Old European Script

|

|

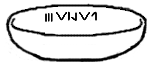

The Old European Script (also known as the Vinča alphabet, Vinča script or Vinča-Tordos script) is a name sometimes given to the markings on prehistoric artefacts found in south-eastern Europe. Some believe the markings to be a writing system of the Vinča culture, which inhabited the region around 6000-4000 BC. Others doubt that the markings represent writing at all, citing the brevity of the purported inscriptions and the dearth of repeated symbols in the purported script.

| Contents |

The discovery of the script

In 1875, archaeological excavations led by the archeologist Zsofia Torma (1840 - 1899) at Turdaş (Tordos), near Orăştie in Transylvania (now Romania) unearthed a cache of objects inscribed with previously unknown symbols. A similar cache was found during excavations conducted in 1908 in Vinča, a suburb of the Serbian city of Belgrade, some 120km from Tordos. Later, more such fragments were found in Banjica, another part of Belgrade. Thus the culture represented is called the Vinca-Tordos culture, and the script often called the Vinca-Tordos script. To date, more than a thousand fragments with similar inscriptions have been found on various archaeological sites throughout south-eastern Europe, notably in Greece, Bulgaria, Romania, eastern Hungary, Moldova, southern Ukraine and other locations in the former Yugoslavia.

Most of the inscriptions are on pottery, with the remainder appearing on whorls (flat cylindrical annuli), figurines, and a small collection of other objects. Over 85% of the inscriptions consist of a single symbol. The symbols themselves consist of a variety of abstract and representative pictograms, including zoomorphic (animal-like) representations, combs or brush patterns and abstract symbols such as swastikas, crosses and chevrons. Other objects include groups of symbols, of which some are arranged in no particularly obvious pattern, with the result that neither the order nor the direction of the signs in these groups is readily determinable. The usage of symbols varies significantly between objects: symbols that appear by themselves tend almost exclusively to appear on pots, while symbols that are grouped with other symbols tend to appear on whorls.

The importance of these findings lies in the fact that the oldest of them are dated around 4000 BC, around a thousand years before the proto-Sumerian pictographic script from Uruk (modern Iraq), which is usually considered as the oldest known script. Analyses of the symbols showed that they had little similarity with Near Eastern writing, leading to the view that they probably arose independently of the Sumerian civilization. There are some similarities between the symbols and other Neolithic symbologies found elsewhere, as far afield as Egypt, Crete and even China. However, Chinese scholars have suggested that such signs were produced by a convergent development of what might be called a precursor to writing which evolved independently in a number of societies.

Although a large number of symbols are known, most artefacts contain so few symbols that they are very unlikely to represent a complete text. Possibly the only exception is a stone found near Sitovo in Bulgaria, the dating of which is disputed; regardless, the stone has only around 50 symbols. It is unknown which language used the symbols, or indeed whether they stand for a language in the first place.

Meaning of the symbols

The nature and purpose of the symbols is still something of a mystery. It is not even clear whether or not they constitute a writing system. If they do, it is not known whether they represent an alphabet, syllabary, ideograms or some other form of writing. Although attempts have been made to decipher the symbols, there is no generally accepted translation or agreement as to what they mean.

At first it was thought that the symbols were simply used as property marks, with no more meaning than "this belongs to X"; a prominent holder of this view is archaeologist P. Biehl. This theory is now mostly abandoned as same symbols have been repeatedly found on the whole territory of Vinča culture, on locations hundreds of kilometers and years away of each other.

The prevailing theory is that the symbols were used for religious purposes in a traditional agricultural society. If so, the fact that the same symbols were used for centuries with little change suggests that the ritual meaning and culture represented by the symbols likewise remained constant for a very long time, with no need for further development. The use of the symbols appear to have been abandoned (along with the objects on which they appear) at the start of the Bronze Age, suggesting that the new technology brought with it significant changes in social organization and beliefs.

One argument in favour of the ritual explanation is that the objects on which the symbols appear do not appear to have had much long-term significance to their owners - they are commonly found in pits and other refuse areas. Certain objects, principally figurines, are most usually found buried under houses. This is consistent with the supposition that they were prepared for household religious ceremonies in which the signs incised on the objects represent expressions: a desire, request, vow or whatever. After the ceremony was completed, the object would either have no further significance (hence would be disposed of) or would be buried ritually (which some have interpreted as votive offerings).

