Odin

|

|

Template:Dablink Odin, Icelandic/Old Norse Óðinn, Swedish Oden, English/Anglo-Saxon and Old Saxon Wõden, Old Franconian Wodan, Alemannic Wuodan, German Wotan or Wothan Lombardic Godan. Although its precise mythological meaning is controversial, the name appears to be formed from òð and -in. In Old Norse, òð means by itself '"wit, soul" and in compounds "fierce power, energy;" the suffix -in means "master, lord." Thus, Odin means master of the life force.

Odin is considered to be the supreme god of late Germanic and Norse mythology. His role, like many of the Norse pantheon, is complex: he is god of both wisdom and war. He is also attributed as being a god of magic, poetry, victory, and the hunt.

| Contents |

General characteristics

For the Norsemen, his name was synonymous with battle and warfare, for he appears throughout the myths as the bringer of victory.

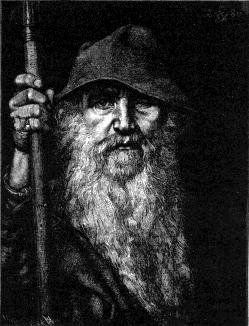

Odin was a shape-changer, able to change his skin and form in any way he liked. He was said to travel the world disguised as an old man with a staff, one-eyed, grey-bearded and wearing a wide-brimmed hat.

Odin is deeply associated with the concept of the Wild Hunt, a noisy, bellowing movement across the sky, leading a host of the slain, directly comparable to Vedic Rudra. Odin and Frigg participated in this together.

Receiver of the Dead

Snorri Sturluson's Edda depicts Odin as welcoming the great dead warriors who have fallen in battle into his hall, Valhalla. These fallen, the einherjar, are assembled by Odin to support the gods in the final battle of the end of the world, Ragnarök.In the Norse sagas, Odin often acts as the instigator of wars, sending his valkyries to influence the battle in his desired directions, and to select the dead. This in order to gather the best warriors in Valhalla.

Sometimes Odin himself even appears in person. In one version of the end of the Battle of Bråvalla, Odin himself arrives to fetch the aged King Harald Hildetand. When Helgi Hundingsbane has distinguished himself enough in battle and his brother-in-law Dag feels the need to avenge his father (whom Helgi had killed), Odin lends Dag his spear. Arrived in Valhalla, Helgi immediately gets perks as one of the foremost warriors.

Odin and Mercury

Less is known about the role of Odin as receiver of the dead among the more southern Germanic tribes. The Roman historian Tacitus probably refers to Odin when he talks of Mercury. The reason is that, like Mercury, Odin was regarded as Psychopompos, "the leader of souls".

Caesar calls Mercury the "deum maxime" of the Germans in De Bello Gallico 6.17.1.

Paulus Diaconus (or Paul the Deacon) writing in the late 8th century, tells that Odin (Guodan) was the chief god of the Langobards and like earlier southern sources he identifies Odin with Mercury (History of the Langobards,, I:9). Because of this identification, Paulus adds that the god Guodan "although held to exist [by Germanic peoples], it was not around this time, but long ago, and not in Germania, but in Greece" where the god originated. Robert Wace also identifies Wotan with Mercury. Viktor Rydberg, in his work on Teutonic Mythology, draws a number of other parallels between Odin and Mercury, such as the fact that they were both responsible for bringing poetry to mortal man.

Etymology

Old Norse Óðinn goes back to an earlier *Wōðinaz, consistent with the initial consonant of the West Germanic form of the name. Adam von Bremen etymologizes the god worshipped by the 11th century Scandinavian pagans as "Wodan id est furor" ("Wodan, which means 'ire'."), a possibility still commonly assumed today, connecting the name with Old English wōd, Gothic wōds, Old Norse *óðr (see Odr), Old High German wuot, all meaning "possessed, insane, raging".

