Axel Oxenstierna

|

|

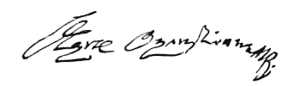

Count Axel Gustafsson Oxenstierna Template:Audio or Oxenstjerna (June 16, 1583 - August 28, 1654), Lord High Chancellor of Sweden, was born at Fånö in Uplandia, and received his education with his brothers at the universities of Rostock, Jena and Wittenberg. On returning home in 1603 he took up an appointment as kammarjunker to King Charles IX of Sweden. In 1606 he undertook his first diplomatic mission, to Mecklenburg, gained appointment to the Privy Council (Riksrådet) during his absence, and henceforth became one of the king's most trusted servants. In 1610 he travelled to Copenhagen with the aim of preventing war with Denmark, but unsuccessfully. This embassy has importance as marking the beginning of Oxenstierna's long diplomatic struggle with Sweden's traditional rival in the west, which he regarded as his country's most formidable enemy throughout his life.

| Contents |

Chancellor

Oxenstierna became a member of Gustavus Adolphus's council of regency (1611). As a major aristocrat, he would at first willingly have limited the royal power. An oligarchy guiding a limited monarchy ever remained his ideal government, but the genius of the young king demanded no fetters, so Oxenstierna remained content to serve as the colleague instead of the master of his sovereign. On the January 6, 1612 became Lord High Chancellor (Rikskansler) of the Privy Council. His controlling, organizing hand soon became apparent in every branch of the administration. For his services as first Swedish plenipotentiary at the Treaty of Knäred in 1613, he received rich rewards. During the frequent absences of Gustavus in Livonia and in Finland (1614 - 1616) Oxenstierna acted as his vice-regent, when he displayed manifold abilities and an all-embracing activity. In 1620 he headed the brilliant embassy dispatched to Berlin to arrange the nuptial contract between Gustavus and Maria Eleonora of Brandenburg. During the king's Russian and Polish wars he had the principal duty of supplying the armies and the fleets with everything necessary, including men and money. By this time he had become so indispensable that Gustavus, in 1622, bade Oxenstierna accompany him to Livonia and appointed him Governor-General and commandant of Riga. His services in Livonia gained him the reward of four castles and the whole bishopric of Wenden. Entrusted with the peace negotiations which led to the truce with Poland in 1623, he succeeded, by skilful diplomacy, in averting a threatened rupture with Denmark in 1624. On October 7, 1626 he became Governor-General of the Swedish possesions in the newly-acquired Province of Prussia. In 1629 he concluded the very advantageous Truce of Altmark with Poland-Lithuania. Previously to this, in September 1628, he arranged with Denmark a joint occupation of Stralsund, to prevent that important fortress from falling into the hands of the Imperialists.

Thirty Years' War

After the Battle of Breitenfeld on September 7, 1631 Oxenstierna received a summons to assist the king with his counsels and co-operation in Germany. During the king's absence in Franconia and Bavaria in 1632 he held the appointment of legatus in the Rhine lands, with plenipotentiary authority over all the German generals and princes in the Swedish service. Although he never fought a battle, he proved a born strategist, and frustrated all the efforts of the Spanish troops by his wise regulations. His military capacity showed strikingly with the skill with which he conducted large reinforcements to Gustavus through the heart of Germany in the summer of 1632. But only after the death of Gustavus Adolphus at Lützen in 1632 did Oxenstierna's true greatness came to light.

Power behind the throne

He inspired the despairing Protestants both in Germany and Sweden with fresh hopes. He reorganised the government both at home and abroad. He united the estates of the four upper circles into a fresh league against the common foe (1634), in spite of the envious and foolish opposition of Saxony. By the patent of January 12, 1633 he had already gained the appointment of legate plenipotentiary of Sweden in Germany, with absolute control over all the territory already won by the Swedish arms. No Swedish subject, either before or after, ever held such an unrestricted and far-reaching authority. Yet he proved more than equal to the extraordinary difficulties of the situation. To him both warriors and statesmen appealed invariably as their natural and infallible arbiter. Richelieu himself declared the Swedish Chancellor "an inexhaustible source of well-matured counsels". Less original but more sagacious than the king, he had a firmer grasp of the realities of the situation. Gustavus would not only have aggrandised Sweden, he would have transformed the German empire. Oxenstierna wisely abandoned these vaulting ambitions. His country's welfare remained his sole object. All his efforts directed themselves towards procuring for the Swedish crown adequate compensation for its sacrifices.

Simple to austere in his own tastes, he nevertheless recognised the political necessity of impressing his allies and confederates by an almost regal show of dignity; and at the abortive Congress of Frankfurt in March 1634, held for the purpose of uniting all the German Protestants, Oxenstierna appeared in a carriage drawn by six horses, with German princes attending him on foot. But from first to last his policy suffered from the slenderness of Sweden's material resources, a cardinal defect which all his craft and tact could not altogether conceal from the vigilance of her enemies. The success of his system postulated an uninterrupted series of triumphs, whereas a single reverse had the potential to overturn it. Thus the frightful disaster of Nördlingen on September 6, 1634 brought him, for an instant, to the verge of ruin, and compelled him, for the first time, so far to depart from his policy of independence as to solicit direct assistance from France. But, well aware that Richelieu needed the Swedish armies as much as he himself needed money, he refused at the Conference of Compiègne in 1635 to bind his hands in the future for the sake of some slight present relief. In 1636, however, he concluded a fresh subsidy-treaty with France at Wismar. The same year he returned to Sweden and took his seat in the Regency. His presence at home overawed all opposition, and such was the general confidence inspired by his superior wisdom that for the next nine years his voice, especially as regarded foreign affairs, remained omnipotent in the Privy Council.

Territorial gains for Sweden

He drew up beforehand the plan of the Torstensson War of 1643 - 1645, so brilliantly executed by Lennart Torstensson, and had the satisfaction of severely crippling Denmark by the Treaty of Brömsebro in 1645, which put Gotlandia, Ösel, Jemtia, Herdalia and for thirty years Hallandia in Swedish hands. His later years became embittered by the jealousy of the young Queen Christina of Sweden, who thwarted the old statesman in every direction. He always attributed the exiguity of Sweden's gains by the Peace of Westphalia following the conference in Osnabrück to Christina's undue interference, which merely gave Sweden Pomerania, Usedom, Wollin, Wismar and Bremen-Verden.

Oxenstierna at first opposed the abdication of Christina, because he feared mischief to Sweden from the unruly and adventurous disposition of her appointed successor, Charles Gustavus. The extraordinary consideration shown to him by the new king ultimately, however, reconciled him to the change. He died at Stockholm on August 28, 1654.

Quotation

"Behold, my son, with how little wisdom the world is governed" (in a letter to his offspring written in 1648). - Although attributed to Cardinal Richelieu as well, probably the most famous Swedish quotation in the Anglo-Saxon world.

See also

External links

- The Correspondence of Axel Oxenstierna (http://www.tei-c.org/Applications/apps-th03.html) - at Text Encoding Initiativede:Axel Oxenstierna