Art in Ancient Greece

|

|

Ac.charioteer.jpg

The art of ancient Greece has exercised an enormous influence on the culture of many countries from ancient times until the present, particularly in the areas of sculpture and architecture. In the West, the art of the Roman Empire was largely derived from Greek models. In the East, Alexander the Great's conquests initiated several centuries of exchange between Greek, Central Asian and Indian cultures, resulting in Greco-Buddhist art, with ramifications as far as Japan. Following the Renaissance in Europe, the humanist aesthetic and the high technical standards of Greek art inspired generations of European artists. Well into the 19th century, the classical tradition derived from Greece dominated the art of the western world.

| Contents |

Definitions

Art historians generally define Ancient Greek art as the art produced in the Greek-speaking world from about 1000 BC to about 100 BC. They generally exclude the art of the Mycenaean and Minoan civilisations, which flourished from about 1500 to about 1200 BC. Despite the fact that these were Greek-speaking cultures, there is little or no continuity between the art of these civilisations and later Greek art.

At the other end of the time-scale, art historians generally hold that Ancient Greek art as a distinct culture ended with the establishment of Roman rule over the Greek-speaking world in about 100 BC. After this date they argue, Greco-Roman art, though often impressive in scale, was largely derivative of earlier Greek models, and declined steadily in quality until the advent of Christianity brought the classical tradition to an end in the 5th century AD. (For the later periods, see Roman art and Byzantine art).

There is also a question relating to the word "art" in Ancient Greece. The Ancient Greek word τεχνη tekhnê, which is commonly translated as "art," more accurately means "skill" or "craftsmanship" (the English word "technique" derives from it). Greek painters and sculptors were craftsmen who learned their trade as apprentices, often being apprenticed to their fathers, and who were then hired by wealthy patrons. Although some became well-known and much admired, they were not in the same social position as poets or dramatists. It was not until the Hellenistic period (after about 320 BC) that "the artist" as a social category began to be recognised.

Styles/periods

The art of Ancient Greece is usually divided stylistically into three periods: the Archaic, the Classical and the Hellenistic.

As noted above, the Archaic age is usually dated from about 1000 BC, although in reality little is known about art in Greece during the preceding 200 years (traditionally known as the Dark Ages). The onset of the Persian Wars (480 BC to 448 BC) is usually taken as the dividing line between the Archaic and the Classical periods, and the reign of Alexander the Great (336 BC to 323 BC) is taken as separating the Classical from the Hellenistic periods.

In reality, there was no sharp transition from one period to another. Forms of art developed at different speeds in different parts of the Greek world, and as in any age some artists worked in more innovative styles than others. Strong local traditions, conservative in character, and the requirements of local cults, enable historians to locate the origins even of displaced works of art.

Surviving remnants and artifacts

Ac.artemisephesus.jpg

Ancient Greek art has survived most successfully in the forms of sculpture and architecture, as well as in such minor arts as coin design, pottery and gem engraving. From the Archaic period a great deal of painted pottery survives, but these remnants give a misleading impression of the range of Greek artistic expression. The Greeks, like most European cultures, regarded painting as the highest form of art. The painter Polygnotus of Thasos, who worked in the mid 5th century BC, was regarded by later Greeks in much the same way that people today regard Leonardo or Michelangelo, and his works were still being admired 600 years after his death. Today none of his works survives, not even as copies.

Greek painters worked mainly on wooden panels, and these perished rapidly after the 4th century AD, when they were no longer actively protected. Today nothing survives of Greek painting, except some examples of painted terra cotta and a few paintings on the walls of tombs, mostly in Macedonia and Italy. Of the masterpieces of Greek painting we have only a few copies from Roman times, and most are of inferior quality. Painting on pottery, of which a great deal survives, gives some sense of the aesthetics of Greek painting. The techniques involved, however, were very different from those used in large-format painting.

Even in the fields of sculpture and architecture, only a fragment of the total output of Greek artists survives. For the Christians of the 4th and 5th centuries, smashing a pagan idol was an act of piety. One of the sad facts of ancient history is that when marble is burned, lime is produced, and that was also the fate of the great bulk of Greek marble statuary during the Middle Ages. Likewise, the acute shortage of metal during the Middle Ages led to the majority of Greek bronze statues being melted down. Those statues which had survived did so primarily because they had been buried and forgotten, or as in the case of bronzes having been lost at sea.

