Mongol Empire

|

|

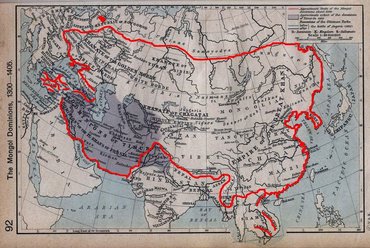

The Mongol Empire (1206–1368) was the largest contiguous land empire in world history (with its only rival in total extent being the British Empire and possibly the Soviet Union). Founded by Genghis Khan in 1206, it encompassed the majority of the territories from southeast Asia to eastern Europe. During its existance, the Mongol Empire facilitated great cultural exchange and trade between the East, West, and the Middle East during the time between 13th century and 14th century.

The Mongol Empire was also tremendously destructive. R. J. Rummel estimates that 30 million people were killed during the reign of the Mongol Empire, and the population of China fell by half in fifty years of Mongol rule. The rapid expansion of the Mongol Empire was facilitated by brutal responses to resistance, along with the military skill, organization, and discipline of Genghis Khan and his successors.

Tbe Mongol Empire had a lasting impact, unifying large regions, some of which (such as eastern and western Russia and the western parts of China) remain unified today. While much of the Mongol culture was eventually assimilated into local populations, and the descendants of the empire adopted Islam, the empire had a lasting impact, both in historical and more direct terms -- recent genetic tests appear to indicate that one out of every 200 males in Eurasia may be descended from Genghis Khan [need a reference here].

At the time of Genghis Khan's death in 1227, the empire was divided among his four sons with his third son as the nominal supreme Khan, but by the 1350s, the khanates were in a state of fracture and had lost the organization of Genghis Khan. Eventually the separate khanates drifted away from each other (e.g. Golden Horde, Yuan Dynasty).

| Contents |

Formation

Genghis Khan, through political manipulation and military might, united the Mongol tribes under his rule by 1206. He quickly came into conflict with the Jin empire of the Jurchen and the Western Xia in northern China. Under the provocation of the Khwarezmid Empire, he moved into Central Asia as well, devastating Transoxiana and eastern Persia, then raiding into southern Russia and the Caucasus. While engaged in a final war against the Western Xia, Genghis fell ill and died. Before dying, Genghis Khan divided his empire among his sons and immediate family, but as custom made clear, it remained the joint property of the entire imperial family who, along with the Mongol aristocracy, constituted the ruling class.

Major Events in the Early Mongol Empire

- By 1206 Temuchin dominated Mongolia and received the title Genghis Khan, thought to mean Oceanic Ruler or Firm, Resolute Ruler

- 1207, the Mongols began operations against the Western Xia, which comprised much of northwestern China and parts of Tibet. This campaign lasted until 1210 with the Western Xia ruler submitting to Genghis Khan. During this period, the Uighurs also submitted peacefully to the Mongols and became valued administrators throughout the empire.

- 1211, after a great quriltai or meeting, Genghis Khan led his armies against the Jin Dynasty that ruled northern China.

- 1219–1222 While the campaign above was still in progress, the Mongols waged a war in central Asia and destroyed the Khwarazmian Empire, killing around 1.5 million of its inhabitants. One notable feature was that the campaign was launched from several directions.

- 1226, Invasion of the Western Xia, being the second battle with the Western Xia.

Organization

Military setup

The Mongol military organization was simple, but effective. The organization was based on an old tradition of the steppe, which was like todays decimal system: the army was built upon a squad of ten, called an "arban"; ten "arbans" constituted a company of a hundred, called a "jaghun". Ten "jaghuns" made a regiment of a thousand – "mingghan". Ten "mingghans" would then constitute a regiment of ten thousand ("tumen"), which is the modern equivalent of a division.

The army's discipline distinguished Mongol soldiers from their peers. The forces under the command of the Mongol Empire were generally tailored for mobility and speed. To ensure mobility, Mongol soldiers were relatively lightly armored compared to many of the armies they faced. In addition, soldiers of the Mongol army functioned independently of supply lines, considerably speeding up army movement. Discipline was inculcated in traditional hunts or nerge as reported by Juvayni.

All military campaigns were preceded by careful planning, reconnaissance and gathering of sensitive information relating to the enemy territories and forces. The success, organization and mobility of the Mongol armies let them fight on several fronts at once. All males who were aged from 15 to 60 and were capable of undergoing rigorous training were eligible for conscription into the army.

