemn the coup attempt until its second day. However, once the incompetence of the plotters became clear, Nazarbayev threw his weight solidly behind Gorbachev and continuation of some form of union, largely because of his conviction that independence would be economic suicide.

At the same time, however, Nazarbayev pragmatically began preparing his republic for much greater freedom, if not for actual independence. He appointed professional economists and managers to high posts, and he began to seek the advice of foreign development and business experts. The outlawing of the CPK, which followed the attempted coup, also permitted Nazarbayev to take virtually complete control of the republic's economy, more than 90% of which had been under the partial or complete direction of the central Soviet government until late 1991. Nazarbayev solidified his position by winning an uncontested election for president in December 1991.

A week after the election, Nazarbayev became the president of an independent state when the leaders of Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus signed documents dissolving the Soviet Union. Nazarbayev quickly convened a meeting of the leaders of the five Central Asian states, thus effectively raising the specter of a "Turkic" confederation of former republics as a counterweight to the "Slavic" states (Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus) in whatever federation might succeed the Soviet Union. This move persuaded the three Slavic presidents to include Kazakhstan among the signatories to a recast document of dissolution. Thus, the capital of Kazakhstan lent its name to the Alma-Ata Declaration, in which eleven of the fifteen Soviet republics announced the expansion of the thirteen-day-old CIS. On December 16, 1991, just five days before that declaration, Kazakhstan had become the last of the republics to proclaim its independence.

Moving forward

The Soviet Union's spaceport, now known as the Baikonur Cosmodrome was located in this republic at Tyuratam, with the secret town of Leninsk being constructed to accommodate the workers at the Cosmodrome.

Current issues include: resolving ethnic differences; speeding up market reforms; establishing stable relations with Russia, China, and other foreign powers; and developing and expanding the country's abundant energy resources.