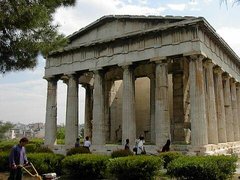

The great majority of Greek buildings have not survived to this day: either they had been pillaged in war, had been looted for building materials or had been destroyed in Greece’s many earthquakes. Only a handful of temples, such as the Parthenon and the Temple of Hephaestus in Athens, have been spared. Of the four Wonders of the World created by the Greeks — the Statue of Zeus at Olympia, the Temple of Artemis at Ephesus, the Colossus of Rhodes and Lighthouse of Alexandria) — nothing whatever survives.

As for the Archaic period of Greek art, painted pottery and sculpture are almost the only forms of art which have survived in any quantity. Painting was in its infancy during this period, and no examples of it have survived. Although coins were invented in the mid 7th century BC, they were not common in most of Greece until the 5th century.

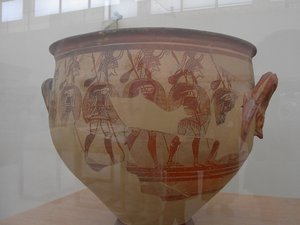

Pottery

The Ancient Greeks made pottery for everyday use, not for display; the trophies won at games, such as the Panathenaic amphorae (wine decanters), are the exception. Most surviving pottery consists of drinking vessels such as amphorae, kraters (bowls for mixing wine and water), hydria (water jars), libation bowls, jugs and cups. Painted funeral urns have also been found. Miniatures were also produced in large numbers, mainly for use as offerings at temples. In the Hellenistic period a wider range of pottery was produced, but most of it is of little artistic importance.

In earlier periods even quite small Greek cities produced pottery for their own locale. These varied widely in style and standards. Distinctive pottery that ranks as art was produced on some of the Aegean islands, in Crete, and in the wealthy Greek colonies of southern Italy and Sicily. By the later Archaic and early Classical period, however, the two great commercial powers, Corinth and Athens, came to dominate. Their pottery was exported all over the Greek world, driving out the local varieties. Pots from Corinth and Athens are found as far afield as Spain and Ukraine, and are so common in Italy that they were first collected in the 18th century as "Etruscan vases". Many of these pots are mass-produced products of low quality. In fact, by the 5th century BC, pottery had become an industry and pottery painting ceased to be an important art form.

The history of Ancient Greek pottery is divided stylistically into periods:

- the Protogeometric from about 1050 BC;

- the Geometric from about 900 BC;

- the Late Geometric or Archaic from about 750 BC;

- the Black Figure from the early 7th century BC;

- and the Red Figure from about 530 BC.

The range of colours which could be used on pots was restricted by the technology of firing: black, white, red, and yellow were the most common. In the three earlier periods, the pots were left their natural light colour, and were decorated with slip that turned black in the kiln.

The fully mature black-figure technique, with added red and white details and incising for outlines and details, originated in Corinth during the early 7th century BC and was introduced into Attica about a generation later; it flourished until the end of the 6th century BC. The red-figure technique, invented in about 530 BC, reversed this tradition, with the pots being painted black and the figures painted in red. Red-figure vases slowly replaced the black-figure style. Sometimes larger vessels were engraved as well as painted.

During the Protogeometric and Geometric periods, Greek pottery was decorated with abstract designs. In later periods, as the aesthetic shifted and the technical proficiency of potters improved, decorations took the form of human figures, usually representing the gods or the heroes of Greek history and mythology. Battle and hunting scenes were also popular, since they allowed the depiction of the horse, which the Greeks held in high esteem. In later periods erotic themes, both heterosexual and male homosexual, became common.

Greek pottery is frequently signed, sometimes by the potter or the master of the pottery, but only occasionally by the painter. Hundreds of painters are, however, identifiable by their artistic personalities: where their signatures haven't survived they are named for their subject choices, as "the Achilles Painter", by the potter they worked for, such as the Late Archaic "Kleophrades Painter", or even by their modern locations, such as the Late Archaic "Berlin Painter".

