Chariot

|

|

Chariot was the name of a WW2 naval weapon, the British manned torpedo.

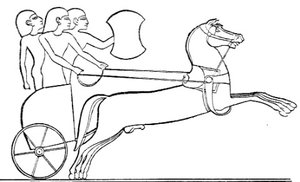

A chariot is a two-wheeled, horse-drawn vehicle. In Latin biga is a two-horse chariot, and quadriga is a four-horse chariot. It was used for battle during the Bronze and Iron Ages, and continued to be used for travel, processions and in games after it had been superseded militarily. Early forms may also have had four wheels, although these are not usually referred to as chariots. The critical invention that allowed the construction of light, horse-drawn chariots for use in battle was the spoked wheel. In these times, most horses could not support the weight of a man in battle; the original wild horse was a large pony in size. Chariots were effective in war only on fairly flat, open terrain. As horses were gradually bred to be larger and stronger, chariots gave way to cavalry. The earliest spoke-wheeled chariots date to ca. 2000 BC and their usage peaked around 1300 BC (see Battle of Kadesh). Chariot races continued to be popular in Constantinople until the 6th century.

In modern warfare, the tactical role of the chariot is played by the tank. In World War I, just before the introduction of the first tanks, motorcycles with machine-guns mounted on a sidecar constituted a mechanized version of the chariot, and the Russian tachanka briefly re-introduced horse-drawn chariots, armed with machine-guns.

| Contents |

Early forms

The earliest depiction of vehicles in the context of warfare is on the "battle standard" of Ur in southern Mesopotamia, ca. 2600 BC. The vehicles depicted are more properly called carts, still double-axled and pulled by tamed asses or onagers. Such heavy chariots may have been part of the baggage train rather than vehicles of battle in themselves. The Sumerians had also a lighter, two-wheeled type of chariot, pulled by four onagers, but still with solid wooden wheels. The spoked wheel did not appear in Mesopotamia until the mid 2nd millennium BC.

Indo-Iranians

Wheel_Iran.jpg

At least partially derived from the Yamna culture, a remarkable archaeological culture emerges around 2000 BC east of the Urals: The Sintashta-Petrovka culture built heavily fortified settlements, engaged in bronze metallurgy on a scale hitherto unprecedented and practiced complex burial rituals reminiscent of Aryan rituals known from the Rigveda. For the first time, the burials also include spoke-wheeled chariots, buried with two-horse chariot teams, the oldest of these dating to ca. 2000 BC, making them the oldest directly dated chariots (see also Kurgan). The Sintashta-Petrovka culture is accepted as the formative phase of the Andronovo culture, which over the next few centuries spread across the steppes from the Urals to the Tien Shan, likely corresponding to early Indo-Iranian cultures which eventually spread to Iran and India in the course of the 2nd millennium BC. The Indo-Aryan Mitanni would have spread the invention to the Middle East.

Chariots figure prominently in Indo-Iranian mythology. Chariots are also an important part of Hindu as well as of Persian mythology, with most of the gods in their pantheon portrayed as riding them. The Sanskrit word for a chariot is ratha, a collective to a Proto-Indo-European word for "wheel" that also resulted in Latin rota.

China

The earliest chariot burial site in China, discovered in 1933 at Hougang, Anyang of central China's Henan Province, dates to the rule of King Wu Ding of the Yin Dynasty (ca. 1200 BC). But chariots may have been known before, from as early as the Xia Dynasty (17th century BC) [1] (http://www.china.org.cn/english/MATERIAL/28792.htm). During the Shang dynasty, members of the royalty were buried with a complete household and servants, including a chariot, horses, and a charioteer. Shang chariot was often drawn by two horses, but four are occasionally found in burials. The crew consisted of an archer, a driver, and sometimes a third armed with a spear or dagger-axe. During the 8th to 5th centuries, Chiunese use of chariots reached its peak, they appeared in greater number, but infantry often defeated them in battle.

The chariot became obsolete during the Age of the Warring States; the main reasons were the invention of the crossbow and the adaptation of nomadic cavalry, which was more effective.