Unlike other mobile fighters such as the Huns or the Vikings, the Mongols were very comfortable in the art of the siege. They were very careful to recruit artisans from the cities they plundered, and along with a group of experienced Chinese engineers, they were expert in building the trebuchet and other siege machines. These were mostly built on the spot using nearby trees.

Another advantage of the Mongols was their ability to traverse large distances even in debilitatingly cold winters; in particular, frozen rivers led them like highways to large urban conurbations on their banks. In addition to siege engineering, the Mongols were also adept at river-work, crossing the river Sajo in spring flood conditions with thirty thousand cavalry during one night during the battle of Mohi (April, 1241), defeating the Hungarian king Bela IV. Similarly, in the attack against the Khwarezmshah, a flotilla of barges were used to prevent escape on the river.

Law and governance

The Mongol Empire was governed by a code of law devised by Genghis, called Yassa, meaning "order" or "decree." A particular canon of this code was that the nobility shared much of the same hardship as the common man. It also made for very stiff penalties, e.g. the death penalty was decreed if the mounted soldier following another did not pick up something dropped from the mount in front. At the same time, meritocracy prevailed, and Subutai, one of the most succesful Mongol generals, started life as a blacksmith's son. On the whole, the tight discipline made the Mongol Empire extremely safe and well-run; European travelers were amazed by the organization and strict discipline of the people within the Mongol Empire.

Under Yassa, chiefs and generals were selected based on merit, religious tolerance was guaranteed, and thievery and vandalization of civilian property was strictly forbidden. According to legend, a woman carrying a sack of gold could travel safely from one end of the Empire to another.

The empire was governed by a non-democratic parliamentary-style central administration called Kurultai in which the Mongol chiefs met with the Great Khan to discuss domestic and foreign policies.

Genghis also demonstrated a rather liberal and tolerant attitude to the beliefs of others, and never persecuted people on religious grounds. This proved to be good military strategy, as when he was at war with Sultan Muhammad of Khwarezm, other Islamic leaders did not join the fight against Genghis - it was instead seen as a non-holy war between two individuals.

Throughout the empire, trade routes and an extensive postal system ("yam") were created. Many merchants, messengers and travelers from China, the Middle East and Europe used the system. Genghis Khan also created a national seal, encouraged the use of a written alphabet in Mongolia, and exempted teachers, lawyers, and artists from taxes, although taxes were heavy on all other subjects of the empire.

At the same time, any resistance to Mongol rule was met with massive collective punishment. Cities were destroyed and their inhabitants slaughtered if they defied Mongol orders.

Trade networks

Mongols prized their commercial and trade relationships with neighboring economies and this policy they continued during the process of their conquests and during the expansion of their empire. All merchants and ambassadors, having proper documentation and authorization, traveling through their realms were protected. This greatly increased overland trade.

During the thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries, European merchants, numbering hundreds, perhaps thousands, made their way from Europe to the distant land of China Marco Polo is only one of the best known of these. Well-traveled and relatively well-maintained roads linked lands from the Mediterranean basin to China. The Mongol Empire had negligible influence on seaborne trade, which was much larger, both in value and volume than the overland trade that passed through the territories under the control of the Mongol empire.

After Genghis Khan

The empire's expansion continued for a generation or more after Genghis's death in 1227 — indeed, it was under Genghis's successor Ögedei Khan that the speed of expansion reached its peak. Mongol armies pushed into Persia, finished off the Xia and the remnants of the Khwarezmids, and came into conflict with the Song Dynasty of China, starting a war that would last until 1279 and that would conclude with the Mongols' successful conquest of China.

Then, in the late 1230s, the Mongols under Batu Khan invaded Russia, reducing most of its principalities to vassalage, and pressed on into Eastern Europe. In 1241 the Mongols may have been ready to invade western Europe as well, having defeated the last Polish-German and Hungarian armies at the Battle of Legnica and the Battle of Mohi. However, at this point, news of Ögedei's death led to first the partial suspension of the invasion and then to its effective conclusion as Batu's attention switched to the election of the next Great Khan.

During the 1250s, Genghis's grandson Hulegu Khan, operating from the Mongol base in Persia, destroyed the Abbasid Caliphate in Baghdad and destroyed the cult of the Assassins, moving into Palestine towards Egypt. The Great Khan Möngke having died, however, he hastened to return for the election, and the force that remained in Palestine was destroyed by the Mamluks under Baibars in 1261 at Ayn Jalut.

