Geology of the Zion and Kolob canyons area

|

|

Kolob_Canyons_from_end_of_Kolob_Canyons_Road.jpg

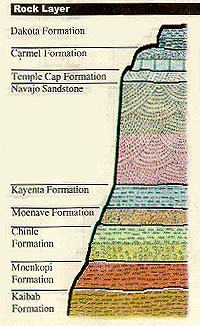

The geology of the Zion and Kolob canyons area includes nine known exposed formations, all visible in Zion National Park in the state of Utah in the United States, and representing about 150 million years of mostly Mesozoic-aged sedimentation. Part of the Grand Staircase, the formations exposed in the Zion and Kolob area were deposited in several different environments that range from warm shallow seas, streams, and lakes to large deserts and dry near shore environments. Subsequent uplift of the Colorado Plateau exposed these sediments to erosion by streams that preferentially cut through weaker rocks and jointed formations. Much later, lava flows and cinder cones covered parts of the Zion area.

Zion National Park includes an elevated plateau that consists of sedimentary formations that dip very gently to the east. This means that the oldest strata are exposed along the Virgin River in the Zion Canyon part of the park, and the youngest are exposed in the Kolob Canyons section. The plateau is bounded on the east by the Sevier Fault Zone, and on the west by the Hurricane Fault Zone. Weathering and erosion along north-trending faults and fractures influence the pattern of landscape features associated with canyons in this stream-incised plateau region.

The Grand Staircase and basement rocks

The oldest exposed formation in the park is the youngest exposed formation in the Grand Canyon—the approximately 240-million-year-old Kaibab limestone (see geology of the Grand Canyon area). Bryce Canyon to the northeast continues where the Zion and Kolob area end by presenting Cenozoic-aged rocks (see geology of the Bryce Canyon area). In fact, the youngest formation seen in the Zion and Kolob area is the oldest exposed formation in Bryce Canyon—the Dakota Sandstone. Geologists call this super-sequence of rock units the Grand Staircase. Together, the formations of the Grand Staircase record nearly 2000 million years of the Earth's history in that part of North America.

275 million years ago in the Permian period the Zion and Kolob area was a relatively flat basin near sea level on the western margin of the supercontinent Pangaea. Sediments from surrounding mountains added weight to the basin, keeping it at relatively the same elevation (see isostasy). These sediments later lithified to form the Toroweap Formation, exposed in the Grand Canyon to the south but not in the Zion and Kolob area. This formation is not exposed in the park but does form its basement rock.

Deposition of sediments

Kaibab Formation (Upper Permian)

Hurricane_Cliffs1.jpeg

In later Permian time, the Toroweap basin (see above) was invaded by the warm-shallow edge of the vast Permian Ocean in what local geologists call the Kaibab Sea. Starting 260 million years ago, the yellowish-gray limestone of the fossil-rich Kaibab Formation was laid down as a limy ooze in a tropical climate. During this time, sponges, such as Actinocoelia meandrina, proliferated, only to be buried in lime mud and their internal silica needles (spicules) dissolved and recrystallized to form discontinuous layers of light-colored chert. In the park, this formation can be found in the Hurricane Cliffs above the Kolob Canyons Visitor Center and in an escarpment along Interstate 15 as it skirts the park. This is the same formation that forms the rims of the Grand Canyon to the south.

Moenkopi Formation (Lower Triassic)

Moenkopi_Formation.jpeg

In the Early Triassic (around 230 million years ago), the gypsum (from lagoon evaporites), mudstones, limestones, sandstones, shales, and siltstones of the Moenkopi Formation were laid down as many thousands of thin layers of sediment that reached a thickness of 1800 feet (550 m). The depositional environment was a near-shore one where the seashore alternated between advance (transgression) and retreat (regression). A prograding shoreline laid down muddy delta sediments which mixed with limy marine deposits. Outcrops of this brightly-colored red, brown, and pink banded formation can be seen in the Kolob Canyons section of the park and in buttes on either side of Utah State Route 9 between Rockville, Utah to the south and Virgin, Utah to the southwest of the park borders; progessively higher beds are exposed until the top of the formation is reached at the mouth of Parunweap Canyon (when traveling to the park on Route 9). The Moenkopi Formation is made of these members (from oldest to youngest):

