Hernando de Soto (explorer)

|

|

Hernando de Soto (born 1496 or 1500, Jerez de los Caballeros, Extremadura, and died 21 May 1542, probably on a branch of the Mississippi river near present-day Lake City, Arkansas) was a Spanish navigator and conquistador; de Soto participated in the conquest of Panama at the side of Pedro Arias d'Avila (Pedrarias), Nicaragua and was with Francisco Pizarro in Peru. Later, de Soto led the largest expedition of the 16th and 17th century through the southeast and midwest of today's USA.

| Contents |

Travels and Career

In 1514, de Soto accompanied Pedrarias to the Spanish colonies, landing in Panama. His only possessions then were a shield and his sword. In 1516, he became commander of an equestrian unit and went with Francisco Fernandez de Cordoba on his discovery and colonization voyage through Nicaragua and Honduras. De Soto gained fame as an excellent horseman, fighter, and tactician, but was known for extreme brutality and ruthlessness when dealing with natives. In a conflict for supremacy in Nicaragua, de Soto fought for Davila against Gil Dᶩda Gonzales; Gonzales, an ex-officer of Davila, had tried to break away from him. De Soto denunciated the treason and defeated Gonzales's army. As a result, Davilas leadership was secured and de Soto gained his favour. In 1528 de Soto led his own expedition along the coast of Yucatan, hoping to find a direct connection by sea between the Atlantic and the Pacific Ocean.

DeSoto gained much of his wealth in the trafficking of slaves and came to own large areas of land in the Spanish colonies, as well as gold mines and trade ships. Apparently though, his aim was to achieve a similar success as [[HernᮠCort鳝] in the defeat of the Aztec empire.

To that end, he accompanied Francisco Pizarro as Pizarro's direct representative on his venture against Peru, and explored the country. De Soto discovered the city of Cajas, where his men raped the sacred virgins in the Temple of the Sun. With a group of fifty men, he discovered a road to the Tahuantinsuyu capital Cuzco, and became the first European to talk to the Inca ruler Atahualpa when he preceded Pizarro to Cajamarca on their invasion march. After Atahualpa had been arrested, DeSoto often visited him in jail, and a friendship between the two men emerged.

When the Andes were to be redistributed among the conquistadors, de Soto became furious and disunited with Pizarro. He returned to Spain in 1536, taking with him approximately 100,000 golden pesos — his share of the conquest of Tahuantinsuyu. At this time, De Soto was famous for being the hero of the battle of Cuzco. He settled in Sevilla, where he married, in 1537, In鳠de Bobadilla, the daughter of Davila. She came from one of the most respectable families of Castilia, with good connections to the Spanish court. This period was the apex of de Soto's reputation and wealth.

De Soto, having seen the legendary resources in Peru and read a report written by Cabeza de Vaca, suspected a similar wealth in Florida. Vaca was one out of four survivors of the disastrous attempt of Pᮦilo de Narv to conquer Florida. (In Narv's ill-fated expedition, only four men survived out of 400.) De Soto saw his chance to second the famous conquests of Pizarro and Cortez. He was declared the governor of Cuba y adelante de La Florida (meaning: all lands north of Mexico) by Emperor Charles V. De Soto sold all of his goods and equipped an expedition into the unexplored lands. His mission was to conquer, to settle, and to "pacify" the unknown territories.

Expedition to Florida 1538-1542

1539 – Landing in Florida

After a short stop in the Canary Islands, de Soto first headed towards Cuba. The city of Havana had, just shortly before his arrival, been plundered and burned down by French pirates. De Soto had his men rebuild the city, while he continued gathering resources, horses, and men for his expedition to Florida.In May 1539, he landed with approximately 600 to 700 men, twenty-four priests, nine ships, and 220 horses on the western coast of Florida, in Bradenton (south of Tampa). He named the place Espiritu Santo after the Holy Ghost. De Soto's aim was to colonize the area, preferably from the center of a city like Cuzco or Mexico City. Therefore, he brought several tons of equipment, tools, arms, cannons, dogs, and pigs. The dogs — mostly Irish wolfhounds — became notorious weapons and instruments of punishment for the army. In addition to the sailors, the ships brought priests, blacksmiths, craftsmen, engineers, farmers, and merchants. Few of them had ever traveled outside of Spain, or even their home villages.