The common Proto-Germanic form is *Wodinaz, which may go back to a pre-Proto-Germanic *Vatinos. It has been noted, however, that the Anglo-Saxon Woden is not in exact correspondence with German Wotan, suggesting that the latter has been transformed by popular etymology to conform with the meaning "the raging one", particularly after Christianisation, when Wotan was seen as a demon, while the Nordic and the Anglo-Saxon forms preserved the original form of the name. One possibility is that the name was borrowed from the Celts, roughly at the time of Tacitus when Germanic and Celtic tribes were in close contact on either side of the Rhine, and is associated with the Celtic priestly caste of the Vates. The Celtic word is ultimately derived from the same root (possibly Proto-Indo-European, but only attested in Celtic and Germanic) as the Germanic words for "possessed" cited above, *vāt-, with a more general meaning of "spiritually excited", also preserved in the Irish word for "poet", fáith. If the word is indeed a loan from the Celtic, it may be an important hint to the dating of the Proto-Germanic Sound changes.

Eddaic Odin

According to the Edda, Odin was a son of Bestla and Bor and brother of Vé and Vili and together with these brothers he cast down the frost giant Ymir and created the world from Ymir's body. The three brothers are often mentioned together. "Wille" is the German word for "will" (English), "Weh" is the German word (Gothic wai) for "woe" (English: great sorrow, grief, misery) but is more likely related to the archaic German "Wei" meaning 'sacred'.

Odin fathered his most famous son Thor on Jord 'Earth'. But his wife and consort was the goddess Frigg who in the best-known tradition was the loving mother of their son Baldr). By the giantess Gríðr, Odin was the father of Víðarr and by Rind he was father of Vali. Also many royal families claimed descent from Odin through other sons. For traditions about Odin's offspring see Sons of Odin.

Attributes

Ardre_Odin_Sleipnir.jpg

Attributes of Odin are Sleipnir, an eight-legged horse, and the severed head of Mímir, which foretold the future. He employed Valkyrjur to gather the souls of warriors fallen in battle (the Einherjar), as these would be needed to fight for him in the battle of Ragnarok. They took the souls of the warriors to Valhalla (the hall of the fallen), Odin's residence in Asgard. One of the Valkyries, Brynhildr, was imprisoned in a ring of fire by Odin for daring to disobey him. She was rescued by Sigurd. He was similarly harsh on Hodur, a blind god who had accidentally killed his brother, Baldur. Odin and Rind, a giantess, raised a child named Váli for the specific purpose of killing Hod.

Odin has a number of magical artifacts associated with him: the dwarven spear Gungnir, which never misses its target, a magical gold ring (Draupnir), from which every ninth night eight new rings appear, an eight-legged horse (Sleipnir) and two ravens Huginn and Muninn (Thought and Memory) who travel the world to acquire information at his behest. He also commands a pair of wolves named Geri and Freki, to whom he gives his food for he himself consumes nothing but wine. From his throne, Hlidskjalf (located in Valaskjalf), Óðinn could see everything that occurred in the universe.

The Valknut is a symbol associated with Odin.

Names

The Norsemen gave Odin many nicknames; this was in the Norse skaldic tradition of kennings, a poetic method of indirect reference, as in a riddle. See List of names of Odin. The name Alföðr ("Allfather", "father of all") appears in Snorri Sturluson's Younger Edda. It probably refers to the Christian God in that book, but it may have referred to Odin at an earlier date. (It probably originally denoted Tiwaz, as it fits the pattern of referring to Sky Fathers as "father".)

Anglo-Saxon Woden

The Anglo-Saxon tribes brought Woden to England around the 5th and 6th centuries, continuing his worship until conversion to Christianity in the 8th and 9th centuries. Woden is the carrier-off of the dead, but not necessarily with the attributes of Norse Odin. Woden is also the leader of the Wild Hunt. The familial relationships are the same between Woden and the other Anglo-saxon gods as they are for the Norse.

According to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle and the Historia Britonum, Woden had the sons Wecta, Baeldaeg, Casere and Wihtlaeg.

- Wecta's line is continued by Witta, Wihtgils, Hengest and Horsa, and the Kings of Kent.

- Baeldaeg's line is continued by Brona, Frithugar, Freawine, Wig, Gewis, Esla, Elesa, Cerdic and the Kings of Wessex.

- Casere's line is continued by Tytmon, Trygils, Hrothmund, Hryp, Wilhelm, Wehha, Wuffa and the Kings of East Anglia.