Sculpture

Ac.thebeskouros.jpg

Sculpture is by far the most important surviving form of Ancient Greek art, although only a small fragment of Greek sculptural output has survived. Greek sculpture, often in the form of Roman copies, was immensely influential during the Italian Renaissance, and remained the “classic” model for European sculpture until the advent of modernism in the late 19th century.

The Greeks decided at a very early period that the human form was the most important subject for artistic endeavour. Since they saw their gods as having human form, there was no distinction between the sacred and the secular in art — the human body was both secular and sacred. A male nude could just as easily be Apollo or Herakles or that year's current Olympic boxing champion. In the Archaic Period the most important sculptural form was the kouros (plural kouroi), the standing male nude (See for example Biton and Kleobis). The kore (plural korai), or standing female figure, was also common, but since Greek society did not permit the public display of female nudity until the 4th century BC, the kore is considered to be of less importance in the development of sculpture.

As with pottery, the Greeks did not produce sculpture merely for artistic display. Statues were commissioned either by aristocratic individuals or by the state, and used for public memorials, as offerings to temples, oracles and sanctuaries (as is frequently shown by inscriptions on the statues), or as markers for graves. In the Archaic period, statues were never intended to be representations of actual individuals. They were depictions of an ideal — beauty, piety, honour or sacrifice. They were always depictions of young men, ranging in age from adolescence to early maturity, even when placed on the graves of (presumably) elderly citizens. Kouroi were all stylistically similar. Gradations in the social importance of the person commissioning the statue were indicated by size rather than artistic innovation.

In the Classical period there was a revolution in Greek statuary, usually associated with the introduction of democracy and the end of the aristocratic culture associated with the kouroi. The Classical period saw changes in both the style and function of sculpture. Poses became more naturalistic (see the Charioteer of Delphi for an example of the transition to more naturalistic sculpture), and the technical skill of Greek sculptors in depicting the human form in a variety of poses greatly increased. From about 500 BC statues began to depict real people. The statues of Harmodius and Aristogeiton set up in Athens to mark the overthrow of the tyranny were said to be the first public monuments to actual people.

In this period statuary was put to wider uses. The great public buildings of the Classical era, such as the Parthenon in Athens, created the need for decorative statuary, particularly to fill the triangular fields of the pediments: a difficult aesthetic and technical challenge that did much to stimulate sculptural innovation. Unfortunately such sculptures survive only in fragments, the most famous of which are the Parthenon Marbles, now mostly in the British Museum.

Funeral statuary evolved during this period from the rigid and impersonal kouros of the Archaic period to the highly personal family groups of the Classical period. These monuments are commonly found in the suburbs of Athens, which in ancient times were cemeteries on the outskirts of the city. Although some of them depict "ideal" types — the mourning mother, the dutiful son — they increasingly depicted real people, typically showing the departed talking his dignified leave from his family. They are among the most intimate and affecting remains of the Ancient Greeks.

In the Classical period for the first time we know the names of individual sculptors. Phidias oversaw the design and building of the Parthenon. Praxiteles made the female nude respectable for the first time in the Late Classical period (mid 4th century): his Aphrodite of Cnidus, which survives in copies, was said by Pliny to be the greatest statue in the world.

The greatest works of the Classical period, the Statue of Zeus at Olympia and the Statue of Athena Parthenos (both executed by Phidias or under his direction), are lost, although smaller copies and good descriptions of both still exist. Their size and magnificence prompted emperors to seize them in the Byzantine period, and both were removed to Constantinople, where they were later destroyed in fires.

Missing image Ac.nike.jpg The Winged Victory of Samothrace (Hellenistic), Louvre, Paris |

The transition from the Classical to the Hellenistic period occurred during the 4th century. Following the conquests of Alexander the Great (336 BC to 323 BC), Greek culture spread across the known world as far as India. Thus it became more diverse and more influenced by the cultures of the peoples drawn into the Greek orbit. In the view of most art historians, it also declined in quality and originality; this, however, is a subjective judgement which artists and art-lovers of the time would not have shared. New centres of Greek culture, particularly in sculpture, developed in Alexandria, Antioch, Pergamum, and other cities. By the 2nd century the rising power of Rome had also absorbed much of the Greek tradition — and an increasing proportion of its products as well.