- Virgin Limestone

- Shnabkaib Shale

- Upper Red Member

Chinle Formation (Upper Triassic)

Chinle_Formation_near_Springdale,_Utah.jpeg

Later, uplift exposed the Moenkopi Formation to erosion and shallow river deposition in the Late Triassic (this irregular contact zone can be seen between Rockville and Grafton, Utah). These sediments, along with volcanic ash deposited during this time as well, eventually became the mineral-rich Chinle Formation. Petrified wood and fossils of animals adapted to swampy environments (such as amphibians) have been found in this formation as well as relatively plentiful uranium ore (such as carnotite and other uranium-bearing minerals). The purple, pink, blue, white, yellow, gray, and red colored Chinle also contains shale, gypsum, limestone, sandstone, and quartz. Iron, manganese oxides and copper sulfide are often found filling gaps between pebbles. Purplish slopes made of the Chinle can be seen above the town of Rockville.

- The sand, gravel, and trees which made up these deposits were later strongly cemented by dissolved silica (probably from volcanic ash) in groundwater. Much of the bright coloration of the Chinle is due to soil formation during the Late Triassic. The lowermost member of the Chinle, the Shinarump, consists of a white, gray, and brown conglomerate made of coarse sandstone, and thin lenses of sandy mudstone, along with plentiful petrified wood. This member of the Chinle forms up to 200 foot (60 meter) thick prominent cliffs and its name comes from a Native American word meaning "wolf's rump" (a reference to the way this member erodes into gray, rounded hills).

- The 350 foot thick succession of volcanic ash-rich mudstone and sandstone that make up the Petrified Forest Member of the Chinle was deposited by rivers and lakes and surrounding floodplains. This is the same bright, multi-colored part of the Chinle that is exposed in Petrified Forest National Park and the Painted Desert. Petrified wood is, of course, also common in this member.

Moenave Formation (Lower Jurassic)

Moenave_Formation.jpeg

Early Jurassic uplift was accompanied by deposition of the Moenave Formation. The oldest beds of this formation belong to the reddish, slope-forming, thin beds of siltstone interbedded with mudstone and fine sandstone of its 140 to 375 foot (43 to 114 m) thick Dinosaur Canyon Member, which was probably laid down in streams, ponds and large lakes (evidence for this is in cross-bedding of the sediments and large numbers of fish fossils).

The upper member of the Moenave is the 75 to 150 foot (23 to 46 m) thick pale reddish-brown cliff-forming Springdale Sandstone. It was deposited in swifter, larger, and more voluminous streams than the older Dinosaur Canyon Member. Fossils of large sturgeon-like freshwater fish have been found in the beds of the Springdale Sandstone. The next member in the Moenave Formation is the thin-bedded Whitmore Point, which is made of mudstone and shale. The lower red cliffs seen from the Zion Human History Museum (until 2000 the Zion Canyon Visitor Center) are good, easy to see examples of this formation.

Kayenta Formation (Lower Jurassic)

Keyenta_Formation_in_Kolob_Canyons.jpeg

The sand and silt of the 200 to 600 foot (60 to 180 m) thick Kayenta Formation were laid down in Early Jurassic time in slower-moving intermittent streambeds in a semi-arid to tropical environment. Fossilized dinosaur footprints from sauropods have been found up the Left Fork of North Creek in this formation. Today the Kayenta is a red and mauve rocky slope former made of sandstone. shale, and siltstone that can be seen throughout Zion Canyon.

Navajo Formation (Lower to Mid Jurassic)

Navajo_Sandstone_seen_from_Hidden_Canyon_Trail.jpg

Approximately 190 to 136 million years ago in the Jurassic the Colorado Plateau area's climate increasingly became arid until 150,000 square miles (388,000 km²) of western North America became a huge desert, not unlike the modern Sahara. For perhaps 10 million years sometime around 175 million years ago sand dunes accumulated, reaching their greatest thickness in the Zion Canyon area; about 2200 feet (670 meters) at the Temple of Sinawava (photo) in Zion Canyon.