Around the same time, the Mexican viceroy, Antonio de Mendez, sent an expedition under Francisco Vᳱuez de Coronado into the territories explored by DeVaca to search for what came to be known as the Seven Cities of Cibola, a gold-rich land of legend. De Soto feared for his claims on La Florida. During the whole of his travels, de Soto felt pressure to be the first to discover the legendary treasures and appropriate settling grounds.

The exact course of de Soto's expedition is subject to discussions and controversy among historians and local politicians. The primary historical sources are journals left by the Spaniards, including de Soto's own secretary. Aside from the usual precaution that has to be applied to such sources, particular problems have to be considered in regards to de Soto's expedition. The Spaniards were ignorant of the lay of the land. Their communication with the natives often had to pass through a chain of interpreters, so that names and toponyms may have been written down incorrectly. Additionally, many leaders and contacts had their own interests in leading the expedition in the wrong directions. Archeological reconstructions and the oral history of the natives have only lately been considered. However, this bears the handicap that most historical places have been overbuilt and more than 450 years of history have passed between the incidence and its narration.

The most widespread version, which is also taught in U.S. schools, recurs in a report of the U.S. Congress, under the lead management of anthropologist John R. Swanton, from the year 1939. While the first part of the expedition's course, until the battle at Mabila, is only disputed in details, the meandering route of the later voyage remains largely unclear. The Spaniards were disoriented and had almost no equipment left which could have served as indications for the archeologists. The commonly assumed De Soto Trail runs in a west-northwest direction across the US states Mississippi, Arkansas and Oklahoma until Texas. Other opinions argue for a northern route across Kentucky and Indiana to the Great Lakes.

1539 – Exploration of Florida

Beginning at the Espiritu Santo, de Soto explored Florida and large parts of the southern United States. Already in Florida, his misfortune began. Instead of being full of gold, the country was full of swamps and mosquitos, and was extremely hot and humid. Also, the indios he brought with him angered the native tribes.

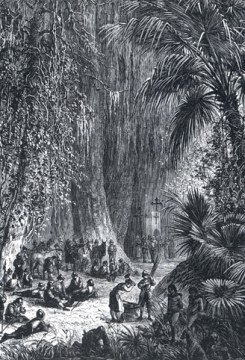

The natives had had bad experiences with the earlier expedition of Pᮦilo de Narv. De Soto's troops were no less brutal. They captured Indians to use as workers and guides, raped women, and looted villages in their search for food for their men and horses. Most often, de Soto let the villages burn down and set up a Christian cross on the sacred places of the Indians. In addition to slaves and guides, the Spaniards often captured the tribes' chieftains in order to gain safe passage.

The most important helper of the troops was Juan Ortiz, who came to Florida in search of the Narvaez expedition and was captured by the Uzica, a Calusa tribe. Ucita's (Chief Hirrihigua) daughter is the real "Pocahontas" who begged for Ortiz's life, as her father had ordered Ortiz to be roasted alive. He survived captivity and torture, and joined, at the first opportunity, the new de Soto Spanish expedition. Ortiz knew the countryside and also helped as an interpreter. As a lead guide for the de Soto expedition, Ortiz established a unique method for guiding the expedition and communicating with various tribal dialects. The "Paracoxi" guides were recruited from each tribe along the route. A chain of communication was established whereby a guide who had lived in close proximity to another tribal area was able to pass his information and language on to a guide from a neighboring area. Because Ortiz refused to dress and conduct himself as a hidalgo Spaniard, his motives and council to de Soto were held in suspicion by other officers. But Don Hernando remained loyal to Ortiz, thus allowing him freedom to dress and live among his tribal Paracoxi friends.