During this period sculpture became more and more naturalistic. Common people, women, children, animals and domestic scenes became acceptable subjects for sculpture, which was commissioned by wealthy families for the adornment of their homes and gardens. Realistic portraits of men and women of all ages were produced, and sculptors no longer felt obliged to depict people as ideals of beauty or physical perfection. At the same time, the new Hellenistic cities springing up all over Egypt, Syria, and Anatolia required statues depicting the gods and heroes of Greece for their temples and public places. This made sculpture, like pottery, an industry, with the consequent standardisation and some lowering of quality. For these reasons many more Hellenistic statues have survived than is the case with the Classical period.

Some of the best known Hellenistic sculptures are the Winged Victory of Samothrace (2nd or 1st century BC), the statue of Aphrodite from the island of Melos known as the Venus de Milo (mid 2nd century BC), the Dying Gaul (about 230 BC), and the monumental group Laocoön and his Sons (late 1st century BC). All these statues depict Classical themes, but their treatment is far more sensuous and emotional than the austere taste of the Classical period would have allowed or its technical skills permitted.

Hellenistic sculpture was also marked by an increase in scale, which culminated in the Colossus of Rhodes (late 3rd century), which was the same size as the Statue of Liberty. The combined effect of earthquakes and looting have destroyed this as well as other very large works of this period.

Architecture

Architecture (building executed to an aesthetically considered design) was extinct in Greece from the end of the Mycenaean period (about 1200 BC) until the 7th century, when urban life and prosperity recovered to a point where public building could be undertaken. But since most Greek buildings in the Archaic and Early Classical periods were made of wood or mud-brick, nothing remains of them except a few ground-plans, and there are almost no written sources on early architecture or descriptions of buildings. Most of our knowledge of Greek architecture comes from the few surviving buildings of the Classical, Hellenistic and Roman periods (since Roman architecture heavily copied Greek), and from late written sources such as Vitruvius (1st century AD). This means that there is a strong bias towards temples, the only buildings which survive in any number.

Architecture, like painting and sculpture, was not seen as an “art” in the modern sense for most the Ancient Greek period. The architect was a craftsman, employed by the state or a wealthy private client. There was no distinction between the architect and the building contractor. The architect designed the building, hired the labourers and craftsmen who built it, and was responsible for both its budget and its timely completion. He did not enjoy any of the lofty status accorded to modern architects of public buildings. Even the names of architects are not known before the 5th century. An architect like Iktinos, who designed the Parthenon, who would today be seen as a genius, was treated in his lifetime as no more than a very valuable master tradesman.

The standard format of Greek public buildings is well known from surviving examples such as the Parthenon, and even more so from Roman buildings built partly on the Greek model, such as the Pantheon in Rome. The building was usually either a cube or a rectangle made from limestone, of which Greece has an abundance, and which was cut into large blocks and dressed. Marble was an expensive building material in Greece: high quality marble came only from Mt Pentelus in Attica and from a few islands such as Paros, and its transportation in large blocks was difficult. It was used mainly for sculptural decoration, not structurally, except in the very grandest buildings of the Classical period such as the Parthenon.

Missing image Ac.tholos.jpg The Tholos at Delphi |

The basic cube or rectangle was usually flanked by colonnades (rows of columns) on either two or on all four sides. This is the format of the Parthenon. Alternatively, a cube-shaped building would have a columned portico (or pronaos in Greek) forming its entrance, as seen at the Pantheon. The Greeks understood the principles of the masonry arch but made little use of it, and did not put domes on their buildings— these refinements were left to the Romans. The Greeks roofed their buildings with timber beams covered with overlapping terra cotta (or occasionally marble) tiles.

The low pitch of Greek rooves produced a flat triangular shape at each end of the building, the pediment, which was usually filled with sculptural decoration. Along the sides of the building, between the tops of the columns and the roof, was a row of blocks now known as the entablature, whose outward-facing surfaces also provided a space for sculptures, known as friezes, which consisted of alternating metopes and triglyphs. No surviving Greek building preserves these sculptures intact, but they can be seen on some modern imitations of Greek buildings, such as the Greek National Academy building in Athens.