Most of the sand, made of 98% translucent, rounded grain quartz, was transported from coastal sand dunes to the west (what is now central Nevada). Today the Navajo Sandstone is a geographically widespread pale tan to red cliff and monolith former with very obvious sand dune cross-bedding patterns (photo). Typically the lower part of this remarkably homogeneous formation is reddish from iron oxide that percolated from the overlaying iron-rich Temple Cap formation (see below) while the upper part of the formation is a pale tan to nearly white color. The other component of the Navajo's weak cement matrix is calcium carbonate, but the resulting sandstone is friable (crumbles easily) and very porous. Cross-bedding is especially evident in the eastern part of the park where Jurassic wind directions changed often. The cross-hatched appearance of Checkerboard Mesa is a good example (photo).

Springs, such as Weeping Rock (photo), form in canyon walls made of the porous Navajo Sandstone when water hits and is channeled by the underlying non-porous Kayenta Formation. The Navajo is the most prominent formation exposed in Zion Canyon with the highest exposures being West Temple and Checkerboard Mesa. The monoliths in the sides of Zion Canyon are believed to have the tallest sandstone cliffs in the world.

Temple Cap Formation (Middle Jurassic)

Temple_Cap_Formation_atop_Navajo_Sandstone.jpg

In early Mid Jurassic time streams loaded with iron-oxide-rich mud flooded and partially leveled the sand dunes, creating the Temple Cap Formation. Thin beds of clay and silt mark the end of this formation as desert conditions briefly returned to the area. The most prominent outcrops of this formation make up the capstones of East Temple and West Temple in Zion Canyon. Rain dissolves some of the iron oxide and thus streaks Zion's cliffs red (the red streak seen on the Alter of Sacrifice is a famous example). Temple Cap iron oxide is also the source of the red-orange color of much the lower half of the Navajo Formation.

Carmel Formation (Middle Jurassic)

Carmel_Formation.jpg

A warm shallow sea started to advance into the region (transgress) 150 million years ago, finishing the job of flattening the sand dunes. Sedimentation of one to four foot (30 to 120 cm) thick beds of limy ooze with some sand and fossils occurred from Mid to Late Triassic time. Some calcareous silt peculated down into the buried sand dunes (carrying red oxides with it) and eventually cemented them into the sandstone of the Navajo Formation. The limy ooze above would later lithify into the 200 to 300 foot (60 to 90 m) thick hard and compact limestone of the Carmel Formation, which is notably exposed on Horse Ranch Mountain (photo) in the Kolob Canyons section of the park and near Mt. Carmel Junction east of the park.

A gap in the geologic record, an unconformity, follows the Carmel Limestone. Other formations totaling 2,800 feet (850 m) thick may have been deposited in the region during Late Jurassic and Early Cretaceous only to be uplifted and entirely removed by erosion.

Dakota Sandstone (Lower Cretaceous)

Dakota_Sandstone.jpg

A small remnant of the Dakota Sandstone is exposed on top of the 8766 foot (2672 m) high Horse Ranch Mountain (photo). This formation consists of a basal conglomerate and fossil-rich sandstone and was laid down during the Cretaceous period. This formation is the youngest one exposed in the Zion area but the oldest exposed in Bryce Canyon to the northeast . Deposition continued but the resulting formations were later uplifted and eroded away. For their story see geology of the Bryce Canyon area.

Tectonic activity and canyon formation

Regional forces

Compression from subduction off the west coast affected the area to some degree in later Mesozoic time by causing folding and thrust faulting. Evidence for this period can be seen in the Taylor Creek area in the Kolob section of the park.

Tensional forces forming the Basin and Range physiogeographic province to the west about 20 to 25 million years ago in Tertiary time created the two faults that bound the Markagunt Plateau (which underlies the park); the Savier Fault on the east and the Hurricane Fault on the west. Several normal faults also developed on the plateau.