Another important guide was the seventeen-year-old boy Perico, or Pedro, from modern-day Georgia, who spoke several of the local tribes' languages and could communicate with Ortiz. Perico was engaged as a guide in 1540 and treated better than the rest of the slaves, due to his value to the Spaniards.

The first winter encampment of the expedition took place in Anheica, the capital of the Apalachee, close to Lake Tallahas. The site is also near "Bahia de Caballos" where the members of the Narvaez expedition were forced to eat valued horseflesh for survival. This is the only place on the entire route where the archeologists agree that de Soto's expedition effectively has not been.

1540 – To the North, The Battle of Mauvila

The expedition ventured along the eastern Appalachian Mountains and left a trail of destruction. Sometimes the members of the expedition traded the pigs they brought along to obtain food, sometimes they tried to get what they needed by force. They crossed modern-day Georgia, South Carolina, and North Carolina.

Having heard of the famous gold treasure of the Cofitachequi, and accompanied by their enemies, the Ocute, the expedition continued on to the Carolinas. During weeks of marches, through hunger and thirst, they realised that neither Perico nor the Ocute knew their way through the territories of the Cofitachequi. Nonetheless, in the middle of May, the expedition discovered the capital of the tribe, situated at the site of today's Columbia, South Carolina.

The Spaniards were received in a relatively friendly manner — especially considering that they looted and pillaged several villages of the Cofitachequi on their way. The Cofitachequi princess seemingly turned over her tribe's sacred burial sites, pearls, and anything the Spaniards valued to Don Hernando. However, the Spaniards demanded to see the city's gold at once. Upon closer examination, the "gold" emerged as simple copper. The Spaniards raided the city's burial temples, looting ancient treasures. They found some pearls and weapons in the city, took the young and charismatic female leader as a hostage, and ventured on in their search for wealth, across the Carolinas, Georgia, and Alabama.

On their further erratic travels, they were led by wrong promises of giant gold reserves in the east. In northern Alabama, they stumbled upon the city of Mauvila (or Mabila). The Choctaw tribe, under chieftain Tascalusa, ambushed them on the central place of the strongly-fortified city. The Spaniards managed to fight their way out, then attacked the city over and over again. In a battle of nine hours, twenty Spaniards died, almost all were wounded, and twenty more died during the next few days. All Choctaw warriors in the area — between 2,000 and 6,000 in number — died fighting, in the fires, by executions, or by suicide. Mauvila was burned down.

Even though the Spaniards won the battle, they lost most of their possessions and forty horses. They were wounded, sickened, and almost without equipment in an unknown territory, surrounded by enemies. With the battle of Mauvila, the natives' respect for the expedition also decreased. The Spaniards were attacked more and more often by guerillas and in the open.

While his men had lost their hopes and now only wanted to reach the coast to meet ships that were expected to come from Cuba, de Soto still strived for new discoveries. The expedition wintered in Chicasa in modern-day Mississippi.

1541 – To the West, Demoralised

The expedition returned upcountry to the north, where they met the Chickasaw tribe. De Soto demanded 200 men as porters from the Chickasaw. They denied his claim and attacked the Spanish camp during the night. The Spaniards lost about forty men and the remainder of their equipment. According to participating chronists, the expedition could have been destroyed. Luckily for the expedition, the Chickasaw let them go, intimidated by their own success.

On May 8, 1541, de Soto's troops reached the Mississippi river. It is unclear whether he, as it is claimed, was the first European to see the great river. However, he is the first to document this fact in official reports.

De Soto was less interested in this discovery though, recognizing it, first of all, as an obstacle to his mission. He and 400 men had to cross the broad river, which was constantly patrolled by hostile natives. After about one month, and the construction of several floats, they finally crossed the Mississippi and continued their travels westwards through modern-day Arkansas, Oklahoma, and Texas. They wintered in Autiamique, on the Arkansas river.

