Dot-com

|

|

Dot-com (also dotcom or redundantly dot.com) companies were the collection of start-up companies selling products or services using or somehow related to the Internet. They proliferated in the late 1990s dot-com boom, a speculative frenzy of investment in Internet and Internet-related technical stocks and enterprises. The name derives from the fact that many of them have the ".com" TLD suffix built into their company name.

| Contents |

Overview

In 1994 the Internet came to the general public's attention with the public advent of the Mosaic web browser and the nascent World Wide Web, and by 1996 it became obvious to most publicly-traded companies that a public web presence was no longer optional. Though at first people saw mainly the possibilities of free publishing and instant worldwide information, increasing familiarity with two-way communication over the "web" led to the possibility of direct web-based commerce (e-commerce) and instantaneous group communications worldwide. These concepts in turn intrigued many bright young, often underemployed people (see also Generation X), who realized that new business models would soon arise based on these possibilities, and wanted to be among the first to profit from these new models.

The sudden low price of reaching millions worldwide, and the possibility of selling to or hearing from those people at the same moment when they were reached, promised to overturn established business dogma in advertising, mail-order sales, customer relationship management, and many more areas. The web was a new killer app -- it could instantaneously bring together unrelated buyers and sellers, or advertisers and clients, in seamless and low-cost ways. Visionaries around the world grabbed friends, developed new business models that would not have been possible just 3 years before, and ran to their nearest venture capitalist.

The venture capitalists saw the fast rise in valuation of other such companies, and therefore moved faster and with less caution than usual, choosing to hedge the risk by starting many contenders and letting the market decide which would succeed. The low interest rates in 1998-1999 helped increase the startup capital amounts. Of course a proportion of the new entrepreneurs were truly talented at business administration, sales, and growth, but the majority were just people with ideas, and didn't manage the capital influx prudently. This majority formed the bulk of the "dot-com" companies.

A canonical "dot-com" company's business model relied on network effects to justify losing money to build market share, or even mind share, through giving their product away in the hope that they could eventually charge for it. (It's worth noting that Amazon.com and other successful survivors of the era proved this strategy sound in the long term, for a small few.) Many raised cash through public offerings on the stock exchanges, with stock often soaring to dizzying heights and making the initial controllers of the company wildly rich on paper. Dot-com companies were stereotyped as having extremely young and inexperienced managers wearing polo shirts with lavish offices including foosball, free food and soft drinks as well as Aeron chairs. Companies frequently held parties or expositions where free pens, t-shirts, stress balls, and other trinkets were given away emblazoned with the company's logo. The companies were also stereotyped as requiring extremely long work hours and high pressure.

An annual event started in 1995, the Webby Awards, working to recognize the best websites on the Internet. The event was typically an extravaganza held annually in San Francisco, California, near the heart of Silicon Valley. The ceremonies mirrored the flashy dot-com lifestyle with costumed guests, modern dancers, and faux-paparazzi to make guests feel important. The event peaked in 2001 with thousands in attendance. In 2002, it was a more somber event with only several hundred guests and little of the excess of the late 1990s. In 2003, the awards were reduced to a virtual event because many of the nominees couldn't fly to San Francisco due primarily to corporate belt-tightening and fear of losing their jobs. The 2005 edition was held in New York City.

Historically the dot-com boom can be seen as similar to a number of other technology inspired booms of the past including railroads in the 1840s, radio in the 1920s, transistor electronics in the 1950s, computer time-sharing in the 1960s, and home computers and biotechnology in the early 1980s.

Soaring stocks

A stock market bubble in financial markets is a term applied to a self-perpetuating rise or boom in the share prices of stocks of a particular industry. The term may be used with certainty only in retrospect when share prices have since crashed. A bubble occurs when speculators note the fast increase in value and decide to buy in anticipation of further rises, rather than because the shares are undervalued. Typically many companies thus become grossly overvalued. When the bubble "bursts", the share prices fall dramatically, and many companies go out of business.

The late 1990s boom in technology dot-com company stocks is a good example of a bubble, which burst in late 2000 and through 2001.

The dot-com model was inherently flawed: a vast number of companies all had the same business plan of monopolising their respective sectors through network effects, and it was clear that even if the plan was sound, there could only be at most one network-effects winner in each sector, and therefore that most companies with this business plan would fail. In fact, many sectors could not support even one company powered entirely by network effects.

In spite of this, vast fortunes were made by a few company founders whose companies were bought out at an early stage in the dot-com stock market bubble. These early successes made the bubble even more buoyant. An unprecedented amount of personal investing occurred during the boom. Stories of people quitting their jobs to become full-time day traders, while not representative, were common in the press.

Free spending

According to dot-com theory, an internet company's survival depended on expanding its customer base as rapidly as possible, even if it produced large annual losses. The phrase "Get large or get lost" was the wisdom of the day. At the height of the boom it was possible for a promising dot-com to make an initial public offering of its stock and raise a substantial amount of money even though it had never made a profit. But then the matter of burn rate came into play as capital was expended in operating a company with no profit and no viable business model.

Public awareness campaigns were one way that dot-coms sought to grow their customer base. These included television ads, print ads, and targeting of professional sporting events. The January 2000 Super Bowl featured seventeen dot-com companies (most memorably pets.com) that each paid over $2 million for a 30-second spot. In January 2001, just three dot-coms bought advertising spots. Iwon.com gave away $10 million to a lucky contestant on an April 2000 show that aired on CBS. Many dot-coms named themselves with onomatopeic nonsense words that they hoped would be memorable and not easily confused with a competitor.