- Wihtlaeg's line is continued by Wermund king of Angel, Offa, Angeltheow, Eomer, Icel and the Kings of Mercia.

Anglo-Saxon literature starts at about the time of the conversion from the old religion. Although whatever stories recording his part in the lives of men and the gods are lost, Woden's name survived in many settlement names and geographical features.

- Wansdyke - Woden's embankment

- Grimsdyke - From Grim, "hooded" a description of his appearance

- Wednesbury - Woden's burgh

Wednesday ('Wodens daeg') is named for him, his link with the dead making him the appropriate match to the Roman Mercury. (Compare with the French 'mercredi' for Wednesday)

Worship

Details of Migration period Germanic religion are sketchy, reconstructed from artefacts, sparse contemporary sources, and later the later testimonies of medieval legends and placenames. According to Jonas Bobiensis, the 6th century Irish missionary Saint Columbanus is reputed to have disrupted a Beer sacrifice to Wuodan (Deo suo Vodano nomine) in Bregenz. Wuodan was the chief god of the Alamanni, his name appears in the runic inscription on the Nordendorf fibula.

Pagan worship disappeared with Christianization, from the 8th century in England and Germany, lingering until the 12th or 13th century in Iceland and Scandinavia. Remnants of worship were continued into modern times as folklore.

Many places are named after Odin, especially in Scandinavia, such as Odense (Denmark) and Odensbacken (Sweden), but also places in other Germanic countries, such as Wednesbury (England), Wodensberg and Odenheim (Germany), and Woensdrecht (Netherlands). Almost all German Gaue (Latin, pagi) had mountains and other places named after him under such generic names as Wodenesberg, Wuodenesberg, Godesberg and Gudensberg, Wodensholt, etc.

Sacrifices

Odin was the only god in Scandinavian mythology to demand human sacrifice at the Blóts. Adam of Bremen relates that every ninth year, people assembled from all over Sweden to sacrifice at the Temple at Uppsala. Male slaves, and males of each species were sacrificed and hung from the branches of the trees. The practice of sacrifice is one reason why Thor was much more popular among the commonfolk. Committing suicide was also considered to be a shortcut to Valhalla.

As the Swedes had the right not only to elect king but also to depose a king, the sagas relate that both king Domalde and king Olof Trätälja were sacrificed to Odin after years of famine. See also sacred king.

It was common, particularly among the Cimbri, to sacrifice a prisoner to Odin prior to or after a battle. One such prisoner, the "Tollund Man", was discovered hanged, naked along with many others, some of whom were wounded, in Central Jutland. The victim singled out for such a sacrifice was usually the first prisoner captured in battle. The rites particular to Odin were sacrifice by hanging, as in the case of Tollund Man; impalement upon a spear, and burning. The Orkneyinga saga relates another (and uncommon) form of Odinic sacrifice, wherein the captured Ella is slaughtered by the carving out of a "blood eagle" upon his back.

More significantly, however, it has been argued that the killing of a combatant in battle was to give a sacrificial offering to Odin. The fickleness of Odin in battle was well-documented, and in Lokasenna, Loki taunts Odin for his inconsistency.

Sometimes sacrifices were made to Odin to bring about changes in circumstance, a notable example being the sacrifice of King Víkar (detailed in Gautrek's Saga and Saxo). Sailors in a fleet being blown off course drew lots to sacrifice to Odin that he might abate the winds; the king himself drew the lot and was hanged.

Sacrifices were probably also made to Odin at the beginning of summer, since Ynglinga saga states one of the great festivities of the calendar is at sumri, þat var sigrblót "in summer, for victory"; Odin is consistently referred to throughout the Norse mythos as the bringer of victory.

The Ynglinga saga also details the sacrifices made by the Swedish king Aun, who, it was revealed to him, would lengthen his life by sacrificing one of his sons every ten years; nine of his ten sons died this way. When he was about to sacrifice his last son Egil, the Swedes stopped him.