Some of the "comb" or "brush" symbols, which collectively comprise as much as a sixth of all the symbols so far discovered, may represent numbers. Some scholars have pointed out that over a quarter of the inscriptions are located on the bottom of a pot, an ostensibly unlikely place for a religious inscription. The Vinča culture appears to have traded its wares quite widely with other cultures (as demonstrated by the widespread distribution of inscribed pots), so it is possible that the "numerical" symbols conveyed information about the value of the pots or their contents. Other cultures, such as the Minoans and Sumerians, used their scripts primarily as accounting tools; the Vinča symbols may have served a similar purpose.

Other symbols (principally those restricted to the base of pots) are wholly unique. Such signs may denote the contents, provenance/destination or manufacturer/owner of the pot.

Controversial issues

The Vinča markings have not attracted as much linguistic attention as recognized but undeciphered scripts such as Crete's Linear A and Easter Island's Rongorongo. However, the Vinča material has still managed to stir some controversies of its own.

The primary advocate of the idea that the markings represent writing, and the person who coined the name "Old European Script", was Marija Gimbutas (1921-1994), an important 20th century archaeologist and premier advocate of the notion that the Kurgan culture of Central Asia was an early Indo-European culture. Later in life she turned her attention to the reconstruction of a hypothetical pre-Indo-European Old European culture, which she thought spanned most of Europe. She observed that neolithic European iconography was predominately female — a trend also visible in the inscribed figurines of the Vinča culture — and concluded the existence of a matristic (not matriarchal) culture that worshipped range of goddesses and gods. (Gimbutas did not posit a single universal Mother Goddess.) She also incorporated the Vinča markings into her model of Old Europe, suggesting that they might either be the writing system for an Old European language, or, more probably, a kind of "pre-writing" symbolic system. Most archaeologists and linguists disagree with Gimbutas' interpretation of the Vinča signs as a script: it is all but universally accepted among scholars that the Sumerian cuneiform script is in fact the earliest form of writing.

A rather odder controversy concerns the theories of Dr. Radivoje Pešić from Belgrade. In his book The Vinča Alphabet, he proposes that all of the symbols exist in the Etruscan alphabet, and conversely, that all Etruscan letters are found among Vinča signs. However, these claims are not taken seriously by scholars, who demonstrate that the Etruscan alphabet is derived from the West Greek Alphabet, which in turn is derived from the Phoenician writing system. This is however not completely incompatible with Pešić's views as he claims that the Phoenician writing system descended from Vinčan. Pešić's critics have claimed that his support for the continuity theory, which claims a Slavic presence in the Balkans far earlier than the usually accepted date, is motivated by a nationalistic agenda; hence, for instance, his claim that the poet Homer must have spoken a Slavonic dialect (Pešić, 1989).

See also

References

- Pešić, Radivoje, The Vincha Script (ISBN 86-7540-006-3)

- Pešić, Radivoje, "On the Scent of Slavic Autochthony in the Balkans (http://pub37.ezboard.com/fistorijabalkanafrm28.showMessage?topicID=11.topic)," Macedonian Review 19, nos. 2-3 (1989), 115-116

- Gimbutas, Marija. 1974. The Gods and Goddesses of Old Europe 7000 - 3500 BC, Mythos, Legends and Cult Images

- Winn, Milton McChesney. 1973. The signs of the Vinča Culture : an internal analysis : their role, chronology and independence from Mesopotamia

- Winn, Shan M.M. 1981. Pre-writing in Southeastern Europe: the sign system of the Vinča culture, ca. 4000 BC

External links

- Vinca symbols (http://www.omniglot.com/writing/vinca.htm) at omniglot.com, including a font

- The Number System of the Old European Script - Eric Lewin Altschuler (http://arxiv.org/html/math.HO/0309157)

- The Old European Script: Further evidence - Shan M. M. Winn (http://www.prehistory.it/ftp/winn.htm)de:Vinča-Schrift