Ancient Near East

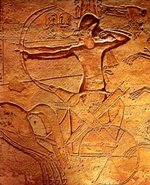

Egyptian

The chariot, together with the horse itself, was introduced to Egypt during the reign of the Hyksos dynasty in the 16th century BC. In the remains of Egyptian and Assyrian art there are numerous representations of chariots, from which it may be seen with what richness they were sometimes ornamented. The chariots of the Egyptians and Assyrians, with whom the bow was the principle arm of attack, were richly mounted with quivers full of arrows. The Egyptians invented the yoke saddle for their chariot horses in ca. 1500 BC. The best preserved examples of Egyptian chariots are the six specimens from the tomb of Tutankhamun.

Hittite

The Hittites were renowned charioteers. They developed a new chariot design, which had lighter wheels, with four spokes rather than eight, and which held three, instead of two warriors. Hittite prosperity largely depended on their control of trade routes and natural resources, specifically, metals. As the Hittites gained dominion over Mesopotamia, tensions flared between the neighboring Assyrians, Hurrians and Egyptians. Under Suppiluliuma I, the Hittites conquered Kadesh and eventually the whole of Syria. The Battle of Kadesh in 1299 BC is likely to have been the largest chariot battle ever fought, in which some five thousand chariots were involved.

Mycenaean

The Mycenaean Greeks made use of chariots in battle. Administrative records in Linear B script , mainly in Knossos, list chariots (wokha) and their spare parts and equipment, and distinguish between assembled and unassembled chariots. The Linear B ideogram for a chariot (B240, 𐃌) is an abstract drawing, showing two four-spoked wheels. The chariots fell out of use with the end of the Mycenaean civilization, and even in the Iliad, the heroes use the chariots merely as a means of transport, and dismount before engaging the enemy. Chariots were retained only for races in the public games, or for processions, without undergoing any alteration apparently, their form continuing to correspond with the description of Homer, though it was lighter in build, having to carry only the charioteer.

Chariots in the Bible

Chariots are frequently mentioned in the Old Testament, particularly by the prophets, as instruments of war or as symbols of power or glory. The first mention is in the story of Joseph (Genesis 50:9).

Examples (KJV):

- Song of Solomon 1:9 I have compared thee, O my love, to a company of horses in Pharaoh's chariots.

- Isaiah 2:7 Their land also is full of silver and gold, neither is there any end of their treasures; their land is also full of horses, neither is there any end of their chariots.

- Jeremiah 4:13 Behold, he shall come up as clouds, and his chariots shall be as a whirlwind: his horses are swifter than eagles. Woe unto us! for we are spoiled.

"Iron chariots" are mentioned in Joshua (17:16,18) and Judges (1:19,4:3,13) as weapons of the Canaanites. 1 Samuel 13:5 mentions (in exaggerated numbers) chariots of the Philistines, who are sometimes identified with the Sea Peoples or early Greeks.

Persian Empire

Darius_seal.jpg

The Persians may have been the first to yoke four horses (rather than two) to their chariots. They also developed a class of chariot having the wheels mounted with sharp, sickle-shaped blades, which crippled or pulverized whatever came in their way (scythed chariots). Cyrus the younger employed these chariots in large numbers. Herodotus mentions that the Indus satrapy supplied cavalry and chariots to Xerxes' army. The defeat of Darius III at the Battle of Gaugamela marked the end of the era of chariot warfare.

Celts and Etruscans

Etruscan_Chariot_530BC.jpg

The only Etruscan chariot found intact dates to ca. 530 BC. It is decorated with bronze plates reminiscent of the Gundestrup cauldron. Its wheels have nine spokes. it was part of a chariot burial.

The Celts were famous chariot-makers, and the English word car is believed to be derived, via Latin carrum, from Gaulish karros (English chariot itself is from 13th century French charriote, an augmentative of the same word). The iron rims for chariot wheels were probably a Celtic invention. Some 20 Iron Age chariot burials have been excavated in Britain, dating roughly from between 500 BC and 100 BC, virtually all of them in East Yorkshire, with the exception of one find of 2001 from Newbridge, 10km west of Edinburgh. Chariots play an important role in Irish mythology surrounding the hero Cu Chulainn.