Missing image Ac.theatre.jpg The Theatre of Herodes Atticus, Athens |

The temple was the most common and best-known form of Greek public architecture. The temple did not serve the same function as a modern church. Some temples housed the altar of the god or goddess to whom it was dedicated, but many did not. Temples served as storage places for the treasury associated with the cult of the god in question, as the location of a statue of the god (though this was not an idol in a religious sense), and a place for devotees of the god to leave their offerings, such as dedicated statues. The inner building of the temple, the cella, thus served mainly as a strongroom and storeroom. It was usually lined by another row of columns.

Other common architectural forms used by the Greeks were the tholos, a circular structure of which the best example is at Delphi and which served religious purposes; the propylon or porch, which flanked the entrances to temple grounds and sanctuaries (the best known example is on the Acropolis of Athens); and the stoa, a long narrow hall with an open colonnade on one side, which was use to house rows of shops in the agoras (commercial centres) of Greek towns. A completely restored stoa, the Stoa of Attalus, can be seen in Athens.

Every Greek town of any size also had a palaestra or a gymnasium. These were essentially enclosed spaces, open to the sky and lined with shaded colonnades, used for athletic contests and exercise: they were the social centres for male citizens. Greek towns also needed at least one bouleuterion or council chamber, a large square building which served as both a meeting place for the town council (boule) and as a court house. Because the Greeks did not use arches or domes, they could not build large rooms with unsupported rooves: the bouleuterion thus had rows of internal columns to hold the roof up. No examples of these buildings survive.

Finally every Greek town had a theatre. These were used for both public meetings as well as dramatic performances. These performances originated as religious ceremonies; they went on to assume their Classical status as the highest form of Greek culture by the 6th century BC (see Greek theatre). The theatre was usually set in a hillside outside the town, and had rows of tiered seating set in a semi-circle around the central performance area, the orchestra. Behind the orchestra was a low building called the skene, which served as a store-room, a dressing-room, and also as a backdrop to the action taking place in the orchestra. A number of Greek theatres survive almost intact, the best known being at Epidaurus.

There were two main styles (or "orders") of Greek architecture, the Doric and the Ionic. These names were used by the Greeks themselves, and reflected their belief that the styles descended from the Dorian and Ionian Greeks of the Dark Ages, but this is unlikely to be true. The Doric style was used in mainland Greece and spread from there to the Greek colonies in Italy. The Ionic style was used in the cities of Ionia (now the west coast of Turkey) and some of the Aegean islands. The Doric style was more formal and austere, the Ionic more relaxed and decorative. The more ornate Corinthian style was a later development of the Ionic. These styles are best known through the three orders of column capitals, but there are differences in most points of design and decoration between the orders. See the separate article on Classical orders.

Most of the best known surviving Greek buildings, such as the Parthenon and the Temple of Hephaestus in Athens, are Doric. The Erechtheum, next to the Parthenon, however, is Ionic. The Ionic order became dominant in the Hellenistic period, since its more decorative style suited the aesthetic of the period better than the more restrained Doric. Some of the best surviving Hellenistic buildings, such as the Library of Celsus, can be seen in Turkey, at cities such as Ephesus and Pergamum. But in the greatest of Hellenistic cities, Alexandria in Egypt, almost nothing survives.

Coin design

- Main article: Greek coins

Coins were invented in Lydia in the 7th century, but they were first extensively used by the Greeks, and the Greeks set the canon of coin design which has been followed ever since. Coin design today still recognisably follows patterns descended from Ancient Greece. The Greeks did not see coin design as a major art form, but the durability and abundance of coins have made them one of the most important sources of knowledge about Greek aesthetics. Greek coins are, incidentally, the only art form from the ancient Greek world which can still be bought and owned by private collectors of modest means.

Greek designers began the practice of putting a profile portrait on the obverse of coins. This was initially a symbolic portrait of the patron god or goddess of the city issuing the coin: Athena for Athens, Apollo at Corinth, Demeter at Thebes and so on. Later, heads of heroes of Greek mythology were used. Greek cities in Italy such as Syracuse began to put the heads of real people on coins in the 4th century BC, and the Hellenistic kings of Egypt and Syria were soon putting their own heads on their coins. On the reverse of their coins the Greek cities often put a symbol of the city: an owl for Athens, a dolphin for Syracuse and so on. The placing of inscriptions on coins also began in Greek times. All these customs were later refined and developed by the Romans.