Disintegration

When Genghis Khan died, a major potential weakness of the system he had set up manifested itself. It took many months to summon the kurultai, as many of its most important members were leading military campaigns thousands of miles from the Mongol heartland. And then it took months more for the kurultai to come to the decision that had been almost inevitable from the start — that Genghis's choice as successor, his third son Ögedei, should indeed become Great Khan. Ögedei was a rather passive ruler and personally self-indulgent, but he was intelligent, charming and a good decision-maker whose authority was respected throughout his reign by apparently stronger-willed relatives and generals whom he had inherited from Genghis.

On Ögedei's death in 1241, however, the system started falling apart. Pending a kurultai to elect Ögedei's successor, his widow Toregene Khatun assumed power and proceeded to ensure the election of her son Guyuk by the kurultai. Batu, though, was unwilling to accept Guyuk as Great Khan but without the power in the kurultai to procure his own election. Therefore, while moving no further west, he simultaneously insisted that the situation in Europe was too precarious for him to come east and that he could not accept the result of any kurultai held in his absence. The resulting stalemate lasted four years — in 1246 Batu eventually agreed to send a representative to the kurultai but never acknowledged the resulting election of Guyuk as Great Khan.

Guyuk died in 1248, only two years after his election, on his way west apparently to force Batu to acknowledge his authority, and his widow Oghul Ghaymish assumed power pending the meeting of the kurultai. But she could not keep the power. Batu again remained in the west but this time gave his support to his and Guyuk's cousin, Möngke, who was duly elected Great Khan in 1251.

It was Möngke Khan who unwittingly provided his brother Kublai with a chance to become Khan in 1260. Möngke assigned Kublai to a province in North China. Kublai expanded the Mongol empire and became a favorite of Möngke. Kublai's conquest of China is estimated by Holworth, based on census figures, to have killed over 18 million people. [1] (http://www.hawaii.edu/powerkills/DBG.CHAP3.HTM)

Later, though, when Kublai began to adopt many Chinese laws and customers, his brother was persuaded by his advisors that Kublai was becoming too Chinese and would become treasonous. Möngke kept a closer watch on Kublai from then on until his death campaigning in the west. After his older brother's death, Kublai placed himself in the running for a new khan against his younger brother, and, although his younger brother won one election, Kublai won the second, and Kublai became Kublai Khan.

He proved to be a strong warrior, but his critics still accused him of being too closely tied to Chinese culture. When he moved his headquarters to Peking, there was an uprising in the old capital that he barely staunched. He focused mostly on foreign alliances, and opened trade routes. He dined with a large court every day, and met with many ambassadors, foreign merchants, and even offered to convert to Christianity if this religion was proved to be correct by 100 priests.

By the reign of Kublai Khan, the empire was already in the process of splitting into a number of smaller khanates. After Kublai died in 1294, his heirs failed to maintain the Pax Mongolica and the Silk Road closed.

Inter-family rivalry (compounded by the complicated politics of succession, which twice paralyzed military operations as far off as Hungary and the borders of Egypt, crippling their chances of success) and the tendencies of some of the khans to drink themselves to death fairly young (causing the aforementioned succession crises) hastened the disintegration of the empire.

Another factor which contributed to the disintegration was the decline of morale when the capital was moved from Karakorum to modern day Beijing by Kublai Khan, because Kublai Khan associated more with Chinese culture. Kublai concentrated on the war with the Song, assuming the mantle of ruler of China, while the more western khanates gradually drifted away.

The four descendant empires were the Mongol-founded Yuan Dynasty in China, the Chagatai Khanate, the Golden Horde that controlled Central Asia and Russia, and the Ilkhans who ruled Persia from 1256 to 1353. Of the latter, their ruler Ilkhan Ghazan was converted to Islam in 1295 and actively supported the expansion of this religion in his empire.

Silk Road

The Mongol expansion throughout the Asian continent from around 1215 to 1360 helped bring political stability and re-establish the Silk Road vis-à-vis Karakorum. With rare exceptions such as Marco Polo or Christian ambassadors such as William of Rubruck, few Europeanstraveled the entire length of the silk road. Instead traders moved products much like a bucket brigade, with luxury goods being traded from one middleman to another, from China to the West, and resulting in extravagant prices for the trade goods.