Subsequent Colorado Plateau-related uplift and tilting of the Markagunt Plateau started 13 million years ago. This steepened the stream gradient of the ancestral Virgin River s (Zion Canyon section of the park), and Taylor and La Verkin creeks (Kolob Canyons section of the park), causing them to flow and downcut faster into the underlying Markagunt Plateau. Downcutting continues to be especially rapid after heavy rainstorms and winter runoff when the water contains large amounts of suspended and abrasive sand grains. Uplift and downcutting are so fast that slot canyons (very narrow river-cut features with vertical walls), such as the Zion Narrows, were eventually formed.

Volcanic activity

Basalt_flows_on_Hurricane_Cliffs.jpeg

Then from at least 1.4 million to 250,000 years ago in Pleistocene time basaltic lava flowed intermittently in the area, taking advantage of uplift-created weaknesses in the Earth's crust. Volcanic activity was concentrated along the Hurricane Fault west of the park that today parallels Interstate 15. Evidence of the oldest flows can be seen at Lava Point and rocks from the youngest are found at the lower end of Cave Valley. Some cinder cones were constructed much later in the southwest corner of the park.

Erosion

Rockslide_debris_in_Kolob_Canyons.jpeg

Stream downcutting continued along with canyon-forming processes such as mass wasting; sediment-rich and abrasive flood stage waters would undermine cliffs until vertical slabs of rock sheared away (this process continues to be especially efficient with the vertically-jointed Navajo Sandstone). All erosion types took advantage of pre-existing weaknesses in the rock such as rock type, amount of lithification, and the presence of cracks or joints in the rock. In all about 6000 feet (1800 m) of sediment were removed from atop the youngest exposed formation in the park (the Late Cretaceous-aged Dakota Sandstone).

At the Temple of Sinawava (itself at the head of Zion Canyon), the Virgin River has reached the softer Kayenta Formation below. Water erodes the shale, undermining the overlaying sandstone and causing it to collapse, widening the canyon. Geologists estimate that the Virgin River can cut another thousand feet (300 m) before it loses the ability to transport sediment to the Colorado River (U.S.) to the south. However, additional uplift will probably increase this figure.

Sentinal_Slide_in_Zion_Canyon.jpg

Landslides more than once dammed the Virgin River and created lakes where sediment accumulated. Every time the river eventually breached the slide and drained the lake, leaving a flat-bottomed valley. One notable stand was created about 4000 years ago when Sentinel Slide impounded the North Fork Virgin River, creating a lake that backed-up to Weeping Rock. The current site of Zion Lodge was under about 200 feet (~60 m) of water for around 700 years. Evidence of valley floors created by these lakes can be seen from Zion Canyon Scenic Drive south of Zion Lodge near Sentinel Slide.

Uplift and erosion are still occurring in the area, which is periodically rocked by mild to moderate earthquakes and flash floods. For example, in September 1992 a Richter Magnitude 5.8 earthquake caused a landslide visible just outside the park's entrance in Springdale, Utah and in 1998 a flash flood temporarily increased the Virgin River's flow rate from 200 to 4500 ft³/s (6 to 125 m³/s) .

See also

References

- Geology of National Parks: Fifth Edition, Ann G. Harris, Esther Tuttle, Sherwood D., Tuttle (Iowa, Kendall/Hunt Publishing; 1997) ISBN 0-7872-5353-7

- Secrets in The Grand Canyon, Zion and Bryce Canyon National Parks: Third Edition, Lorraine Salem Tufts (North Palm Beach, Florida; National Photographic Collections; 1998) ISBN 0-9620255-3-4

- Zion National Park: Sanctuary in the Desert, Nicky Leach (Mariposa, California; Sierra Press; 2000)

- Zion Map and Guide, "The Geology of Zion", National Park Service (Zion Natural History Association; Summer 2004)

- GORP — Zion National Park Geology (http://gorp.away.com/gorp/resource/us_national_park/ut/geo_zion.htm)

- National Park Service: Geology of Zion National Park [1] (http://www.nps.gov/zion/Geology.htm), [2] (http://www2.nature.nps.gov/geology/parks/zion/)

- National-park.com — Zion National Park Information (http://www.zion.national-park.com/info.htm)