According to Tacitus (Annals 14.35), Boudicca, a Celtic female chieftain who led the Iceni and a number of other Celtic tribes in a major uprising against the occupying Roman forces, addressed her troops, using a chariot to drive through the ranks before the Battle of Watling Street in 61 AD:

- Boudicca curru filias prae se vehens, ut quamque nationem accesserat, solitum quidem Britannis feminarum ductu bellare testabatur

- "Boudicea, with her daughters before her in a chariot, went up to tribe after tribe, protesting that it was indeed usual for Britons to fight under the leadership of women."

Classical Antiquity

Greece

The_Chariot_of_Zeus_-_Project_Gutenberg_eText_14994.png

The classical Greeks had a (still not very effective) cavalry, and the rocky terrain of the Greek mainland was unsuited for wheeled vehicles. In spite of this, the chariot retained a high status, memories of its era were handed down in epic poetry, and they were used for races at the Olympic and Panathenaic Games.

Delphi_charioteer_front_DSC06255.JPG

Greek chariots were made to be drawn by two horses attached to a central pole. If two additional horses were added, they were attached on each side of the main pair by a single bar or trace fastened to the front of the chariot, as may be seen on two prize vases in the British Museum from the Panathenaic Games at Athens, Greece, in which the driver is seated with his feet resting on a board hanging down in front close to the legs of his horses. The biga itself consists of a seat resting on the axle, with a rail at each side to protect the driver from the wheels. Greek chariots appear to have lacked any other attachment for the horses, which would have made turning difficult.

The body or basket of the chariot rested directly on the axle connecting the two wheels. There was no suspension, making this an uncomfortable form of transport. At the front and sides of the basket was a semicircular guard about 3 ft (1 m) high, to give some protection from enemy attack. At the back the basket was open, making it easy to mount and dismount. There was no seat, and generally only enough room for the driver and one passenger.

Greek_warrior_and_young_charioteer_-_Athens_pediment.jpg

The central pole was probably attached to the middle of the axle, though it appears to spring from the front of the basket. At the end of the pole was the yoke, which consisted of two small saddles fitting the necks of the horses, and fastened by broad bands round the chest. Besides this the harness of each horse consisted of a bridle and a pair of reins. The reins were mostly the same as those in use in the 19th century, and were made of leather and ornamented with studs of ivory or metal. The reins were passed through rings attached to the collar bands or yoke, and were long enough to be tied round the waist of the charioteer to allow him to defend himself.

The wheels and basket of the chariot were usually of wood, strengthened in places with bronze or iron. They had from four to eight spokes and tires of bronze or iron. Most other nations of this time had chariots of similar design to the Greeks, the chief differences being the mountings.

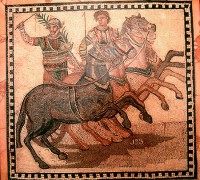

Roman Empire

The Romans probably borrowed chariot racing from the Etruscans, who would themselves had borrowed it either from the Celts or from the Greeks, but the Romans were also influenced directly by the Greeks especially after they conquered mainland Greece in 146 BC. In the Roman Empire, chariots were not used for warfare, but for processions and for chariot racing. The main centre of chariot racing was the Circus Maximus, situated in the valley between the Palatine and Aventine Hills in Rome. The track could hold 12 chariots, and the two sides of the track were separated by a raised median termed the spina. Chariot races continued to enjoy great popularity in Byzantine times, in the Hippodrome of Constantinople, even after the Olympic Games had been disbanded, until their decline after the Nika riots in the 6th century.

Russian Tachanka

The chariot was briefly revived during the Russian civil war of 1918–1920, when the "tachanka", a two- or four-wheeled cart with a machine-gun mounted on it, enjoyed a limited tactical success in the Red Army. Since the gun had to be pointed away from the horses, it operated by firing in a direction opposite or lateral to the direction in which the tachanka was moving. One man drove the horses, while another, or a team of two, operated the gun.

See Also

References

- Anthony, David W., 1995, Horse, wagon & chariot: Indo-European languages and archaeology, Antiquity Sept/1995

- "The Northern Frontier in Pre-Imperial China", Cambridge History of Ancient China (pp. 885-966) ch. 13, Nicolo Di Cosmo.

External links

es:Carro gl:Carro it:Carro he:מרכבה (רכב קרבי) pl:Rydwan pt:Carruagem