Not surprisingly, the "growth over profits" mentality and the aura of "new economy" invincibility led some companies to engage in lavish internal spending, such as elaborate business facilities and luxury vacations for employees. Executives and employees who were paid with stock options in lieu of cash became instant millionaires when the company made its initial public offering; many invested their new wealth into yet more dot-coms.

Cities all over the United States sought to become the "next Silicon Valley" by building network-enabled office space to attract internet entrepreneurs. Communication providers, convinced that the future economy would require ubiquitous broadband access, went deeply into debt to improve their networks with high-speed equipment and fiber optic cables. A Worldcom executive famously remarked that internet traffic would double every hundred days for the foreseeable future. Companies that produced network equipment, such as Cisco Systems, profited greatly from these projects.

Similarly, in Europe the vast amounts of cash the mobile operators spent on 3G-licences in Germany, Italy and the United Kingdom for example led them into deep debt. The investments were blown out of proportion regardless of whether seen in the context of their current or projected future cash flow, but this fact was not publicly acknowledged until as late as 2001 and 2002. Due to the highly networked nature of the IT industry this quickly led into problems for small companies that were dependent on contracts from operators.

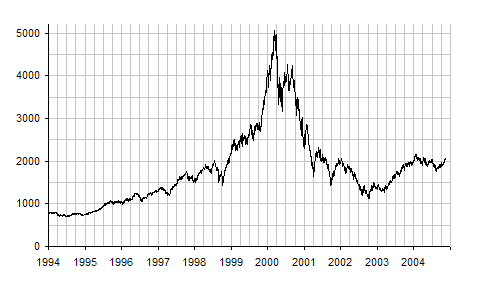

Thinning the herd

Over 1999 and early 2000, the Federal Reserve had increased interest rates six times, and the runaway economy was beginning to lose speed. The dot-com bubble burst, numerically, on March 10, 2000, when the technology heavy NASDAQ Composite index [1] (http://dynamic.nasdaq.com/dynamic/IndexChart.asp?symbol=IXIC&desc=NASDAQ+Composite&sec=nasdaq&site=nasdaq&months=84) peaked at 5048.62 (intra-day peak 5132.52), more than double its value just a year before. The NASDAQ fell slightly after that, but was attributed to correction; the actual reversal and subsequent bear market may have been triggered by the adverse findings of fact in the United States v. Microsoft case in the US. The findings, which declared Microsoft a monopoly, were widely expected in the weeks before their release on April 3.

Another reason may have been accelerated business spending in preparation for the Y2K switchover. Once New Year had passed without incident, businesses found themselves with all the equipment they needed for some time and business spending dried up. This correlates quite closely to the peak of U.S. stock markets. The Dow Jones peaked in January 2000 and the Nasdaq in March 2000. Hiring freezes, layoffs, and consolidations followed in several industries, especially in the dot-com.

By 2001, the bubble's deflation was running full speed. A majority of the dot-coms have now ceased trading, after having burnt through their venture capital, often without ever making a gross profit, thereby becoming dot-compost.

Aftermath

On January 11, 2001, America Online, a favorite of dot-com investors, acquired Time Warner, the world's largest media company. Within two years, boardroom disagreements drove out both of the CEOs who made the deal, and in October 2003 AOL Time Warner dropped "AOL" from its name. The acquisition thus became a symbol of the dot-coms' challenge to "old economy" companies and the old economy's ultimate survival. The revolutionary optimism of the boom faded, and analysts once again recognized the relevance of traditional business thinking.

Several communication companies, burdened with unredeemable debts from their expansion projects, sold their assets for cash or filed for bankruptcy. Worldcom, the largest of these, was found to have used accounting devices to overstate its profits by billions of dollars. The company's stock crashed when these irregularities were revealed, and within days it filed the largest corporate bankruptcy in US history. Other examples include NorthPoint Communications, Global Crossing, JDS Uniphase, XO Communications, Covad Communications. Demand for the new high-speed infrastructure never materialized, and it became dark fiber. Some analysts believe that there is so much dark fiber worldwide that only a small percentage of it will be "lit" in the decades to come.

One by one, dot-coms ran out of capital and were acquired or liquidated; the domain names were picked up by old-economy competitors or domain name squatters. Several companies were accused or convicted of fraud for misusing shareholders' money, and the Securities Exchange Commission fined top investment firms like Citigroup and Merrill Lynch millions of dollars for misleading investors. Various supporting industries, such as advertising and shipping, scaled back their operations as demand for their services fell. A few dot-com companies, such as Amazon.com and eBay, survived the turmoil and appear to have a good chance of long-term survival.

List of well-known dot-coms

Successful dot-coms

Failed dot-coms

- For more comprehensive listing of failed dot-coms, see here

See also

Terminology

- Bankruptcy

- Cube farm

- Digital Revolution

- E-commerce

- Irrational exuberance

- South Sea Bubble

- Spin-off

- Stock market bubble

- Tulipomania

- Techno-utopianism

Media

External links

- The Nasdaq Stock Market Crash (http://www.stock-market-crash.net/nasdaq.htm) - Learn about the spectacular rise and downfall of the Nasdaq.

- Looking back on the crash (http://www.guardian.co.uk/online/story/0,3605,1433697,00.html) - 5 years on, the Guardian sums up