Shamanic traits

The goddess Freya is seen as an adept of the mysteries of seid (shamanism), a völva, and it is said that it was she who initiated Odin into its mysteries. In Lokasenna Loki abuses Odin for practising seid, condemning it as a unmanly art. A justification for this may be found in the Ynglinga saga where Snorri opines that following the practice of seid, the practitioner was rendered weak and helpless. Another explanation is that its manipulative aspects ran counter to the male ideal of forthright, open behaviour.

Odin was a compulsive seeker of wisdom, consumed by his passion for knowledge, to the extent that he sacrificed one of his eyes (which one this was is unclear) to Mimir, in exchange for a drink from the waters of wisdom in Mimir's well.

Some German sacred formulae, known as "Merseburger Zaubersprueche" were written down in c 800 AD and survived. One (this is the second) describes Wodan in the role of a healer:

- Phol ende UUodan vuorun zi holza.

- du uuart demo Balderes volon sin vuoz birenkit

- thu biguel en Sinthgunt, Sunna era suister;

- thu biguol en Friia, Volla era suister

- thu biguol en Uuodan, so he uuola conda

- sose benrenki, sose bluotrenki

- sose lidirenki: ben zi bena

- bluot zi bluoda, lid zi geliden

- sôse gelîmida sin!

English translation:

- Phol (Balder) and Wodan were riding in the forest

- Balder's foal dislocated its foot

- Sinthgunt and Sol, her sister, tried to cure it by magic

- Frige and Fulla, her sister, tried to cure it by magic

- it was charmed by Wodan, like he well could:

- be it bonesprain, be it bloodsprain

- be it limbsprain, bone to bones

- blood to blood, limb to limbs

- like they are glued!

Further, the creation of the runes, the Norse alphabet that was also used for divination, is attributed to Odin and is described in the Rúnatal, a section of the Havamal. He hanged himself from the tree Yggdrasil, whilst pierced by his own spear, to acquire knowledge. He remained thus for nine days and nights, a number deeply significant in Norse magical practice (there were, for example, nine realms of existence), thereby learning nine (later eighteen) magical songs and eighteen magical runes. The purpose of this strange ritual, a god sacrificing himself to himself because there was nothing higher to sacrifice to, was to obtain mystical insight through mortification of the flesh; however, some scholars assert that the Norse believed that insight into the runes could only be truly attained in death.

Some scholars see this scene as influenced by the story of Christ's crucifixion; and others note the similarity to the story of Buddha's enlightenment. it is in any case also influenced by shamanism, where the symbolic climbing of a "world tree" by the shaman in search of mystic knowledge is a common religious pattern. We know that sacrifices, human or otherwise, to the gods were commonly hung in or from trees, often transfixed by spears. (See also: Peijainen) Additionally, one of Odin's names is Ygg, and the norse name for the World Ash —Yggdrasil—therefore means "Ygg's (Odin's)horse". Another of Odin's names is Hangatyr, the god of the hanged.

Odin's love for wisdom can also be seen in his work as a farmhand for a summer, for Baugi, in order to obtain the mead of poetry. See Fjalar and Galar for more details.

Odin and Jesus

The 13th century eddaic account of Odin likely contains Christian elements. The scene where Odin hangs from a tree as a sacrifice to himself has been suggested to reflect the crucifixion of Jesus, down to the detail of having his side pierced with a spear. Odin's son Balder shares some of Jesus' traits as a youthful "dying and rising" god, but unlike in the case of latter, his resurrection fails and he has to remain in the underworld. The Havamal account of Odin's sacrifice positions Odin in the otherwise unique Pauline Christian attributes of a "father god" who suffers and defeats death.

The historical similarity of Odin and Jesus was rediscovered by Richard Wagner. Wagner's association of Odin with Jesus is treated in the Notes of the Seminar Given in 1928–1930 of Carl Gustav Jung. Recently, the German NPD issued T-Shirts labelled Odin statt Jesus ("Odin rather than Jesus") that were popular also among apolitical Neo-Pagans, reviving the Nazi idea of Odin as an "Aryan Jesus".

