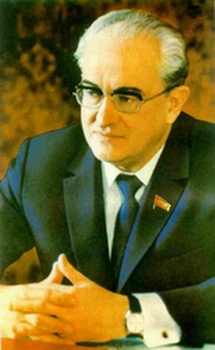

Yuri Andropov

|

|

| Name of Office (1): | General Secretary of the Soviet Communist Party |

| Term of Office: | 1982-1984 |

| Predecessor: | Leonid Brezhnev |

| Successor: | Konstantin Chernenko |

| Name of Office (2): | Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet |

| Term of Office: | 1982-1984 |

| Predecessor: | Leonid Brezhnev |

| Successor: | Konstantin Chernenko |

| Date of Birth: | June 15, 1914 |

| Place of Birth: | Nagutskoye, Imperial Russia |

| Date of Death: | February 9, 1984 |

| Place of Death: | Moscow, U.S.S.R |

| Profession: | Engineer |

| Political party: | Communist Party of the USSR |

Yuri Vladimirovich Andropov (Ю́рий Влади́мирович Андро́пов), (June 2 (O.S.) = June 15 (N.S.), 1914 – February 9, 1984) was a Soviet politician and General Secretary of the CPSU from November 12, 1982 until his death just sixteen months later.

| Contents |

Early life

Andropov was the son of a railway official and was probably born in Nagutskoye, Stavropol Guberniya, Imperial Russia. He was briefly educated at the Rybinsk Water Transport Technical College before he joined Komsomol in 1930. He graduated to the full party in 1939 and was first secretary of the Komsomol in the Soviet Karelo-Finnish Republic from 1940 to 1944. During World War II, Andropov took part in partisan guerrilla activities. After the war, he moved to Moscow in 1951 and joined the party secretariat.

Rise to power

Following Stalin's death in March 1953, Andropov was demoted and "exiled" to the Soviet Embassy in Budapest by Georgy Malenkov. He played an important role in the Soviet invasion of Hungary in 1956.

Andropov returned to Moscow to head the Department for Liaison with Socialist Countries (1957-1967) and was promoted to the Central Committee Secretariat in 1962, succeeding Mikhail Suslov, and in 1967 he was appointed head of the KGB. In 1973 Andropov became a full member of the Politburo, although he did not resign as head of the KGB until 1982.

A few days after Brezhnev's death (November 10, 1982), Andropov was the surprise appointment to General Secretary over Konstantin Chernenko. He was the first head of the KGB to become General Secretary. He quickly added the posts of President of the USSR and chairman of the Defence Council. His appointment was received in the West with apprehension, in view of his roles in the KGB and in Hungary.

In 1978, as head of intelligence, Andropov called his station chief in Warsaw when Pope John Paul II was elected, asking how he had allowed such a thing to happen. On his question being deflected, he ordered the First Chief Directorate of the KGB to analyze the situation, with particular attention to determining if a German-American conspiracy was at work. He supposed that President Carter's national security adviser, Zbigniew Brzezinski, was a leader of a conspiracy to undermine Communism in Poland by selecting a Pole as Pope. (Ref: The New Yorker, April 11, 2005, p. 21.)

Andropov in office

During his rule, Andropov made attempts to improve the economy and reduce corruption. He was also remembered for his anti-alcohol campaign and struggle for enhancement of work discipline. Both campaigns were carried out by a typically Soviet administrative approach and harshness vaguely reminiscent of Stalin's rule.

In foreign policy he achieved little the war continued in Afghanistan. Andropov's rule was also marked by the deterioration of relations with the United States. While he launched a series of proposals that included a reduction of intermediate-range nuclear missiles in Europe and a summit with U.S. President Ronald Reagan, these proposals fell on the deaf ears of the Reagan and Thatcher administrations. Cold War tensions were exacerbated by the downing by Soviet fighters of a civilian jet liner that strayed over the USSR on September 1, 1983 and the United States deploying Pershing missiles in Europe in response to the Soviet SS-20. Soviet-U.S. arms control talks on intermediate-range nuclear weapons in Europe were suspended by the Soviet Union in November 1983.

One of his most famous acts during his short time as leader of the Soviet Union was responding to a letter from an American child named Samantha Smith and inviting her to the Soviet Union, which resulted in Smith becoming a well-known peace activist.

Andropov's legacy

Andropov died of kidney failure on February 9, 1984, after several months of failing health, and was succeeded by Konstantin Chernenko.

Andropov's legacy remains the subject of much debate within Russia and elsewhere, both amongst scholars and in the popular media. He remains the constant focus of television documentaries and popular non-fiction, particularly around important anniversaries.

Despite his hard-line stance in Hungary and the numerous banishments and intrigues for which he was responsible during his long tenure as head of the KGB, he has become widely regarded by many commentators as a humane reformer; they cite evidence that he promoted Mikhail Gorbachev through the ranks of the party and was regarded by many as comparatively tolerant as a KGB chief. He was certainly generally regarded as inclined to more gradual reform than was Gorbachev; the bulk of the speculation centres around whether Andropov would have reformed the USSR in a manner which did not result in its eventual destruction.

The short time he spent as leader, much of it in a state of extreme frailty, leaves debaters few concrete indications as to the nature of any hypothetical extended rule. As with the shortened rule of Lenin, speculators are left much room to advocate favourite theories and to develop the minor cult of personality which has formed around him.

| Preceded by: Leonid Brezhnev | General Secretary of the Soviet Communist Party 1982–1984 | Succeeded by: Konstantin Chernenko Further reading

it:Yuri Andropov nl:Joeri Andropov id:Yuri Andropov ja:ユーリ・アンドロポフ no:Jurij Andropov pl:Jurij Andropow pt:Yuri Andropov ro:Iuri Andropov ru:Андропов, Юрий Владимирович fi:Juri Andropov sv:Jurij Andropov zh-cn:尤里·安德罗波夫 |