The disintegration of the Mongol Empire led to the collapse of the Silk Road's political unity. Also falling victim were the cultural and economic aspects of its unity. Turkmeni tribes seized the western end of the Silk Road from the decaying Byzantine Empire, and sowed the seeds of a Turkic culture that would later crystalize into the Ottoman Empire under the Sunni faith. Turkmen and Mongol military bands in Iran, after some years of chaos were united under the Saffavid tribe, under whom the modern Iranian nation took shape under the Shiite faith. Meanwhile Mongol princes in Central Asia were content with Sunni orthodoxy with decentralized princedoms of the Chagatay, Timurid and Uzbek houses. In the Kypchak-Tatar zone, Mongol khanates all but crumbled under the assaults of the Black Death and the rising power of Moscovite. In the east end, the Chinese Ming Dynasty overthrew the Mongol yoke and pursued a policy of economic isolationism. Yet another force, the Kalmyk-Oyrats pushed out of the Baikal area in central Siberia, but failed to deliver much impact beyond Turkestan. Some Kalmyk tribes did manage to migrate into the Volga-North Caucasus region, but their impact was limited.

After the Mongol Empire, the great political powers along the Silk Road became economically and culturally separated. Accompanying the crystallization of regional states was the decline of nomad power, partly due to the devastation of the Black Death and partly due to the encroachment of sedentary civilizations equipped with gunpowder.

Ironically, as a footnote, the effect of gun power and early modernity on Europe was the integration of territorial states and increasing mercantilism. Whereas along the Silk Road, it was quite the opposite: failure to maintain the level of integration of the Mongol Empire and decline in trade, partly due to European maritime trade. The Silk Road stopped serving as a shipping route for silk around 1400.

Legacy

The Mongol Empire was the largest contiguous empire in human history. The 12th and 13th century, when the empire came to power, is often called the "Age of the Mongols". The Mongol armies during that time were extremely well organized. The death toll (by battle, massacre, flooding, and famine) of the Mongol wars of conquest is placed at about 40 million according to some sources (http://users.erols.com/mwhite28/warstat0.htm#Mongol). M

Non-military achievements of the Mongol Empire include the introduction of a writing system, based on the Uighur script, and the same is still used in Inner Mongolia. The Empire caused the unification of all the tribes of Mongolia, which made possible the emergence of a Mongol nation and culture. Modern Mongolians are proud of the empire and the sense of identity that it gave to them.

Some of the long-term implications of the Mongol Empire include:

- The Mongol empire has always been given credit for expanding the frontiers of China and imparting political unity to China, a unity which China never lost.

- The Mongol empire (Western) was also responsible for unifying much of the Central Asian republics that formed part of the erstwhile USSR. Today, in a number of Central Asian nations, Tamerlane and other Mongol figures are viewed important symbols of national identity rather than mere "feudal oppressors".

- Russia rose to prominence during this time because Russian rulers were accorded the status of tax collectors for Mongols. In fact, the Russian ruler Ivan the terrible overthrew the Mongols to form the empire that eventually became the USSR. The historical results of this are still simmering in Chechnya, Siberia, and other disparate parts of Russia

- Persia became Iran with almost the same boundaries as the modern Iran. The Persian language got ascendancy over Arabic in Iran.

- The language Chagatai, widely spoken among a group of Turks, is named after a son of Genghis Khan, was once widely spoken, with a literature, but was ruthlessly eliminated in Russia.

- Some historians attribute the origins of the Emirate of Osman, the nucleus of the laterOttoman Empire, to the Mongol empire.

- Europes knowledge of the known world was immensely expanded by the information brought back by ambassadors and merchants. When Columbus sailed in 1492, his mission was to reach Cathay, the land of the Genghis Khan. Some research studies indicate that the Black Death, which devastated Europe in the late 1340s, may have reached from China to Europe along the trade routes of the Mongol Empire.

- The Mongol Empire set an example of religious tolerance. A number of principles by which the empire was ruled continue to be emulated in modern times, and form the basis of several principles of modern democratic states.

See also

References

- Howorth, Henry H. HISTORY OF THE MONGOLS FROM THE 9TH TO THE 19TH CENTURY: PART I: THE MONGOLS PROPER AND THE KALMUKS. New York: Burt Frankin, 1965 (reprint of London edition, 1876).

External links

- Genghis Khan and the Mongols (http://www.fsmitha.com/h3/h11mon.htm)

- The Mongol Empire (http://www.allempires.com/empires/mongol/mongol1.htm)

- Mongols (http://www.accd.edu/sac/history/keller/Mongols/intro.html)

- Genghis Khan Biography (http://www.leader-values.com/Content/detail.asp?ContentDetailID=799)de:Geschichte der Mongolen

he:האימפריה המונגולית ja:モンゴル帝国 fi:Mongolivaltakunta es:Imperio Mongol ko:몽고 제국 nl:Mongoolse Rijk zh:蒙古帝国