Medieval reception

As the chief god of the Germanic pantheon, Odin received particular attention from the early missionaries. For example, his day is the only day to have been renamed in the German language from "Woden's day", still extant in English Wednesday to the neutral Mittwoch ("mid-week"), while other gods were not deemed important enough for propaganda (Tuesday "Tyr's day" and Friday "Freyja's day" remained intact in all Germanic languages). For many Germans, St. Michael replaced Wotan, and many mountain chapels dedicated to St. Michael can be found, but Wotan also remained present as a sort of demon leading the Wild hunt of the host of the dead, e.g. in Swiss folklore as Wuotis Heer.

In England, Woden was not so much demonized as rationalized, and in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, he appears as a perfectly earthly king, only four generations removed from Hengest and Horsa.

Snorri Sturluson's record of the Edda is striking evidence of the climate of religious tolerance in medieval Iceland, but even he feels compelled to give a rational account of the Aesir in his preface. In this scenario, Snorri speculates that Odin and his peers were originally refugees from Troy, etymologizing Aesir as derived from Asia. Some scholars believe that Snorri's version of Norse mythology is an attempt to mould a more shamanistic tradition into a Greek mythological cast. In any case, Snorri's writing (particularly in Heimskringla) tries to maintain an essentially scholastic neutrality. That Snorri was correct was one of the last of Thor Heyerdahl's archeo-anthropological theories (see The search for Odin).

In many Germanic languages, the name for the fourth day of the week (if one counts from Sunday) is frequently, "Wotan's Day" or "Woden's Day", (Wednesday in English, compare Norwegian, Danish and Swedish onsdag, Dutch woensdag; curiously the equivalent day in German is simply "mid-week" (Mittwoch)). This is thought to translate the Latin Dies Mercurii, "Mercury-day" (cf. French mercredi), owing primarily to Tacitus' linking of the two gods.

Last battle decided by Odin

The spread of Christianity was slow in Scandinavia, and it worked its way downwards from the nobility. Among common people, beliefs in Odin would linger for centuries, and legends would be told until modern times.

The last battle where Scandinavians attributed a victory to Odin was the Battle of Lena in 1208 [1] (http://runeberg.org/img/sverhist/1/0325.5.png). The former Swedish king Sverker had arrived with a large Danish army, and the Swedes discovered that the Danish army was more than twice the size of their own. Naturally, the Danes got the upper hand and they should have won. However, the Swedes claimed that they suddenly saw Odin riding on Sleipnir. Accounts vary on how Odin gave the Swedes victory, but in one version, he rode in front of their battle formation.

The Norwegians long told a legend about a one-eyed rider with a broad-brimmed hat and a blue coat who had asked a smith to shoe his horse. The suspicious smith asked where the stranger had stayed during the previous night. The stranger mentioned so distant places that the smith would not believe him. The stranger said that he had stayed for a long time in the north and taken part in many battles, and this time he was going to Sweden. When the horse was shod, the rider mounted his horse and said "I am Odin" to the stunned smith, rode up in the air and disappeared. The next day, the battle of Lena took place.

Modern age

With the Romantic Viking revival of the early-to-mid 19th century, Odin's popularity increased again. Wotan is a principle character in Richard Wagner's Der Ring des Nibelungen, written between 1848 and 1874. Odin is worshipped by Germanic reconstructivist Neo-Pagan groups (see Odinic Rite, Odinism).

As the master of the life force, óð, his name provides the root for Od, the hypothetical vital energy that permeates all living things and binds them together.

Odin is frequently referred to in popular culture, see References to Odin in popular culture and Odin (disambiguation).

Literature

- The Cult of Othinn - (Hector Chadwick)

- The Battle God of the Vikings - (H. R. E. Davidson York 1972)

- The Lost Gods of England, Brian Branston

- In search of the Dark Ages, Michael Wood

- "Wotan" - (Carl Jung)

- Final Fantasy series - a summonned beast with the attack "Zantetsuken" (Iron-Cutting Sword).

- A name of which that appears on World of Warcraft, on the Blackhand server.

Template:NorseMythology Template:Mythological king of Swedenang:Wóden ca:Odín da:Odin de:Odin es:Odín eo:Odino fr:Odin it:Odino nl:Odin ja:オーディン nb:Odin nn:Odin pl:Odyn pt:Odin ro:Odin fi:Odin sv:Oden uk:Одін zh:奥丁