1542 – de Soto's Death

After a harsh winter, the Spanish expedition decamped and moved on more and more erratically. By then, the last Spaniard who was remotely familiar with the area, Juan Ortiz, had died. Eventually, the Spaniards returned to the Mississippi.On the banks of this river, de Soto died on June 25, 1542 of a fever. Since he had propagated among the natives the myth that Christians were immortal, his men had to conceal his death. They hid his corpse in blankets weighted with sand and sank it in the river. While Spain and Portugal could have been crossed by a trained wanderer in less than one month, de Soto's expedition roamed through La Florida for three years without finding the expected treasures or a place to begin with their colonisation. His men aborted the expedition.

After one more year of wandering, they finally reached Spanish territory in Mexico, via the Mississippi River and the Gulf of Mexico. On their return journey, they were heavily attacked by the Natchez and other tribes, who had united against the Spaniards. Out of the initial 700 participants, 311 found their way home.

After Effects

De Soto's excursion to Florida was, from his view and the view of his men, a deadly disaster. They acquired neither gold nor prosperity and founded no colonies. The reputation of the expedition, at the time, was more that of Don Quixote than that of [[HernᮠCort鳝]. Nonetheless, it had several consequences.

On one hand, the expedition left its traces in the travelled areas themselves. Some of the horses that escaped or were stolen formed the cadre of the North American mustangs. De Soto was instrumental in forming the aggressive and hostile relationship between natives and Europeans. More devastating than the gory battles, however, were the diseases carried by the members of the expedition. Several areas the expedition crossed were basically depopulated. Many of the natives fled the cities struck by the illnesses towards the surrounding hills and swamps. The social structures of the population at the time were fundamentally changed.

On the other hand, the records of the expedition contributed in large part to geographic, biological, and ethnologic knowledge in Europe. The de Soto expedition's descriptions of the North American natives are the earliest known source of knowledge on the societies in the southeastern North Americas. They are, de facto, the only European description of North American native habits before the natives encountered other Europeans. De Soto's men were, at the same time, the first and the last Europeans to experience the prime of the Mississippian culture.

De Soto's expedition also led the Spanish crown to reconsider Spain's attitude towards its colonies north of Mexico. De jure, he created a claim on large parts of the North Americas for the Spaniards, with their missions concentrated mainly on the state of Florida and the pacific coast.

De Soto County in Mississippi and Hernando County in Florida are named after Hernando de Soto. The place of his disembarkation, Espiritu Santo, is located in Hernando County. De Soto County is where he allegedly died. Since 1948, the De Soto National Memorial has existed near the city of St. Petersburg, Florida. Several other cities and a car model are named after him.

Literature

- Garcilaso de la Vega, Historia del adelantado H. de S. (Madr. 1723).

- Young, Gloria A. and Michael Hoffmann: The Expedition of Hernando de Soto West of the Mississippi, 1541-1543: Proceedings of the de Soto Symposia, 1988 and 1990 University of Arkansas Press 1999 ISBN 1557285802

- Duncan, David Ewing: Hernando de Soto: A Savage Quest in the Americas; University of Oklahoma Press 1997. ISBN 0806129778

- Milanich, Jeralt T., Charles R. Ewen and John H. Hann: Hernando de Soto Among the Apalachee: The Archaeology of the First Winter Encampment; University Press of Florida, 1998. ISBN 081301557X

- Clayton, Lawrence A. Clayton, Vernon J. Knight and Edward C. Moore (Editor): The de Soto Chronicles: The Expedition of Hernando de Soto to North America in 1539-1543; University of Alabama Press 1996. ISBN 0817308245

- Swanton, John: Final Report of the United States: De Soto Expedition Commission; Prentice Hall & IBD 1987.

External links

- De Soto Memorial in Florida (http://www.nps.gov/deso/)

- Map of the expedition route (http://www.cr.nps.gov/seac/beneathweb/ch10/m13.jpg)

- De Sotos youth (http://www.floridahistory.com/spain-in-america.html)

- Report on the research to reconstruct the route of the expedition (http://muweb.millersville.edu/~columbus/data/ark/COUGHLN1.ARK)

- Detailed justification of an alternate expedition route to the Great Lakes (http://www.floridahistory.com/inset33.html)

- Map of the alternate expedition route (http://www.floridahistory.com/inset78m.html)